To Mars and Back: Will NASA’s Ambitious Endeavor Be Worth It?

It Was fall in the Utah desert, and NASA scientist Lindsay Hays was watching the sky. A fat flying saucer soon touched down — a capsule containing bits of an asteroid, which NASA had collected and then shot back home. The capsule’s parachute deployed, slowing its descent toward Earth.

While Hays, deputy program scientist for NASA’s astrobiology program, watched it land, she thought of a different mission — her mission, called Mars Sample Return, or MSR, set to launch later this decade. MSR is an audacious plan to collect samples of material from the red planet and send them on a one-way trip to Earth.

“This is going to be us at some point in the future,” Hays recalled thinking.

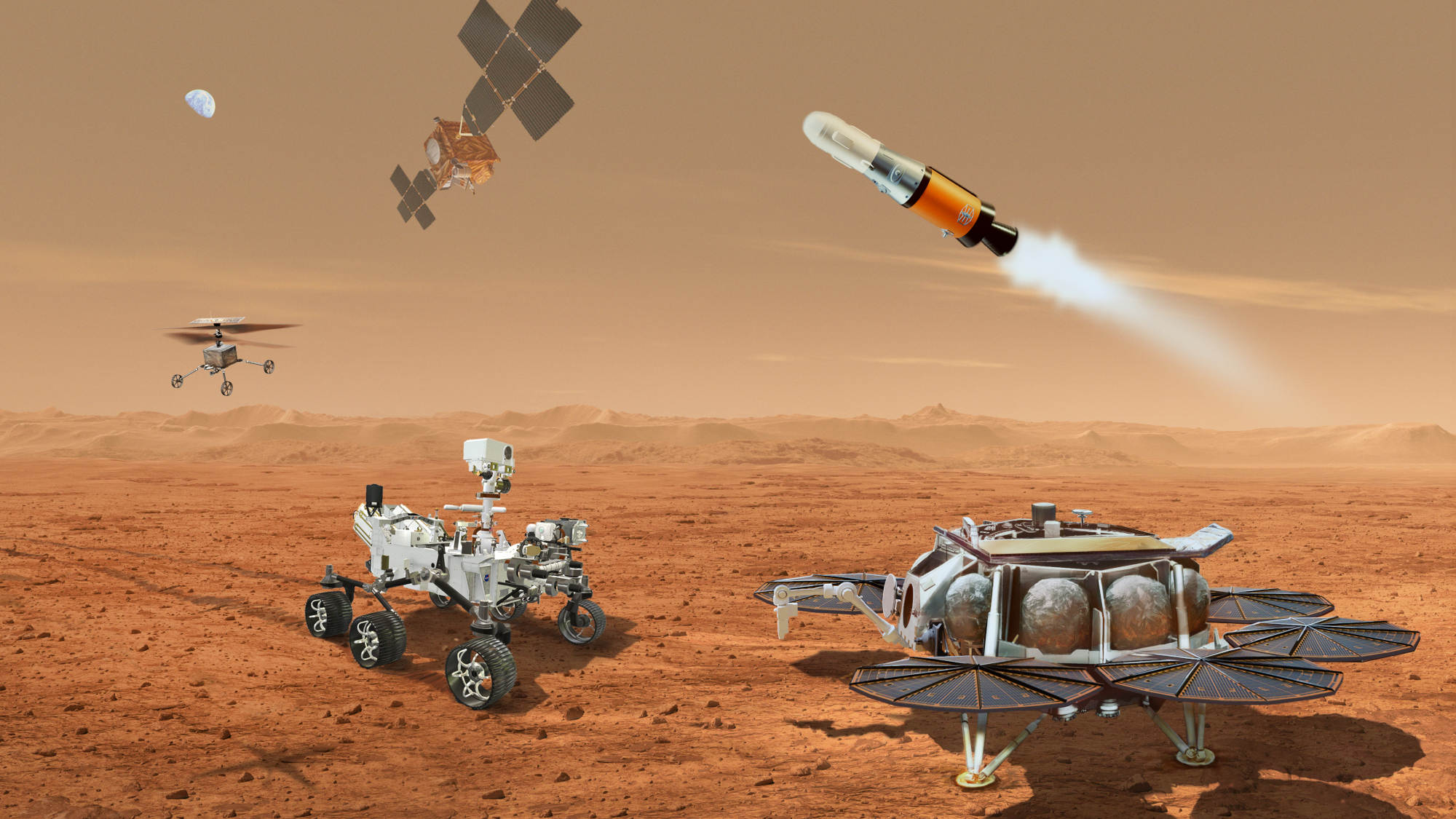

MSR, on which Hays is lead scientist, represents humans’ first attempt to bring material back from another planet. It will also be the first round-trip mission to another planet, and the first rendezvous between spacecraft in orbit around another planet. Scientists hope the project will help them learn about Mars’s past, and how the solar system — and so, obliquely, humans — formed. Analysis could also reveal whether that dead-looking dust-storm of a world was once home to living beings.

“This is not just another planetary science mission,” said Victoria Hamilton, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, a nonprofit science and technology research and development group, and the chair of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group, which provides external scientific analysis that NASA uses to plan its research priorities.

MSR, though, is also hugely expensive, mired in revision and bureaucracy, and, in some experts’ opinions, lacking adequate scientific value. As the planned 2028 launch date approaches, those tensions are becoming more pressing. Budget uncertainties and possible cuts have put the project in limbo as politicians and scientists alike are questioning how MSR’s cost — currently estimated at $8 billion to $11 billion — and scientific benefit balance, and what it might mean for other NASA missions. “They’re competing for funding,” said Linda Billings, who has been a communication consultant for NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office and its astrobiology program. “They’re competing for attention.”

MSR is attention-grabbing, impressive, and has already been appropriated about $1.7 billion for development. It’s also, if it succeeds, a political boon for NASA and the U.S. And so, the program, despite doubts and a current stall, continues, at least for the moment.

MSR has a whiff of the modern, but NASA has been planning versions of the project for decades. “A science community never gives up on a good idea,” said Hays. It’s coming to fruition now in part because the strategy and technology have advanced enough to make it more feasible and because key figures in the planetary science community are ready to pull the trigger.

Each decade, the National Academies of Sciences convenes a representative committee of scientists who work in the field. After soliciting comment from planetary scientists as a whole, they chart out research priorities for the coming 10 years, then write up their analysis in a document called the decadal survey, which charts out the goals and projects deemed most important. The document isn’t gospel, but it does guide funding with a very strong hand. And it is, Hamilton said, “where the buck stops for the scientific community.”

Hamilton was in the field for the previous decadal survey, which put MSR at the top of the to-do list. In 2022, the same was true — for a second decade in a row — with the newest report stating that MSR was “the highest scientific priority of NASA’s robotic exploration efforts,” and should be completed “as soon as is practicably possible.” The document noted, though, that the mission’s cost shouldn’t disrupt the rest of the field.

“This is not just another planetary science mission.”

