In November 2012, Katherine E. Standefer was in her late 20s and playing in a soccer game in Colorado when she was shocked by three invisible bolts of electricity: “A maul cracked open my chest with a sickening thump, a hot whip tearing through my back.” The source of the shock was not lightning but her implanted defibrillator, and that harrowing experience inspired her to investigate the origin of the device that was intended to save her life.

Standefer’s debut memoir, “Lightning Flowers: My Journey to Uncover the Cost of Saving a Life,” is what medical sociologist Arthur Frank would call a chaos narrative: a story of illness in which “troubles go all the way down to bottomless depths,” and “what can be told only begins to suggest all that is wrong.” Chaos narratives can be uncomfortable to read, because they expose a fundamental powerlessness over bodies and lives, in contrast to the narrative of progress, professionalism, and technological triumph that undergirds much of modern medicine. But chaos narratives are also deeply real, reflective of life’s messy interdependencies, and have the power to expose the flaws in the systems that shape and regulate human life.

BOOK REVIEW — “Lightning Flowers: My Journey to Uncover the Cost of Saving a Life,” by Katherine E. Standefer (Little, Brown Spark, 288 pages).

Beginning with the author’s discovery of a likely genetic heart condition in her early 20s, “Lightning Flowers” branches outward, like the delicate scars of actual lightning strike victims, as she explores the personal, ethical, environmental, and economic implications of the medical care she received. There are complications at every turn, and no easy answers or resolution, but her journey is filled with moments of personal growth, mindfulness, and attention to nuance.

Both Kati, as her friends and family call her, and her younger sister discovered they had a rare genetic heart mutation called Congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS) after fainting spells. The condition gets its name from the five electrical pulses that the heart generates to power its regular beat; cardiologists have named them P, Q, R, S, and T. The P pulse moves oxygen-depleted blood through the upper chambers of the heart to the ventricles. Q, R, and S pump blood from the ventricles to the lungs for oxygenation and then out to the rest of the body. T is the electrical pulse that resets the heart to do it all over again. For those with LQTS — about one of every 2,000 to 5,000 individuals — the heart takes longer to reset for its next beat. This can cause sudden life-threatening arrhythmias, or abnormalities in heart rate or rhythm.

