A Rare Disease That Underscores the Importance of Abortion Access

It took a long time and numerous instances of nearly fainting for Renee Schmidt to figure out what was going on. Her symptoms became really noticeable as she headed to college at age 18, she recalled. About once a month, when she turned her head, she would feel herself start losing consciousness or experiencing momentary memory loss. On a few occasions, she fully passed out. Over time, the episodes occurred more frequently, sometimes 20 to 40 times per day. Schmidt had to drop out. “I couldn’t do school anymore. I was pretty much in bed all day for six months at least,” she said, “which was not ideal.”

Three years after her symptoms emerged, Schmidt was diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. EDS is a cluster of often rare, poorly understood, inherited diseases that impact connective tissues. The disorders are caused by defects in collagen, the most abundant protein in the human body, providing structural support to ligaments, tendons, and many organs. EDS symptoms can include chronic fatigue, pain, dislocations, and even surprising conditions like aortic aneurysms. In Schmidt’s case, EDS was responsible for her spine’s laxity, which allowed her vertebrae to compress her brainstem when she turned her head.

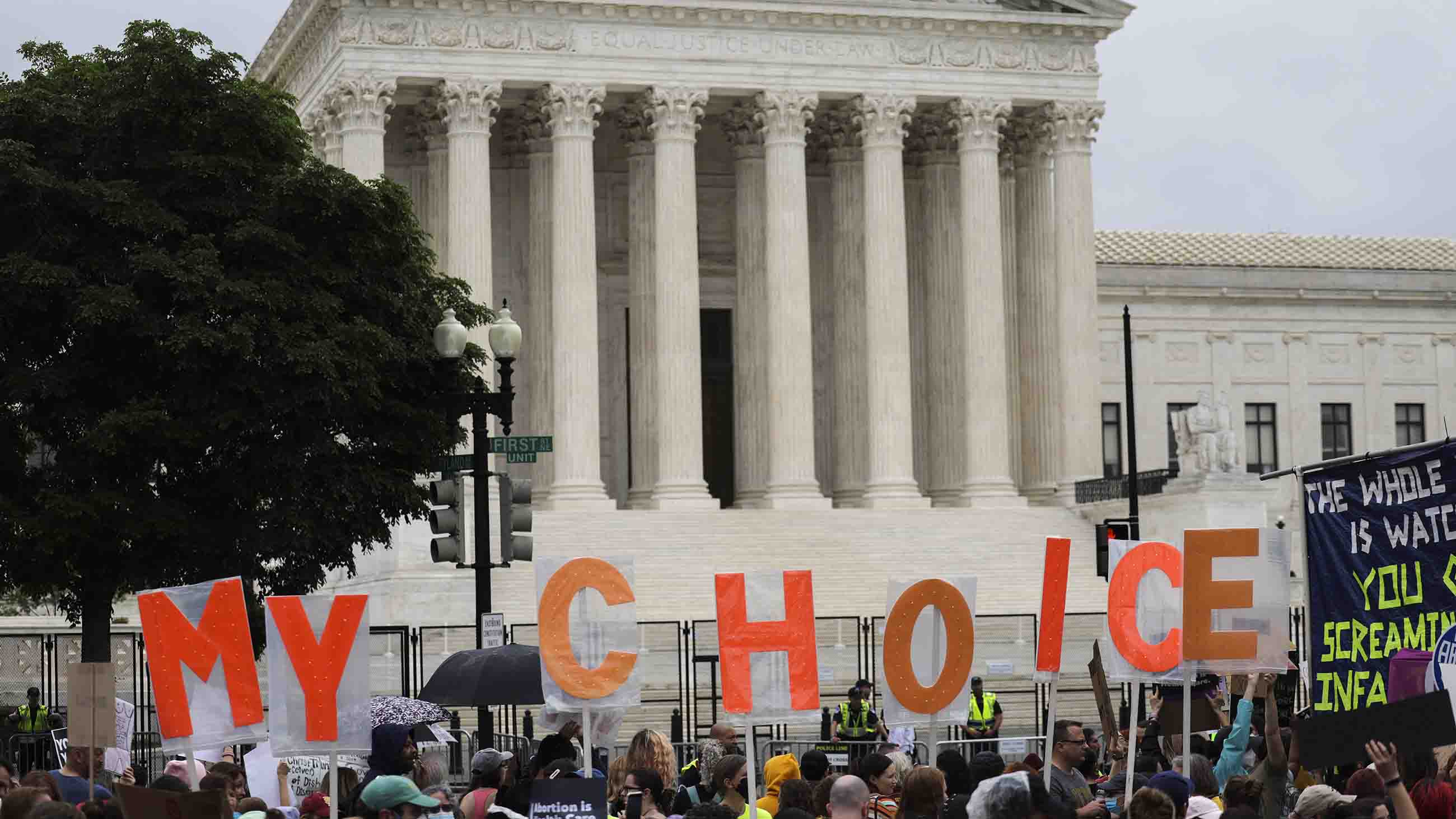

This past June, the Supreme Court of the United States reversed the nearly 50-year-old abortion rights case known as Roe v Wade, allowing individual states to once again ban or limit access to abortion. It was a move that critics argue will likely compromise the health of people who may become pregnant — particularly those with conditions like EDS. Like many other illnesses, EDS can complicate pregnancy, and a lack of access to abortion can put people with the disorder at risk of particularly difficult pregnancies, medical experts and patients told Undark. For EDS, pregnancy complications can include death in rare cases.