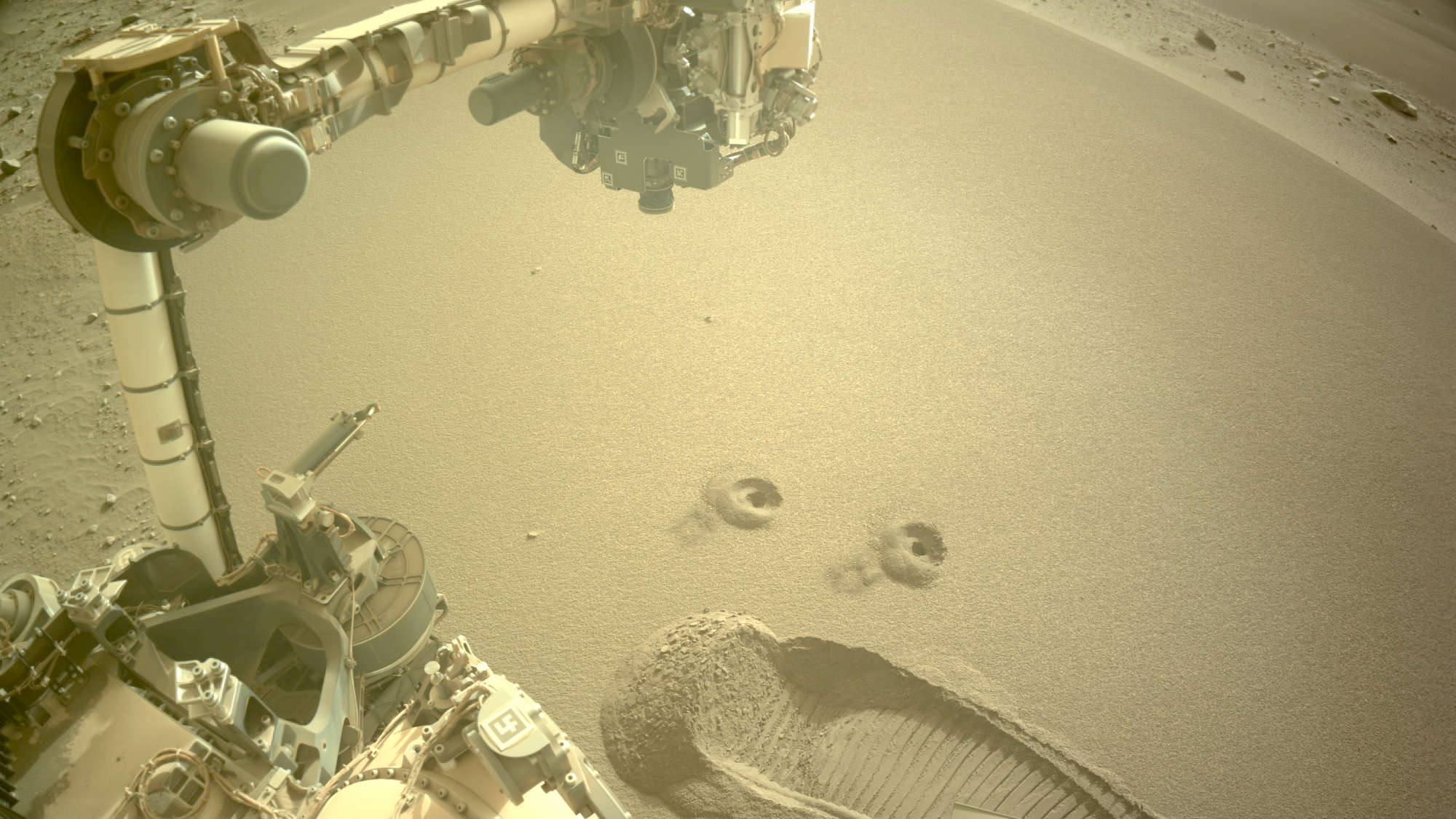

MSR may not yet be completed, but it’s in fact already in progress: Its work began with the Perseverance rover, which has been wheeling around Mars since 2021.

Since it landed, Perseverance has been gathering and storing material to eventually send back to Earth. “We’ve been wanting these samples for decades,” said Amy Williams, a geochemist and astrobiologist at the University of Florida, who works on Perseverance, which is caching samples for MSR.

