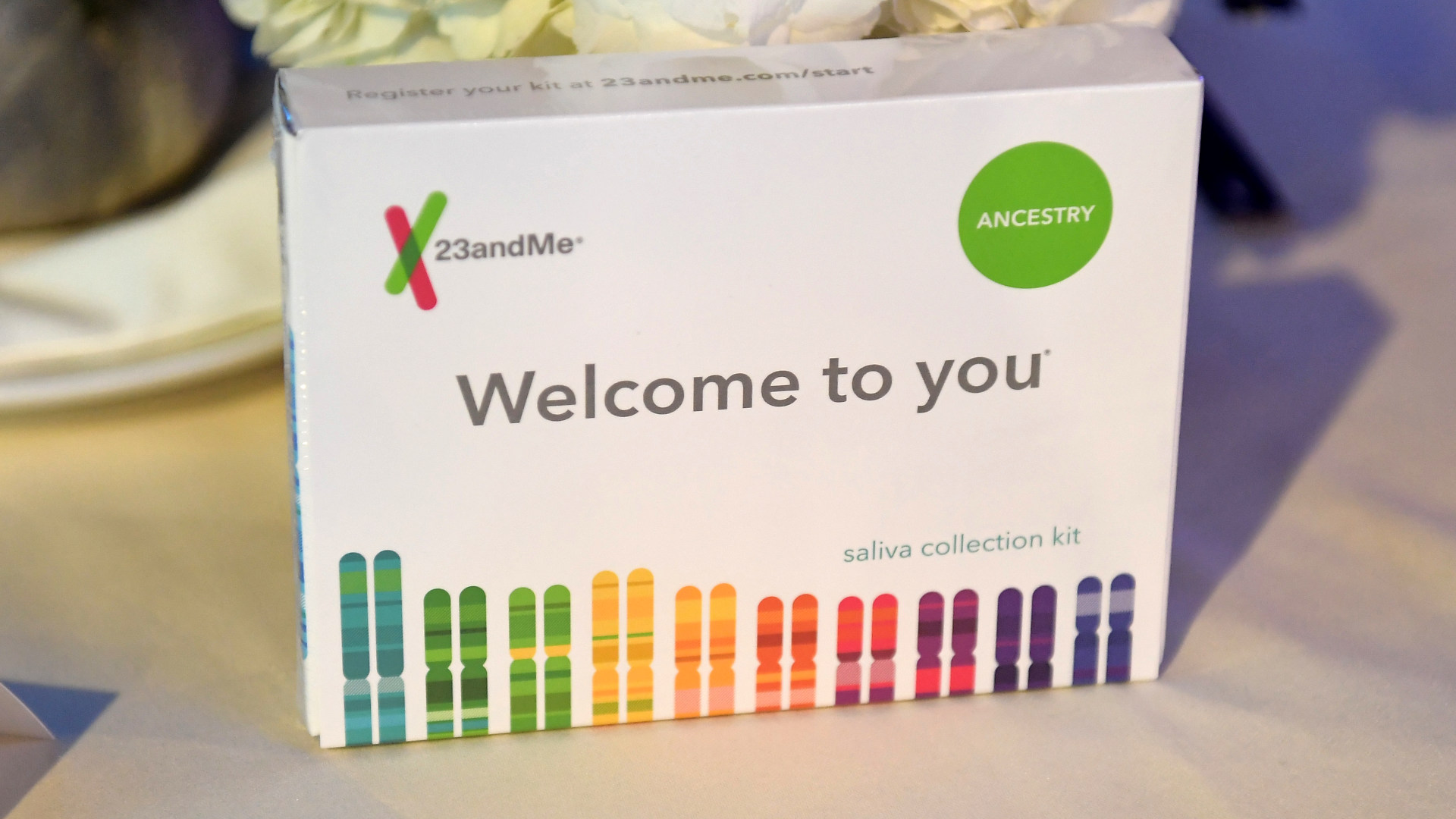

The announcement that 23andMe is filing for bankruptcy came as little surprise to many who had been following the company’s tumultuous year. CEO Ann Wojcicki was unable to rescue the genetic testing company from its unsustainable business model, leaving some 15 million consumers in limbo about the fate of their genetic data. Within a day, articles and online forums began advising customers to request the deletion of their data, warning of the possibilities of misuse that may ensue. Though 23andMe has always branded itself as a company dedicated to data protection, its own privacy statement makes it clear that customer data can be sold in the event of bankruptcy, merger, or acquisition, meaning a new entity may inherit the right to use (or profit from) 23andMe’s massive trove of genetic data.

While individuals should certainly take steps to safeguard their genetic information, this incident raises concern about the lack of restrictions over how a company uses customers’ genetic data in the first place. Many consumers mistakenly believe that such data is protected under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA. However, that legislation extends only to “covered entities and business associates,” which are mainly health care providers and organizations they contract with to deliver care. Companies not engaging in health care delivery are unlikely to be subject to HIPAA rules, raising concerns about what the entity that eventually acquires 23andMe may do with this data.