This matter is further exacerbated by a lack of awareness of the disease among medical staff, including those involved in maternity and birth. To address this, researchers in the field have teamed up with the nonprofit Ehlers-Danlos Society to explore these complications, and establish care guidelines.

Around the world, an estimated one in every 5,000 people, or 0.02 percent of the population, has a form the disease. (By contrast, active epilepsy, which can also complicate pregnancy, affects an estimated 0.6 percent of the population. And gestational diabetes affects an estimated 4 percent of pregnant women.) Some think EDS cases might be undercounted. The condition is so unknown and misunderstood among medical staff that patients can go 10 and 20 years without a diagnosis. “Within every single type of EDS — even the ultra-rare — it is being missed or underdiagnosed,” said Lara Bloom, president and CEO of the Ehlers-Danlos Society.

Regardless of numbers, the team behind the Ehlers-Danlos Society project hopes that the work will make pregnancies and births safer for patients, including those in states that have banned abortion. The condition can make pregnancy more painful, uncomfortable, and potentially risky, said Sally Pezaro, an adjunct associate professor at the University of Notre Dame Australia and an assistant professor at Coventry University. Pezaro researches and practices midwifery, and is leading the EDS Society project. Because of the possible complications associated with pregnancy, she said, patients may wish to terminate — though women in states with abortion bans may not get to make this call. Still, she said she hopes that her work will make pregnancy and delivery smoother and less dangerous:

“It will hopefully increase your physician’s knowledge about things to reduce the risk, or manage the risk appropriately.”

Understanding EDS’ impact on pregnancy and birth is complicated by the fact that there are 14 known types of the disease and an array of symptoms. Patients with the most common variety, hypermobile EDS, or hEDS, often have joint hypermobility and experience dizziness and gastrointestinal problems, among other things. Patients with the second most common type, classic EDS, often have loose skin and experience poor wound healing. One of the rarer and more dangerous types is vascular EDS, or VEDS, which comes with an increased risk for rupturing of the intestines, uterus, and various blood vessels.

According to Pezaro, EDS can complicate pregnancies in a few ways, though pregnancies with hEDS are not usually life-threatening. During pregnancy, changes in hormone levels cause joints to relax. With already weakened connective tissue, all patients with EDS can face a number of issues. For instance, they can have contractions that last for weeks, and then deliver rapidly and unexpectedly. As such, Pezaro said, they may not be near medical help when their baby comes.

Lacerations to the vaginal wall during labor and Caesarean sections may heal more slowly than is typical. EDS also increases the risk of vaginal or rectal prolapse and hemorrhage. A survey of more than 1,700 people found that those with the disorder reported higher rates of miscarriages, stillbirths, and terminations, compared to those without it. The results were published earlier this year.

Vascular EDS is associated with uterine ruptures, aortic dissections (tears in the largest artery in the body located in the heart), and even death. According to one paper from this year, the maternal mortality rates for people with VEDS can vary from 4 to 25 percent, compared to the U.S. average of 0.024 percent (23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

According to Laura McGillis, a nurse practitioner at the GoodHope Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome program in Toronto who is part of Pezaro’s team, drafting the guidelines involves determining and using the best available research. But, she said, “We don’t have all the answers because there’s not a lot of literature that’s posted on this.”

Nevertheless, since the effort began early this year, the researchers have already identified key information to be included in the guidelines, including details about the need for a multidisciplinary care team. Health care providers will also be advised to prepare for fast births, and, when necessary, to use non-dissolvable stitches because people with EDS may fail to heal before dissolvable stitches disintegrate, leaving the patient open to infection. The researchers hope to finalize the guidelines by the end of this year and then get them published.

Knowledge among medical staff is quite rare, said Bloom, and EDS patients often find it hard to locate an informed practitioner. “I think, in medical school, most people are taught about EDS with a small paragraph,” she said. “So that certainly needs to change.”

In an email to Undark, Kate Connors, director of communications and public affairs for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the organization did not have data on how many of its members were aware of EDS and its complications. Similarly, Natalia Kimrey, associate director of marketing and communications for the American College of Nurse-Midwives wrote in an email that her group “would not have data on the relative level of awareness about EDS among midwives in the United States.”

