For Many, Weight-Loss Drugs Are Pricey. Expanding Access Is Hard.

In the coming year, President Donald Trump’s administration will face a choice: Spend billions of dollars to cover anti-obesity drugs under Medicare and Medicaid, or deny more than 7 million people access to a potentially lifesaving treatment. The decision represents an inflection point in how the U.S. pays for health care. What happens when millions of Americans stand to benefit from an innovative treatment, but it’s priced so high that most can’t afford it?

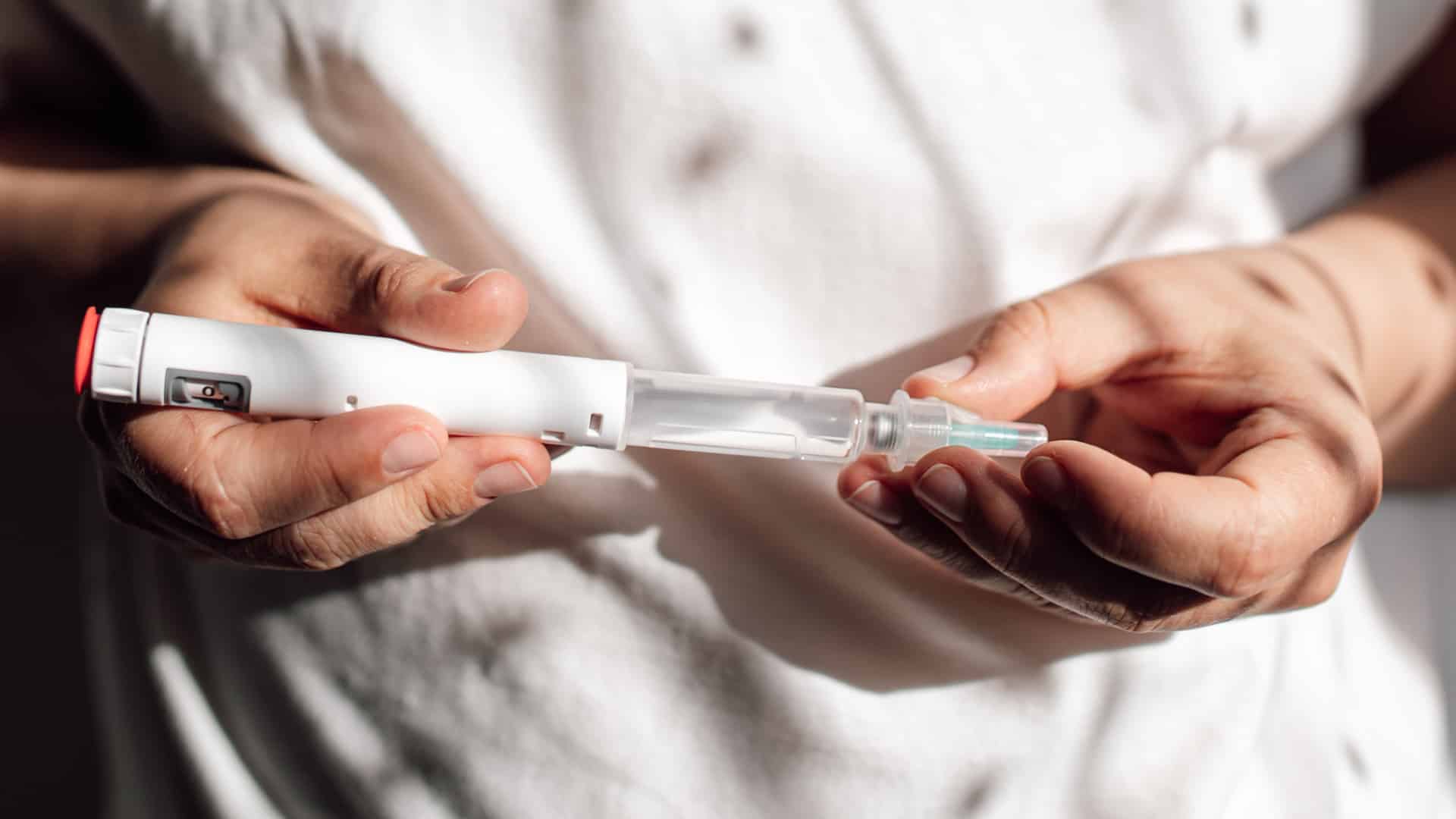

The newest generation of anti-obesity medications — Saxenda (liraglutide), Wegovy (semaglutide), and Zepbound (tirzepatide) — belong to a category of drugs known as GLP-1 agonists, or GLP-1s. Their effectiveness against diabetes, obesity, heart disease, sleep apnea, and a growing list of other conditions has rocketed the drugs to blockbuster status: One in eight U.S. adults has taken a GLP-1 drug, according to a May 2024 poll conducted by the nonprofit health policy organization KFF.

But many people can’t afford them. At least partly due to their high cost — for example, annual list price for Wegovy is around $16,000 or more — Medicare as well as most state Medicaid plans have only covered the drugs for diabetes. Private insurers are also struggling with the costs. Last year, only around one in five large U.S. companies covered GLP-1s for weight loss in their health plans, according to results from a KFF survey published last October in the journal Health Affairs.

Changes in coverage can have big effects on budgets. Last spring, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services opted to cover Wegovy for people with heart disease who are also overweight or obese without diabetes. That decision will add $10 billion to annual Medicare spending, according to the most conservative estimate from a recent analysis published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

And if the Trump administration upholds a proposal from former President Joe Biden’s administration to further extend GLP-1 coverage for obesity alone? That would undoubtedly add billions to federal and state spending, said the lead author of the Annals of Internal Medicine study, Alexander Chaitoff, an internist and health policy researcher at the University of Michigan.

“At current prices, it would be incredibly difficult to pay for these drugs and get them to all of the people that would likely want to use them,” said Chaitoff.

Some health policy experts contend that broader coverage will enrich drug companies without necessarily making Americans healthier.

