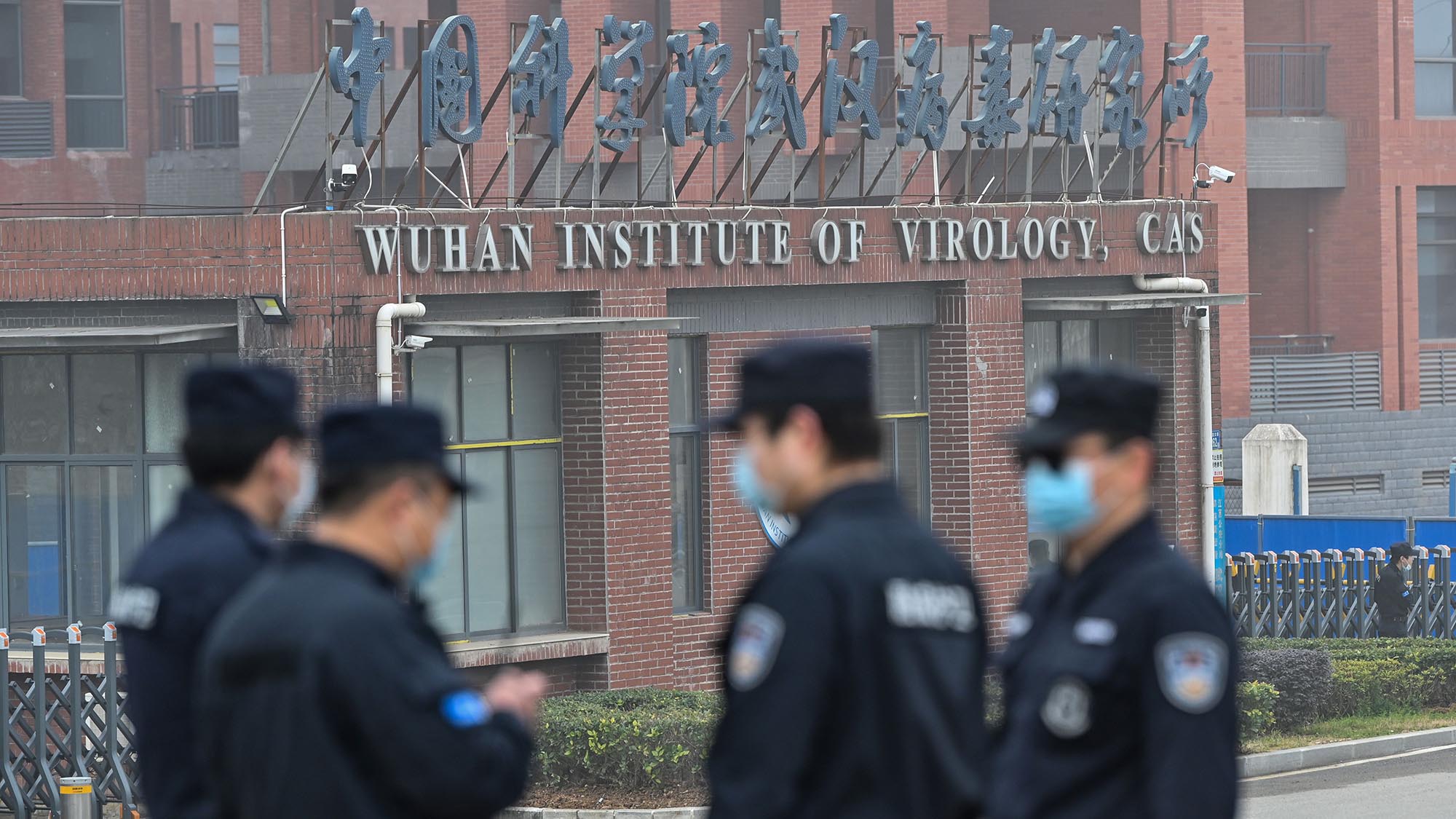

The origin of Covid-19 remains a subject of intense public interest, and it hinges on two main hypotheses: One holds that the virus developed naturally among wild animals and spilled over into people, most likely through a wildlife market in Wuhan, China. The other posits that the virus came by way of an accidental exposure during fieldwork or a leak from a virology lab in the same city, known for conducting extensive and, many say, risky experiments on novel coronaviruses from wild animals.

