The Problem With MRIs for Low Back Pain

Like all primary care physicians, Danielle Ofri sees a lot of aching backs. Low back pain is one of the top five reasons people visit the doctor, and based on extensive experience, Ofri knows how the conversations will go. Patients want relief from miserable pain, so they want an imaging study. “I want to see what’s going on — that’s what they say,” says Ofri, who treats patients at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan.

The easy thing to do is order a scan and send them home to wait for the results. The right thing to do, in the vast majority of cases, is to deliver the bad news: They need to wait for the pain to subside on its own, which may mean a few weeks of agony. In the meantime, if possible, it’s best to stay active and limit bed rest. An over-the-counter pain reliever might help. Unless certain symptoms point to a more serious problem, the physician shouldn’t order any imaging within the first six weeks of pain. On this last point, medical guidelines are remarkably clear and backed by studies demonstrating that routine imaging for low back pain does not improve one’s pain, function, or quality of life. The exams are not just a waste of time and money, physician groups say; unnecessary imaging may lead to problems that are much more serious than back pain.

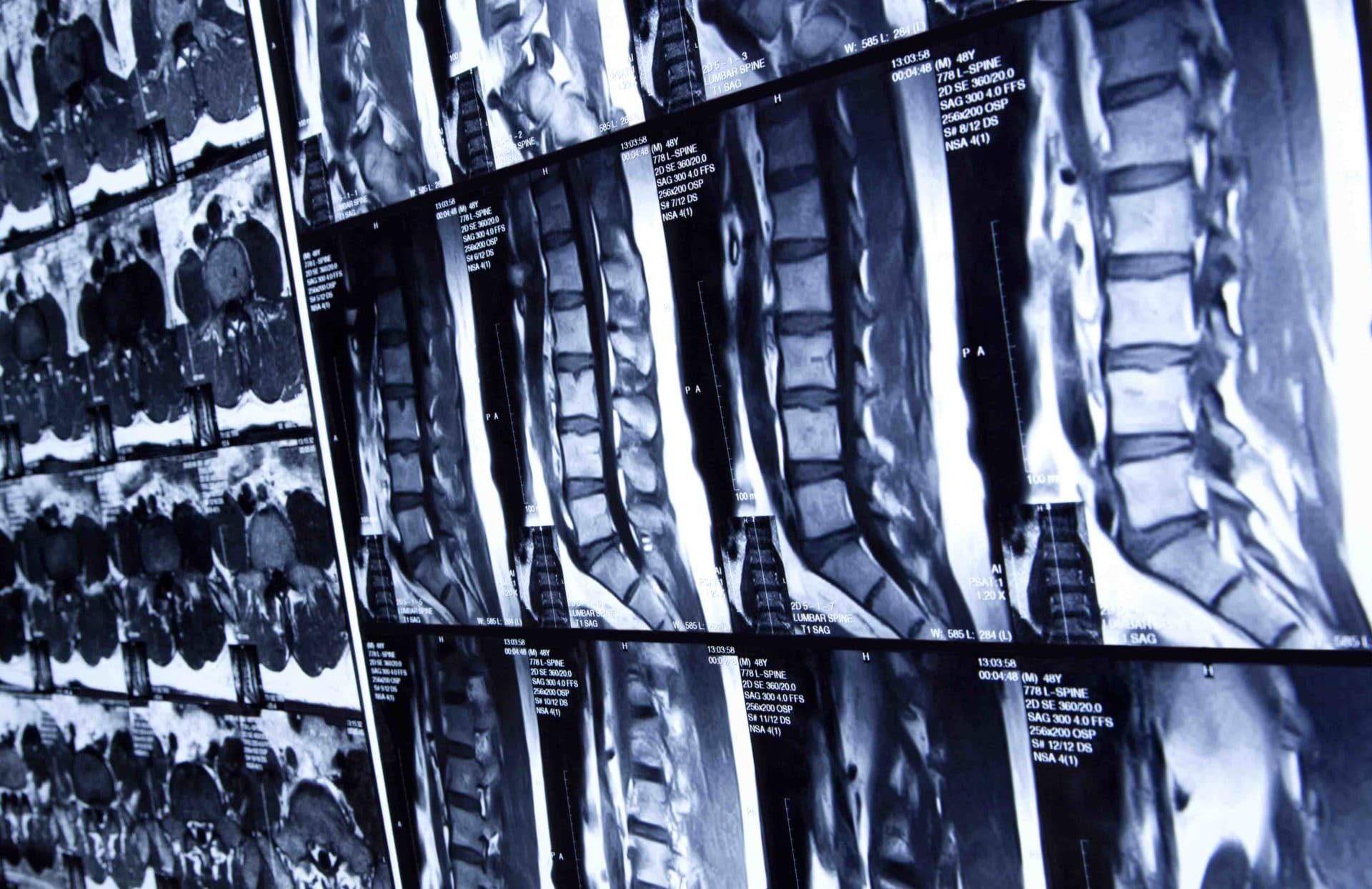

And yet, between 1995 and 2015, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and other high-tech scans for low back pain increased by 50 percent, according to a new systematic review published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. According to a related analysis, up to 35 percent of the scans were inappropriate. Medical societies have launched campaigns to convince physicians and patients to forgo the unnecessary images, but to little avail.

It’s a symptom of a well-diagnosed problem: the overuse of medical services. Unnecessary imaging isn’t confined to just low back pain. Americans spend more than $100 billion on various types of diagnostic imaging each year, much of which is unnecessary and potentially even harmful. F. Todd Wetzel, past president of the North American Spine Society, identifies the problem as “the technological tail wagging the medical dog.” After MRI and computed tomography (CT) emerged in the 1970s, many physicians started routinely using scans to make a diagnosis for low back pain, rather than using them the way they’re intended to be used: to confirm or refute an uncertain diagnosis.

Overuse of diagnostic imaging was crystal clear a decade ago, but medical practice changes slowly. Conventional wisdom suggests that, on average, it takes 17 years for new medical knowledge to be incorporated into practice. Arthur Hong, an economist and primary care physician at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, has studied inappropriate imaging for low back pain. He says public health campaigns — think about smoking cessation, for example — move slowly. “It’s taking a long time and we’re not there yet, but it’s a worthy effort,” he says. “We’ve got to keep trying.”