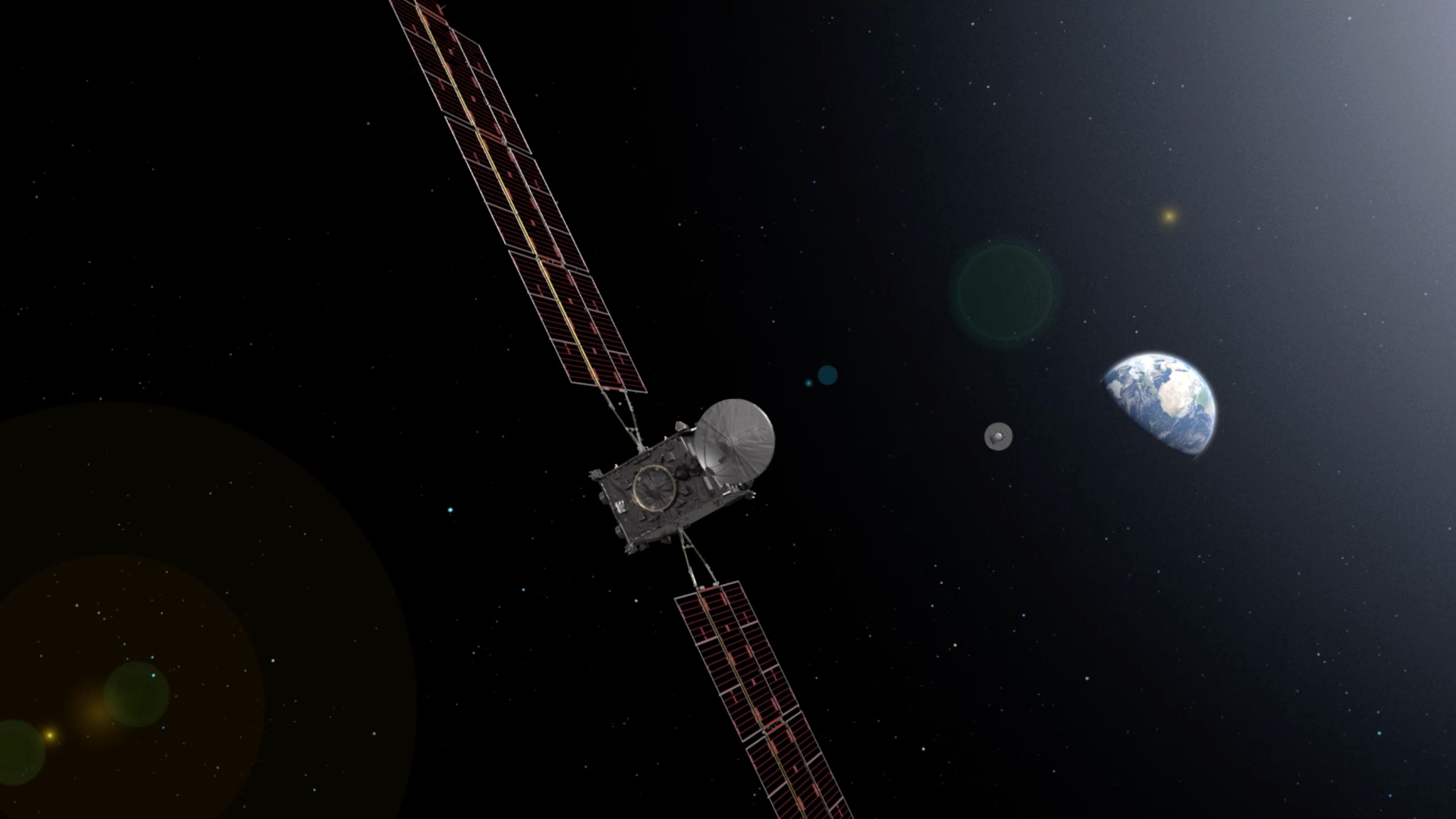

The details, though, are still in flux, as NASA is now rethinking its plans in response to concerns over cost and feasibility. But as the plans stand so far, a rocket will launch from Earth in 2028 or 2030 — when the orbits of Earth and Mars put the planets relatively close together — carrying a robotic lander and a small rocket. Either Perseverance, if it’s still mobile, or two backup helicopters, if it’s not, will shuttle the samples to the rocket, which will launch to Mars orbit. Another spacecraft will then snag the samples and send them to Earth, where they’ll fall to the same Utah desert where Hays watched the saucer drop last year.

Those samples will help scientists understand how Mars formed and evolved, which may give insight into both processes on Earth. And because Mars used to be more like Earth, before it became a scene out of “Mad Max: Fury Road,” studying the red planet’s past, then, might tell scientists something about Earth’s future. “Is this a normal planetary evolution?” asked Williams. “It’s not just about Mars, it really does tie very strongly back to the evolution of Earth,” she continued.

MSR will also search for traces of long-gone life. That possibility is up Williams’s alley; thinking about life elsewhere is what first propelled her cosmic interests. As a kid, she saw a meteor shower while laying out in the back of a pickup truck with her family. “I had this distinct moment where I thought, ‘I wonder if there’s another someone out there looking out into their sky, wondering if they’re alone, too,’” she recalled. Now, “a lot of my work is understanding how life might be preserved on other worlds and how we might be able to detect it,” she said.

