To Curb Online Sexual Abuse of Children, Experts Look to AI

Amanda Todd was 15 years old when, in September 2012, she uploaded a nearly nine-minute video to YouTube that detailed years of cyberbullying, harassment, and extortion. The abuse left her traumatized and depressed, Todd said. As a result, she turned to self-medication with drugs and alcohol, and, eventually, self-harm and cutting.

The British Columbia high school student took her own life about one month later.

Todd’s harasser was later identified as Aydin Coban, a Dutch national more than twice her age. Coban had met Todd in an online chatroom, pressured Todd to show her breasts, then began a ruthless three-year online harassment campaign. He revealed her identity, and according to news reports, sent photos to many of her classmates and friends. In 2022, Coban, who was already in prison in the Netherlands for similar charges, was sentenced to additional time for extorting and harassing Todd.

Cybersecurity analyst Patrick Bours began looking into the case in 2015, several years after Todd’s death. His children were 12- and 13-years old at the time, around the same age as Todd when she began to be cyberbullied.

“My son was playing a lot in these online games with his friends but also with strangers,” Bours said. Knowing that this happened to a girl around the same age, Bours said, the story stuck with him.

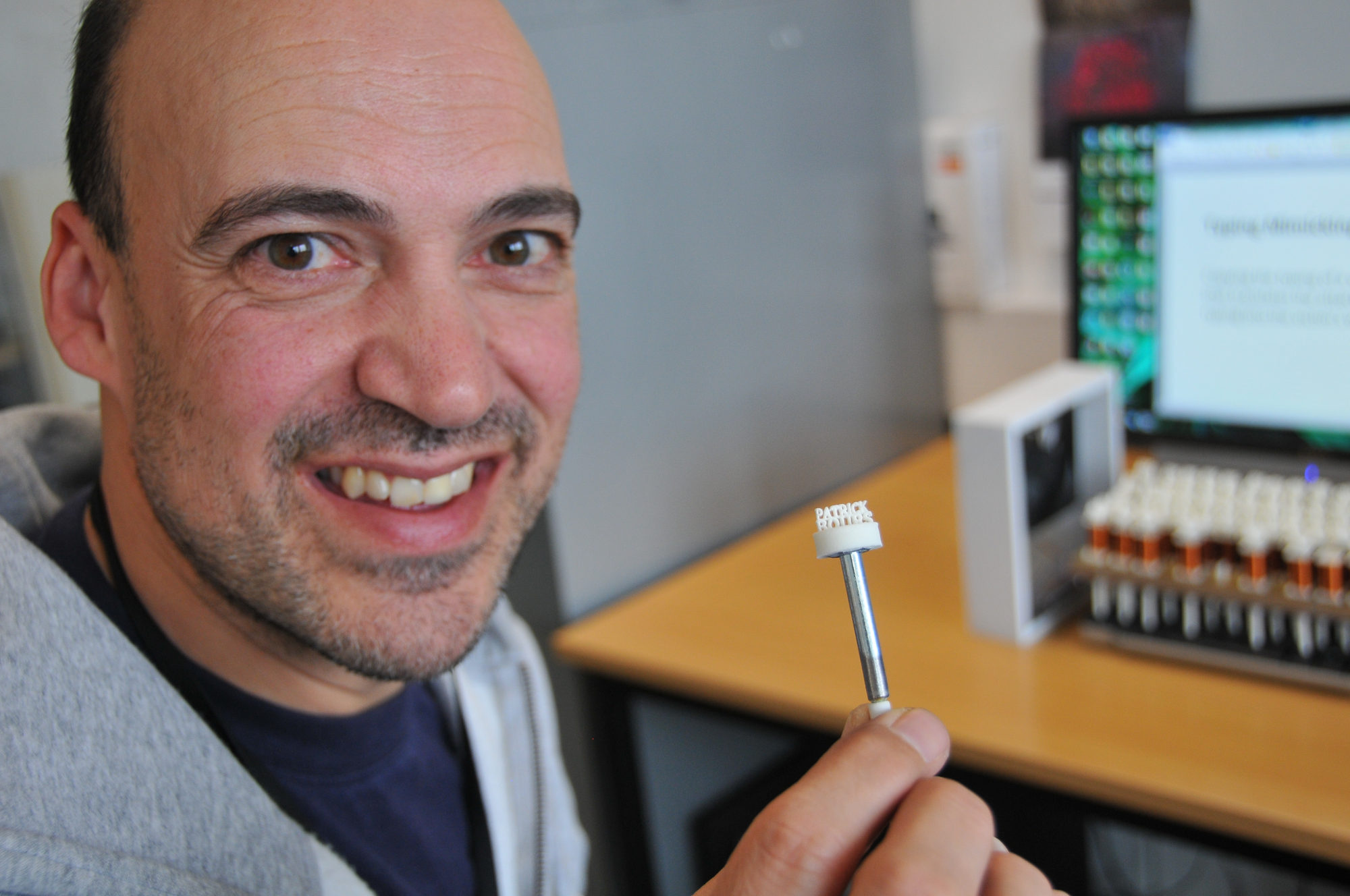

Bours, a professor of information security at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, was interested in applying his cybersecurity and cryptography skills to the larger issue of online safety for pre-teens and teenagers.

