Walter Freeman was itching for a shortcut. Since the 1930s, the Washington, D.C. neurologist had been drilling through the skulls of psychiatric patients to scoop out brain chunks in the hopes of calming their mental torment. But Freeman decided he wanted something simpler than a bone drill — he wanted a rod-like implement that could pass directly through the eye socket to penetrate the brain. He’d then swirl the rod around to scramble the patient’s frontal lobes, the brain regions that control higher-level thinking and judgment.

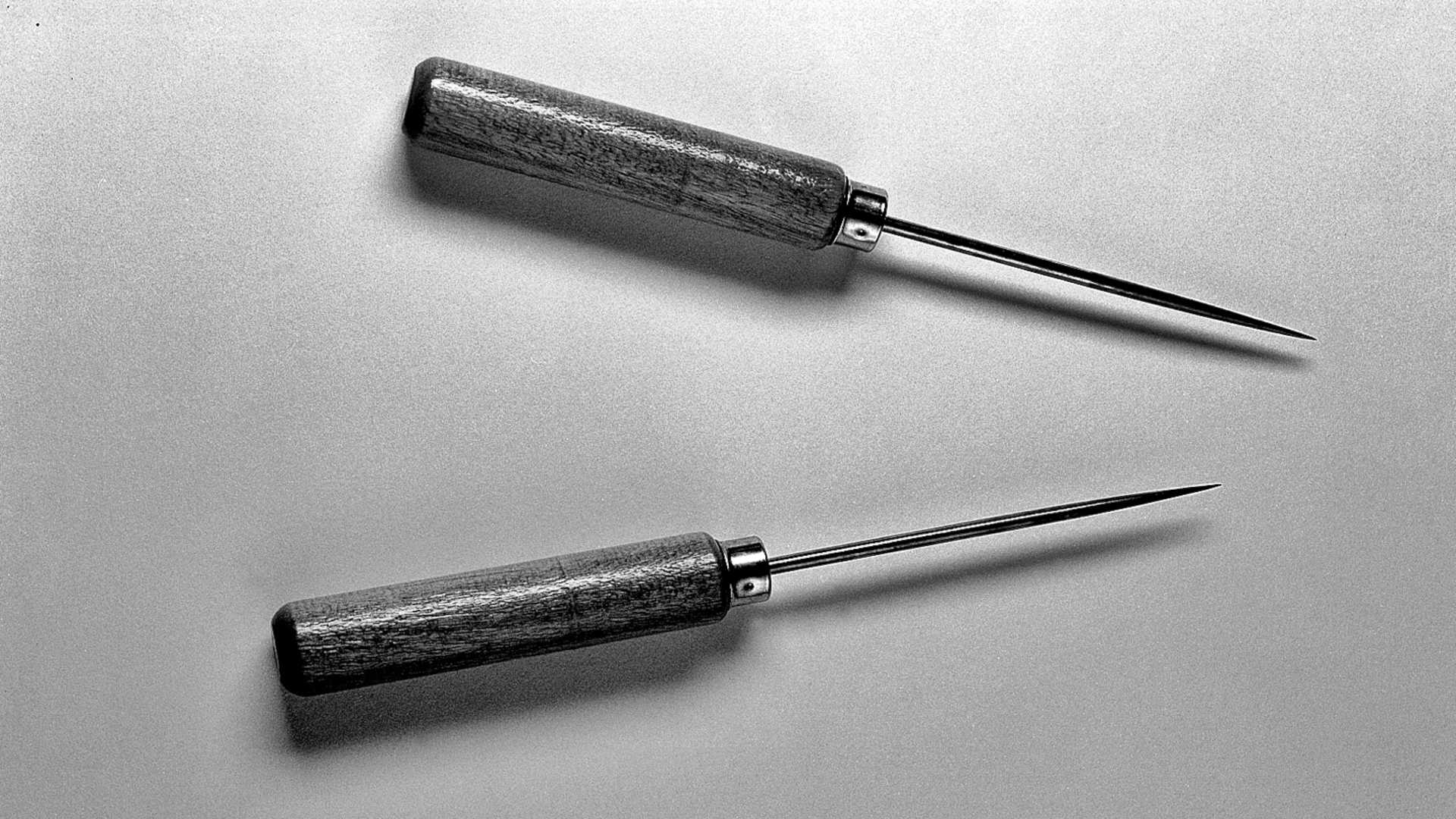

Rummaging in his kitchen drawer, Freeman found the perfect tool: a sharp pick of the sort used to shear ice from large blocks. He knew his close colleague, surgeon James Watts, wouldn’t sanction his new approach, so he closed the office door and did his “ice-pick lobotomies” — more formally, transorbital lobotomies — without Watts’ knowledge.

BOOK REVIEW — “The Icepick Surgeon: Murder, Fraud, Sabotage, Piracy, and Other Dastardly Deeds Perpetrated in the Name of Science,” by Sam Kean (Little, Brown, & Company, 368 pages).

Though the amoral scientist has been a familiar trope since Victor Frankenstein, we seldom consider what sets these technicians on the path to iniquity. Journalist Sam Kean’s “The Icepick Surgeon: Murder, Fraud, Sabotage, Piracy, and Other Dastardly Deeds Perpetrated in the Name of Science,” helps fill that void, describing how dozens of promising scientists broke bad throughout history — and arguing that the better we understand their moral decay, the more prepared we’ll be to quash the next Freeman. “Understanding what good and evil look like in science — and the path from one to the other — is more vital than ever,” Kean writes. “Science has its own sins to answer for.”

Expert at spinning historical science yarns — his last book, “The Bastard Brigade,” was about the failed Nazi atom bomb — Kean presents a scientific rogues’ gallery that’s both entertaining and chilling. Naturalist William Dampier, who influenced Charles Darwin’s work, resorted to piracy to fund his fieldwork in the 17th century. He joined a band of buccaneers that seized gems, scads of valuable silk, and stocks of perfume in raids throughout Central and South America.