Low back pain is a major health care headache in part because it’s so common. At least 60 percent of U.S. adults will experience it during their life and more than 30 percent report experiencing low back pain the preceding three months. In the U.S., an estimated 264 million work days are lost every year because of back pain.

Cheryl Clay, a recently retired office worker in Springfield, Missouri, hurt herself when she picked up a case of soda 40 years ago and she has suffered low back pain on and off ever since. “It’s a throbbing, aching pain and when it flares up, it’s a consistent ache,” she says. “It’s like it is locked — like my back is trying to bend but it is locked halfway.”

Clay is hardly alone; recurring back pain episodes are common. Not surprisingly, many sufferers end up in a doctor’s office. According to medical guidelines, the physician should examine them for red flags that suggest infection, fracture, or another urgent problem. If none are seen, the cause of the patient’s pain is most likely muscle strain, herniated disc, or degenerative disc disease, a term that describes the signs of wear and tear on the spinal discs as they age, says Wetzel, who is chief of orthopedics at Bassett Medical Center in Cooperstown, New York.

“Ninety percent of patients with low back pain will respond to things like medication and goal-directed physical therapy, and they do not need imaging at all,” Wetzel says.

Physicians say there are good reasons to avoid imaging. Though X-rays are inexpensive, they zap a patient with radiation, which may raise one’s risk of cancer. (High doses of X-rays are known to cause cancer in humans, but the carcinogenic effect of exposure to radiation at the low doses associated with medical imaging is not well supported; still, the average radiation from a spinal X-ray is 75 times higher than that from a chest X-ray, leading medical guidelines to caution against unnecessary exposure.) CT scans also use radiation and are more expensive.

But the biggest problem, say physician groups, is the MRI. While this technology doesn’t use radiation, it is expensive and can actually provide too much information. David C. Levin, a radiologist at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, explains: “If you took a whole bunch of people who had no symptoms and did MRIs of their low back, you’d find all kinds of disc herniations and protrusions and all sorts of other things that really aren’t causing symptoms.” The majority of adults over 60, for example, have some disc degeneration — but it may not be the cause of low back pain.

MRIs frequently lead to surgery for benign abnormalities, says Wetzel, who has researched why back surgeries so often fail to alleviate symptoms. “The MRI provides so much information that oftentimes it’s difficult to realize that much of it may be irrelevant to the problem that brought the patient to your doorstep,” he says.

MRIs of the lower spine also detect abnormalities on nearby organs. Adrenal glands, Levin says, are notorious for having cysts that, in the end, won’t cause any problems. But once a radiologist spots even a small mass on the adrenal gland, it has to be reported to the primary care doctor because it could be cancer.

