A Zoo Association Devoted to Science, and Plagued by Scandal

In May 2022, the Henry Vilas Zoo in Madison, Wisconsin, announced that one of its orangutans was pregnant. The announcement of an imminent baby delighted visitors and attracted press. “Bornean orangutans are one of the most endangered species in the world,” zoo director Ronda Schwetz told the local NBC outlet in an interview marking the occasion. “Our orangutans are important ambassadors who connect our community to these animals in the wild and bring a face to the threats they encounter.”

It was a scene that fit the public perception of zoos as sanctuaries of endangered animals. That image is bolstered by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, or AZA, which represents more than 235 facilities in the U.S. and abroad, including the Henry Vilas Zoo, and isn’t shy about emphasizing the major role zoos play in conservation. The organization spends an average of $160 million annually on conservation projects in more than 100 countries, and AZA members — including keepers, scientists, and zoo directors like Schwetz — partner on captive breeding programs for animals from frogs to apes. The collections of animals are also important for research on behavior, diet, and genetics, which further conservationists’ understanding of threatened species.

But behind the admiring coverage, zoo workers across the country, including at the Henry Vilas Zoo, have complained of unsafe working conditions, such as discrimination, sexual harassment, and retaliation. Even as she celebrated the imminent arrival of the baby orangutan in 2022, Schwetz herself faced long-running complaints of creating just such an environment at the Vilas Zoo. And according to allegations in a 2021 lawsuit against Schwetz and the AZA, a culture of secrecy and reprisal reaches into the upper echelons of the organization.

In 2018, court documents allege, Schwetz sexually assaulted a prominent orangutan researcher twice in a hotel room at an AZA conference. (Following generally accepted journalism guidelines, Undark is not including the researcher’s name, as he has not publicly identified himself.) When that researcher informed the AZA nearly a year later, the organization — which has a “zero tolerance” harassment policy — did nothing, despite ongoing complaints of inappropriate behavior.

According to a letter drafted by the AZA to its membership — part of a December 2022 settlement agreement — the organization admitted that it had failed to follow its own harassment guidelines in neglecting to investigate the researcher’s complaint, and that it had similarly failed to step in when Schwetz and other prominent people in orangutan conservation directed a campaign of sabotage and retaliation against him.

The settlement included $2.8 million for the researcher.

In an email response to a request for comment, Schwetz said that the accusations have been hurtful and stressful, but that she firmly denied any wrongdoing. “In consultation with my legal advisors and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums I have agreed to settle this case so that my family and I can move forward with our lives,” she wrote. “It is time for me to focus my full attention now to the important work of wildlife conservation and education in our community.”

In a statement provided to Undark, the AZA also said it was grateful to have reached a settlement. “We have acknowledged and apologized for our mistakes,” the unsigned statement added. “Our focus is forward, continuing in service to our members and advancing the gold standard for modern zoological facilities.”

But in the AZA’s letter to membership following the settlement, the organization was compelled to lay out its missteps, including its failure to take seriously the complaints of a male scientist alleging sexual harassment by a female superior. “We took no action at all. We did not contact or interview the AZA member or attempt any other investigation,” the organization admitted. Instead, the letter goes on to say, AZA leadership told the researcher — a foreign citizen working in the U.S. on a visa — to simply avoid putting himself “in a position where you are alone” with the alleged assailant.

“We are deeply sorry,” the AZA letter stated, “for putting the onus on the victim of sexual misconduct to protect himself from sexual misconduct.”

Both Schwetz and the AZA declined to answer specific questions about the case, and of the many zookeepers and staff Undark contacted, only a few agreed to speak on the record; the rest declined or spoke on the condition that they not be identified, for fear of professional reprisal. But background interviews, court documents, text messages, and emails uncovered as part of the lawsuit and obtained by Undark offer an unusually public glimpse into the secretive world of American zoos. They also depict the AZA as an organization where structural dysfunction reaches well beyond a single case of alleged harassment, and where unchecked impunity seems to protect people at the top while driving others out.