A century later, celebrated Scottish surgeon John Hunter worked with grave robbers to obtain bodies so he could study human anatomy. His colleagues emulated his approach, and the pipeline from corpse-snatchers to anatomists continued for decades. The practice was tacitly accepted because it could yield valuable insights — Hunter discovered the tear ducts and the olfactory nerve, among other things — but the human toll was horrifying nonetheless. At public hangings, so-called sack-‘em-up men “sometimes even yanked people off the gibbet who weren’t quite dead yet,” Kean writes. “They’d merely passed out from lack of air — only to pop awake later on the dissection table.”

In a way, though, the gruesome endpoints Kean describes — the scrambled brains, the ransacked ships, the deathbeds — are the least interesting part of his story. They mostly confirm philosopher Simone Weil’s impression that real-world evil is “gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring.”

What’s more compelling is Kean’s take on how the scientists justified their actions. They pushed aside thoughts of collateral damage — the lives they disrespected and damaged — by rationalizing that their contributions outweighed any harm they were doing. Freeman’s work at an early 20th-century psychiatric asylum convinced him of the unalloyed good of calming agitated patients via lobotomy. “The ward could be brightened when curtains and flowerpots were no longer in danger of being used as weapons,” Freeman observed.

But it wasn’t long before the downsides of Freeman’s blinkered strategy showed up. Botched lobotomies killed some patients, while others, like John F. Kennedy’s sister Rosemary Kennedy, emerged unable to speak normally or care for themselves.

Kean excels at conveying each scientist’s slide into corruption — one so gradual that, like the fabled boiling frog, they scarcely noticed they were in hot water. Freeman was once a wunderkind neurology professor, beloved by his students. At some point, he opened a book by Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz and got religion. Moniz claimed excising brain tissue helped end-stage patients recover enough to leave asylums, and Freeman felt inspired to help his own severely ill patients in the same way. At first, it seemed like a reasonable approach of last resort. In Moniz’s midcentury heyday, lobotomies became an accepted part of medical practice at asylums, and Moniz even won the Nobel Prize in 1949 for his advances in psychosurgery.

