The Toxic Sands Threatening Fish in Lake Superior

Chris Peterson reels in a net from the side of his fishing tug as it glides along Lake Superior, on the western edge of Keweenaw Peninsula. The skies are gray, and the warm air smells like rain. Wearing orange waders and a knit cap, Peterson stands 6-foot-1, a cigarette dangling from his lips.

He shouts to be heard over the loud drone of the engine. “Save him,” he yells to a deck hand, who untangles a wiggling lake trout from the net. Crying seagulls trail the boat, waiting to feed on the innards they know will go overboard. The fishermen end up pulling in about a hundred pounds of fish from the cold water — not a bad catch for a couple of hours of work, they say.

But about 25 miles away on the east side of the peninsula, a dark beach sits strangely quiet. Though it’s early summer, there are no sounds of singing birds or other wildlife. The sand is metallic-brown, and crumbly so that it sinks underfoot.

Located in the rugged Upper Peninsula of Michigan, the beach forms part of a massive mining waste site that has festered for decades in a region known as “Copper Country.” The sand is a waste byproduct called “stamp sand” — crushed ore, left behind from copper mined a century ago or more. By some estimates, about half a billion tons of these tailings were deposited in and along Lake Superior, the planet’s largest freshwater lake by surface area. And now the toxic sands are pushing their way onto a sensitive fish spawning ground called Buffalo Reef.

The reef is the birthplace of almost a quarter of southern Lake Superior’s commercial catch of lake trout and whitefish, staple foods for local Ojibwe, and highly valuable to the region’s fisheries. According to one 2019 report, it’s estimated to be worth nearly $4.9 million a year to the regional economy.

Though it’s early summer, there are no sounds of singing birds or other wildlife. The sand is metallic-brown, and crumbly so that it sinks underfoot.

Peterson is a fifth-generation commercial fisherman working on Lake Superior — called Gitche Gumee, or “big sea” in the Ojibwe language — and a member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. But he avoids setting his nets down at Buffalo Reef. “I don’t even fish there no more,” he said, because there are no fish left to catch. “None.”

By 2025, researchers predict 60 percent of the reef will no longer be viable for spawning, and scientists are now working with the tribes, as well as state and federal agencies, to prevent its total loss — even as new mining interests loom. The sheer scale of the sands — about 25 million tons of copper-laced mine tailings — have proven to be a high hurdle for existing clean-up efforts. But stakeholders are hoping a new, multi-year cleanup plan, which could cost upwards of $1 billion, will help to address the slow-moving tide of mining waste.

The Lake Superior Ojibwe maintained control of the Keweenaw Peninsula until the mid-19th century, when geologists began to identify huge deposits of iron and copper, said Carol MacLennan, an anthropologist who studies mining history and pollution. “Americans really became very interested in the copper deposits, in particular, and wanted to acquire the land the copper was on,” she said.

An 1842 treaty ceded these metal-laden lands to the United States. In exchange, tribes maintained their right to hunt, fish, and gather. The mines of the region produced some 14 billion pounds of the metal, dug from the largest native copper reserve ever unearthed. Unlike other copper deposits, which can be mixed with other metals, such as silver, native copper is unadulterated. The highly conductive metal supplied the raw goods for electrical wires and telephone lines, helping fuel American expansion.

“I don’t even fish there no more,” Chris Peterson said, because there are no fish left to catch. “None.”

By the turn of the century, the Wolverine and Mohawk mines loomed large in the region. At mills in Gay, Michigan, they parted copper from ore in a process called jigging, a crude separation method using gravity and copious amounts of lake water. The leftover tailings were then pushed along conveyors into Lake Superior, where they laid exposed to the elements.

Today, about half of the sands remain onshore and half lay underwater, where they’re moving south toward Buffalo Reef.