Among other things, critics say, this is hampering the important scientific and conservation work that the AZA itself claims to champion.

The AZA’s influence on American zoos is vast. The organization took its modern shape as an accrediting body in 1972, aiming to improve zoo conditions by setting standards.

As more zoos joined, the organization grew into something between a cooperative network and a quasi-regulatory body. AZA boards and committees run conservation programs and industry meetings, and firmly control accreditation — the loss of which can have direct repercussions, including moving animals to other institutions. Some facilities have AZA accreditation as a requirement in their charter or lease. That gives the AZA a lot of power, Grey Stafford, a zoo consultant, and AZA member since 1990, told Undark.

The AZA also wields power through steering committees of the Species Survival Plans, or SSPs, formal groups that manage breeding, genetic diversity, and distribution of species through member zoos. Such committees can control which zoos receive and breed animals. They can also help — or hinder — an outside researcher’s ability to work at member zoos.

While SSP decisions are often impartial, the reasoning behind them can be opaque, sources told Undark, and sometimes reward or punish according to personal whims. Often, these professional opportunities act as levers of power. “Who gets to have an orangutan baby at their zoo this year?” said Barbara Shaw, who serves as a board member of the Orangutan Conservancy. “Which zoos get to host the next conference?” and “Which keepers get to go to Borneo?”

And while SSPs are notionally democratic — the steering committee is elected by zoo representatives — participation is uncompensated. This can present a problem for many keepers who want to participate, but who are already poorly paid: One study found that average pay at AZA zoos doesn’t meet the amount needed for a living wage for a single parent. Most SSPs are filled with people in upper management positions; some, several sources told Undark, effectively become the personal fiefdoms of a few long-standing members.

“Researchers are sort of at the mercy of the SSP, wanting that endorsement,” the former director of an AZA-accredited zoo told Undark (the director did not want to be named publicly out of concerns of reprisal). While some great research has come out of SSPs, the director continued, with the system’s current set-up, “it could be easy for an SSP chair to let their own personal beliefs, or their own personal opinions, come to the forefront before it ever reaches the rest of the committee.”

Dedicated research positions aren’t common in zoos, so staff members have to figure out how to do science on their own time, if at all. “It’s a very deprioritized part of your labor,” a zookeeper at an AZA-accredited zoo told Undark. (The zookeeper did not want to be named publicly out of concerns of professional reprisal.) When mistreatment or abuse becomes a pervasive part of the working environment — as the zookeeper said they had seen to varying degrees at every institution they’ve worked at — “that research goes out the window first.”

This mixture of interpersonal tension and systemic discontent can undercut important work at zoological institutions — including data collection, working with field scientists or zoo colleagues, or animal welfare projects. “If we collected data on the span of project graveyards in zoos,” the zookeeper added, “it would be shocking, the amount of resources that get lost on projects that get scuttled for harassment reasons and for general turnover from really poor compensation and staff welfare.”

But if turnover in the ranks is common, critics argue, management has a way of sticking around. “There’s just these specific people who hold so much power,” said Kimberly Terrell, former director of research and conservation of the Memphis Zoo, who says her institution settled with her over gender discrimination and retaliation in 2018. “And if you cross one of them, then forget it.”

Ronda Schwetz has a long history working with primates. She began her professional career at Disney’s Animal Kingdom theme park before moving on to the Denver Zoo. (Both institutions are AZA members.) She was also part of a close-knit group of friends who held key roles in the Orangutan SSP. Schwetz herself served as field committee chair under her friend Lori Perkins, the decades-long coordinator of the orangutan SSP.

In 2010, Schwetz met a promising young researcher studying orangutan genetics in southeast Asia. According to the researcher’s declaration, which was part of the 2021 complaint, Schwetz offered mentorship, professional connections, and sample storage at the Vilas Zoo. A few years later, the researcher moved to the United States on a work visa sponsored by Schwetz and worked as an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 2017, the researcher’s office and lab — including thousands of DNA samples, representing a decade’s worth of work — were at the Vilas Zoo.

