The most immutable fact they teach you in medical school is that anatomy is the absolute bedrock of surgery. As an eager young surgical intern, I often got doused in my patients’ vomit and shit. I tried to see the clinical bright side: Maybe the old man’s feces contained blood or the teen who had barfed up the offending Tylenol would avoid a liver transplant. Otherwise, the contents of normal guts were of less interest.

Back then, we were taught that the sole purpose of the gastrointestinal tract was to extract nutrients from food. What I didn’t expect, after practicing as a surgeon myself for over 20 years, is that what we think we know about human anatomy is actually changing all the time and that our bodies are more varied, more full of wonders and magical revelations, than we could ever have imagined.

The accompanying article is adapted from “Alive: Our Bodies and the Richness and Brevity of Existence,” by Gabriel Weston (David R. Godine, 287 pages).

It turns out the gut isn’t a simple tube after all, but the largest sensory organ we have, the most receptive interface that exists between a person and the outside world. With more immune cells than across the rest of the body put together, and an internal surface area a hundred times bigger than the skin, the gut is held within an elaborate harness we now call the gut-brain, which contains up to 600 million neurons. This plexus of nerves doesn’t just chivvy food along. It is like a delicate switchboard, continually integrating information about what we’ve eaten, our blood chemistry, our immune state, and our microbiology.

In 2004, a landmark study by the Japanese gastroenterologist Nobuyuki Sudo showed that mice raised with no gut flora have a disrupted stress response, which can be partly corrected by colonizing their intestines with normal bacteria. Since then, countless experiments have demonstrated that the brain, the gut, and its resident bacteria coexist in an intimate three-way circuit. With the vast majority of all gut research published in the last 20 years, we’re learning more every single day about the importance of these previously disregarded life forms, why it matters to have a diverse gut flora, and the numerous pathological consequences that may occur if this balance gets disrupted. And if you’re looking for a stark example, here it is.