Figuring out which hypothesis is true is of utmost importance, given the pandemic’s toll. The U.S. alone has suffered more than a million Covid-19 deaths and hundreds of millions of infections, leaving many struggling with long Covid and pandemic-related mental health problems. Experts have estimated that Covid-19 will cost the U.S. $16 trillion — nearly half of its national debt for context. In light of all this, one would expect an army of investigative journalists to be digging for the truth, and a bipartisan commission with subpoena powers to be in full force to find the origin of Covid-19.

To date, neither have really happened. The New York Times reported last year that the White House privately opposed forming such a commission despite appeals by Democratic Sen. Patty Murray. And this year, the Director of National Intelligence failed to release classified intelligence potentially linking the Wuhan Institute of Virology to the origin of Covid-19 — in spite of a bill passed unanimously in both the Senate and House and signed into law by President Biden. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, a Republican from Washington and the House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair, called this “a slap in the face of Americans who deserve full transparency about what information the government possesses regarding the origins of COVID-19.”

China’s refusal to allow access to the Wuhan laboratory and other key pieces of information has made a full investigation nearly impossible. However, the coronavirus research in Wuhan was part of a U.S.-China collaboration, suggesting that there are tranches of evidence to be explored here at home. And yet, as journalist Katherine Eban recently wrote on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter, most news outlets have avoided truly digging into this evidence.

“The story is toxic to most news outlets due to (false) claims that it’s somehow right-wing/anti-science to investigate how upwards of 10-million people died,” wrote Eban, who is among the few journalists who have given the lab leak hypothesis a serious look. “Only a small band of journos continues to actually report.”

