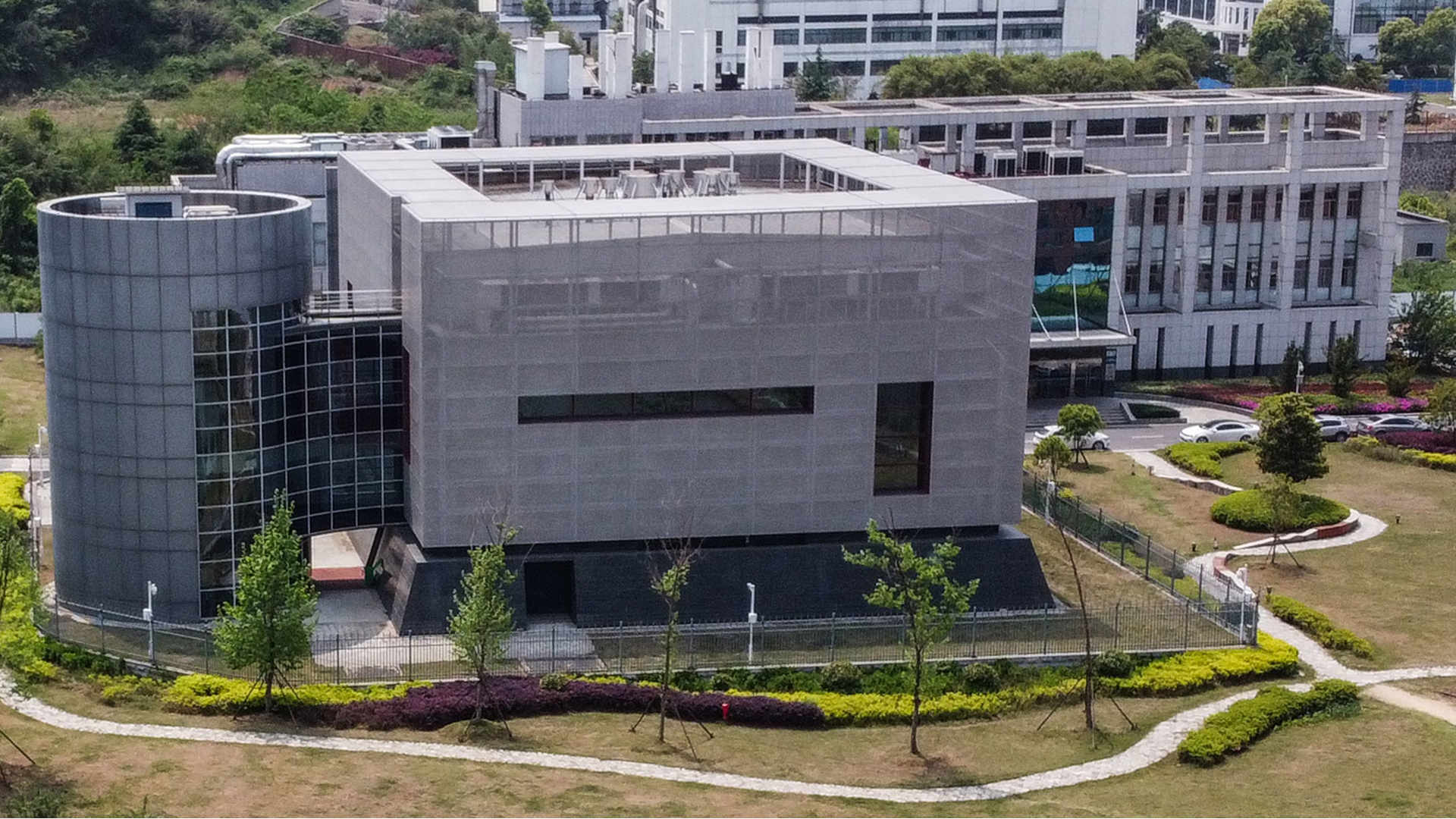

On Sunday, The Wall Street Journal reported that three researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), in China, went to the hospital in November 2019 with symptoms consistent with Covid-19.

The report expands upon intelligence disclosed in January 2021 by the U.S. State Department, which said some Institute employees had displayed symptoms “consistent with both Covid-19 and common seasonal illnesses” that fall, but offered few specifics. And it has fueled suspicions that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, may have originated from within WIV, a high-security facility where researchers study coronaviruses, among other pathogens.

The first cases of Covid-19 were reported near WIV in December 2019. In early 2020, as the coronavirus shut down the world, Republican Sen. Tom Cotton, blaming China for the growing outbreak, began suggesting WIV may have been the source, and laid out several scenarios for a possible origin, including that the virus had been an engineered bioweapon, or that it had escaped during research into pathogens. (He noted that a natural origin was still the likeliest explanation.) Some experts were vigorously skeptical of all lab-leak scenarios — and, in a widely circulated letter published in The Lancet in February 2020, 27 public health scientists described suggestions “that Covid-19 does not have a natural origin” as “conspiracy theories.”

But, as Charles Schmidt reported for Undark earlier this year, some scientists continued to think a lab origin was plausible. (They stressed that such a release would almost certainly have been accidental, and that there’s no evidence the virus was deliberately engineered.) By this past April, even as a much-criticized World Health Organization report declared the lab-origin hypothesis “extremely unlikely,” more American news organizations began to take the possibility seriously.