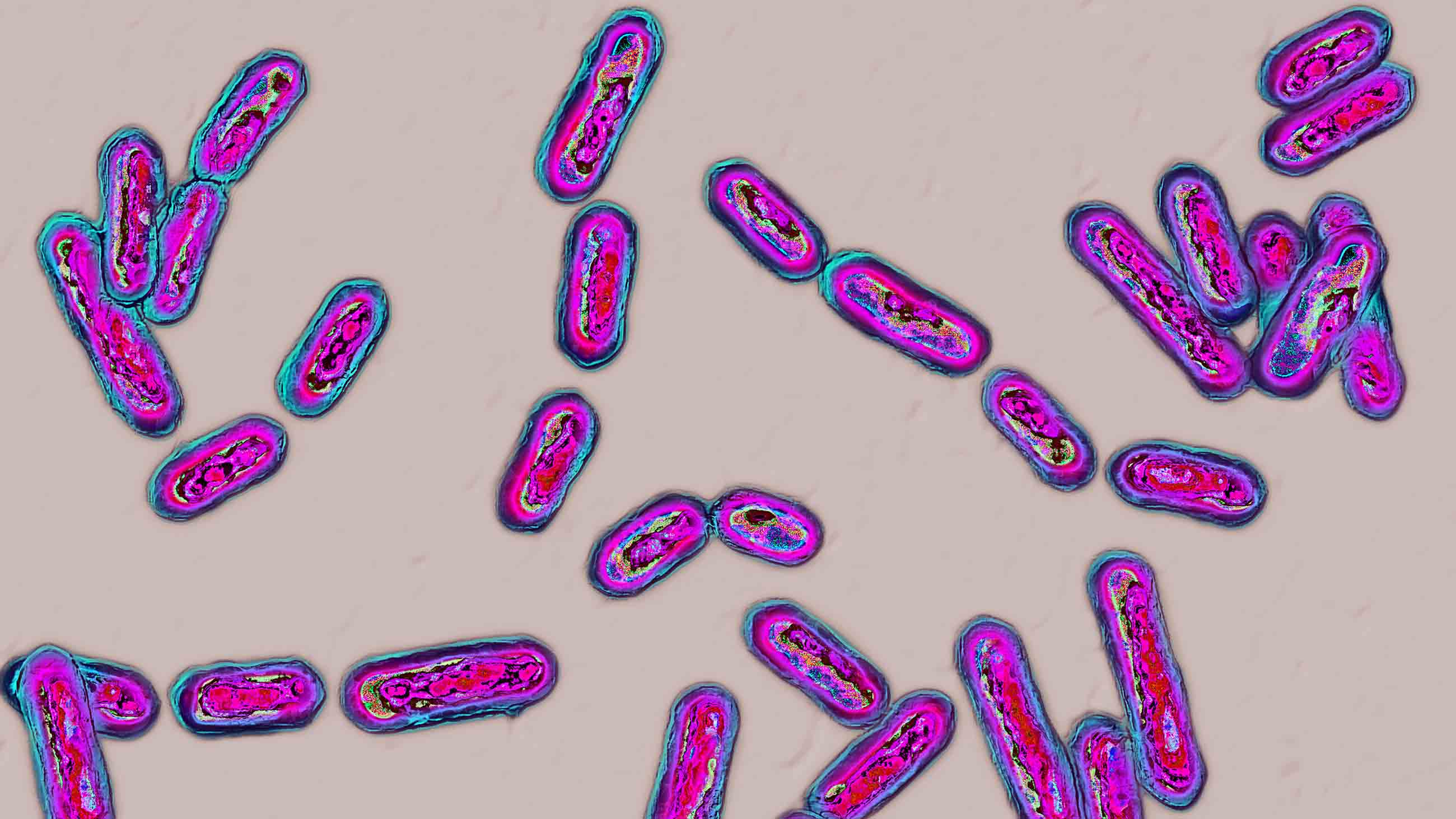

Clostridioides difficile is the leading cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea worldwide. Lucky patients might get away with a few days of diarrhea, nausea, abdominal cramping, and fever, but — in extreme cases — infection with this bug causes a widespread inflammatory condition called pseudomembranous colitis which can result in bowel perforation, sepsis, and death.

Accorded the highest level of threat by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, C. diff is a massive problem, infecting half a million and killing 30,000 in the U.S. alone every year. And although it used to be confined to frail old people in hospitals, the condition is now cropping up in the community among children, pregnant women, and other healthy adults.

Rampant in soil, water, and the intestinal tract, C. diff has two different guises: a spore for transmission and a vegetative form for destruction. Spores are the most resilient cellular form on the planet and can survive in a dormant state for decades. This one is built like a gobstopper, its arsenal encased in several different protective shells, inuring it to oxygen, extremes of temperature, alcohol, disinfectants, and radiation. The outermost layer even has little projections that are thought to help it stick to hospital bedding.

Clostridioides difficile is the leading cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea worldwide, infecting half a million and killing 30,000 in the U.S. alone every year.

Once swallowed, the dormant spore passes, unperturbed by the acid onslaught of the stomach, into the small intestine. In a healthy gut nothing happens. But, if its usual chemical environment is disrupted, the spore is able to germinate. Roused to its vegetative state, C. diff does two things. First, it configures itself into a mother cell and a forespore. The forespore is the baby and once it achieves what is known as phase-bright status, it splits off to form a new dormant bug. The remaining vegetative bacterium is now free to unleash itself, discharging powerful toxins which penetrate the target cells of the large intestine, and turn our guts to pulp.

When I was at medical school, we students loved to characterize bacteria as villains, the better to revel in how to thrash them with antibiotics. Lately, though, C. Diff has become a virtuoso at resisting treatment. As our pharmacological prowess has waned, we’ve had to confront a paradox, which is that while some individuals suffer debilitating symptoms, 1 in 10 of us are able to host it in our gut with absolutely no ill effects.

What really determines a patient’s outcome is the background environment of their gut. The precise chemical milieu that renders some patients vulnerable is almost always the result of having been treated for another infection with antibiotics. Yes, it’s that crazy. The gold-standard therapy for C. diff is the selfsame class of drugs that causes the condition in the first place.

Powerful modern informatics have revealed a hidden universe of hundreds of trillions of viruses, fungi, yeasts, and bacteria which make our bodies their home, 99 percent of which reside in the gut. Research has also showed us what they do. Bacteria extract nutritional goodies, especially in times of food scarcity. They break down fiber into short-chain fatty acids, which regulate sugar metabolism and appetite. They make vitamins by a process of fermentation.

But they operate well beyond the gut’s traditional remit of digestion and absorption. Gut bacteria actually keep us healthy. In the case of C. diff, simply having a gut with a rich array of different species keeps the microbe in balance with its neighbors, and stops it taking over and causing disease.

You’d think these headlines about the importance of gut diversity must be hot off the press. But it isn’t so. As far back as 1886, Austrian pediatrician Theodor Escherich described the rich variety of infant gut bacteria, including their role in the decomposition of food. Just before the turn of the 20th century, Henry Tissier successfully treated a group of children suffering from gastrointestinal disease with a concoction of bacteria taken from healthy breastfeeding babies. During the First World War, microbiologist Alfred Nissle developed and patented gelatine capsules which contained a particular strain of E. coli as a treatment for dysentery in soldiers.

It’s not as if we’ve been living in complete ignorance about C. diff either. First isolated in 1893 by an American surgeon called John Finney, a few decades later it was declared to be a completely normal part of the infant gut flora by Ivan Hall and Elizabeth O’Toole. In the mid-1970s, John Bartlett published a study which demonstrated antibiotics could provoke C. diff in hamsters and, by the end of the decade, two further papers had proved a causal link between antibiotics and C. diff-associated pseudomembranous colitis in humans.