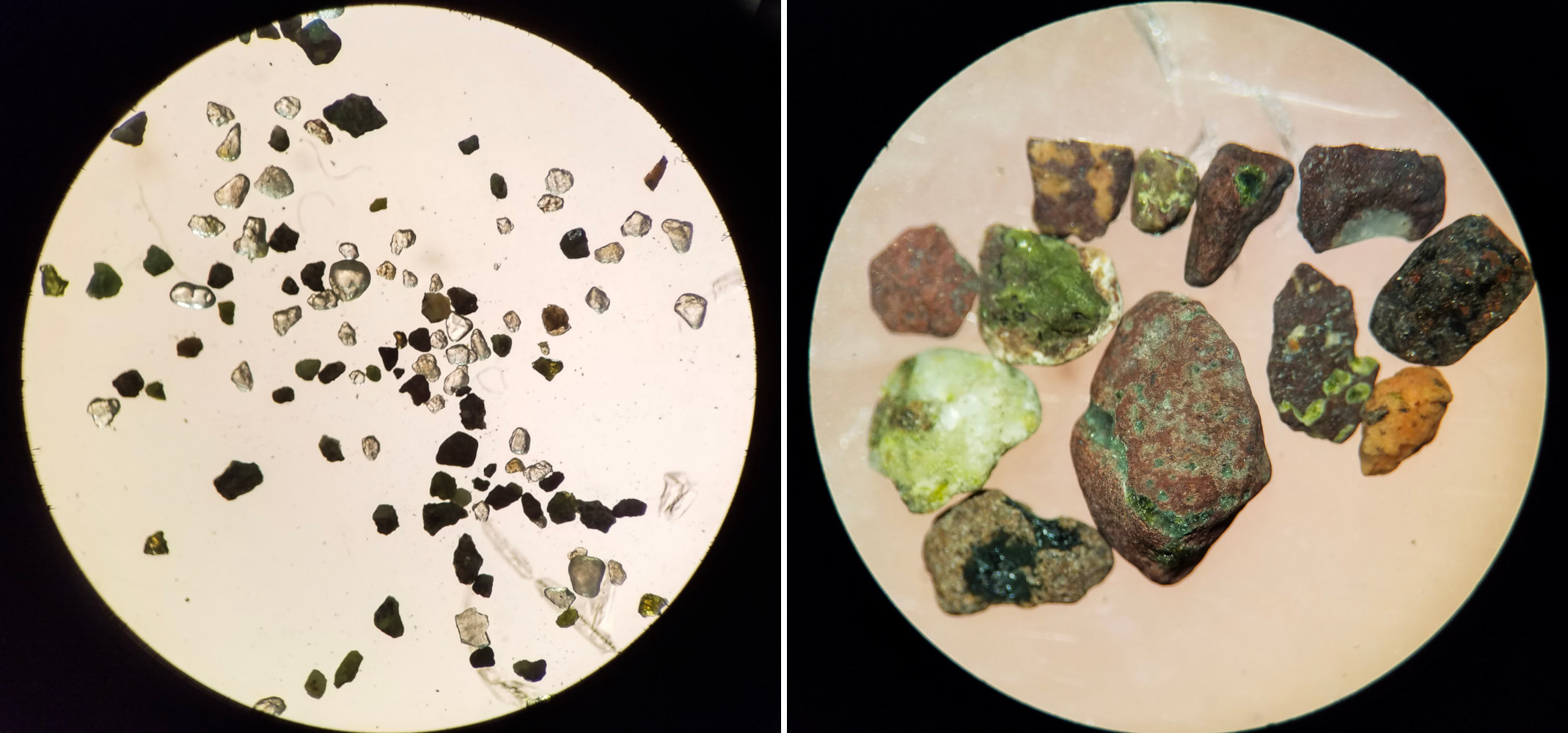

Charles Kerfoot, an ecologist at the Great Lakes Research Center, has spent the past 15 years studying how the stamp sands affect the reef. At his lab at Michigan Technological University in June, he bent forward and peered into a microscope to look at a sample. There are bright-colored rocks and minerals; lime-colored epidote, sea-green pumpellyite, and jagged pieces of volcanic-black basalt.

And there is copper. “The tailings are very enriched in copper,” said Kerfoot, who has measured between 0.2 and 0.3 percent copper in sand from the waste site. “If it were 0.8 percent, it would be a mineable deposit.”

The sands also contain arsenic and lead, known carcinogens, along with harmful mercury. All three metals build up in food webs that support fish, which can pose serious health risks when consumed by humans. “They could potentially come back and haunt us, even if in modest concentrations,” Kerfoot said.

In a 2021 study published in the journal Remote Sensing, Kerfoot and a team of researchers found the sands were highly toxic to the reef’s benthic organisms — creatures that live at the bottom of the lake and serve as important food sources for the lake trout and whitefish.

Using LiDAR, a method that uses laser pulses to measure distances, the study revealed an absence of benthic animals where stamp sands were most dense in the sediment. “When you reach 50 percent stamp sands, you’re down to maybe a third of the density,” said Kerfoot. “When you go up to 75 percent, there’s almost nothing there. It’s a desert from 75 percent on out.”

Under normal circumstances, he said, the reef would contain thousands of these organisms.

“The fish on the reef — lake trout and lake whitefish, chinamekos and adikameg — use the reef to spawn,” explained Bill Mattes, the Great Lakes section leader at the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, or GLIFWC, an agency that represents 11 Ojibwe tribes that retain off-reservation treaty rights. “The eggs go down into the interstitial spaces between the rocks, the small areas between the rocks where they incubate. The wind and wave action provides oxygen to the eggs while they’re down there developing.”