To maintain weight loss, people may need to stay on GLP-1s indefinitely, and the long-term risks are uncertain, said Scott Atlas, a health care policy expert at the Hoover Institution, a conservative think tank at Stanford University, and a medical adviser during the first Trump administration. “We’re playing with fire here, and it’s a rush to demand insurance.”

“At current prices, it would be incredibly difficult to pay for these drugs and get them to all of the people that would likely want to use them.”

However, several major medical organizations support GLP-1 treatment for obesity. One of those groups, the American Medical Association, has even urged insurers to cover the medications.

Now, a growing chorus of advocates are calling on legislators to solve the price-access conundrum by, in part, strong-arming drug makers into lowering prices. It’s unfair that Novo Nordisk charges far more for Wegovy in the U.S. than in other countries, wrote 253 members of the nonprofit advocacy group Doctors for America in a letter submitted to a U.S. Senate hearing on GLP-1 pricing last September. A month’s worth of Wegovy, which lists for $1,348 in the U.S., costs $186 in Denmark, the group pointed out, and just $92 in the United Kingdom.

“Senators,” they implored, “we are asking you to do everything in your power to bring down the price of these novel diabetes and obesity drugs.”

One of the signatories of the Doctors for America letter was Reshma Ramachandran, a Yale University health researcher and family physician who treats underserved populations. Her patients are affected by chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and obesity, she said. And one of the barriers standing between them and effective treatment with GLP-1s, she added, is consistent insurance coverage for the drugs: “The medications are incredibly hard to access.”

Ramchandran said that she has to jump through hoops to try to convince insurers to cover the expensive drugs even for patients who could clearly benefit, like those with diabetes or who are overweight and have cardiovascular disease. And even then, she said that she is not always successful.

Cheaper compounded versions of GLP-1s are still too expensive for most of her patients, said Ramachandran. (These compounded GLP-1s, which are created in pharmacies, are not FDA-approved, and the agency has repeatedly warned about problems with some formulations.)

The simplest reason drug makers charge so much in the U.S., said Ramachandran, is because they can. Unlike in other countries, she said, there’s no mechanism in the U.S. to negotiate the launch price of a new drug, meaning that drug companies can set the initial price as high as the market will bear.