The kind of intelligence reported in The Wall Street Journal this week may have catalyzed an even stronger response. On Wednesday, President Joe Biden announced that the U.S. intelligence community considers a lab leak one of “two likely scenarios” for the origin of the pandemic, and said he asked officials to provide a report to the White House in 90 days.

The question of Covid-19’s origins may not be resolved for years, if ever. But, already, the new attention to the lab-leak hypothesis has triggered a backlash from China, which disputes that SARS-CoV-2 escaped from one of its labs. (The Chinese embassy in the U.S. issued a statement this week complaining that both a “smear campaign and blame shifting are making a comeback” and describing the lab-leak hypothesis as a “conspiracy theory.”) The latest revelations have also set off recriminations within U.S. media as to why many left-leaning outlets were so quick last year to dismiss the lab-leak hypothesis as a crackpot theory.

Perhaps the biggest question, though, is about the implications for scientific research. For years, some scientists have expressed concerns about safety procedures in laboratories studying dangerous pathogens. For months, many researchers and analysts in the U.S. have believed that it’s at least plausible that one of those safety lapses unleashed a virus that has killed millions of people worldwide. As that theory gains traction — and those long-standing concerns gain unprecedented public attention — the consequences for research policy remain unclear.

Also in the News:

• As the planet rapidly warms, activists and investors are taking new steps to hold oil and gas companies to account for their contributions to climate change. Activist investors this week won an election to take over two seats on the board of Exxon, despite attempts by the oil giant to convince shareholders to vote against them. At Chevron’s board meeting, 60 percent of shareholders voted in support of a resolution asking the company to reduce emissions. And on Wednesday, a court in the Netherlands ordered Royal Dutch Shell to make dramatic cuts to its greenhouse gas emissions, demanding a 45 percent decrease by 2030. The court said that the company’s existing plan to reduce emissions was too vague and marred by conditions and loopholes. Although Shell immediately announced it would appeal the decision, environmentalists hailed the ruling, saying they hoped it would set a precedent for similar court actions against fossil fuel companies in other countries. The Dutch branch of Friends of the Earth, an international environmental group, brought the case in the Netherlands. “This ruling will change the world,” the group’s lawyer, Roger Cox, said after the decision, according to The New York Times. The ruling could shrink Shell’s energy output by 12 percent, business analysts reported this week. (Multiple sources)

• In Wisconsin, an unlikely hero may be preventing cars from hitting deer: the gray wolf. This is according to a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. As The Atlantic reported this week, the study examined more than two-decades-worth of data in Wisconsin and estimated that the wolves have cut deer-related car crashes by 24 percent and saved the state $10.9 million a year. If the findings hold up, that’s quite a reduction: Even with the wolves, an average of 19,757 people hit deer in the state each year, with an average of 477 injuries and 8 deaths per year between 2014 and 2018, according to state statistics. The findings come amid ongoing debate in Wisconsin over the hunting and trapping of wolves. Some outside experts expressed skepticism of the study — a large-carnivore researcher from Sweden, for instance, told The Atlantic that the authors didn’t reveal enough about their “statistical methods, the degree of uncertainty in their results, or details on how to replicate their analysis.” While lead author Jennifer Raynor, an economist at Wesleyan University, conceded that the work had limitations, she maintained that the wolves are making a difference: “Some lives are saved, some injuries are prevented, and a huge amount of damage and time are saved by having wolves present.” (The Atlantic)

• A software engineer claims that China has installed AI-enabled emotion detection software in police stations in Xinjiang province. Some 12 million Uighurs, a largely Muslim ethnic minority, live in the northwestern province, where they are subject to intense government surveillance, detention in a vast network of internment camps, forced birth control and sterilization, and other abuses that have led the U.S. State Department to accuse the Chinese government of committing genocide. The engineer, who spoke with the BBC on condition of anonymity, produced images of five Uighur detainees who were tested using the software. According to the engineer, officers physically restrain detainees and force them to look into a camera. The camera, equipped with AI-enabled software, picks up small facial expressions and features on the skin, and then generates a pie chart with a section that, the BBC writes, represents a subject’s “negative or anxious state of mind.” (It’s unclear whether the tool can actually produce accurate assessments of subjects’ emotions.) According to Darren Byler, a researcher at the University of Colorado, Boulder, Uighurs are regularly subjected to such granular surveillance in Xinjiang. “Uighur life,” he said, “is now about generating data.” (BBC News)

• And finally: The social sciences have long struggled with a reproducibility crisis: Many of the field’s big experimental findings, particularly in psychology, have buckled under scrutiny, with findings that turn out not to replicate when other groups repeat the experiment. Now comes new evidence that these unreliable studies are, on average, more popular than their counterparts — and they remain so even after their flaws have been documented. In the new study, economists at the University of California, San Diego, tallied citation counts for dozens of social science papers that had been subjected to independent replication attempts. Papers that failed to replicate racked up, on average, 153 more citations than those that didn’t. Even after the failed replication attempts, the citation bump persisted, with only around 12 percent of the citations acknowledging the replication failure. Those results dovetail with previous work that has shown, for instance, that studies published in more popular journals are more likely to be retracted. But psychologist Brian Nosek, who has spearheaded several replication projects, sounds a fitting note of caution: Before taking this newest result too seriously, he told Science, it’s worth seeing whether it, itself, can be replicated. (Science)

“Also in the News” items are compiled and written by Undark staff. Deborah Blum, Brooke Borel, Sudhi Oberoi, and Ashley Smart contributed to this roundup.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

You guys were ahead of that one. Well done.