That will likely lead to more tests which, in turn, may find more potential problems that may or may not be something that actually needs attention. And anything that leads to surgery puts the patient at additional risk. A recent study of so-called low-value hospital procedures found that spine surgeries for uncomplicated low back pain were associated with high rates of hospital-acquired complications, infections being the most common.

The researchers’ conclusion: use of low-value procedures “in patients who probably should not receive them is harming some of those patients.”

The idea that patients receive medical procedures that physicians consider unnecessary, wasteful or “low-value” may seem strange — unless you work in health care.

Nearly a decade ago, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) estimated that 30 percent of health care spending is wasted. Other estimates have ranged from 27 percent to more than 50 percent; an analysis published last year in Health Affairs said that “wasted spending now comfortably exceeds $1 trillion annually.”

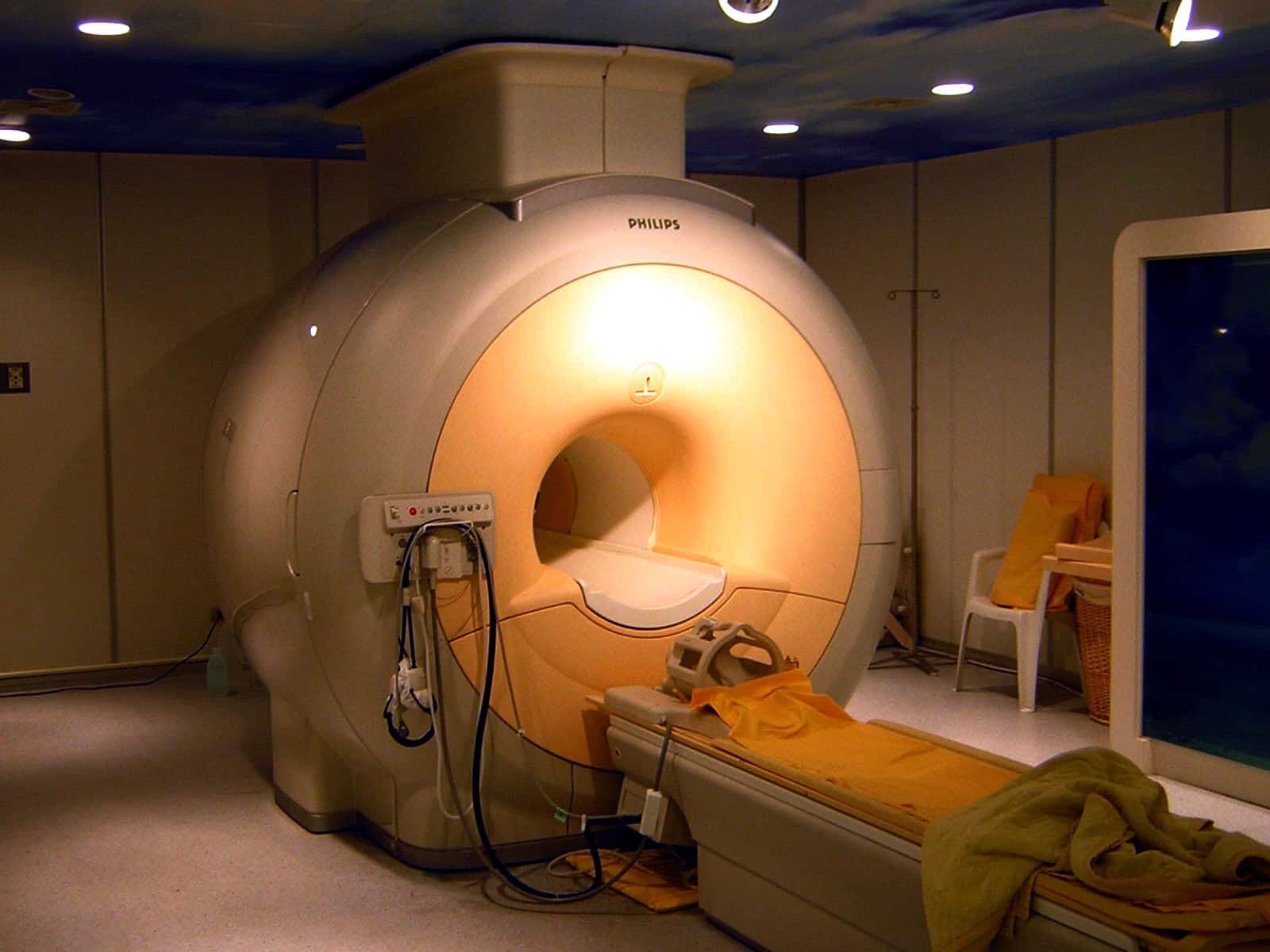

MRI machines, like the state-of the-art model at Tri-Service General Hospital in Taiwan shown here, often provide too much information that may not be relevant to people suffering from low back pain.