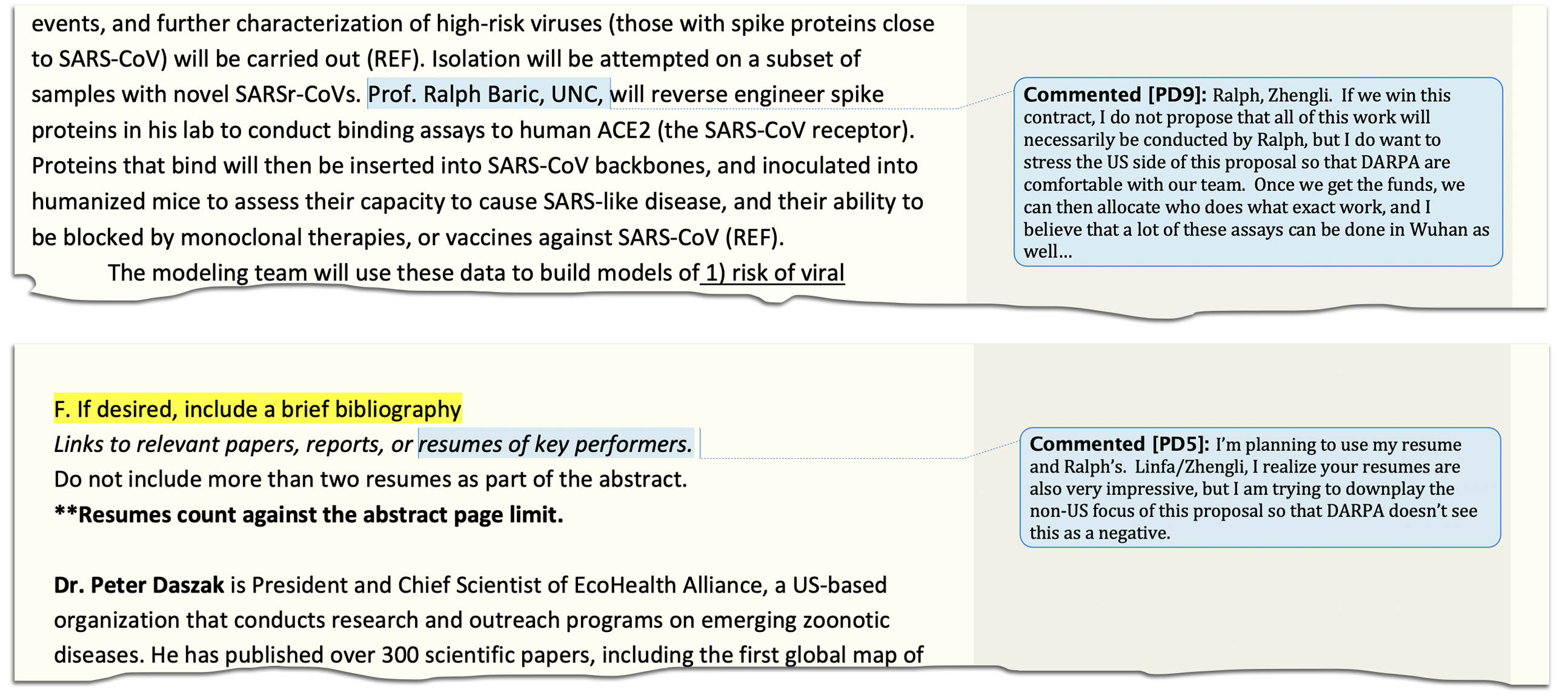

Most notably, in 2021, a group of amateur online sleuths known at the time as Drastic obtained a research proposal written by U.S. and Wuhan scientists and submitted to a Department of Defense agency in 2018. The proposal detailed plans to grow or synthesize novel SARS-like coronaviruses from bats, and to test these on human airway cells and humanized mice — models for human SARS infection. The proposal shows that the scientists specifically wanted to bring novel SARS-like coronaviruses collected in nature back to the lab and insert a feature called a furin cleavage site, which could alter — and even enhance — a virus’ ability to transmit across species and cause disease.

The Defense Department ultimately rejected that proposal, but the SARS-CoV-2 virus that emerged in Wuhan in late 2019 possessed just such a furin cleavage site — a feature so far not observed in other SARS-like viruses found in nature. To a skeptical observer, it was as if these scientists proposed to put horns on horses and not two years later a unicorn showed up in their city.

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive.

A natural question is whether the Wuhan scientists undertook any of this work on their own despite the funding rejection from the U.S. Defense Department, and if so, whether their U.S. counterparts worried, or even knew, that this was the case. Despite all this, the leak of the 2018 proposal — a significant development — was largely ignored by most major news outlets. And we have yet to see any formal government investigation compel these U.S. scientists to hand over all communications and documents exchanged with Wuhan scientists.

Instead, a small band of determined sleuths, scientists, and journalists have been left to chip away at one of the biggest stories — and scientific mysteries — of the modern era. Most recently, an organization known as U.S. Right to Know released earlier drafts of the failed 2018 proposal, which they obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests. These documents seemed to reveal that U.S. investigators were, indeed, planning to delegate some virus engineering experiments to the Wuhan lab — a detail that does not seem to have been included in the final Defense Department proposal.

The U.S. researchers have since responded to the release of these new draft documents, calling the interpretations misleading. And some critics have dismissed USRTK as being driven by an anti-science agenda. But even if that were true, the public should have long ago been afforded an opportunity to review such crucial documents for themselves, raising the question of why, as we enter the fifth year of the Covid-19 era, no other organizations — not The New York Times, not CNN, no Congressional investigator or empaneled commission — managed to dig up these documents sooner.