By some public accounts, the zoo was not a happy working environment. In an interview obtained by the Wisconsin State Journal in 2022, amid complaints of racial discrimination and harassment, one of the zoo’s only two Black zookeepers said management was “more interested in their personal vendettas against certain staff members” than animal welfare. The other compared it to a “North Korean dictatorship” where “dissent is not tolerated.”

According to court documents and public accounts, Schwetz allegedly had a reputation for inappropriate behavior both at Vilas Zoo and in the broader zoo community. In 2019, employees of the Henry Vilas Zoological Society, a nonprofit that manages concessions and other guest services, accused Schwetz of making sexually explicit and demeaning comments to staff. At conferences and work meetings, multiple sources alleged that Schwetz was known to drink heavily and get physical. “She would go around the room kissing us,” a former curator wrote in an August 2021 affidavit filed as part of the orangutan researcher’s lawsuit. Schwetz, the curator wrote, also openly discussed sexual encounters at AZA conferences in “explicit detail.”

In 2018, the researcher who filed the 2021 lawsuit was invited to speak at the AZA annual convention in Seattle. Attendance can be expensive, especially given low zoo wages. While the Vilas Zoo would fund the researcher’s travel and registration, Schwetz told him, he’d have to share her hotel room. It wasn’t unusual; sources told Undark that it was common for zoo staff to bunk together during conferences to defray costs.

Court documents — including a 2020 police report, corroborated by an email received at the time by Shaw, the Orangutan Conservancy board member — allege that on the first night of the conference, Schwetz returned to the room drunk and despondent. She grew verbally abusive and sexually aggressive, the documents allege, assaulting the researcher and groping his genitals. The next night — after climbing into the lap of an unnamed man at the hotel bar and unbuttoning his shirt, which earned her a verbal complaint from a nearby AZA official — a visibly intoxicated Schwetz again returned to the room and allegedly assaulted the researcher, climbing naked on top of him in the middle of the night.

In a 2022 deposition, Schwetz denied each of the researcher’s allegations. “I believe he hugged or patted me on the back to console me at one point,” she said. “I recall something along those lines.” Schwetz did not respond to a detailed list of questions from Undark regarding these specific allegations.

The morning after the alleged assault, according to the researcher’s declaration, Schwetz took him to breakfast and asked if she’d come on to him the previous night. When the researcher responded that he didn’t want to talk about it, Schwetz allegedly told him loyalty was important to her, and “she knew I would always have her back.”

The implicit threat was clear, the researcher testified in a victim impact statement: “She could take away my job, my income, my home, my relationships — my entire existence — by virtue that she controlled my immigrant work visa to the United States.” In her testimony, Schwetz disputes this, saying she wasn’t the researcher’s day-to-day supervisor and that he was “at all times employed by” the university.

He testified that after the incident, he planned to keep his head down and search for a new job. He said he previously had friendly relationships with many on the steering committee: They’d endorsed his projects and provided access to research samples. He had even visited Perkins and her wife a few months before the Seattle conference.

Yet even as he sought to separate himself from Schwetz, text messages obtained by attorneys as part of the lawsuit suggest that members of the Orangutan SSP abruptly cooled on him, calling him a “baby” and “a petty piece of shit.” The researcher’s requests for genetic samples from the Denver Zoo, which had previously gone through without problems, also stalled. In March of 2019, while the researcher was applying for a job at the St. Louis Zoo, Perkins reached out to a friend at the institution who’d had conflict with him to make sure he’d provide “good diligence” in the hiring committee.

In her deposition, Perkins denied active retaliation, but admitted that Schwetz had spoken to her about the situation, and that despite her formerly close relationship with the researcher, “I was not being a good friend to him.” Perkins did not respond to a request for comment from Undark.

By the fall of 2019, the researcher — now with a green card — had retrieved his samples from the Vilas Zoo and moved into a new offsite lab at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center. He had also lined up a promising new job as a conservation scientist at Brookfield Zoo in the Chicago area. No longer under Schwetz’s direct control — and concerned about a confrontation at an upcoming Orangutan SSP meeting — he says he decided to report the assault.