What could have happened if we would have been able to monitor the conversation and tell Amanda that he likely was a predator, Bours recalled asking one of his graduate students.

“Maybe nothing,” he said, or “maybe she would have stopped chatting.”

Cybersecurity researchers believe they could answer some of these questions — and help make children and teens safer online — through artificial intelligence.

Bours and his colleagues, for example, have developed a digital moderation tool — named Amanda, after Todd — that can accurately detect a predatory chatroom conversation, the researchers say, within an average of 40 messages when the tool was first tested in 2019. The accuracy has not been independently verified.

“That’s the difference between stopping something and a police officer having to come to your door and ‘Sorry, your child has been abused,’” said Bours, who previously was a cryptographer for the Netherlands National Communication Security Agency.

The application is already being used by a Danish game developer called MovieStarPlanet.

By training algorithms to identify abusive online conversations, like the kind experienced by Todd and millions of youths every year, the hope is that young people will be better protected from predators. (Bours did not notify the Todd family about the Amanda tool; Todd’s mother was not aware of the tool until contacted by Undark.)

“This is a new, exciting frontier for AI. This has the possibility to help us think about what positive use cases can be,” said Desmond Upton Patton, a technologist based at the University of Pennsylvania whose work focuses on the intersections of social work, data science, and ethical artificial intelligence.

“That’s the difference between stopping something and a police officer having to come to your door and ‘Sorry, your child has been abused.’”

But experts including Patton cite concerns around privacy, transparency, and inclusion. Patton said he hopes that developers include young people in the process “because we also need to understand their privacy concerns and what challenges and concerns they may have with this type of tool.”

We need to make sure that parents are aware and understand “how these tools work,” added Patton.

Manja Nikolovska, a London-based cybersecurity researcher, echoed such concerns. “Addressing these challenges will require a thoughtful approach,” she wrote in an email, that includes “empathetically tackling the reservations many users have about AI solutions, particularly regarding their implications for privacy, security, and ethical use in safeguarding children.”

The online sexual abuse of children and teenagers is a serious concern among law enforcement, child welfare advocates, and government officials around the world. The threat is extensively researched across disciplines, from child psychology and public health to computer science and cybersecurity.

According to one 2024 report by researchers based at the University of Edinburgh, the current scale of child sexual abuse material is “huge” and “should be treated like a global pandemic.” They estimate that one in eight children experienced sexual solicitation online in the prior year and 300 million children were affected by online sexual abuse and exploitation during the same period.

Other research has found similar figures: In a survey conducted in 2021 of more than 2,600 young adults in the U.S., for example, about 16 percent retroactively reported being abused online as minors.

According to one 2024 report, the current scale of child sexual abuse material is “huge” and “should be treated like a global pandemic.”

Cybergrooming — when an adult develops trust and builds an emotional connection with a minor or young adult online, with the intent to abuse them — has also reportedly increased. The FBI has noted that these predators often pose as children or teens.

But experts say that cybergrooming is understudied, which makes it more difficult to develop effective interventions. In a literature review, Nikolovska, who is also a research fellow at the Dawes Center for Future Crime at University College London, identified 135 published papers at the time that addressed cybergrooming.

One of the major research gaps is the lack of cyber-specific research, said Nikolovska during a Zoom call from London.

Many researchers and law enforcement agencies, she said, try to transfer existing knowledge about predators in the physical world to online spaces — such as gaming or social media — but online behavior looks much different. Online predators can disguise their identity, for example, or create private chatrooms for messaging. They also have easier access to strike up conversations in the first place: A 12-year-old may know to avoid speaking to a random stranger on the street but be more likely to respond to a message online.

Given that access, cybergroomers may target more victims in a much shorter window of time. In the case of one Finnish online predator, Nikolovska found, it only took an average of three days for the predator to contact a child, establish trust, and ask for a photo or meeting. The dataset was limited and specific to only one predator who targeted 14 female victims. But given that timeline, she said, it’s critical to develop digital interventions that could quickly identify and prevent cybercrimes.

One potential avenue to alert chatroom users in real time if someone is likely misrepresenting their age or gender involves an emerging technology called keystroke dynamics, which analyzes typing patterns, including speed, intervals between keystrokes, and how often the person uses certain keys such as “Caps Lock.”

