One bluebird day in 2021, employees of Fortem Technologies traveled to a flat piece of Utah desert. The land was a good spot to try the company’s new innovation: an attachment for the DroneHunter — which, as the name halfway implies, is a drone that hunts other drones.

As the experiment began, DroneHunter, a sleek black and white rotored aircraft 2 feet tall and with a wingspan as wide as a grown man is tall, started receiving radar data on the ground which indicated an airplane-shaped drone was in the air — one that, in a different circumstance, might carry ammunition meant to harm humans.

“DroneHunter, go hunting,” said an unsettling AI voice, in a video of the event posted on YouTube. Its rotors spun up, and the view lifted above the desiccated ground.

The radar system automatically tracked the target drone, and software directed its chase, no driver required. Within seconds, the two aircrafts faced each other head-on. A net shot out of DroneHunter, wrapping itself around its enemy like something from Spiderman. A connected parachute — the new piece of technology, designed to down bigger aircraft — ballooned from the end of the net, lowering its prey to Earth.

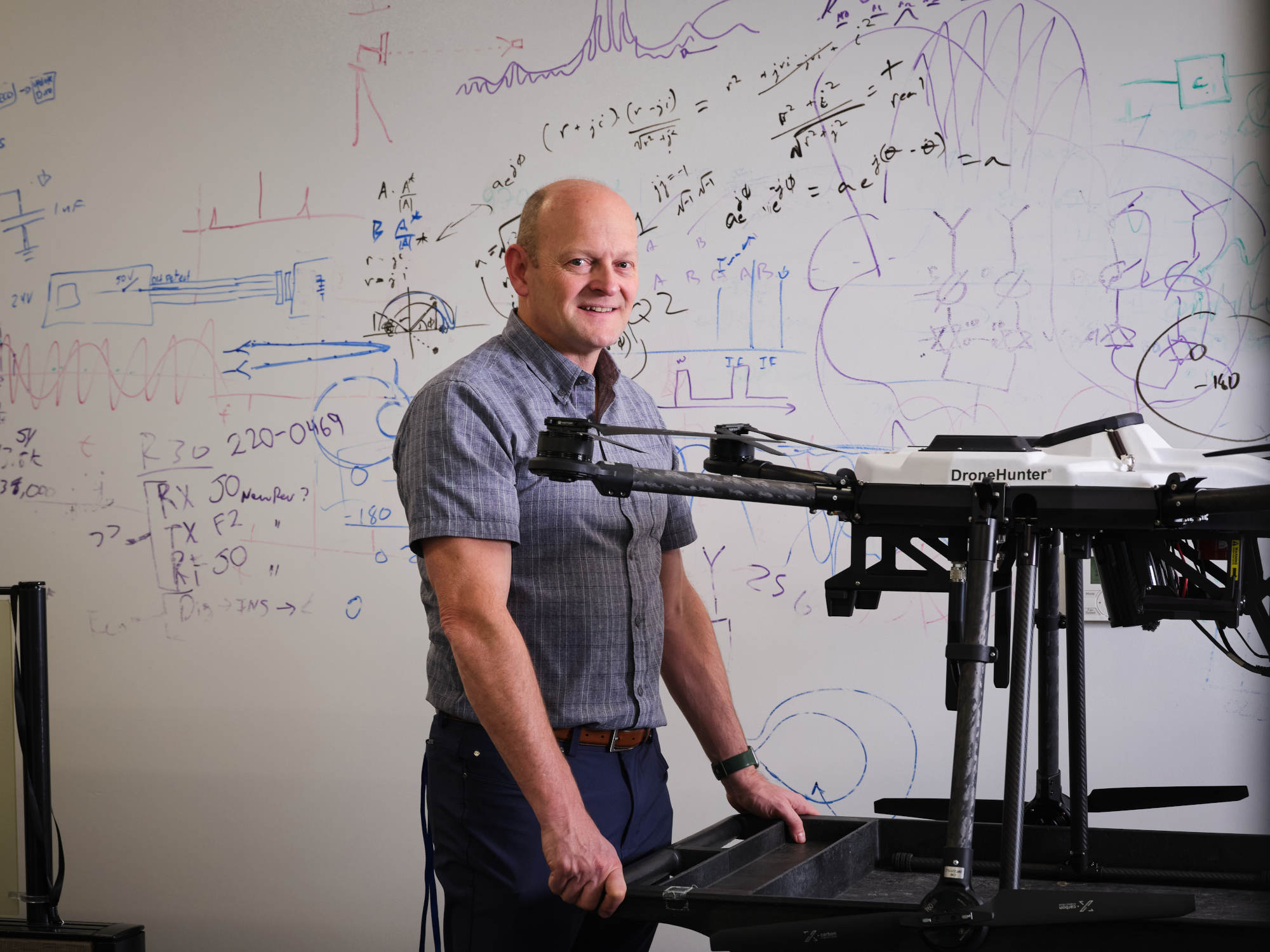

Target: defeated, with no human required outside of authorizing the hunt. “We found that, without exception, our customers want a human in that loop,” said Adam Robertson, co-founder and chief technology officer at Fortem, a drone-focused defense company based in Pleasant Grove, Utah.

While Fortem is still a relatively small company, its counter-drone technology is already in use on the battlefield in Ukraine, and it represents a species of system that the U.S. Department of Defense is investing in: small, relatively inexpensive systems that can act independently once a human gives the okay. The United States doesn’t currently use fully autonomous weapons, meaning ones that make their own decisions about human life and death.

With many users requiring involvement of a human operator, Fortem’s DroneHunter would not quite meet the International Committee of the Red Cross’s definition of autonomous weapon — “any weapons that select and apply force to targets without human intervention,” perhaps the closest to a standard explanation that exists in this still-loose field — but it’s one small step removed from that capability, although it doesn’t target humans.

How autonomous and semi-autonomous technology will operate in the future is up in the air, and the U.S. government will have to decide what limitations to place on its development and use. Those decisions may come sooner rather than later—as the technology advances, global conflicts continue to rage, and other countries are faced with similar choices—meaning that the incoming Trump administration may add to or change existing American policy. But experts say autonomous innovations have the potential to fundamentally change how war is waged: In the future, humans may not be the only arbiters of who lives and dies, with decisions instead in the hands of algorithms.