At the time, however, the AZA had no third-party human resources for handling such complaints. The researcher might have made a report to the ethics board, but ethics charges are not anonymous, requiring a signature from the complainant — and in 2019, Schwetz herself was on the board.

The researcher instead decided to file his assault report to Kris Vehrs, then the executive director of the AZA. It was, theoretically, a report that the AZA should have responded to promptly. “I have heard many personal stories about sexual harassment during past AZA conferences,” wrote AZA’s chief executive Dan Ashe in a March 2018 email to members, highlighting the organization’s new “zero-tolerance” harassment policy, which he noted applied in all conference-related venues, including hotels. The organization’s board of directors reiterated that position in an email two months later.

Vehrs was also aware of some of Schwetz’s past behavior. After the 2018 meeting in Seattle, court documents say, Vehrs had reprimanded Schwetz for her actions at the hotel bar. “Schwetz admitted this conduct and admitted she was intoxicated,” the AZA’s legal team noted, after which Vehrs “verbally sanctioned Schwetz,” warning her that future offenses at AZA conferences would get her banned. And in February 2019, AZA staff received an anonymous complaint alleging Schwetz had become inebriated and inappropriately touched a person during a meeting in Nashville.

Yet in an emailed response to the orangutan researcher’s assault report, Vehrs claimed the AZA had already addressed Schwetz’s behavior and didn’t expect her to repeat it. If the researcher was uncomfortable with Schwetz, Vehrs wrote: “My recommendation to you is do not put yourself in a position where you are alone with her.” Vehrs did not respond to a request for comment from Undark.