Researchers in Norway, Nigeria, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere have published papers in recent years around keystroke dynamics, artificial intelligence, and age and gender detection with varying degrees of success.

And several Nordic countries, including Finland and Norway, have prioritized developing artificial intelligence for social good. This could be among the reasons why those governments are funding cybersecurity and computer science research around online child sexual abuse, said Nikolovska.

For example, cybersecurity analyst Oliver Tverrå is one of more than 100 graduate students who have studied under Bours at the Norwegian Biometrics Laboratory. Tverrå’s 2023 thesis investigated how variables such as key press duration, typing accuracy, and speed, could predict the author’s age and gender in real time. Generally, the greater the number of messages sent, the higher the accuracy in determining age and gender.

But the experiment encountered one major challenge: To determine a messenger’s gender with 87.5 percent accuracy, the model required more than 1,600 keystrokes. That could be hundreds of words.

The algorithm they tested is not robust enough, Tverrå said in a Zoom interview from Norway. Researchers need more time and larger data sets to develop more accurate models, he added. The dataset Tverrå used was limited to 56 people total.

And if a user believes a system to be more effective at identifying predators than it actually is, he added, that may lead them to “trust a person they should not trust.”

The Amanda digital moderation tool that Bours developed uses a different type of artificial intelligence to detect predators: natural language processing, which analyzes words and sentences to understand the intention of the person sending the message.

One goal is to identify the type of cybergrooming that targeted Amanda Todd. But the AI could be tailored to detect a broad range of predatory or dangerous behavior, the developers say, such as bullying, harassment, radicalization, or even self-harm.

Currently, the Amanda tool requires a client — such as a gaming or social media app — to sign up for its services. Users grant the apps access to their posts and direct messages as part of the client’s terms of service. Once installed, Bours said, the tool continuously analyzes users posts and messages, then assigns a risk score. Posts and messages with higher scores may need to be reviewed by a human moderator. The tool is also programmed to update the risk score each time there is a new message.

“Let’s say that the risk of this conversation is seven,” said Bours. “If we evaluate a risky message like, ‘Are you home alone, sweetie?’ — that’s a risky message and the risk will go up from seven to nine or whatever.”

When the risk score reaches a certain threshold, the system then automatically deletes the messages, forwards the scores, and flags any potential violations to the client’s digital moderation team.

If a user believes a system to be more effective at identifying predators than it actually is, that may lead them to “trust a person they should not trust.”

The human moderator would look at the conversation and could say, “It’s just a normal conversation between two adults,” said Bours. Or, if there is a grooming conversation ongoing, the moderator could take action. And the predator could be blocked or removed from the platform, he added.

If it’s a very serious situation then the client could reach out to the authorities, he added.

The algorithm was initially trained on an archived dataset of millions of messages between sexual offenders and people posing as children. The developers later expanded the training set using customer data. The machine learning models are trained to recognize risky messages and grooming conversations, the researcher explained. The final dataset included about 28,000 conversations from about 50,000 authors including hundreds of predators.

Bours and his colleagues created a spin-off called Aiba AS in 2022 to market the Amanda tool and other AI trust and safety products. And in 2023, the developers signed their first agreement with law enforcement. The understanding with the Innlandet Police District, in eastern Norway, allows the developers to train their system on the chat logs of predators that were investigated and prosecuted.

Artificial intelligence models and algorithms are only as good as the datasets they are trained on. One of the major flaws in researching automated predator detection, Nikolovska wrote in an email, is that most models are trained on datasets “using chat data that does not originate from actual cases of cyber grooming.”

The Amanda application appears to be an “incredible advancement” since it is based on real-life cases, said Nikolovska, who was not involved in the research.

The algorithms that train on word cues are an important tool to detect grooming, she said, but cautioned that predators could become more sophisticated. “The potential is great,” she said. But since these algorithms mainly rely on explicit words — such as sexual words — or manipulative words, then the offenders could adapt and “tone down their language” to avoid detection, she added.

Nikolovska is also concerned about transparency and privacy in Amanda and other automated predator detection models. The system should explain why specific chat conversations are labeled as predatory or non-predatory, she said, so that users understand exactly what triggers the system.

There also should be safeguards as to what personal data should be collected, how it should be stored, and if it can be shared with authorities, said Nikolovska. The Amanda AI does not store messages or conversations directly, Bours said; that data is stored by the client companies.

In the case of the Amanda tool, no information is shared with parents or third parties, said Bours.

One of the major flaws in researching automated predator detection is that most models are trained on datasets “using chat data that does not originate from actual cases of cyber grooming.”

Patton, the University of Pennsylvania technologist, is also cautiously optimistic about the Norwegian chat moderation app. The research and developments are important and appear to be a responsible use of artificial intelligence, said Patton, who did not work on this project and has developed several AI models to link at-risk youth to behavioral health and trauma interventions.