Instead, it has been outlets like the Intercept, Eban writing at Vanity Fair, and the activists at USRTK, who have turned up a steady drip of revelations about risky experiments and uncanny coincidences. Have they proven that the virus came from a lab? No. But imagine if the lab leak theory had not been so quickly dismissed by influential scientists in 2020, and subsequently given short shrift by many in the media — including, early on, this one. Leading journalists and formal investigators might have rapidly unearthed everything that we know today, and likely much more.

As it stands, the stunning lack of curiosity among mainstream journalists and scientists, as well as many government officials, stands in stark contrast to public opinion. Polls this year found that a significant number of people around the world — and a majority of both Democrats and Republicans in the U.S. — believe the pandemic virus likely originated from a laboratory in China. This view is also supported by assessments from two U.S. intelligence agencies, staffed with some of the nation’s the top scientists.

But it is shocking that we still do not have access, among other things, to communications and documents that would help put the matter to rest — including those exchanged between the Wuhan scientists and their U.S. collaborators before and during the Covid-19 pandemic. China may have blocked meaningful access to ground zero, but critical sources of evidence are conceivably within the reach of U.S. investigators and journalists — if only they would try.

Alina Chan is co-author of Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19, scientific adviser at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and a member of the Pathogens Project task force organized by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Scientists deal in testable hypotheses. In this piece Chan fails to describe a single hypothesis that can be supported or falsified by any “communications and documents that would help put the matter to rest.” In failing to do this, she reveals that new documents would not, in fact, help put the matter to rest. The proof of this is demonstrated in this very article: what was put to rest by seeing drafts and comments related to this research proposal? Instead, all we get are another set of questions based on bad interpretations of comments cherry picked and taken out of context.

I encourage readers to think like a scientist when considering the evidence presented (and consider that links to DOE and FBI website are not evidence). Consider the appeal to a cleavage site: Chan helped develop an online tool tracking SARS2 evolution during the pandemic and is plainly aware of the frequency of short inserts acquired by SARS2 genomes. Nearly every one of these is “a feature so far not observed in other SARS-like viruses found in nature.” All of them occurred naturally. It’s the God-of-the-gaps and the gap is miniscule; sequences similar to SARS2 near this site are very sparsely sampled. Of the very few samples similar to SARS2 *around* this cleavage site (so far, none are identical), one happens to have been found not in a bat, but instead in the wildlife trafficking industry. However, it appears that eerie coincidences only count as evidence if they point in one direction.

The scientific method is not well suited to resolving the question of whether covid originated from a lab leak. What is really required is a multidisciplinary forensic investigation informed by virology, epidemiology, statistics, politics and other fields. And a starting point of any sound investigation is an open mind.

Sure. Let’s consider some aspects beyond biology.

Chan complains that lab leak was “given short shrift by many in the media” and links to an article titled “Covid-19 origins: A media conspiracy of silence” which primarily focuses on why Nicolas Wade got turned down by NYT, WSJ, and the Economist. But the piece Wade was selling is perhaps the silliest example of Intelligent Design literature you’ll ever read if you approach it with an open mind.

An open mind would consider evidence that Chan excludes. Did you know that a SARS2-like virus was grown in a lab prior to the SARS2 outbreak? That happened in Nanjing and would be the eerie coincidence of choice cited to promote a lab leak theory had the pandemic started in Nanjing. Did you know that one of the viruses most closely related to SARS2 was sampled in pangolins in Guangdong? So add Guangzhou to the list of eerie coincidences in alternative timelines as well. This goes on and it’s worth considering with an open mind because once you get past the seemingly eerie coincidence all you are left with is motivated reading between the lines of emails and unfunded grant proposals rather than evidence.

Excellent work on this Alina. The answer to your very valid question is that there are many people in high ranking positions that have a vested interest in not knowing the truth. While the truth would enlighten us it would likely work against their interests.