The EDS Society created an international consortium of medical professionals and experts whose names and affiliations can be found on the society’s website. The website also includes a page where knowledgeable health care professionals can add their names to a directory.

People with EDS may face particular challenges in states that have banned abortion. Schmidt — who protested the end of Roe outside the Supreme Court — eventually got surgery for her condition in November of 2020, a month after her EDS diagnosis. (Her joints were hypermobile enough to fulfill the criteria for hEDS, though she hasn’t done genetic testing to rule out other EDS types.) The surgery included the installation of a device linking her skull to a vertebra in her neck in order to keep everything in place. However, Schmidt noted, had she gotten pregnant before the procedure and had she lived in a state that banned abortion, pregnancy, labor, and delivery could have killed her.

Also, people with EDS may require medications that could harm fetuses, such as some blood pressure drugs and occasionally opioids. It may not be possible to wean off these medicines prior to an unexpected pregnancy or find alternatives that are both effective and fetus-safe, Schmidt said.

Other EDS patients share these concerns, said Mandolyn Orrell, director of the Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Support Group of Asheville, North Carolina. The group’s Facebook page has 2,727 followers. Because North Carolina recently banned abortion after 20 weeks and six days, people with EDS may be forced to carry a baby to term, and face the risks that poses. “Truly, they could lose their lives,” she said of people with EDS living in states that ban abortion. “That’s what it boils down to.”

Currently, there are no laws prohibiting people from traveling to other states for abortions. But some states have created so-called bounty hunter laws, allowing any citizen to sue someone who helps another person get an abortion, including a partner who drives them across a state border, said Carrie Baker, a professor in Smith College’s Program for the Study of Women and Gender.

Further, travel can be time-consuming, uncomfortable, and expensive for people with pre-existing conditions, according to Svetlana Blitshteyn, a neurologist at the University at Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences who regularly works with people with EDS. Traveling is also expensive, which could be an issue considering many people with EDS may find it difficult to work due to discomfort or pain. Blitshteyn also noted that any abortion doctors that people with EDS go to in other states aren’t likely to know about their condition or medical history.

Some people with EDS may elect to not have children — a choice that abortion bans may take away. McGillis noted that the chronic pain, joint instability, gastrointestinal issues, and migraines that can come along with EDS may be too much for a person to handle while also raising a family. As a genetic disease, EDS can be passed down to one’s children: hEDS, for instance, has a 50 percent chance of being inherited. Some people may not want their children to inherit the disease. Passing down these disorders “forcibly, to a child — it’s just not ok,” Orrell said.

These concerns resonate beyond the EDS community. Since Roe was overturned, providers of reproductive healthcare have said that the contentious nature of the abortion debate has resulted in suboptimal care, and some have pointed to data indicating that abortion bans are likely to lead to higher rates of maternal mortality.

The loss of Roe “has spurred widespread fear and confusion amongst the public, and creates unnecessary challenges for patients who need abortion care,” said Sarah Diemert, director of medical standards integration and evaluation at Planned Parenthood Federation of America, in an email to Undark.

Diemert added: “For many pregnant people, there are medical reasons why they may want or need to consider abortion in order to avoid serious, potentially life-threatening complications. Given the state of abortion access across the country, pregnant people may be forced to carry pregnancies to term against their will at risk of their health and life. This is unacceptable.”

Many states that have banned abortion do make exceptions for things like life-threatening scenarios or irreversible physical impairment. Baker said that these vary from state to state, but also that these exceptions are often intentionally vague to dissuade doctors from performing abortions. Doctors may be cautious in making the call that someone has a life-threatening disorder that would allow them to get an abortion, for fear of losing their medical license or being charged with a crime.

Considering EDS is poorly understood, many doctors may decide that the condition is not a good enough reason for a doctor to perform an abortion, Baker said. The guidelines would note that VEDS in particular is life-threatening and, in that way, they could be useful for people with the disease who try to get an abortion in states that have banned it, according to Pezaro.

The extent to which Pezaro’s work could help people with EDS who get pregnant remains to be seen. Merlin Butler is a clinical geneticist and professor emeritus at the University of Kansas Medical Center, and uses genetic testing to identify various diseases, including EDS. He noted that he’s seen an increase in EDS in the past few years. In his opinion, some of the guidelines established could be common across all types of the disease. However, there are mutations in around 20 genes that are responsible for EDS, not including hEDS, for which no gene has been found responsible. As such, the guidelines should ideally be more specific to each variety of EDS, he said. Meanwhile, Blitshteyn noted that the researchers can learn a bit about the complications from the existing literature, but also that the field requires more research, and larger studies.

But Pezaro is hopeful that the guidelines will help doctors, midwives, nurses, and everyone else involved in maternity. McGillis agrees, noting the information provides “more power for patients,” she said. “It’s more power for practitioners to understand how to move forward safely with a pregnancy, or as safely as possible with a pregnancy.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I’d like to share this article but the headline says “rare” which it’s not. So…