Thanks to patents and periods of exclusivity granted by the Food and Drug Administration, the makers of new drugs enjoy years of access to the market before generic makers are legally allowed to make an unbranded version. A 2023 analysis published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that, on average, GLP-1s are protected from generic competitors for 18 years after FDA approval.

During that window without competition, drug makers set list prices high, knowing that they will net somewhat less after intermediary companies called pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, negotiate rebates and discounts for the insurance programs that they represent.

For example, research suggests Novo Nordisk nets about $700 for a month’s worth of Wegovy, just over half the list price.

Even that price, data suggests, represents a huge markup.

Factoring in the costs of production, logistics, and taxes, Novo Nordisk could sell injectable semaglutide (sold as Wegovy for weight loss and Ozempic for diabetes) for less than $5 per month and still make a 50 percent profit, according to a 2024 analysis in JAMA Network Open that was funded by Access Campaign of Doctors Without Borders, a nonprofit medical aid group.

“I’m grateful that it wasn’t my first rodeo,” said the study’s lead author, Melissa Barber, a Yale School of Medicine health economist who has estimated the production costs of thousands of drugs. Otherwise, she said, “people wouldn’t have believed me because the results were so appalling.”

Novo Nordisk could sell Wegovy for less than $5 per month and still make a 50 percent profit, according to a 2024 analysis

The cost estimate by Barber and colleagues is a “misleading oversimplification,” Novo Nordisk spokesman David McAlpine wrote in an email. “By the authors’ own admission, their model ignores the cost of creating something out of nothing and bringing it to market,” he wrote, noting that the company spent $10 billion developing GLP-1s and more than $30 billion in the last year on expanding production.

In written testimony submitted to the September Senate hearing, Novo Nordisk CEO Lars Fruergaard Jørgensen justified the company’s U.S. pricing based on those development and research costs and the value to patients. Ramachandran scoffed at that idea. The products have been on the market long enough that the company has already made tens of billions of dollars, she said: “They’ve gotten their return on investment and then some.”

For his part, Jørgensen placed the blame for high U.S. drug prices squarely on PBMs. Because the PBMs receive fees based on a percentage of a drug’s list price, they favor more expensive drugs, he testified in the hearing. “Which means that in our experience, products that come with a low list price get less coverage,” said Jørgensen. “It’s less attractive.”

Meanwhile, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont told the committee that he had commitments in writing from the major PBMs that they would not limit access to Wegovy or Ozempic if Novo Nordisk lowered its prices.

The obvious solution to the affordability crisis, according to Ramachandran and others, is for drug makers to charge less. But other than shaming pharmaceutical executives in a public forum, lawmakers have few options for controlling drug pricing.

In an op-ed for the health news website STAT, Ramachandran, Barber, and primary care physician and health policy research Joseph S. Ross facetiously suggest that it would be cheaper in the long run for the federal government to simply buy Novo Nordisk for its market value of $606 billion than to pay the company for its products.

Barring buying the company outright, the U.S. government could buy the license for Wegovy, the researchers suggested, and then grant the rights to another company to make a cheaper generic. The CEOs of major generic pharmaceutical firms said that they could market generic semaglutide for less than $100 month, according to remarks by Sanders in the Senate hearing. As it is, generic maker’s hands are tied until the patents for semaglutide products expire. (According to Novo Nordisk’s 2023 annual report, the patent for Ozempic expires in 2032.)

However, with potentially better treatments on the horizon, pre-empting the market is not a good idea, said Joseph Levy, a health economist at Johns Hopkins University. “What that would mean is that the government was choosing a winner here,” he said. “There’s probably going to be incremental improvements over time in the quality of these drugs, whether they have more weight loss effects or possibly less adverse events and side effects.”

In its final week, the Biden administration added three GLP-1s, including Wegovy, to the list of medications covered by Medicare that the federal government is allowed to haggle over. Several experts told Undark that those negotiations represent a realistic path to lowering costs.

“How they choose to set that price will be extraordinarily important for medium term-to-longer-term costs,” said Benedic Ippolito, a health economist at the American Enterprise Institute, a right-leaning public policy think tank. If Wegovy costs less, then competitors will also have to cut their prices.

