Johan Eklöf was a graduate student in 2001 when he found himself deep inside Malaysia’s Krau Wildlife Reserve. He was there to attend a workshop on bats, his favored creatures of the night, and a television crew was on site. “One evening, during dinner, one of the film crew’s large lights was left on, directed up toward the sky,” Eklöf recalls early on in “The Darkness Manifesto: On Light Pollution, Night Ecology, and the Ancient Rhythms that Sustain Life.”

BOOK REVIEW — “The Darkness Manifesto: On Light Pollution, Night Ecology, and the Ancient Rhythms that Sustain Life,” by Johan Eklöf (Simon & Schuster, 272 pages).

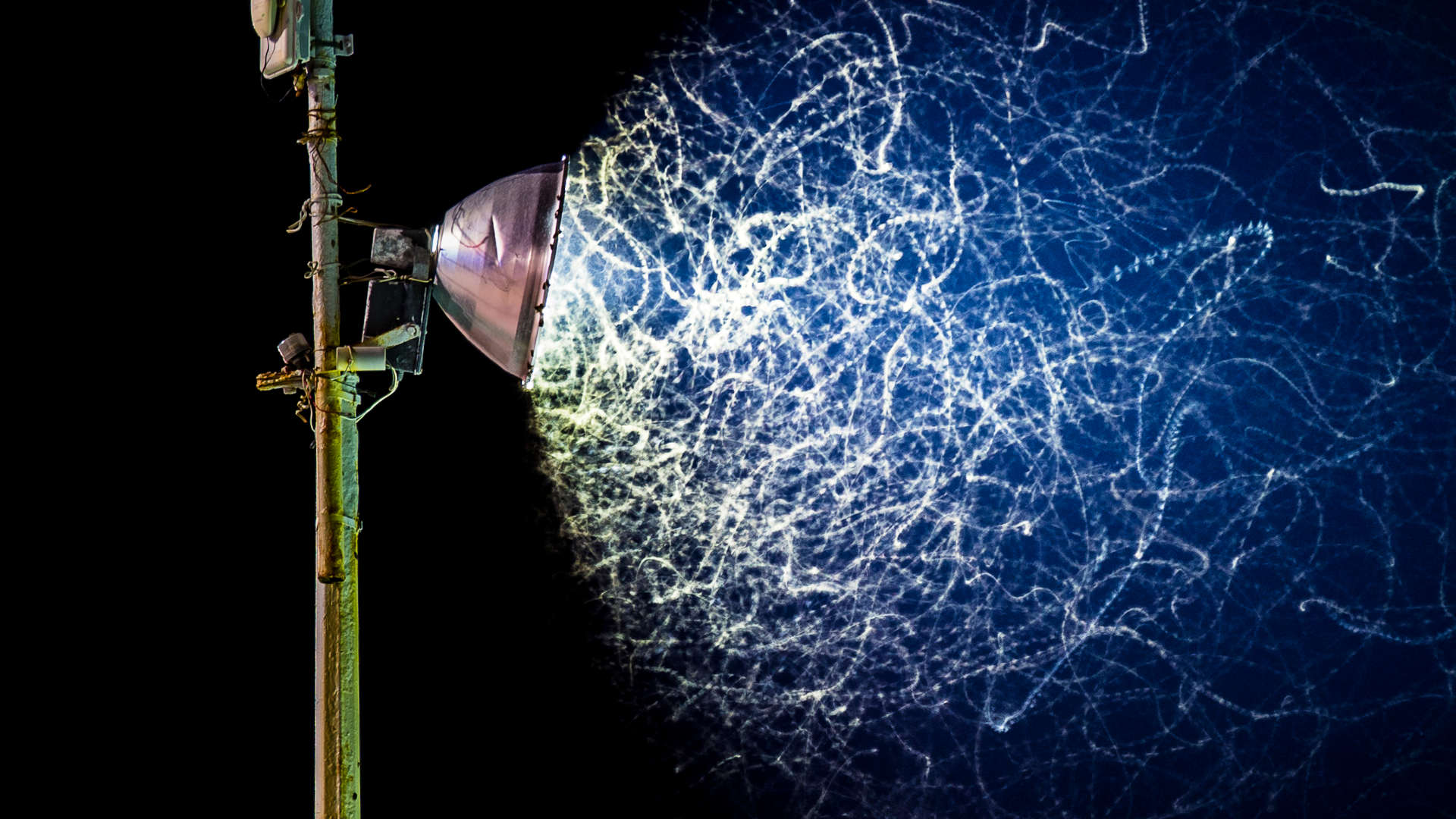

Lured into the tight column of illumination, a “heavy stream” of the forest’s winged inhabitants “danced in a spiral down toward the light,” he writes: moths, caddis flies, mosquitoes, beetles, crickets, and more. Eklöf sat for a long time watching that dance — and was transfixed by a praying mantis that came to prey on the bugs.

