The Bärengraben, or bear pit in Bern, Switzerland, rests beneath a rose garden, at the foot of Nydegg bridge. It abuts the mint green Aare River, which swoops in a horseshoe bend around the city’s medieval Old Town. When I first visited it as a 6-year-old, 24 years ago, it was little more than a drab fortified pit, roughly 108 feet wide and 11.5 feet deep, inhabited by 12 bears. I can still feel the sting of winter and the warm wafting scent of roasted chestnuts emanating from the nearby vendor, who also sold carrots for the bears. I squeezed the carrot I was given, imbibing it with well wishes for the bears, and tossed it down, as so many generations of Bernese had done before me. But even as a child, I sensed that these 450- to 750-pound wild animals should have been bounding in the green abundance of the Swiss Alps, not in a concrete hole in the ground.

From the city’s oldest heraldic crest — which features a prancing bear — to its bear fountains to its cuddly tourist teddies and baked goodies, the Bernese love their bears. The legends I heard growing up held that the city was founded in 1191 by Bertold V of Zähringen, who derived the name Bern from the Germanic word bären, meaning bear, after a successful bear hunt. Bears have been a part of Bernese culture ever since.

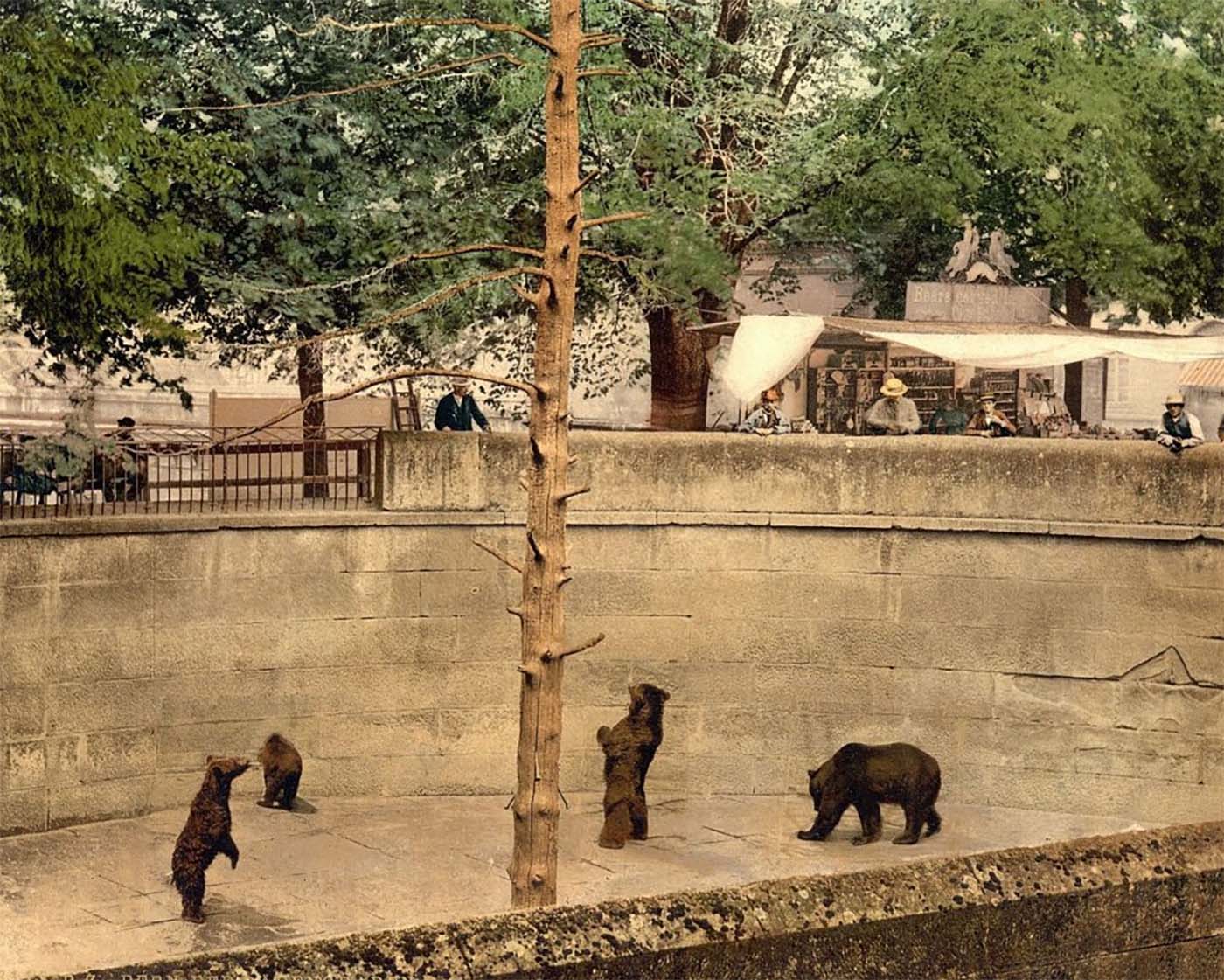

As early as 1513, the city has kept live bears on display. The first captive bear was a war spoil from the battle of Novara. The Bern Bear Park says the first recorded mention of live bears in the city came from chronicler Valerius Anshelm, who noted the bear was placed in the moat by the original medieval city gate and prison.

Predating the modern concept of zoos, the original bear enclosure was never designed to be educational or part of conservation efforts to preserve bears. It was a statement — a symbol of the fierce Bernese who fight like bears.

