The Global Climate Fallout of Australia’s Massive Wildfires

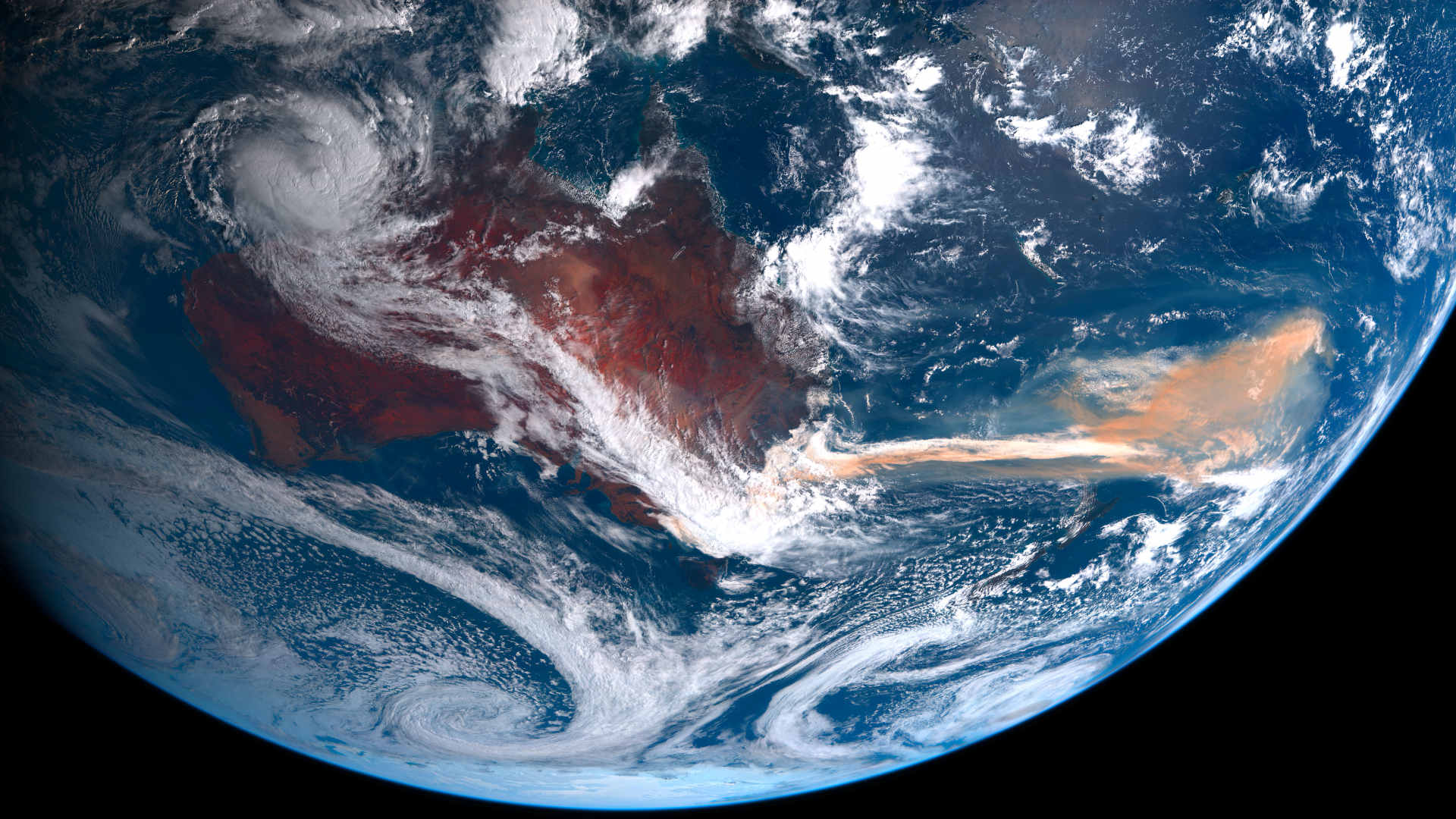

The aerosol fallout from wildfires that burned across more than 70,000 square miles of Australia in 2019 and 2020 was so persistent and widespread that it brightened a vast area of clouds above the subtropical Pacific Ocean.

Beneath those clouds, the ocean surface and the atmosphere cooled, shifting a key tropical rainfall belt northward and nudging the Equatorial Pacific toward an unexpected and long-lasting cool phase of the La Niña-El Niño cycle, according to research published last week in Science Advances.

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Aerosols from wildfires are basically fire dust — microscopic bits of charred mineral or organic matter that can ride super-heated wildfire clouds up to the stratosphere and spread across hemispheres with varied climatic effects, depending where they’re produced and where they end up.

In the new modeling study, the scientists quantified how aerosols from the Australian wildfires made clouds over the tropical Pacific reflect more sunlight back toward space. The cooling effect was equivalent to switching off a 3-watt light bulb over every square meter of the ocean region. And that cooling, their data showed, shifted the cloud and rain belt called the Intertropical Convergence Zone northward.

Combined, the effects may have helped trigger the rare three-year La Niña, from late 2019 through 2022. The impacts of the La Niña rippled around the world, intensifying drought and famine in Eastern Africa, and priming the Atlantic Ocean region for hurricanes, as 2020 became the most active tropical storm season on record with 31 tropical and subtropical systems, including 11 storms that made landfall in the U.S., including four alone in Louisiana.

“The findings highlight widespread multi-year climate impacts caused by an unprecedented wildfire season,” said lead author John Fasullo, an atmospheric scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado.