Such lofty ambitions come at a steep price — and one that keeps mounting. In April 2023, NASA announced it was convening an independent review board in part to help wrangle MSR’s budget. And in September 2023, its board — which had 16 members, including Hamilton — issued its report.

The authors estimated that the mission may ultimately cost between $8 billion and $11 billion, a far cry from a 2020 independent review that estimated it closer to $4 billion. A new report from the Office of the Inspector General largely concurs with the independent review board’s findings, stating that NASA should have more realistic estimates for MSR’s cost and timeline, and that it should revisit the mission’s specifics.

Given that inflation, the Senate last year proposed slashing the mission’s 2024 budget to $300 million, and possibly canceling it or cutting its scope. (The budget request was for $949 million, a figure the House approved.) The final budget, approved this month gives NASA the option to spend as little as the Senate-suggested $300 million and as much as $949 million on the mission. A report that accompanied the budget noted that NASA must submit its own report on the future of MSR to Congress, after its response to the independent review is complete.

“We’ve been wanting these samples for decades.”

At stake aren’t only taxpayer dollars, but also NASA’s other projects. “Mars Sample Return as it’s conceived is coming at a cost, so to speak — not just inherently, but in terms of what other things we’re sacrificing for it,” said Pascal Lee, a planetary scientist at the SETI Institute, a nonprofit research organization dedicated to understanding life in the universe. “We’re not just paying $10 billion for it. We’re paying even more by not doing other things.”

One such casualty: an international project called Ice Mapper, which aimed to chart out water ice on Mars. NASA withdrew its participation in 2023, citing MSR’s ballooning costs. Another: In 2023, NASA delayed the Near-Earth Object Surveyor telescope — which seeks potentially hazardous asteroids — by two years. And last year, NASA also declared a pause on the Geospace Dynamics Constellation, a mission to study Earth’s atmosphere and the effect of energy from the Sun and nearby space environment on it.

“Unfortunately, sometimes we have budget constraints, and it means that we cannot do everything that we want to do,” said Nicky Fox, associate administrator of NASA’s science mission directorate, during a town hall meeting discussing the agency’s budget. “Some hard decisions have to be made.”

Nicky Fox, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, discusses the agency’s goals during the annual State of NASA address on March 11, 2024.

Visual: Bill Ingalls/NASA

NASA has also delayed the launch of Dragonfly, a plan to send a life-seeking rotored lander to Saturn’s moon Titan — arguably a more habitable spot because of its similarities to Earth — due to budget pressures. “NASA’s Science Mission Directorate looks at the budget as a whole and it is never a one-to-one correspondence where funding one mission directly leads to defunding another one,” NASA public information officer Dewayne Washington wrote in a statement to Undark. “Whenever possible: funding challenges are mitigated within their program lines, so a planetary mission’s budget is not likely to affect one from heliophysics, for example. When we have budget constraints, we seek to ensure a balanced portfolio — aligned with allocated resources and considering decadal survey recommendations. Prioritization is given to: confirmed NASA missions; preserving research funding levels; and minimizing impacts to international partnerships.”

In these contestations, Hamilton, the head of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis group, returns to the decadal survey: It’s a fairly democratic process, and it repeatedly put MSR on top. Still, she emphasizes the survey’s budgetary caveat. “We don’t want to see everything else grind to a halt while this is happening,” she said.

Hays, the lead scientist on MSR, said that NASA is prioritizing the project because it gets at multiple research priorities from the decadal survey, like understanding the origins of the solar system, life and habitability, and how planets function. “You get a lot more out of it than one mission that’s targeted to do one thing,” she said.

The independent committee echoed support for MSR, and its importance to the scientific community. When they published their report last fall, the authors concluded the mission should continue, though they also noted that MSR has a “near zero probability” of launching in 2028 as intended. If the agency wants to launch by 2030, the next window, it can expect to spend more than $1 billion per year between 2025 and 2027.

NASA is currently putting together a response to the review, expected in March. The space agency did not make the MSR’s director, the response team’s leader, or the mission’s new chief engineer available for an interview.