But the finest sands are filling in those spaces, Mattes said, and these sands contain copper. “Copper gives off an electrical charge,” he said. “Fish can pick up that electrical charge with their lateral lines, their sensory systems. So, they tend to steer away from high levels of copper.”

Despite this, said Mattes, the fish continue to spawn at the reef — though with less reproductive success. After fertilized eggs incubate, they hatch and enter the water column, where they’re at the mercy of the currents. “As the shoreline is being covered with the stamp sands, they need to move. They need be drifted further and further before they actually find food,” Mattes said.

In 2021, as part of an ongoing project to monitor the health of the reef eggs, scientists from GLIFWC and the U.S. Geological Survey collected fish embryos and then exposed them to varying levels of stamp sands. After careful monitoring, both lake trout and lake whitefish were found to be adversely affected by the sands.

“When you get above 30 percent stamp sand, you see less than half of your embryos successfully hatching,” said Mike Lowe, a fish biologist with USGS. At 60 percent stamp sands or higher, hatching success dropped to 10 to 15 percent for the lake whitefish, he said.

Overall, the effects were more pronounced in the lake whitefish. “Whitefish do tend to be more sensitive,” Lowe said, preferring to stay closer to shore. “It appears that their spawning habitats have shifted offshore into deeper waters.”

Meanwhile, LiDAR data reveals storms are hastening movement of the sands onto the reef. That season, a severe storm came through, destroying all but a handful of egg traps set out for Lowe’s research. And these storms have become more forceful and frequent in recent years, Peterson said, limiting the number of days that it’s safe to fish on the lake. Storms, he said, are “what’s moving all of that sand.”

On a quiet summer morning, the tugboat “Spirit” sits motionless on glassy, sun-streaked water in Grand Traverse Harbor, less than a mile away from Buffalo Reef. Later, the boat will head out onto the lake to net fish, traveling along a curving breakwall on the way to open water.

Michael Peterson is Chris Peterson’s cousin and captain of the Spirit. He keeps his boat docked in the harbor, next to where he lives, and has taken scientists, such as Lowe, out on the lake to do their research. The sands have turned the once sugary beach in front his home to gunmetal gray. “The state should have stepped in a lot sooner,” the fisherman said.

Alarmed by the sands headed toward the reef, it was Peterson’s father, the late Cecil Peterson, who first brought the problem of the stamp sands to the state’s attention in the late 1980s.

In 2003, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredged the harbor, removing stamp sands along the shore in the process; two years later, GLIFWC carried out a mapping project to assess the sands at the reef. And in 2017, the EPA formed the Buffalo Reef Task Force, a group from agencies including the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, which aimed to find a long-term fix for the sands, and funding to pay for it. As part of its work, the task force relied on research by Lowe, Kerfoot, and other scientists, to better understand how mining waste affects the lake’s ecosystem.

Later that year, the state dredged sands that were mounting the north side of the breakwall and filling in Grand Traverse Harbor. But in the weeks that followed, a violent storm pushed the sands back to where they had been, topping the breakwall and filling the harbor. “That thing just came across like a snow drift,” Michael Peterson said.

Decades after Cecil Peterson’s warning, it seemed the sands were gaining ground.

Since then, numerous efforts have been undertaken to protect Buffalo Reef: In 2019, the EPA provided $3.7 million to support more dredging. Over the next few years, the Army Corps removed the sands from an underwater trench spilling sands onto the reef and the state’s contractor removed a 30-foot bluff of sands eroding into the lake. And through a grant from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community funded work to pull yet more stamp sands away from the harbor breakwater and return them to the shore in Gay. The work is ongoing.

Dredging projects have been carried out every year since, including further south, on the KBIC reservation where Kerfoot, MacLennan, and other scientists have turned their attention to another stamp sand site — polluted by yet another copper mine — home to wetlands and important cultural grounds.

Copper isn’t the only metal embedded in the rocks of the Upper Peninsula: They also contain vast deposits of iron and nickel — which, like copper, are sought for making batteries used in electric vehicles. Nickel is also among the country’s “critical minerals” deemed essential for clean energy technologies. And as scientists, tribes, and government agencies reckon with the century-old waste threatening Buffalo Reef, mines continue to operate in the region.

Over its life from 2014 to 2027, Eagle Mine — located about 30 miles from the KBIC reservation — is expected to churn out 440 million pounds of nickel and 429 million pounds of copper. That will likely supply much of the nickel needed to support the Biden administration’s plan to make half of all new vehicles sold in the U.S. electric by 2030, and shift the country’s reliance for EV technology away from China.