Bears became a central part of the city’s cultural identity and are still pictured today on the official flag. The pit I recall from my youth was built in 1857. It had a concrete floor and a few trees. And it had developed into a popular tourist attraction. Even Albert Einstein, who lived in the heart of Old Town from 1902 to 1909 while working at the Swiss patent office, would have visited the Bern Bear Pit.

But, like other public animal exhibits, the pit was fraught with moral conflicts. Bears are intelligent creatures and need large naturalistic spaces with constant stimulation. Bears kept in dismal conditions exhibit unnatural stress behaviors like pacing and swaying. The Humane Society of the United States says the minimum requirements for captive bears are a large home — measured in acres, not feet — with natural ground to dig, boulders and trees to climb, pools for swimming, caves to nest, a varied diet, and opportunities to forage and hunt. A male brown bear claims a range of 200 to 500 square miles; the pit was a paltry 6,786 square feet.

The ethical issues surrounding the Bern Bear Pit speak to a broader dilemma faced by virtually all zoos. Zoos and aquariums are contested places. On one hand, they are regarded as places of learning and conservation; on the other, places of cruelty. They may exploit their denizens, but they can also inspire future generations to protect endangered animals. Carl Safina, an ecologist, wrote in the Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science in 2018 that “in reality, there is a range — a range of zoos and a range of concern about animals — within continually changing societal values and environmental realities.”

In the 1980s, Bern’s societal values began to noticeably shift, albeit slowly, as animal welfare became increasingly important. The Swiss Animal Protection Ordinance passed in 1981, establishing, among other things, minimum requirements for animal enclosures. Animal rights activists grew unamused by assertations like this one, from a 1993 Bern tourism book: “[The bears] love getting the biscuits, nuts and carrots that spectators throw down to them and show their thanks with amusing begging scenes and acrobatic acts.” Local and international visitors deemed the pit sad and small, a dungeon and a shameful relic of the past.

Between 1994 and 1996, the bear pit was retrofitted with softer gravel grounds, a swimming pond, a cave, and a hill of stone blocks that created shade. Yet, it remained an uncomfortable controversy for Bernese caught between a cultural icon and modern animal rights.

When the Swiss government, which sits in Bern, twice refused to discuss animal rights legislation at the end of the 20th century, citizens said fertig! — enough is enough! In 2000, more than 100,000 people petitioned the Swiss government to recognize animals not as “things” but as sentient living creatures, with rights to dignity and freedom from pain. To their dismay, the government rejected the proposal.

In 2002 however, as more complaints regarding the dismal bear pit reached Bern’s tourism office, the Swiss government passed a law deeming animals to be living entities with legal rights. A year later, the city of Bern hosted a design contest for a new bear facility. The newly christened Bären Park, or Bear Park, opened in 2009. Larger than a football field, the 64,500-square-foot space rests on the grassy hill next to the old pit.

When I returned to Bern in 2014, I met a new generation of Bernese bears, Björk and Finn. The bears now gaze toward the Aare River and Old Town. The naturalistic enclosure features tunnels for winter naps, trees to climb, and an opening to the river to swim and catch fresh fish.

In his 2018 article, Carl Safina wrote that “though we no longer need wild animals, wild animals now need us … There is real danger that wild animals and wild places will come to seem irrelevant.” Those observations certainly ring true in Switzerland.

Hunted to extinction in 1904, there are no native bears in Switzerland today. The country’s ancient forests have given way to neatly organized cities. Humans have transformed all wild corners of the country. In 2017, a wild bear wandered over the alps into the canton of Bern for the first time in 190 years. According to the Carnivore Ecology and Wildlife Management organization, Switzerland overall has had at least 11 wild bears visit since 2005. Many met unhappy ends from new human hazards like trains and freeways, or were killed for being perceived as hazards themselves after breaking into homes or hunting livestock. Places like the Bear Park offer the only chance for Swiss to observe their once native bears.

The Bear Park’s new mission advocates “more space for fewer animals,” but zoos must go beyond such statements. They must continuously evolve in animal management and not just preach conservation, but practice it. It’s the fundamental responsibility of zoos to be a sanctuary; conservation for animals and our planet must be the leading factor in decision-making. Zoos must walk their talk.

So, too, must the public. We, as a society, have a responsibility to speak up and vote for animal welfare laws — and to vote with our dollars (or francs). We must research and choose to visit zoos that are accredited. In the U.S., the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) offers guidance: Zoo websites and entrances will typically display accreditation status with the AZA. For those who are traveling, the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) lists over 400 accredited organizations, including the Bern Bear Park.

I believe zoos can have a place in modern society if they shift from entertainment centers, like the disreputable “Tiger King” facility, to wildlife sanctuaries that invest in their animals. The Bern Bear Park shows us what is possible. When my children visit the new Bear Park, I’m glad I can tell them a story of changed perspectives, of growth towards better animal welfare rooted in science and compassion. Without doubt, it is a better zoo than it was 24 years, or even 500 years ago. But it remains up to each of us to help good zoos continue the journey to becoming great ones.

Annabelle Moore is a freelance science writer. She has written for humanitarian and science nonprofit blogs and enjoys exploring the wild, wonderful world of the American Southwest.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I visited Bern a couple of years ago, and was appalled to see these beautiful bears being stared down upon by tourists. Even speaking to a couple of residents, they too would have preferred the bears get taken care of in a sanctuary, away from the prying eyes of tourist.