In 2018, for example, Patton led a research laboratory at Columbia University that spearheaded development of a pioneering AI model that searched Twitter timelines to identify grieving and anger among Chicago-area youth.

It’s key to integrate various perspectives, he said, because these algorithms should not “be created just by AI engineers.” The gun violence algorithm created by Patton’s team included youth perspectives, for example.

The Amanda tool and similar systems should include input from young people as well as mental health practitioners — such as psychiatrists, social workers, and psychologists — to ensure the developers are not creating additional harms, Patton told Undark. “I would like to see some of this work happen in more simulated environments first. We’re not guinea pigs — we are real people with real feelings and real emotions.”

One such example of a simulated environment: developing chatbots to imitate interactions with online predators.

Computer science researchers based at several universities in the United States — including the University of California, Davis; Virginia Tech; and Vanderbilt University — are developing educational chatbots for children and teens. The chatbots would teach students how to recognize and respond to online predators.

Much of the current AI research around online predators is designed to detect the cybergroomer based on conversations, said Lifu Huang, a computer scientist based at UC Davis. Those models are helpful but do not educate youth on how to recognize and respond to online predators, he said, adding that “simulating such conversations could be more powerful” in detection.

Huang is part of a research team that was awarded a three-year National Science Foundation grant in 2024 to create an educational chatbot for adolescents. The research leverages natural language processing and large language models — such as the popular ChatGPT — to develop human-like chatbots that can simulate a conversation between predators and youth. The goal is to use the chatbot for education in schools, classrooms, and nonprofits.

Huang and his colleagues, which includes computer scientist Jin-Hee Cho at Virginia Tech, has developed a working model nicknamed SERI for “Stop CybERgroomIng.” The platform includes two human-like chatbots — one that mimics the online perpetrator and the second that mimics a young victim.

There is significant interest in the project because this would be the first educational chatbot to teach teenagers how to respond to cybergroomers.

But there are some limitations. The archive of grooming conversations that the perpetrator chatbot was trained on, for example, is more than 10 years old. This could mean that the chatbot won’t recognize more recent language, Huang said. To address this, the team is collaborating with other researchers to conduct human-based studies to yield more up-to-date training data. The researchers hope to capture higher quality training data by this summer.

Privacy is a major concern when developing a chatbot intended for tweens and teenagers, said Huang. So, the research team is using publicly available datasets and have avoided online sources like OpenAI, Huang explained. The SERI chatbots are also not able to collect or store any information or data while role-playing.

The potential to develop artificial intelligence to address, detect, or prevent online predators could be major advances to curb a serious social problem. “This is an exciting frontier for AI,” said Patton. But “we have to approach this in a thoughtful way, prioritizing ethics and inclusivity and collaboration.”

“If done well,” he added, “I think this work has the potential to not only protect young people, but to also build trust in digital platforms, which we so desperately need.”

Still, some challenges remain. For one, the success of digital moderation tools such as Amanda depends on widespread adoption, said cybersecurity researcher Manja Nikolovska. It’s unclear how many gaming and social media platforms will sign up to integrate the technology into their messaging and forum apps. Amanda app clients include MovieStarPlanet, a Danish-based social and online game for children and teens that counts 10 million active monthly users.

At the same, more academic research should be conducted into the adoption of these tools, said Nikolovska in an email. “Success in this area will also depend on exploring children’s reactions: whether they find ways to bypass the controls of such systems and whether there is a “die-off” period (discontinuation of use) after initial adoption.”

The Federal Bureau of Investigation believes there are more than 500,000 online predators active every day and each has multiple online profiles. Police and law enforcement say they are not able to prevent most predators from making online contact with children, and it will take a multi-prong effort by social media and gaming platforms, parents, children, technology developers, advocacy groups, and others.

“If done well, I think this work has the potential to not only protect young people, but to also build trust in digital platforms, which we so desperately need.”

Recent months have seen a renewed interest in the role of social media giants in online abuse targeting youth. New Mexico Attorney General Raúl Torrez, for example, filed a lawsuit against the company that owns Snapchat in September that claims the popular application has done very little to curb grooming, sexual harassment, and sextortion — when someone acquires sexually explicit images from a person, then uses that material as blackmail for either money or more images.

And last October, Todd’s family joined 10 other families in a lawsuit against Snapchat, Meta, and other tech companies alleging the companies prioritized engagement over children’s safety.

Bours, the cybersecurity analyst and cryptographer who launched the Amanda tool, is hopeful that content moderation, keystroke analysis, and similar technologies could address many of these cases. And, possibly, prevent more teenagers from experiencing the same torment as Todd.

Bours has no plans to stop his research. “This is something that I will be doing for the rest of my academic career.”

McCullom reported this story from Trondheim, Norway, and Chicago, Illinois.

If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org.