For some experts, that’s a net-positive: It could reduce casualties and soldiers’ stress. But others claim that it could instead result in more indiscriminate death, with no direct accountability, as well as escalating conflicts between nuclear-armed nations. Peter Asaro, spokesperson for an anti-autonomy advocacy organization called Stop Killer Robots and vice chair of the International Committee for Robot Arms Control, worries about the innovations’ ultimate appearance on the battlefield. “How these systems actually wind up being used is not necessarily how they’re built,” he said.

Meanwhile, activists and scholars have also raised concerns over the technology falling into the wrong hands, noting that even if a human remains at the decision-making helm, the end result might not be ethical.

Both the optimists and the critics do tend to agree that international safeguards and regulations should exist — ideally in a way that ensures some human accountability. Getting strictures like that in place, though, has been in the works for more than a decade, with little progress to show for it, even as the technology has advanced.

Autonomous weapons may seem futuristic, but they have technically existed for more than a century. Take landmines, for instance, which were first widely used during the Civil War and go off independently, with no discernment. Or punji sticks — sharp spikes intended to harm or trap soldiers. When someone steps on the covering of punji sticks hidden in a hole — a type of trap in wide use during the Vietnam War — they plunge down and land on the spikes.

Then there are heat-seeking missiles, which have been chasing infrared-emitting objects on their own since the 1950s. And the Navy still uses a system, first developed in the 1960s, to autonomously intercept projectiles sluicing toward ships.

“How these systems actually wind up being used is not necessarily how they’re built.”

Today, autonomy looks a bit different: Artificial intelligence can identify people by their physical characteristics, making it, in theory, feasible for militaries to target specific enemy combatants. Meanwhile, automatic navigation and tracking are much more sophisticated. Still, said Zachary Kallenborn, an adjunct fellow at the Center for Strategic & International Studies think tank, the term “autonomous weapon” encompasses too much. “It’s an incredibly broad scale of different things, some of which are probably very significant,” he said. “Others probably are not at all.”