But then Freeman started performing more and more lobotomies, with fewer ethical misgivings. He increasingly used the crude ice pick to probe patients’ brains, rather than Moniz’s more traditional surgical tools. And he started offering the surgery to adult patients with less severe mental illness and, finally, to young children with mood disturbances. Why not operate as early as possible, he argued, before things had a chance to get out of control?

English naturalist Henry Smeathman likewise began with the highest intentions — he was an ardent opponent of the slave trade. But years later, on a lonely posting to Sierra Leone, he yukked it up with slave ship captains in his free time, then signed on as a slave-trading agent himself. His rationale? By putting his oar in, he could ensure his field specimens got fast passage on slave ships from Africa to England. “Preserving dead bugs and plants meant more to him than preserving his morals,” Kean notes.

Support Undark MagazineUndark is a non-profit, editorially independent magazine covering the complicated and often fractious intersection of science and society. If you would like to help support our journalism, please consider making a tax-deductible donation. All proceeds go directly to Undark’s editorial fund. |

Kean’s catalogue of scientific ne’er-do-wells does have some notable gaps. While he briefly mentions Nazi doctors and their horrifying experiments on concentration-camp prisoners, he skips entirely over early 20th-century U.S. eugenics, a branch of pseudoscience concerned with preserving “fit” human bloodlines and discarding the “unfit.” Founders of this movement, including researcher Francis Galton, in many ways prepared the ground for the genocidal crimes of Adolf Hitler and his henchmen.

Yet Kean makes up for his omissions, at least in part, with the complexity of the portraits he does include. We learn about Smeathman’s respect for his Sierra Leonean guides’ natural history knowledge, and about how carefully Freeman followed up with each of his patients to document their progress. Many unscrupulous scientists, Kean reveals, are far more like us than not. Though it’s comforting to view them as alien, we have many of the same human tendencies they do — and, like them, we have a hard time detecting when the drip-drip-drip of moral compromise turns into a flood.

“Any one of us might have fallen into similar traps,” Kean writes. “Honestly admitting this is the best vigilance we have.”

To avoid such traps, Kean advises scientists to adopt clear ethical guidelines before launching any project, based on research showing that people behave more ethically when they assert their honesty at the start of a task. He also advocates for a technique developed by psychologist Gary Klein and championed by Nobel Prize-winner Daniel Kahneman called the premortem — thorough assessments of all the ways a planned research venture could go awry. But the book stops short of specific policy implications on this score; there’s no analysis of how well scientific premortems might work to forestall future dastardly deeds.

What’s more, some scientists are already so far into the morass that premortems are out of the question. It’s fitting that Freeman’s final surgery, an early 1967 lobotomy, ended in disaster. He failed to aim his pick just right, and the patient sustained a brain bleed and died. No doctor in the U.S. has performed a transorbital lobotomy since — at least, so far as the medical record shows — but lobotomies in general continued into the 1970s. It may be true that, thanks to Freeman’s surgeries, some patients left asylums and returned to their families. But decades later, what is remembered most are the lives the ice pick destroyed.

UPDATE: This piece has been updated to clarify that while the medical literature shows that transorbital lobotomies ended in 1967, lobotomies in general continued into the 1970s.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Thank you for this intriguing review. Regarding the last paragraph, Freeman’s final lobotomy in 1967 was by no means the last one performed. During my research for my book The Lobotomist, a biography of Freeman, I found evidence of dozens of lobotomies performed by other physicians in the 1970s, the last (that I could track down) in 1978.

Thanks for the comment, Jack. We’ve updated the piece to clarify this point.

Is the fix all that better?

What most people consider “lobotomies” still continues under names like Cingulotomy or Ablative Brain Surgery.

Perhaps a better conclusion is that the field has learned from the horrific excesses of the practice and is much more careful now, making such practices last resort and rare.

Although one wonders if scientists and doctors in these fields would have changed, if they didn’t push the lines so far in the first place.