But in a region tainted by the legacy of mining, residents are wary of the polluting effects of mining, particularly where there is water.

Specifically, the Eagle Mine extracts sulfide ore, which, when exposed to water and air, produces sulfuric acid runoff. This runoff can, without proper mitigation, pollute drinking water, corrode infrastructure, and harm fish and other aquatic life. Lundin Mining, the company that owns the Eagle Mine, says environmental risks from the mine are mitigated by state-of-the-art technology that filters water to regulatory standards.

Lundin isn’t the only company digging the region’s prized metals. In northern Minnesota, Talon Metals has agreed to supply Tesla with nickel from the Tamarack mine, and NewRange Copper Nickel has proposed a copper-nickel mine in the Duluth Complex — though a key permit was revoked in June after it was challenged by the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. Both are sulfide mines located near Ojibwe lands.

In a region tainted by the legacy of mining, residents are wary of the polluting effects of mining, particularly where there is water.

“Our treaty rights to hunt, fish and gather in perpetuity are just as important as the non-Indians’ rights to hunt, fish, gather and use the environment,” said Frank Bibeau, a Minnesota Chippewa Tribe member and an attorney focused on Rights of Nature. “The problem is we’re Indians,” he said. “Historically, we haven’t had our rights respected or enforced by the federal government.”

The Biden administration recently proposed reforms to the more than 150-year-old federal mining law. “The real problem is we don’t have any kind of federal underlying law that requires basic standards for opening a mine — that means permitting it and making sure it’s safe and the technology is adequate,” MacLennan, the anthropologist said.

Though many of the new mines have shorter lifespans than legacy mines of the Keweenaw, she added, “They’re lasting in their effects.”

The work continues at Buffalo Reef. A multi-year cleanup plan includes building a 2,000-foot jetty to block further intrusion, more dredging of the underwater trench, and removal of shore sands to a nearby landfill. The original waste pile is slated for removal by 2040.

The endeavor will be expensive, said Mattes, but he plans to keep pushing for federal and state funding for more cleanup. The research, carried out by Kerfoot and others, provides the evidence needed to show the extent of the damage caused by the sands, Mattes said. “If we don’t clean this up, it’s going to continue to be a problem,” he said. “And the problem that it causes is going to be worse over time.”

Already, the sands have been used as a replacement for road sand. Researchers are developing their use in concrete and as moss-repellant in roofing shingles. Mattes thinks there may be more uses for the copper-rich sands in the future. “The copper that was mined from the Keweenaw Peninsula, we still use in our electrical grids today,” he said.

“The problem is we’re Indians. Historically, we haven’t had our rights respected or enforced by the federal government.”

But the region has paid for what was left behind. Mattes thinks this is, in part, because, like so many mining sites, the Keweenaw mines were located in a remote, sparsely developed area. “If these stamp sands were on the shore next to a big city where there were people wanting to develop the shoreline for condominiums, it would’ve been gone a long time ago,” he said.

The warnings of an Indigenous fisherman were the catalyst for the cleanup of the reef, Mattes points out. “Going back to the very beginning, it was the environmental knowledge of the tribal commercial fishermen that set this whole thing in motion,” he said.

It comes down to a question of whether mining companies can act more responsibly when extracting the world’s natural resources, Mattes said. “I think we can do things differently.”

Shantal Riley is an award-winning health and environmental reporter, focused on water quality in communities of color. Her work has been featured by Frontline PBS, NOVA PBS, the Washington Post Magazine, and other publications.

This story was supported in part by The Uproot Project, which is operationally and financially supported by Grist.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Another reason to not support EV production. The wildlife and fish can’t survive – are we far behind?

The DNR is dumping poison in lakes in the woods they are spraying Roundup in every clear cut I have found death ☠️ in the woods where they sprayed my dog was catching baby ruffled grouse that they have no feathers and can’t fly dead porcupines dead raccoons two deer that were dead with all their hair falling off them wonder what else it killed snakes toads the list goes on

The Trout Don’t Even Get A Chance to Spawn.

These Indians Have Taking All The German Brown Trout Gill Netted Killing Fish, There’s No Fish Because The Indians Have Killed The Trout,Ban These Gill Net Killers In One Day Indian Killers Gill Netted 450 Plus Lake Trout,And Indians Are Liars They Run Over 10 Mile Long Gill Nets STOP The Gill Nets STOP The Indians The Trout Don’t Even Get A Chance To Spawn.. STOP THE FISH KILLERS…