Other than shaming pharmaceutical executives in a public forum, lawmakers have few options for controlling drug pricing.

But those lower prices, scheduled to take effect in 2027, may not spill over into the private insurance market, Ippolito wrote in an email. “I expect that Medicare negotiation will have minimal effects on prices in the commercial market,” he wrote.

Ramachandran disagrees. The big insurance companies, which are also involved in managing Medicare Advantage and some Medicaid plans, often look at the Medicare prices as a starting point for their own negotiations, she said.

Even if the government takes no action, market forces will eventually bring prices down, said Levy. While the list prices for GLP-1 have remained stubbornly high, the net prices have come down as competitive products entered the market, he said.

Atlas, the Stanford health economist, sees a possible delay in widespread access to GLP-1s as an opportunity. He’d rather see resources invested in a public health initiative focused on the health risks of obesity along the lines of anti-smoking campaigns. “It’s embarrassing as a medical scientist to hear people ignoring all that and now rushing to a drug,” he said.

Health professionals should emphasize nondrug approaches to combatting obesity, said Atlas, and “it can be fixed or modified or lessened — the studies are there — by diet, by exercise, by education.”

That vision runs counter to the official guidelines of the American Gastroenterological Society, which concludes that many people just aren’t able to shed pounds through lifestyle changes. The Society’s experts analyzed six clinical trials that followed participants for a year or longer while they tried to lose weight either through a combination of diet, exercise, and medication, or through lifestyle changes alone. Overall, 30 percent of the diet-and-exercise group lost 5 percent or more of their body weight, compared to about 80 percent who also took a GLP-1.

Nonetheless, Atlas would like to know more about the longer-term effects of GLP-1s before they are prescribed to a large swath of Americans. Postponing coverage would buy time to conduct much-need safety studies, he said. “I prefer the idea of being very cautious here, being conservative in terms of developing drugs, doing safety studies, doing efficacy studies, doing other measures that are completely non-hazardous,” he added. “And in the meantime, letting drug manufacturers start competing.”

For the millions of Americans with obesity who are on Medicare and Medicaid the simplest way to improve access to GLP-1s would be for those programs to provide full coverage. Whether that’s feasible at current prices, though, remains a topic of debate.

Levy and Ippolito, the price analysts, said that many scientific publications and reports in the press have overestimated the cost to Medicare. “People were just kind of taking the list price of the drug and multiplying it by estimates of how many obese people there are,” said Levy, “and say ‘This is going to bankrupt the federal government’.”

In the real world, insurers generally pay less than the list price. And only a fraction of eligible patients winds up taking GLP-1s long term, said Levy. Plus, if patients are successful in losing weight, that might result in health benefits that save the system money. Accounting for those factors, Levy and Ippolito published what they consider a realistic assessment of the Medicare costs to cover GLP-1s for obesity in Health Affairs last September. If, as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS, anticipates, 10 percent of eligible Medicare patients receive the drug, the economists estimate that part D drug plan costs would increase by more than $6 billion each year.

A staggering sum, even if it’s less than many people expected, said Ippolito. “It’s extraordinarily weird to me to be in a position of saying some incremental policy change is going to affect spending by tens of billions of dollars over a budget window and people being like, ‘that’s it?’” he said. “That’s kind of a lot.”

“I prefer the idea of being very cautious here, being conservative in terms of developing drugs, doing safety studies, doing efficacy studies, doing other measures that are completely non-hazardous.”

If public and private insurers expand GLP-1 coverage, everyone is likely to feel the impact, said Chaitoff. “Eventually we pay the price for it,” he said. “If these medications are costing a lot and insurers are paying for it now, in the next year, or the next year, eventually that goes into your premium.”

In addition, GLP-1 expenditures may displace funding for treatments such as exercise programs and nutritional counseling. While Barber favors expanding access to GLP-1s, the cost will inevitably eat into funding for other services, she said. “I wish people were talking more about the trade-offs,” she added. “If Medicare funds this, what can’t it fund?”