The first potential use of a fully autonomous modern weapon was in Libya in 2020, when a drone may have self-directed to attack militia fighters, according to a United Nations report (though it is difficult to prove a human wasn’t in the loop somewhere). Since then, semi-autonomous weapons — with varying degrees of human involvement — have continued to appear on the battlefield: In Ukraine, autonomous drones are able to target people, although for the moment a human directs them to do so. In the ongoing conflict in Gaza, the Israel Defense Forces have reportedly used an AI-enabled data system called Lavender that chooses human targets based on behavioral patterns with “little human oversight,” according to an investigation by +972 Magazine and Local Call. Israel has also reportedly used domestic company Elbit Systems’ autonomous drones and AI software in battle, which has killed Palestinian civilians.

More such weapons may be coming: Anduril, an American company, has plans to build a factory that enables it to produce autonomous weapons on a large scale, and already has offerings like the ALTIUS-700M, an autonomy-enabled drone that can hover and attack with explosive munitions.

Such weapons are offensive, preemptively targeting and taking down humans or systems with bombs or missiles. These robots are not infallible, said Erich Riesen, a philosopher at Texas A&M University whose work on military ethics in this new autonomous age has been cited by influential defense thinkers. But they do operate according to rules that they cannot disobey: They are not, at least yet, morally autonomous. Humans, and the software they write, determine the weapons’ morals.

People are always starting the loop, said T.X. Hammes, a distinguished research fellow at the National Defense University, even if someday they’re not in it. “A human still has to be involved from the beginning,” he said, designing the weapon and laying out its parameters, meaning, in his mind, there is no such thing as full autonomy.

AI, though, could hypothetically take that original programming and make decisions outside the scope of what the initial humans imagined.

The rules a robot follows may not be perfect, and may lead to mistakes, but humans also make both errors and their own moral decisions. A soldier can get exhausted, or scared, and have their judgment impaired.

Other semi-autonomous weapons, though, deal only with incoming threats. That’s where Fortem’s work would fall, or that of the Iron Dome in Israel, which lobs missiles at incoming missiles.

Much of the latest technological development is fueled by governments and companies eager to get ahead of the weapons race. That appears to be the case with a recent U.S. initiative called Replicator that aims to deploy thousands of small, inexpensive uncrewed vehicles: ships, aircraft, and anti-drone devices — potentially like those Fortem makes — by August 2025. “The technology is ready,” said Eric Pahon, spokesperson for the deputy secretary of defense, in an emailed comment.

“Industry is ready,” he added.

“A human still has to be involved from the beginning.”

Some of Replicator’s systems will be armed, but it’s not necessarily clear what form their variety of weapons will take, or in what ways they’ll be used.

Despite the fuzziness, however, one thing is clear: Replicator is a kind of preparatory program for private companies. It shows the commercial sector that the government will want, and is willing to pay for, autonomous technology. That promise incentivizes companies to start investing their own resources in developing relevant innovations, according to the Defense Innovation Unit’s online description of the program. The Defense Innovation Unit exists within the DOD and plays a leading role in the project. Corporations’ internal investments in autonomy could allow them to sell mature technology to the Department of Defense later. (The unit did not grant Undark an interview.) “Working with industry is critical to our success,” said Pahon in an email. “If we want to maintain our technological edge, we have to ensure we’re drawing on the best talent and knowledge that every sector has to offer.”

Corporations are indeed moving forward on development, as Fortem is. Asked if they are applying for Replicator, Robertson, who served two terms in the Utah House of Representatives, hedges. “There’s not a lot known about it,” he said, noting that the company is nevertheless in “close touch” with the Defense Innovation Unit, which is “very aware” of Fortem’s work.

A recent U.S. initiative called Replicator aims to deploy thousands of small, inexpensive uncrewed vehicles: ships, aircraft, and anti-drone devices by August 2025.

Other small companies are also developing their own autonomous technology. One called Saronic, for example, makes small self-directed ocean vessels, on which a weapon or other payload can be placed. (Saronic did not agree to an interview with Undark.)