“From November through January, massive amounts of smoke were pumping continually into the atmosphere,” he said. “The more particulates you have in the atmosphere, the more cloud droplets you get, the brighter those cloud droplets are, and the longer they live in the atmosphere. These stratus cloud decks are so important for Earth’s energy budget that if you’re able to perturb them a little bit, it makes a big difference.”

Such large-scale interactions between wildfire aerosols and the climate “may become more prevalent under climate change as wildfires are projected to intensify and become more frequent,” the authors warned.

The new paper fits together with other recent research on how global warming affects ocean currents in the Southern Ocean, said NCAR climate scientist Stephen Yeager, who was not involved in the new study.

“The link to climate change is kind of hidden in there,” Yeager said. “The wildfires set off this chain of events that lead to cooling in the eastern Pacific. It’s a chain reaction that we can expect more of in the future,” he said, “because we expect wildfire emissions to go up. We expect Australia to get drier and for these wildfires to get worse.”

Yeager said the new research is valuable because it highlights how ecosystem changes and disruptions on land can affect the ocean and atmosphere.

“This interaction wasn’t fully appreciated,” he said. “Climate dynamicists are traditionally interested in the atmosphere in the ocean and how they interact. But adding land to the mix through this wildfire forcing is pretty novel. I think it does, at the very least, show that the climate system is so interconnected, that you can’t intervene in one place without affecting the evolution of climate in other places.”

Fasullo said the research could also make seasonal projections for El Niño and La Niña episodes more accurate, which is important because both phases of the Pacific Ocean cycle have extreme climate impacts in different regions and different seasons. The effects of the smoke documented by the study show how an extreme event on land can kick the climate system into a different state, he added.

“You have a couple of things here,” he said. “First, is that typically La Niña follows El Niño, but this is an example of a La Niña event that had no preceding El Niño. That’s not completely impossible, but unlikely. The second thing is, we had this La Niña event that lasted for three years that didn’t follow an El Niño. That is unprecedented. Previous long-lasting La Niñas have always happened after a strong El Niño.”

In the El Niño-La Niña cycle, the equatorial Pacific Ocean alternates between warmer and cooler conditions about every three to seven years, with somewhat predictable effects on storm tracks and precipitation patterns and associated extremes.

Those two things are unique and suggest that something like the Australian wildfires were critical to triggering the La Niña in late 2019, he said, adding that federal climate experts were caught off guard by its sudden emergence and intensity. In the future, calculating the added influence of wildfire smoke could enable an earlier and more accurate forecast, giving communities more time to prepare for impacts.

“I’m not sure NOAA likes to be called out for the fact that they had a neutral forecast in June of 2020,” Fasullo said. “I kind of think one of our reviewers of the paper was from NOAA. And he objected to that statement. But I stand by it. I’ve got a screen capture of their website, and they keep the archive of all predictions online, so you can go back and look.”

Both Fasullo and Yeager said the findings could also have implications for any future proposals to alleviate global warming by manipulating parts of the Earth’s climate system with geoengineering. Some researchers have suggested that brightening marine clouds by intentionally distributing aerosols could be one way to temporarily mask some of the warming caused by greenhouse gases.

“There are two studies that have looked at different regions of the globe to identify where would be most effective for brightening the clouds,” Fasullo said. “And it so happens that they identify the same region in the southeastern subtropical Pacific that we looked at, and that La Niña ensues if you do that. These are studies from 13 years ago on marine cloud brightening, and that they are relevant to the 2019, 2020 Australian wildfires is just uncanny.”

Yeager said the new study confirms that geoengineering would lead to “knock-on effects that matter for the entire globe in terms of extremes.” And this, he said, “could make you question whether geoengineering is something that’s desirable.”

The new study also showed how the aerosols in the wildfire smoke affected another important piece of the climate system, the Intertropical Convergence Zone, where winds from the Northern and Southern Hemisphere meet and generate almost constant convection. The zone is often visible in satellite images as a nearly unbroken line of clouds extending across the oceans. It’s important because its position determines where rain falls and which areas are dry.

“Its position is dictated by the global energy balance of the Earth,” said Yeager. “When you have an imbalance between north and southern hemispheres, that’s what gives you this shift. And the paper invokes the idea that wildfire emissions cool the southern hemisphere, which shifts the ITCZ north.”

In the broader context of climate change, he added, there are multiple things that are starting to change that hemispheric energy balance, including amplified heating over land, as well as the weakening of key ocean currents that distribute heat energy north and south.

“So you have this tug of war, and then you’re suggesting that, maybe in the future, there’s going to be some kind of systematic change in wildfire emissions that could play a role,” he said. “And we don’t currently evaluate that with climate models, because we don’t have interactive wildfire emissions in our models.”

The current projections for future climate change are based on certain trajectories for greenhouse gases, but they “basically don’t do anything about wildfire biomass emissions into the future,” he said. “They just kind of assume business as usual.”

But climate models that include wildfire emissions as part of the coupled system “is really where we need to be going to answer questions like, are these things going to increase in the future?” he said. “This paper is a great example of new work that’s coming out to attribute certain aspects of climate change that have maybe been off the radar up to now.”

Bob Berwyn an Austria-based reporter for Inside Climate News who has covered climate science and international climate policy for more than a decade.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Dane Wigington at geoengineeringwatch.org has a free video called “The Dimming,” available on the site and is absolutely SHOCKING how we’ve been and continue to be deceived! As the youth chant “There is no planet B.” We can work together for a globally beneficial experience for all, not a few. http://www.peace2030.earth ☮️🙏🏿💕