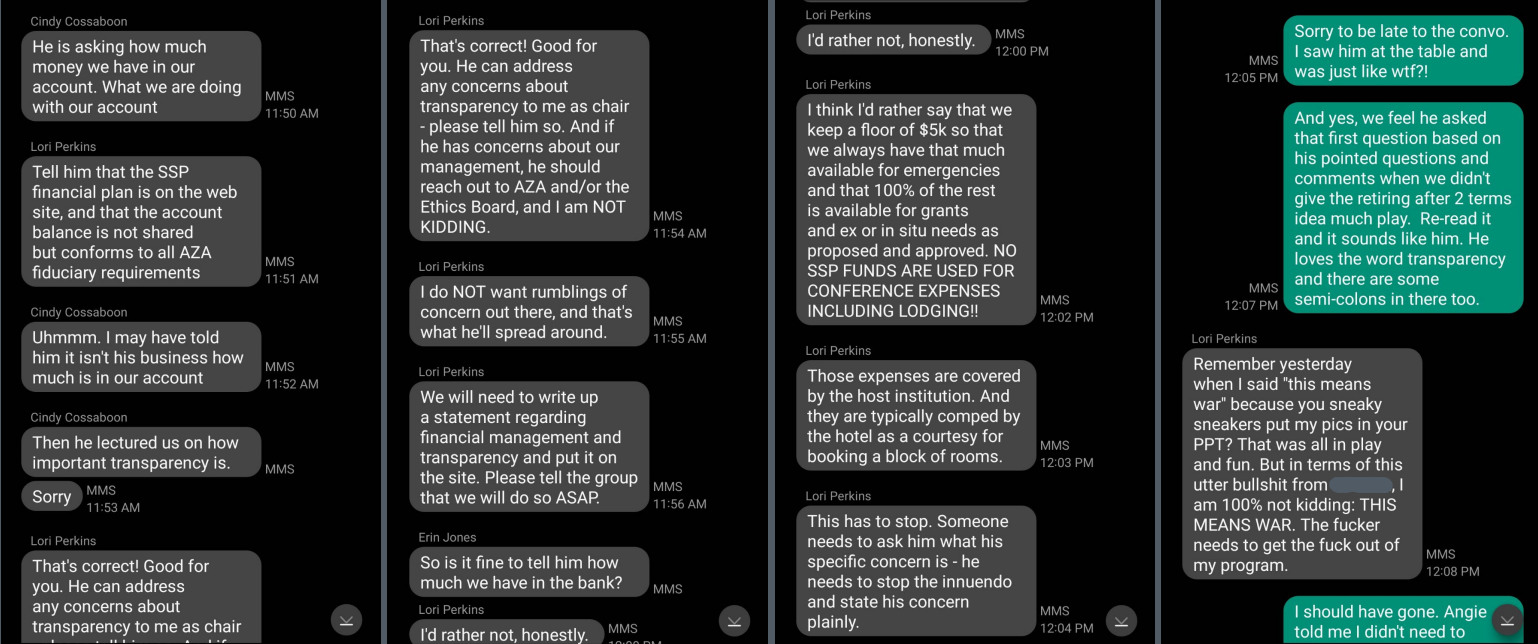

Text messages from August 2019 amongst members of the Orangutan SSP steering committee were hostile regarding the researcher’s presence at a group meeting. (“Too bad I didn’t take the workshop chair position,” Denver Zoo’s Cindy Cossaboon texted. “I’d have kicked his ass out.”)

At the meeting, various attendees, including the orangutan researcher, raised concerns about the SSP’s lack of transparency about how it was using funds.

While court documents don’t seem to indicate any actual financial malfeasance, the questions hit a nerve. “I may have told him it isn’t his business how much is in our account,” Cossaboon texted the steering committee, warning that the researcher’s “new strategy is to take over the SSP and kick us out.” An increasingly angry Perkins, the SSP coordinator, wrote: “In terms of this utter bullshit, I am 100% not kidding: THIS MEANS WAR.”

Referring specifically to the orangutan researcher, Perkins added: “This fucker needs to get the fuck out of my program.”

Soon after, the researcher’s work opportunities shrank again. According to a deposition of Lance Miller — the researcher’s new boss at the Brookfield Zoo and a former colleague of Schwetz’s — Perkins and Schwetz approached him citing serious — but vague — concerns about the researcher. Not long afterward, the Brookfield Zoo fired him.

In response to a request for comment sent to Miller, Sondra Katzen, director of public relations for the Chicago Zoological Society and the Brookfield Zoo, told Undark the zoo was unable to comment, stating “they were not a party to the lawsuit, have not been accused in the lawsuit.”

The termination interfered with the researcher’s work on orangutan genetics, which were tackling an important question in the animals’ management. Since the 2017 discovery of a new species of orangutan, zoo officials had been trying to work out whether any of their animals belonged to the newly described group — and whether they’d accidentally interbred it with other captive orangutans. As a longstanding scientific partner with AZA orangutan conservation committees and someone who’d been collecting genetic samples of the apes for over a decade, the researcher was initially an active voice in these projects.

After August 2019, however, the SSP reached out instead to other scientists. By November, emails suggest, a key AZA orangutan program — with which the researcher had previously been listed as an advisor — had also quietly dropped him.

“A lot of times the research that’s done in the zoo world is focused on very practical things — nutrition and reproduction and things that are important to maintaining healthy captive populations of animals,” Terrell said. As a result, interpersonal conflict — anything from bruised egos, territoriality, unethical research practices, or harassment — “can end up delaying the publication and dissemination of research.”

The researcher reported the alleged sexual assault to the police in 2020, resulting in a criminal complaint against Schwetz that ended with a deferred prosecution agreement in October 2021. Suspecting retaliation, he also filed a civil suit against the AZA and Schwetz in King County Superior Court in June 2021, centering on the AZA’s handling of his sexual assault report and the subsequent professional setbacks.

As part of the deferred prosecution, Schwetz had signed a no-contact provision, forbidding her from directly or indirectly interfering with the researcher. Yet over the course of the civil suit, Schwetz texted with steering committee members Cindy Cossaboon and Megan Elder, writing that the researcher was “coming off as crazy” as he testified to dealing with suicidal ideation and partial hospitalization.