Big, traditional companies, like Lockheed Martin, are doing the same. While some of Lockheed’s investments in autonomy — which often happen in its experimental division colloquially known as Skunk Works — are developed in direct collaboration with the military, other innovations come from the company’s internal research, so that Lockheed can be ready for future contracts.

Those Lockheed-led research programs involve their own government collaboration. “We’ve been really privileged to have this long-standing relationship, where we get to have really good discussions of ‘What does the government see coming in the future?’” said Renee Pasman, vice president of integrated systems at Skunk Works, because of Lockheed’s history of dealing with the government.

Using the full capabilities of these existing and incoming autonomous weapons could, according to research Riesen published in the Journal of Military Ethics, be seen as part of the military’s duty to soldiers: “The basic idea is that a nation has a moral obligation not to expose its own soldiers to unnecessary lethal risks,” Riesen said. Risks like death, but also of, say, having PTSD — which research suggests soldiers can acquire even from a drone-control terminal in Nevada.

If the military pulled drone pilots and on-the-ground forces farther out of the decision loop, as would happen with autonomous weapons, he said, “then we’re saving our own soldiers not only from lethal risk but also from maybe psychological and moral risk.”

While it’s not clear how the military will think about such risks in the future — and what role its soldiers should have — for startups like Fortem, anticipating what governments may commission in the future can be crucial to their long-term success. And early in the company’s development, it became clear to them that using an autonomous flyer to do drone defense was an area of interest.

Robertson had studied electrical engineering and worked on compact radar systems as part of his master’s degree. Years later, he heard that the radar technology he’d developed was proving useful for a small Army drone and founded a company based on that premise.

“A nation has a moral obligation not to expose its own soldiers to unnecessary lethal risks.”

He co-founded Fortem after that, back in 2016, with an eye towards drone package delivery for, say, Amazon. But soon after starting the company, Robertson wondered about other uses.

Shifting his drones’ algorithm from detecting and avoiding other drones or aircraft — features important for package delivery — to instead detecting and attacking them was almost as simple as switching a plus sign to a minus sign somewhere in the code.

Fortem got a $1.5 million development grant from the Air Force, and its radar system was soon in “chase” rather than “avoid” mode.

Counter-drone systems like Fortem’s align with what the DOD is looking for in its Replicator program, a substantial autonomy initiative in the military at the moment. And the company, as the DOD wanted, did much of the R&D itself, evolving DroneHunter from an off-the-shelf drone and a net made of parts from Home Depot to a custom vehicle with a factory-produced net. Its flight, chase, and capture are autonomous, thanks to that radar system, and play out in the air above Ukraine.

DroneHunter has now been through multiple generations, and thousands of tests behind its own building, next to water like Utah Lake, above farm fields, and at military installations, trying to get the AI system to learn to function in different conditions, and learn crucial differences — for example, how to distinguish a drone from a bird (one has propellers; the other does not). “We can literally test in our backyard,” said Robertson, Fortem’s CTO.

In Fortem’s many tests, the software has also learned to distinguish between threats and innocuous devices: “Is it a drone?” but also “Does the drone belong to a kid taking pictures, or a terrorist?”

Part of that determination involves escalation of force. DroneHunter can warn other aircraft with lights and sirens. If the target doesn’t turn tail but instead approaches, DroneHunter has determined it’s likely to be nefarious. At least, that’s what the device’s AI has learned from cataloged encounters and their associated behavioral patterns.

The company is now developing technology that can destroy an offending drone with munitions, rather than simply capture it, as well as tech that could take out swarms rather than singles.

Many American startups like Fortem aim to ultimately sell their technology to the U.S. Department of Defense because the U.S. has the best-funded military in the world — and so, ample money for contracts — and because it’s relatively simple to sell weapons to one’s own country, or to an ally. Selling their products to other nations does require some administrative work. For instance, in the case of the DroneHunters deployed in Ukraine, Fortem made an agreement with the country directly. The export of the technology, though, had to go through the U.S. Department of State, which is in charge of enforcing policies on what technology can be sold to whom abroad.