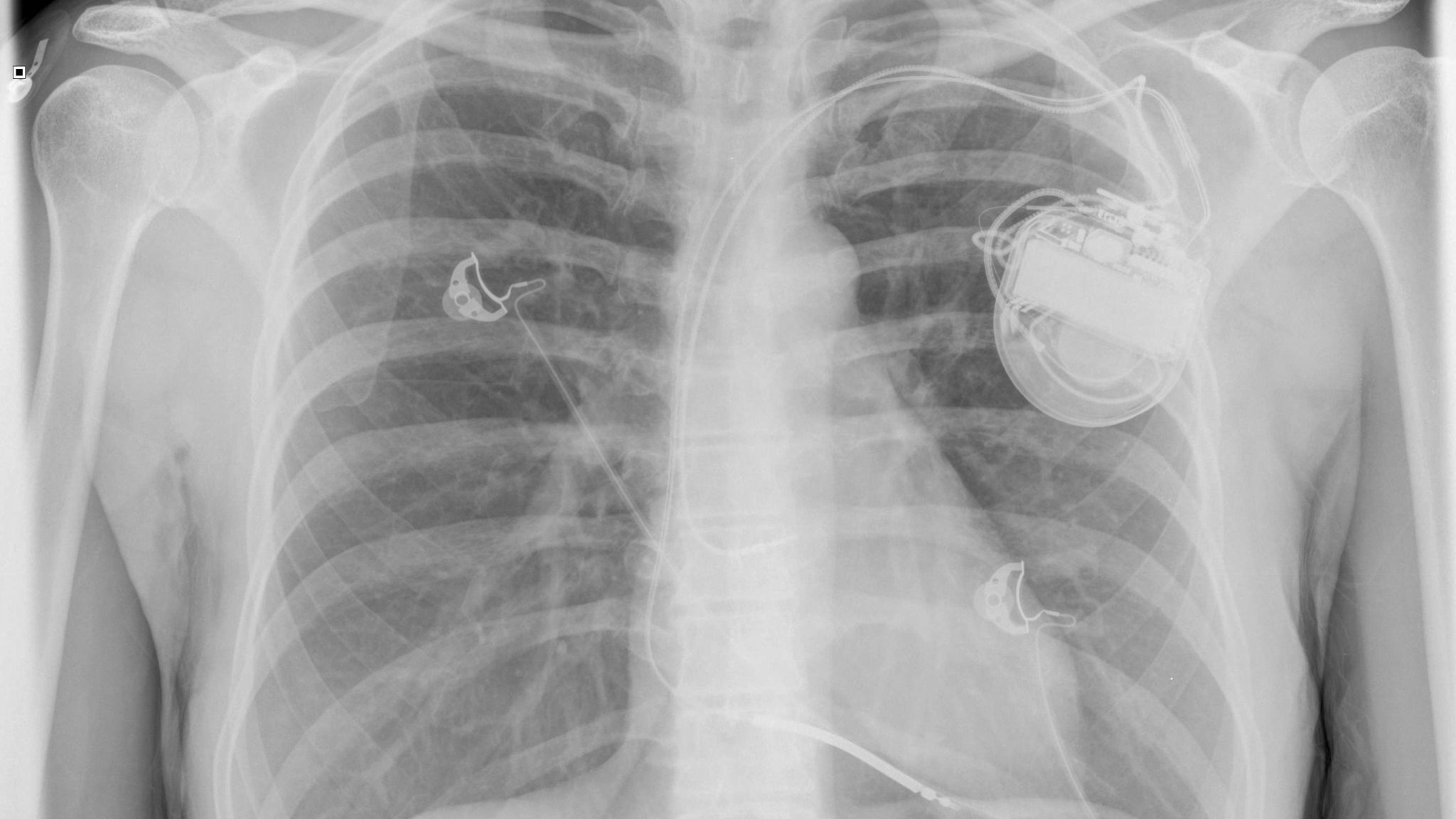

After an unsuccessful attempt to use beta-blocker medication to keep her heart rate artificially low, Standefer’s doctors strongly advised her to get an implantable electronic device related to the pacemaker — an cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). ICDs monitor the heart and administer electric shocks, as needed, to jolt heartbeats into a regular rhythm. The implantation surgery would require carving a pocket into her left pectoral muscle to accommodate a small titanium box, containing a motherboard, capacitor, and battery, which is attached to her heart by a wire threaded through a major vein.

Setting aside the apparent impossibility of paying for the surgery — she had no health insurance, and it was 2009, pre-Affordable Care Act — Standefer didn’t like the idea. “The thought of having a computer placed in my body panicked me,” she writes, “It was the idea of becoming a technological person. It was the idea that a human was a series of systems, and any one of them might be replaced by technology, that my human problems would now be tech problems.”

Further complicating her decision, Standefer, a journalist and environmentalist, was concerned about the resources required to make an ICD and the human and environmental cost of their extraction. In college, she had visited a mine in Questa, Mexico, which sold molybdenum, an ingredient in some steels, to the Department of Defense. While there, she witnessed the mine’s devastating impact on health in Questa, where “the hair of the children turned white. Their fingernails streaked white. White blobs poured from the faucets.” As a result, she was distressed by the need to implicate herself in such destructive supply chains by purchasing an electronic device made of titanium, cobalt, nickel, and other metals.

Nonetheless, she decided to proceed with the surgery. She moved from her home in Jackson, Wyoming to Boulder, Colorado, where a doctor agreed to waive his surgical fee and she could take advantage of an Indigent Care Program that helps cover medical costs for Colorado residents who can’t afford them.

Three years after she got the surgery in 2009, the searing shocks from her ICD ignited her concerns about the materials in the device, and she set out to investigate the dynamics of extractive industries and the global supply chain for microelectronics. “I wanted to know whether the thing in my body was worth making,” she writes. “That my life was worth what it took.”

Discovering that mining is lucrative for mine owners and investors but tends to inflict a litany of negative effects on workers and people living nearby, as well as on the environment, Standefer began visiting mines owned by companies with social responsibility programs in place.

In Madagascar, she visited a cobalt and nickel mine that had required the removal of a village and the destruction of a forest ecosystem home to unique endangered species. She observed first-hand the mining company’s sustainability efforts, including rehoming lemurs and other animals to a designated protected forest corridor, buying local food, and building HIV prevention programs. Despite the efforts, she also witnessed how unevenly the mine’s economic gains are distributed and the deep challenges of restoring a decimated forest. In Rwanda, she was charmed by a certified conflict-free mine but cautioned by locals that “things are rarely as they look.”

It didn’t take long for Standefer to realize her search for sustainable mining was a hopeless endeavor, that there would be no neat calculations of good vs. bad, no clear answers. Each “solution” generates new problems, and there is always “some other factor, some unintended consequence” complicating even the most thoughtful and well-resourced attempts to mitigate the destruction wrought by industrial mining. Furthermore, she discovered that the destructive industrial mining systems produce much more than medical devices, including thousands of other metal products and by-products, including smartphones, laptops, toothpaste, and white paint.

Meanwhile, Standefer’s own health becomes increasingly unmanageable. Coping with sepsis, malfunctioning devices, a crunched internal wire, and failed surgery, her search for appropriate and effective treatment is hampered by labyrinthian bureaucracy and precarious insurance coverage. This, she notes, is far from the typical trajectory of a medical memoir, in which a well person gets sick, receives treatment, and becomes well again.

Standefer’s chaos narrative builds to a systemic indictment of industries that poison the earth and its inhabitants, and of a medical system that makes it so difficult for people to receive necessary care and mars the lives of those who receive poor treatment. But ultimately, she is unable to fully resolve the tension at the core of her memoir: the question of whether her life is worth the metal extracted from the earth to save it.

Nonetheless, she manages to conclude on a hopeful note: her belief that we can envision an equitable, compassionate society through innovation: “We have more power to create something different than we are willing to admit.”

Jordana Rosenfeld is a freelance writer based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, whose writing has appeared in The Nation, GQ, Jewish Currents, and PublicSource, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I’m surprised the author didn’t make the connection to the rise in mining for similar metals needed to create renewable energy infrastructure, a rise which will undoubtedly create a lot of environmental destruction, societal displacement and severe health problems for miners and local people. The mining industry is publicly salivating over the prospect of Green New Deals in the USA as elsewhere.