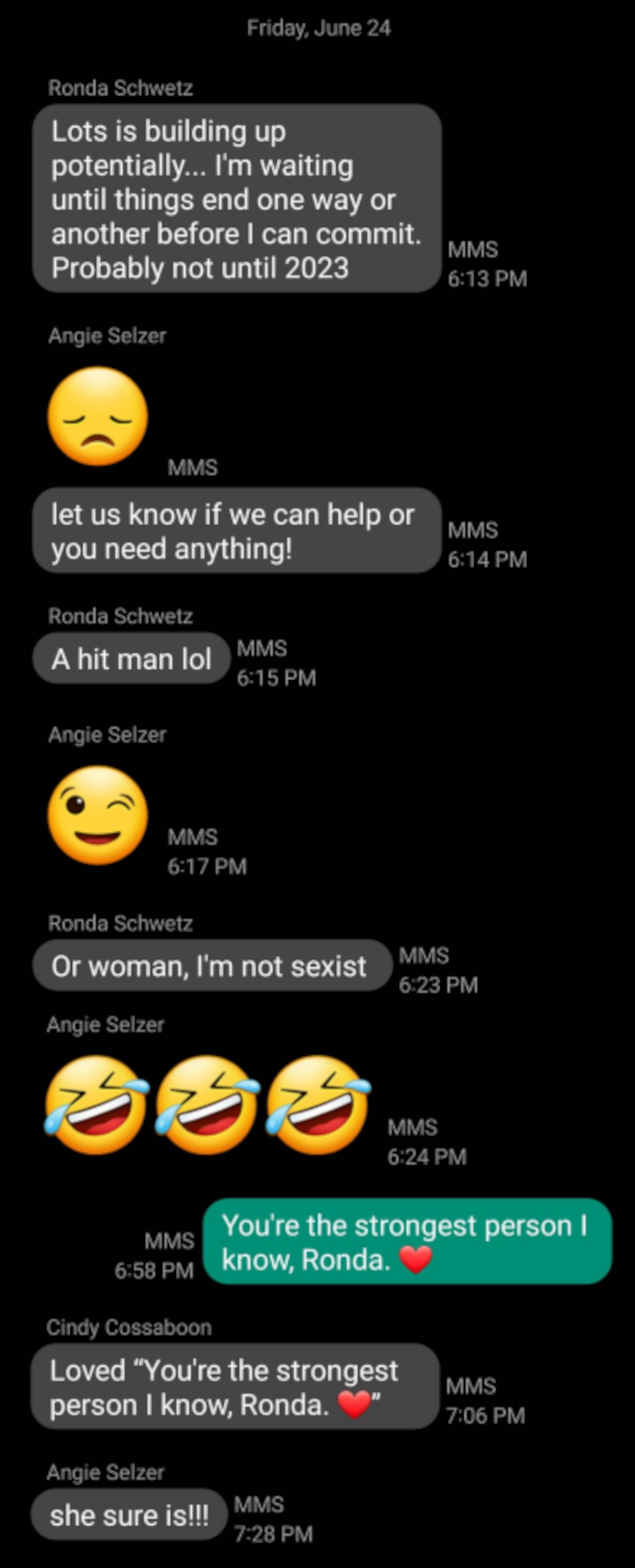

In a June 24, 2022 group text, an SSP member asked Schwetz if she needed anything. Schwetz responded: “A hit man lol” later adding “or woman, I’m not sexist.”

“You’re the strongest person I know, Ronda <3,” Elder replied.

Text messages between Schwetz and members of the SSP in June 2022.

Visual: Undark

Court documents suggest that the AZA tried to get the researcher’s lawsuit dismissed, arguing that they weren’t an “enforcement agency” and weren’t responsible for what occurred at conferences, so long as it didn’t occur at a programmed panel: “Simply, whether AZA members engage in sexual activity on their own in private homes or rooms and on their own time is not relevant to this suit.”