The company also markets the DroneHunter commercially — to, say, a cargo-ship operators who want to be safe in contested waters, or stadium owners who want to determine whether a drone flying near the big game belongs to a potential terrorist threat, or a kid who wants to take pictures.

Because Fortem’s technology doesn’t target people and maintains a human as part of the decision-making process, the ethical questions aren’t necessarily about life and death.

In a situation that involves humans, whether an autonomous weapon could accurately tell civilian from combatant, every time all the time, is still an open question. As is whether military leaders would program the weapons to act conservatively, and whether that programming would remain regardless of whose hands a weapon fell into.

A weapon’s makers, after all, aren’t always in control of their creation once it’s out in the world — something the Manhattan Project scientists, many of whom had reservations about the use of nuclear weapons after they developed the atomic bomb, learned the hard way.

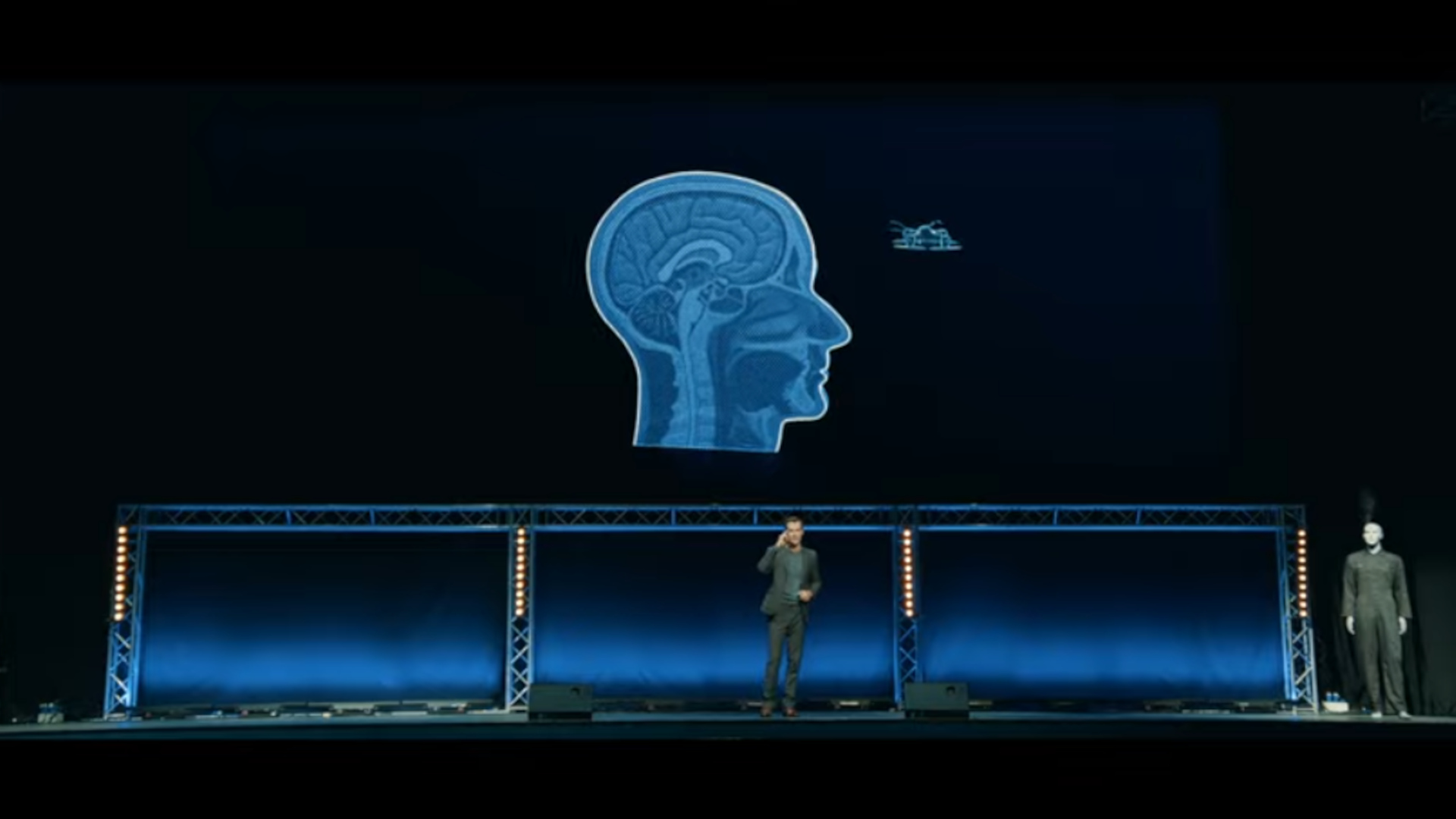

To illustrate this point, the Future of Life Institute — a nonprofit dedicated to reducing risk from powerful technology — created a viral video with the provocative title “Slaughterbots.”

In a situation that involves humans, whether an autonomous weapon could accurately tell civilian from combatant, every time all the time, is still an open question.

“Slaughterbots” opens with a TED Talk-style corporate speech, as a tiny buzzing drone hovers near the speaker: “Inside here is three grams of shaped explosive,” the executive proclaims. The drone then navigates to an onstage dummy, slamming into its forehead with a pop. “That little bang is enough to penetrate the skull,” he says, “and destroy the contents.”

He then shows footage of the drone going after men in a parking garage. “These were all bad guys,” he tells the audience.

The video turns, then, to fictional news footage. The autonomous drones have fallen into the wrong hands; the AI software has been leaked. An automated drone attack kills 11 senators. And then a swarm goes after college kids, killing students en masse.

“Who could have done this?” a newscaster asks an interviewee.

“Anyone,” the interviewee responds.

As Slaughterbots points out, once autonomous lethal technology exists (which it already does, even if it hasn’t yet been confirmed to be employed that way) a well-regulated government might not be the only one to use it — especially if it’s commercial technology available for sale. The potential for the technology to fall into the wrong hands is something that concerns Anna Hehir, the Future of Life Institute’s program manager for autonomous weapons systems.