Concerns about MSR value, though, aren’t just about money. Some scientists — including a NASA-funded researcher who studies Mars — question the mission’s scientific value. Lee, the SETI Institute scientist, has spent more than 20 summers running the NASA-supported Haughton Mars project, and said the current plan for MSR isn’t ideal: “In fact, I’ll just say squarely, I’m against it.”

It isn’t that Lee is against MSR’s goals. The life-hunting aspects of MSR are, in his mind, the most important component. “It’s obvious that the question of alien life is the one that would be the most exciting and have the most at stake,” Lee said. According to public agency comments and insights from Hays, NASA agrees with Lee that MSR could be a stepping stone for sending humans to Mars, and that the institution could use MSR to mitigate future money-spending and risk for that endeavor.

The difference, though, is that Lee thinks that, to accomplish those things and justify the costs, MSR should be fundamentally different: The technology could be a more direct testbed for human exploration, using tools more similar to those human astronauts would. And to have a better chance of finding evidence of alien life, says Lee, MSR’s samples would come from deeper or volcanic caves, for instance, where genetic material would be preserved and beings could even still be alive — which would require a distinct approach, including different technology.

“If you’re going to put that kind of money behind it, you really want to optimize what you’re going to get out of it. And to me, we are suboptimal in terms of the science — in fact, weak in terms of the science,” he continued. “For $10 billion, I would want to get more out of it.”

In her time with the Mars analysis group, Hamilton has heard related criticism. “You will find folks who think the scientific objectives are, you know, not bad, but they’re concerned about the fact that you’re only doing sample return from one place on the planet,” she said.

MSR’s samples will all come from the same region. The review board agreed with the need to prioritize variety, even if all the material comes from a constrained area.

Hamilton has also come across another reason some Mars researchers don’t favor the mission: “There are some people who simply aren’t in support of it because it does not benefit their science, to be quite frank,” she said. But Billings, the NASA consultant, questions whether the mission will benefit members of the general public, who are footing the bill. “If you’re not a Mars scientist, who cares?” she said.

Polling, it turns out, back her up. According to a 2023 Pew study, the public believes NASA’s top priorities should be monitoring asteroids and other objects that might hit Earth, and studying the climate — things that aid life on Earth. Several missions NASA is delaying in favor of MSR do, in fact, deal with such terrestrial concerns.

If Billings oversaw NASA’s budget, she said she would focus on science that’s important not just to scientists but to the broader world: “There should be tangible public benefit.”

But MSR’s public benefit may be more political than scientific. The mission is, in the view of the independent review board, an international PR opportunity for NASA, demonstrating “technological expertise and willingness to complete what it sets out to accomplish, no matter how difficult” — a goal the independent review board pulled out as important. “By abandoning return of Mars samples to other nations, the US abandons the preeminent role that JFK ascribed to the scientific exploration of space,” they wrote in their report, calling back to the Apollo era.

Comparing MSR to Apollo is particularly potent at this moment. The dynamics are parallel: China is also planning a sample-return mission, called Tianwen-3. Such competition from an adversary was fuel for NASA during the Cold War, when the agency went up against the Soviets in space. “That was really the reason why we sent people to the Moon,” said Lee. “It wasn’t even about science at all.”

And while science will surely come out of MSR, this mission may owe its continued existence more to political power and international competition — things that tend to resonate with Congress. That is, after all, what appropriators are generally more concerned with, compared to the ages of alien rocks.

“For $10 billion, I would want to get more out of it.”

Today, while NASA retools the mission and fashions a response to the independent review, work on MSR has largely been paused. According to a February press release from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA instructed the lab to plan as if MSR had only the Senate-suggested budget of $300 million while waiting for Congress to agree on a final appropriation number .As a result, the lab announced in the same February press release, it would be cutting around 8 percent of its workforce — more than 500 people — after laying off 100 contractors the previous month. The final 2024 budget told the agency not to lay off any more MSR personnel.

Meanwhile, the cached material sits in tubes on Mars. If they come down to Earth, and what they will bring, though, remain up in the air.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Great article. Informative on what is going on.

To NASA: Every time earth sends a sampler to a planet, it should leave behind a signal booster for planet to planet communication.

To Editor: Typo

The final 2024 budget told the agency not to lay of any more MSR personnel. IT SHOULD READ not to lay off any more MSR personnel.