Under deposition, however, CEO Ashe and Vehrs said that the AZA had knowledge of Schwetz’s previous inappropriate behavior at conferences, and had mishandled the complaint. “I wish I would have conducted an investigation,” Vehrs told lawyers. “That would have been the right thing to do.”

In the December 2022 settlement, in addition to requiring Dane County and the AZA’s insurers to pay a combined $2.8 million, the terms mandated that the AZA offer a third-party reporting and investigation system — one that could not include current or former members. Perkins, Cossaboon, and Elder were recused from any matters related to the researcher who filed the complaint.

As part of the settlement the AZA also had to issue a public statement to AZA members. “Once we learned of the attack and retaliatory conduct, we should have worked to prevent retaliation by these individuals,” the statement concedes, before noting that “because we did nothing,” they had failed their membership.

Schwetz, meanwhile, agreed to resign from the Orangutan SSP and other key committees and was barred from AZA conferences for three years, as well as from events attended by the researcher for two more. (The AZA, meanwhile, agreed not to “proactively” cancel Schwetz’s membership in the organization.)

Current and former AZA members speaking to Undark expressed anger that AZA had placed itself in this position. The settlement “ought to be raising a lot of hell” among membership, Stafford said.

While the settlement didn’t explicitly acknowledge that the defendants broke the law, Marty McLean, the orangutan researcher’s lawyer, told Undark, their agreement is the closest to an admission of guilt he’s ever seen. The organization’s initial response was appalling, he said, but he’s hopeful that “they’re going to try and make an honest effort to do better moving forward.”

Still, AZA’s commitment remains unclear. Notably, the organization seems to have weakened its code of conduct in 2022, stripping coverage for informal gathering places like hotel bars and removing language obliging it to act on reports. The organization also seemingly deleted Ashe’s 2018 MeToo-era blogpost from its website.

Of the people Undark interviewed, most noted that the case was consistent with the larger culture inside the AZA — a culture which can end up directly undercutting conservation and scientific research. While local zoos are at the forefront of making research connections with outside scientists, these experts said, the insular, tight-knit world of the AZA can mean trouble for anyone who rocks the boat.

“It can limit your research in many different ways,” Terrell said, from getting blocked from working with animals or seeing projects “sabotaged for things related to a toxic workplace.” This particular case, she added, wasn’t just about one or two people’s behavior: “It was a problem of a system that didn’t take those issues seriously.”

Schwetz remains director of the Henry Vilas Zoo. In a letter sent in March to County Board Supervisors, she claimed to still hold a position on the SSP, in apparent violation of the settlement.

The researcher who filed the suit now works from an independent lab on a federal grant, and is no longer directly affiliated with an American zoo.

Asher Elbein is a writer based in Austin, Texas. His work has appeared in The Oxford American, the Texas Observer, and The Bitter Southerner.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

The hypocrisy of AZA’s “accreditations” undermines the important work of its members. Specifically the zookeepers.

Why is it ok for some zoos to not have a vet on staff, or even a vet tech and others have full healthcare teams?

AZA has guidelines so broad it leaves too much open to individual interpretation.

I guess as long as stuff looks good on paper?

Schwetz should be terminated like any CEO involved in this type of scandal would be. They’re protecting her.

Why is this Schwetz person still employed by the zoo at all? Is this the conduct that is allowed at the zoo? Is the zoo privately owned or city?

You have barely scratched the surface of the hypocrisy of AZA. I hope you continue to dig.

Allowing “world famous zoos” to surplus animals to animal dealers in Texas.

150 acre zoos are inspected over 3 days with 3 inspectors. 14 acre zoos are inspected over 3 days with 3 inspectors.

Zoos that have major issues are accredited until something comes out in the news and AZA has egg on their face. Then they lose accreditation for a year before the “good old’ boy club” steps in and pats them on the back. You scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours kind of thing.

Please keep digging!

Asher Elbein’s story revealing the underside of Zoo management and research is a great job of journalistic investigation. He leaves no stone unturned..great job!