When Hehir first saw the Slaughterbots video — prior to getting hired by the institute — her first thought was “If these become real, surely they will be illegal straightaway. Surely, the world will recognize this can’t exist.”

The world hadn’t, it turns out: The technology was already in the works, if not fully deployed, and there was no international treaty to deal with it.

Aside from the ethical argument that algorithms simply should not kill humans, legally, Hehir says, autonomous weapons undermine existing international law. “It’s difficult to hold people accountable,” she explained. If a robot commits a war crime, who is responsible? But in the view of Riesen, the Texas A&M philosopher, autonomous weapons shift culpability from a single person — probably a very young adult — to a team of developers, testers, and decisionmakers. “They’re responsible, but there’s a bunch of them,” Riesen said. “So now that risk is spread out to more people.”

Because deploying a swarm of drones is lower stakes than sending a battalion of young soldiers, Hehir said, nations may be more likely to provoke a war, which could ultimately result in more casualties.

Riesen, meanwhile, thinks the opposite. Robots, he said, can be programmed to act conservatively. “We can take our time and say, ‘Is this a combatant? If it’s not, then don’t kill it,’” he said. “Because, hey, if that thing shoots our drone down — whatever, it’s expensive, but it’s not a human. Whereas a death-fearing soldier in that situation is going to shoot first, ask questions later.”

But such programming might not happen if autonomous weapons end up in the wrong hands, act as weapons of mass destruction, and escalate tensions.

The technology was already in the works, if not fully deployed, and there was no international treaty to deal with it.

That escalation could come from robots’ errors. Autonomous systems based on machine learning may develop false or misleading patterns. AI, for instance, has a history of racism, like not being able to differentiate Black people. Facial recognition is also worse at distinguishing women and young adults. That matters always, but especially when the misidentification of civilians versus combatants could lead to lethal mistakes. AI’s decisions could also be opaque from the outside, meaning decisions about life and death are too. Mistakes, like blasting a soldier from a country not yet involved in a conflict, could draw in uninvolved nations, embiggening a battle. “It is still very far from human level intelligence,” said Oren Etzioni, founding CEO at the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence.