Nosocomial is the term for an illness a patient contracts while in hospital. Iatrogenic describes a disease that’s unwittingly caused by the interference of a doctor. We assume these events are unavoidable. So why are thousands of our patients are still dying annually of a condition we’re at least partly responsible for? It turns out I’m not the only one who’s baffled.

In a fresh, sunny operating theater in Providence, Rhode Island, I am waiting to meet Dr. K, one of the modern pioneers of a very different treatment for C. diff. Fecal microbiota transplant, or FMT, is indicated for those patients whose C. diff infections are either recurring or not responsive to standard treatment. The procedure involves transferring bacteria from healthy donor stool into a sick recipient’s intestine, the aim being to restore a diverse range of bacteria in their gut.

The double doors open and Dr. K walks in, all smiles and glossy hair, chatting to an elderly woman being wheeled by a couple of nurses. Once the hospital bed is fixed in position, we introduce ourselves and, as Dr. K checks her equipment, she tells me how she got started. (For privacy, I’m referring to this doctor by their last initial.)

A few years back, a young woman turned up at her clinic with an all-too-common history of months of suffering from diarrhea after taking antibiotics for a quite separate infection. But this was no usual patient. With a stack of evidence from the internet and a boyfriend in tow happy to be her donor, she cut straight to the chase. She wanted to be given a stool transplant. Initially taken aback — Dr. K wasn’t used to patients telling her what to do — this doctor performed the radical clinical courtesy of keeping an open mind, and promised to read the notes her patient had put together.

Multiple studies have shown fecal microbiota transplant to be about 90 percent effective, making it a highly successful treatment.

In a nutshell, this is what she learned. In the fourth century, a Chinese Daoist called Ge Hong administered fecal suspensions orally to patients who had diarrhea from food poisoning. In 1958, a surgeon called Ben Eiseman published an account of successfully treating pseudomembranous colitis with feces. And a gastroenterologist called Thomas Borody was currently using healthy donor stool to treat refractory cases of C. diff in Australia, with great outcomes.

Dr. K was bowled over. Despite cynicism from most of her colleagues, she went ahead and performed her first fecal transplant in 2008. And when the young woman’s symptoms disappeared completely after a single treatment, she decided to set up a service, making the therapy available to others and gathering data on all her results.

In 2013, she found herself in good company when a landmark randomized controlled trial in The New England Journal of Medicine declared FMT so much more effective than antibiotics at treating C. diff that researchers had to halt the study early, as it felt unethical to withhold the new treatment from the control group. Multiple subsequent studies showed it to be about 90 percent effective, making it a highly successful treatment.

With her patient curled up on one side, Dr. K introduces the narrow scope, and pink colonic mucosa blooms into view on the screen in front of us. A nurse dressed in lemon yellow holds out a plastic jug, in which five 60-milliliter syringes stand, pretty as stems in a vase, full of strained and saline-diluted donor stool. As she empties the unlikely elixir into her patient’s sigmoid colon, she tells me how skeptical colleagues who once laughed her off now queue up for training.

The whole procedure is done within 10 minutes and, when I accompany Dr. K the following morning to check on the patient’s response, we find the previously frail lady euphoric. After just one treatment, her chronic diarrhea has completely resolved.

Later that day, I hop on a train to Boston to visit OpenBiome, the not-for-profit stool bank where Dr. K gets all her samples, set up in 2013 by a couple of MIT graduate students, after one of their friends recovered from chronic C. diff thanks to a DIY fecal transplant.

There’s a lot to marvel at — the energy of the co-founder who welcomes me in, smooth-chinned as a schoolboy, the giant fridges, in which thousands of square frosted bottles of donor feces are shelved in neat rows, the sheer rate of expansion of this start-up which, having initially occupied no more than a small corner of an MIT lab, has since become a full-scale operation having delivered more than 70,000 pre-screened, ready-to-use samples to a thousand clinical destinations.

Let’s not forget what we owe our patients. The barnyard whiff of fecal transplant and a fear of ridicule stood in the way of progress for generations.

The march to beat C. Diff continues apace. A potential mRNA vaccine against the bug has yielded promising results in mice. The FDA has recently approved two biotherapeutic preparations to overcome some of the unavoidable hazards of transplanting feces. Researchers are also busy exploring immune therapies and antibiotic neutralizers as an adjunct to current treatments.

But let’s not forget what we owe our patients. The barnyard whiff of fecal transplant and a fear of ridicule stood in the way of progress for generations. In the end, it has taken some brave individuals to look out for their own interests and persuade a few medics and entrepreneurs to take a punt with them.

Prepared to see potential where others were too prissy to look, this tenacious lot armed themselves with evidence and have succeeded in pushing a remarkable medical treatment right into the mainstream.

Gabriel Weston is the author of “Direct Red: A Surgeon’s Story,” which won the PEN Ackerley Prize, and a novel, “Dirty Work.” She is a medical presenter for the BBC, writes reviews for Lancet and The Telegraph, works as a part-time surgeon, and lives in London with her husband and four children.