Even for covered entities, HIPAA does not provide absolute protection of health data, permitting providers to share data relatively freely, as long as it is de-identified — meaning it is stripped of information that could be used to link it back to a particular individual. HIPAA even allows them to sell de-identified data sets. The effect is that genomic data become economic assets — pieces of property that are mined and traded, not by the individuals they originate from but by corporations who turn them into profits. It’s undeniable that genomic data holds tremendous research potential, but commodifying it threatens to de-personalize something intrinsic and core to our identities. Our genetic sequence, after all, is unlike any other type of data. Barring identical twins, each of our genomes is a unique sequence of information that determines everything from our eye color to our predisposition for Alzheimer’s disease. It may even influence our personalities.

Furthermore, there is a fundamental question about whether a genome can ever truly be de-identified, meaning we risk corporations being able to trace anonymized genetic material back to our identities. In 2013, researchers successfully re-identified individuals from anonymized genetic data by linking their genomes to publicly accessible genealogy databases. Later, in 2018, another research team showed that with access to a genetic database representing just 2 percent of a population, it was possible to match nearly anyone to at least a third cousin, highlighting how distant familial connections can be used to trace individual identities. This capability has been exploited by law enforcement to identify suspects, such as in the high-profile case of the “Golden State Killer.”

It’s undeniable that genomic data holds tremendous research potential, but commodifying it threatens to de-personalize something intrinsic and core to our identities.

Even if you haven’t committed a crime, you should still worry about your genome being exploited or weaponized against you. In 2023, the U.S.-based genetic testing company 1Health.io (formerly Vitagene) was accused of modifying its privacy policy and sharing customer data with third-parties — who could theoretically use genetic information to create targeted marketing schemes — without obtaining explicit consent from consumers. Additionally, recent allegations claim that the Chinese government used genomic data to surveil ethnic minorities and generate visual representations of citizens to use in facial recognition systems.

These incidents follow a troubling legacy of scientific inquiry that centered around the abuse of human bodies. Viewed as objects for extraction, these bodies were valued for the rich information they contained, with little regard to the persons they came from. Perhaps the most well-known example is that of HeLa cells, a line of self-regenerating cells taken from Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman living near Baltimore in the 1950s. Lacks’s family only recently reached a settlement with Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. in 2023 for the commercialization of her specimens, 70 years after they were taken without her consent.

Genomic data — digital sequences of nucleotide base pairs that form the blueprints of our bodies — may be intangible, but they are our specimens, linking us to our past and our future, and connecting us to others around the world. Even if genetic data is initially obtained with consent, federal regulation does not meaningfully regulate its sale nor require individuals be compensated for any financial gain resulting from their data. And unlike specimens of the past, the digital form of genomic data facilitates limitless copying or sharing, augmenting both its scientific potential and its risks of exploitation.

Some of these gaps could be addressed by the Genomic Data Protection Act, a bill that has been introduced twice to the Senate, by requiring “direct-to-consumer genomic testing companies” to easily enable consumers to access and request the deletion of their genomic data and biologic samples. However, the legislation in its current form would not require obtaining consent before sharing or selling this data. Further, the stipulations in the bill would only apply to entities that directly obtain data from consumers and includes explicit carve outs for “deidentified genomic data.”

Our current regulatory landscape has enabled the growth of business models that are built directly on the commodification of genomic data. Earlier this year, health data company Truveta announced the Truveta Genome Project, a database of genomic data linked to patients’ de-identified medical records. The project aims to build the world’s largest genetic database by sequencing biospecimens from partner health care providers that are left over from routine testing. Truveta will seek specific consent before sequencing a patient’s biospecimen, but they are not required to, as the data would already meet the definition of de-identified. Health care providers will be reimbursed when Truveta clients purchase data originating from their patients, which CEO Terry Myerson has argued will create the necessary financial incentives to power the business model.

It is vital that genomic data be treated not as economic assets but rather as identifiable specimens that are intrinsically tied to individual identity.

This model reduces genomic data to assets that can be owned and sold — all without direct benefit to the individuals they came from and without guarantee that their genomes are protected from re-identification and exploitation by morally unscrupulous businesses. Some safeguards under the Genetic Information and Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 prohibit the use of genomic data by employers and health insurance companies, but the scope of this legislation is narrow, notably omitting life and disability insurance providers, as well as other private companies. But as the lines between research and business continue to blur, it is vital that genomic data be treated not as economic assets but rather as identifiable specimens that are intrinsically tied to individual identity.

Given the unique, traceable, and deeply intimate nature of our genomes, federal regulations must evolve to prohibit the sale of genetic data without explicit consent and require that individuals receive compensation when profits are derived from their genetic information. Without such protections, we risk repeating a long and painful history of scientific exploitation — but this time, in digital form.

Anish Kumar is a student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, a medical fellow at the Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics (FASPE), and an incoming internal medicine resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

great piece! most interesting to me is the question of whether genomic data can ever truly be de-identified, although it is being treated as if it can when bought and sold. if government regulations aren’t helping to safeguard, could there be a moral standard enforced by genomics companies themselves or even start-up funders moving forward?