It makes mistakes, and those mistakes could involve human lives. “Obviously that’s very worrying in this context,” Etzioni said.

Those kinds of miscalculations could have exponential consequences when, say, multiple drones are involved. “When we’re looking at swarms, we’re looking at a future weapon of mass destruction,” said Kallenborn. And if one of them is prone to making a particular kind of mistake, the other 999 could be too.

The hypothetical escalation that could result relates to another kind of weapon of mass destruction: the nuclear weapon. Some countries interested in autonomy are the same ones that have atomic arsenals. If two nuclear states are in a conflict, and start using autonomous weapons, “it just takes one algorithmic error, or one miscommunication within the same military, to cause an escalating scenario,” said Hehir. And escalation could lead to nuclear catastrophe.

To increase public awareness of autonomous weapons, Hehir has been working on a database of existing arms, called Autonomous Weapons Watch. “It’s to fill this gap of people that say they don’t exist, or this will never happen,” she said.

To find out about new arms, Hehir attends weapons fairs. At these conventions, like Eurosatory, the world’s largest, manufacturers show off their wares, the exhibit floor overrun with cutting-edge tanks and drones. It used to be that when she sidled up to a flashy booth, she said, its proprietor was happy to boast about the technology’s full autonomy. Now, hearing about potential future regulation, she said they keep capabilities quieter. “They want to say there’s always a human in the loop,” she said. And while “a human can just click ‘yes,’” Hehir calls that “nominal human input.”

The database isn’t exhaustive, but so far it contains 17 weapons, five of which come from Anduril and Elbit Systems. “They don’t look like the Terminator,” Hehir said. “They look like drones or submarines.”

Anduril did not reply to a request for comment, and Elbit declined an interview due to “security restrictions.”

The ways that devices like those in Hehir’s database will be used on future battlefields, to what extent, and by whom are pieces of the future known only to the crystal ball. And both human and regulatory challenges present barriers to those weapons’ real-world implementation.

Scholar and soldier Paul Lushenko, for instance, is trying to understand the human operator side of the equation. Lushenko, a former Army intelligence officer and current assistant professor at the U.S Army War College, studies emerging technologies and trust: How much do the people who will be using the weapons trust technologies like military AI?

Paul Lushenko, a former Army intelligence officer and current assistant professor at the U.S Army War College, studies trust in AI technology among those in the military.

Visual: Courtesy of Paul Lushenko

His academic research is driven by issues he’s seen in real-world conflict: The first weaponized drone strike happened in Afghanistan in 2001, just four years before he entered active service, during which he was deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. And he served as an intelligence officer during the era in which drones became a major force of war. As he watched, and was part of, drone strikes, he began to ask questions about how people think about “the rightful use of force,” he said, specifically as it involved drones.

As he began those studies, he realized that the existing research wasn’t as empirically rigorous as he wanted it to be. “They weren’t purporting a theory to test; it wasn’t generalizable; it wasn’t falsifiable,” he said. It was talk. And as a soldier, he wanted the walk too, so he set out to get some data.

The drone research led him to the new technological frontline of AI. Lushenko wanted to know what the people who’d be using military AI — which he calls “the sort of emperor’s new clothes” — thought of it all.

Within the military, he says, there is “an assumption that AI is integral to success on a modern battlefield.” And yet no one up there knew what soldiers thought of the robots they might be partnering with, and whether they trusted them, and why or why not.

The data, as before, didn’t exist. But Lushenko had access that purely academic researchers didn’t: He had the legal authorization to talk to those working at or attending the military and service academies, war colleges, and ROTC programs, as well as the ethical authorization from the relevant institutional review boards that certify human studies.

And so he decided to do survey experiments, in part to suss out generational differences between officers. And there, the surveys had something interesting to say: “Senior officers, so people like me, 20-plus years of service, don’t really trust AI,” he says. But, counterintuitively, in certain instances they express disproportionate (though still middling) support for the military adopting it anyway — a contradiction Lushenko dubs the “trust paradox.”