Whether the Trump administration will require Medicare and Medicaid to cover anti-obesity drugs remains an open question, as prominent Republican advisers disagree on the best ways to “make America healthy again.”

In an October interview with Fox News, Robert F. Kennedy, President Donald Trump’s pick for health secretary, decried both the utility and cost of GLP-1s, which he pegged as $3 trillion annually — a widely inflated number he seems to have calculated by multiplying a too-high list price by the number of overweight Americans. “They’re counting on selling it to Americans because we are so stupid and so addicted to drugs,” Kennedy said.

But by his January confirmation hearing before a U.S. Senate committee, Kennedy seemed to have softened his stance, referring to GLP-1s as “miracle drugs” — although he warned that covering GLP-1s for all Americans who are overweight would lead to a “tsunami” of costs for federal and commercial insurers.

Support Undark Magazine

Undark is a non-profit, editorially independent magazine covering the complicated and often fractious intersection of science and society. If you would like to help support our journalism, please consider making a donation. All proceeds go directly to Undark’s editorial fund.

Meanwhile, Mehmet Oz, who Trump has nominated to lead CMS, promoted GLP-1s on his website and ran lengthy infomercials sponsored by Novo Nordisk on his eponymous television show, according to reporting from The Washington Post.

And technology titan and Trump adviser Elon Musk, who referred to himself as “Ozempic Santa” in a December post on his social media site X, is a strong proponent of increasing access to GLP-1s. “Nothing would do more to improve the health, lifespan and quality of life for Americans than making GLP inhibitors super low cost to the public,” Musk posted on X.

Atlas, who has advised several Republican presidential candidates in addition to Trump, said that he’d like to see the incoming administration shoot down the proposal to expand GLP-1 coverage. “But I’m worried that they will lack political courage to say, ‘no, these drugs should not be covered by insurance at this point unless there’s an extraordinary clinical indication,” he said.

Ippolito is less sanguine about the fate of the proposed expansion: “I would not be surprised if they rescinded this policy both on the grounds that they don’t like the policy itself and on the grounds that they think it might be an overreach of legal authority.” By law, Medicare is prohibited from paying for weight-loss drugs. While GLP-1s represent an obesity treatment and are not intended for cosmetic weight loss, unless Congress explicitly overturns the ban, coverage could still be subject to legal challenge.

Restrictions on access to expensive drugs are like applying a Band-Aid to a deeply dysfunctional system, one expert said — one that staunches financial bleeding by denying vital treatments.

Still, as GLP-1s are inevitably FDA-approved for more indications and prices come down, the budget math for covering obesity treatment through Medicare and Medicaid will start to look more favorable to regulators, said Ippolito: “My guess is that they will eventually cover these within the next, say, five years or so.”

Private insurers are also likely to expand GLP-1 coverage in the next few years, Ippolito wrote in a follow-up email, although the cost may be reflected in higher premiums. Commercial markets aren’t likely to realize a big drop in GLP-1 pricing until the early 2030s, when generic makers are likely to enter the market, he wrote.

Similar cases highlight how those delays could cost lives. Barber recalled the case of the drug Sovaldi (sofosbuvir), a treatment for hepatitis C that cost $84,000 when it was approved in 2013: “It was a very, very effective drug for a very, very deadly disease.” But, due to the expense, many state Medicaid programs initially limited access to the lifesaving drug.

Restrictions on access to expensive drugs are like applying a Band-Aid to a deeply dysfunctional system, said Barber — one that staunches financial bleeding by denying vital treatments. “But because this drug is so astronomically expensive and potentially so many people are eligible for it,” she said, “it really forces us to deal with the kind of systemic flaws that we tried to paper over.”

Seriously? This poisoning must end!

https://open.spotify.com/episode/0lVGQl58XlT6MBb3lpskeV

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-13514453/Venomous-lizard-key-Ozempics-slimming-powers-breakthrough-drug-deadly-creature.html

https://medicine.uq.edu.au/article/2024/04/rise-ozempic-how-surprise-discoveries-and-lizard-venom-led-new-class-weight-loss-drugs

https://www.research.va.gov/research_in_action/Diabetes-drug-from-Gila-monster-venom.cfm