“In insect circles,” according to Eklöf, it’s known as the “vacuum cleaner effect,” and it’s just one of the many ways that artificial light has a profound effect on the natural world. The nocturnal illumination that sustains our modern existence seems to disrupt the lives, and circadian rhythms, not just of insects but of animals as varied as bats, birds, plants, turtles, coral, and clownfish.

Eklöf, a bat researcher and self-proclaimed “friend of the darkness,” is concerned about the cascading ecological effects of what he and other experts call light pollution. In 42 short and digestible chapters, he makes the case that light pollution is a crucial feature of the Anthropocene Epoch: the period of time in which human activity has impacted the planet’s dynamics.

Although scientists debate when the Anthropocene began, the seeds of light pollution were sowed more than 150 years ago. By the mid-20th century, as electricity and artificial lighting spread across much of the Earth, “the future was bright,” writes Eklöf, “or, at least, brightness was the future.”

Artificial light, according to Eklöf, accounts for 10 percent of our energy use, but just a fraction of that is actually useful. “Badly directed and unnecessarily strong lights cause pollution that is the equivalent to the carbon dioxide emissions of nearly 20 million cars,” he writes.

Scientific research into how, and how much, light pollution has affected the daytime-nighttime rhythm of life on Earth is still relatively sparse. In lyrical but straightforward prose, “The Darkness Manifesto” nevertheless details some worrying and compelling, if preliminary, findings.

Take the population of land-dwelling insects, which is currently dropping, on average, by about 1 percent per year. Insects account for the vast majority of the species on the planet, and play a crucial role in pollinating plants, helping with the decomposition of dead things, keeping weeds and other plant pests in check, and providing nutrition for animals above them in the food chain.

“The reasons for insect death are many, from urbanization and global warming to the use of insecticides, large-scale farming, single-crop cultivation, and disappearing forests,” writes Eklöf. “But for anyone who’s ever seen an insect react to light, it is obvious that light pollution is a major cause.”

Around half of insects are nocturnal and use the dark hours to feed and find reproductive partners. “The night’s limited light protects these insects, and the pale glow from stars and the moon is central for their navigation and hormonal systems,” Eklöf writes.

Moths travel straight by keeping track of the Moon. Other bugs won’t fly at all when there’s light, lest they become easy prey, so artificially illuminated evenings keep them grounded. Crickets whose world is too lit don’t sing and can miss their mating ritual. “Disturbances in the natural oscillation between light and dark is therefore a threat to the night insects’ very existence,” Eklöf concludes.

Artificial lighting also takes a toll on birds, which sometimes die en masse when they fly into lit towers or lighthouses. But birds also, Eklöf details, rely on the amount of light to know when to reproduce, and artificial light can upset that balance and make them ready to mate at the wrong time.

As for bats, they hunt nocturnal insects, of course, while using the cover of darkness to hide themselves from predators. They live in caves, under bridges — and particularly in Eklöf’s home country — in church towers. In the 1980s, he writes, two-thirds of churches in southwest Sweden had their own personal bat colonies. But Eklöf’s own research suggests that number has dropped by a third. “The churches all glow like carnivals in the night,” he writes. “All the while the animals — who have for centuries found safety in the darkness of the church towers and who have for 70 million years made the night their abode — are slowly but surely vanishing from these places.”

In the final section, Eklöf speaks to the impact of light pollution on our bodies and imagination. For one thing, the northern lights are obscured. So are stars. “They are there,” he says, “but not there for us to see.”

In North America, almost 80 percent of the population can’t see the Milky Way, research shows, along with 60 percent of Europeans. “People in Hong Kong sleep under a night sky that is twelve hundred times brighter than an unilluminated sky,” Eklöf writes, “and if you were raised in Singapore, you’ve likely never experienced night vision.”

What’s more, artificial light disrupts our bodies’ production of melatonin, the hormone that helps control the sleep cycle, with profound effects on our natural sleeping rhythm, writes Eklöf. “We may not be able to cure or prevent depression all at once by cutting down on electric lighting,” he maintains, “but we definitely increase the chances of good sleep in the long run.”

In lines of thought like this, Eklöf nods to the lack of hard science proving the links between synthetic light and the problems he details. And regardless of how much artificial light contributes to health, insect decline, and ecosystem disruption, he notes that other factors like climate change also play a key role. “It will be extremely difficult, if not yet impossible, to stop the runaway temperatures on earth, to clean up our environment of plastics and poisons, and to prevent the spread of invasive species — plants or animals in the wrong places,” he writes. “It’s markedly easier to dim or turn off the lights.”

And though the book contains more gloom than guidance, he offers some practical advice to help the cause: Turn out the lights when leaving a room, for example, put motion detectors on the porch lights, and direct streetlights downward and make their light less blue.

In the end, though, Eklöf understands that it’s simply in our nature to want to illuminate the world: “The darkness is not the world of humans. We’re only visitors.”

Even so, he urges readers time and again to embrace and appreciate nighttime for what it is. Or, as he puts it: “Carpe noctem.”

Sarah Scoles is a freelance science journalist based in Denver, a contributing writer at Wired, and a contributing editor at Popular Science.