“Officers are drinking the Kool-Aid or adopting the narrative of their senior leaders: that human-machine teaming on the battlefield, where they give machines greater autonomy to make decisions on life and death, is the way of the future,” he said. If they don’t buy in, Lushenko said, they might be fired. And so they buy in. A challenge, then, is getting higher-ups to dedicate enough resources to ensure the hypothetical weapons are trustworthy, if officers are going to use them regardless.

Junior officers, on the other hand, trust AI more. But they also want human oversight on the technology’s actual operation, and are conservative in their sense of how it should be used. Their individual attitudes about trust and use are also more aligned: More trust, for a given respondent, meant they approved of using it more; less trust meant they approved of using it less. Tellingly, their attitudes also varied more widely than their seniors, suggesting to Lushenko that they haven’t drunk the Kool-Aid (yet).

Lushenko doesn’t believe he’ll be gathering intelligence for a killer robot swarm anytime soon — partly because he thinks the emperor’s new clothes aren’t fully on, and because U.S. policy at this point is that humans must use “appropriate human judgment” over machines’ actions.

He’s right: The U.S.’s plan, according to its Unmanned Systems Roadmap, is to keep humans around, requiring that humans “authorize the use of weapons” — at least for now. A Department of Defense directive updated in 2023 also specifies weapons must behave consistently with the its official ethical principles and responsible AI strategy, and give humans “appropriate levels” of judgment about the use of force. “Our policy for autonomy in weapon systems is clear and well-established: there is always a human responsible for the use of force,” Pahon wrote in an email. “Full stop.”

This recent autonomy directive, says Hehir, has what she called “good” language about things like geographical, spatial, and temporal restrictions on the weapons. “I think the U.S. is making a big effort to talk the talk,” said Hehir.

Within the military, Paul Lushenko says, there is “an assumption that AI is integral to success on a modern battlefield.”

But whether the country walks the walk, she continued, pointing to programs like Replicator, is another question. “It’s very difficult to ascertain how autonomous their systems will be,” she said, echoing other experts’ thoughts on Replicator’s opacity. “But I’m expecting that they’ll be going as close as they can to the limits of fully autonomous.”

Still, talk is something, and Hehir and the Future of Life Institute are working toward international agreements to regulate autonomous arms. The Future of Life Institute and the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots have been lobbying and presenting to the U.N. Future of Life has, for instance, largely pushed for inclusion of autonomous weapons in the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons — an international agreement that entered into force in 1983 to restrict or ban particular kinds of weapons. But that path appears to have petered out. “This is a road to nowhere,” said Hehir. “No new international law has emerged from there for over 20 years.”

And so advocacy groups like hers have moved toward trying for an autonomy-specific treaty — like the ones that exist for chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. This fall, that was a topic for the UN’s General Assembly.

Hehir and Future of Life aren’t advocating for a total ban on all autonomous weapons. “One arm will be prohibitions of the most unpredictable systems that target humans,” she said. “The other arm will be regulating those that can be used safely, with meaningful human control,” she said.

Systems like Fortem’s would fall into that latter category, since the DroneHunter doesn’t target people and keeps a human operator around. And so the hypothetical treaty could allow Fortem to stay in its current business, and require that a person continues to lord over the weapon’s decisions, along with potentially requiring things like transparency into, say, how radar data translates into conclusions about a given target.

It’s easy to think that such regulations are futile: Looking at Hehir’s own database, one could conclude the world is entering an arms race. And Hehir would agree with that. But she sees, in history, times when world powers have slowed such races, as with chemical and biological capabilities. “Over time, military powers realized it just wasn’t in their interest to have these weapons proliferate,” she said. “And they were too risky and unpredictable.”

“Militaries are not stupid,” she added.

But with the current lack of international regulation, nation-states are going ahead with their existing plans. And companies within their borders, like Fortem, are continuing to work on autonomous tech that may not be fully autonomous or lethal at the moment but could be in the future. Ideally, according to Pahon, the Pentagon spokesperson, autonomous technology like the sort behind Replicator will exist more for threat than for use.

“Our goal is always to deter, because competition doesn’t have to turn into conflict,” he said. “Even still, we must have the combat credibility to win if we must fight.”