Visual: KasugaHuang / Wikimedia Commons

That waste includes excessive administrative expenses (for medical documentation and billing, for example) and fraud, but every calculation includes a healthy dose of “unnecessary services.” The Health Affairs researchers estimated that roughly $241 billion in 2016 was wasted on overtreatment.

To chip away at that, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation launched the Choosing Wisely initiative in 2012 with the goal of reducing unnecessary medical tests and treatments. The idea is that each medical society identifies a list of the top five “overused” tests and treatments in its specialty and encourages its physicians to mend their ways. Items on the list are by no means verboten; rather, items on a society’s Choosing Wisely list deserve careful consideration rather than a quick decision.

Some 80 medical specialty societies have since called out more than 540 low-value tests and treatments. Imaging for low back pain might be the most popular target. Eight specialty societies — including two of the largest, the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians — have tagged imaging for low back pain as an overused service.

So far, the campaign has not been a rousing success. In the first two-and-a-half years after Choosing Wisely started, inappropriate imaging for back pain dropped just 4 percent, according to Hong’s research. He looked at imaging in the U.S., where Choosing Wisely got its start. The campaign has since spread to 20 countries around the world. Earlier this year, a research team reviewed 45 studies of low back imaging rates in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand between 1995 and 2017. During that time, one in four patients who visited a primary care doctor complaining of back pain received imaging. For those who visited an emergency room, the numbers were one in three.

“The rate of complex imaging appears to have increased over 21 years despite guideline advice and education campaigns,” the researchers said.

Why does inappropriate imaging remain so common? Research points to a number of factors, including what is, for many physicians, a paradox. “It’s hard to be responsible for taking care of folks and then only tell them the things you’re not going to do for them,” says Hong.

Financial incentives can prompt physicians to provide unnecessary care, and physician ownership or investment in imaging facilities is associated with higher rates of imaging. But physicians working in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system, which provides low- to no-cost health care to more than 9 million enrolled veterans and their families, do not have financial incentives for ordering wasteful images — and yet a nearly a third of the MRIs they ordered for low back pain in a single year were inappropriate. When that was discovered, a research team set out to figure out why these scans were being ordered. The researchers asked nearly 600 VA physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants what they would do with a hypothetical 45-year-old woman — low back pain, no red-flag symptoms — who was asking for an MRI or a CT scan.

Only 3 percent thought the scan was a good idea and 77 percent said they would worry that imaging would lead to unnecessary tests or procedures. But clinical judgment wasn’t the only thing on their minds. More than half the clinicians thinking about the hypothetical patient feared that she would be upset if she did not receive imaging and that Choosing Wisely recommendations would not be persuasive. “Many patients don’t feel as though they’re getting an appropriate evaluation for back pain unless they have an MRI,” Wetzel says.

And more than a quarter worried they would be leaving themselves open to a malpractice claim if they didn’t order the test. “It’s easier to follow the path of least resistance,” Levin says. “Let the patient go get an MRI and then see what happens.”

Hong was a resident physician at Mayo Clinic several years ago when a radiologist came to see him complaining of low back pain. During the examination, he found no red flags, and the patient volunteered that he knew the imaging guidelines for the situation.

“But he felt so terrible, and his back was so painful, that he just kept asking me in kind of a weird way,” Hong remembers. “I finally picked up on it: ‘Oh, this guy is asking me for an X-ray of his back. And it’s because he just wants something done.’”

People in pain may not be receptive to a conversation about wasted health care spending and medical guidelines that would let them suffer for six weeks before getting an image. Ofri often opts to discuss the potential risks of radiation exposure, which prompt patients to back off their requests for a scan. Sometimes she discusses a likely root cause — too much weight in the abdomen or poor lifting technique — and urges patients to make lifestyle changes to avoid back pain episodes in the future. She sympathizes that it isn’t really what they want to hear. “Patients just want to feel better,” Ofri says. “The situation is not very satisfying.”

Lola Butcher is a health care business and policy writer based in Missouri.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I agree with you

Well when you have a thorasic injury that is ongoing for years from a work related injury that is diagnosed as just a sprain.MRI is the only proof you have unfortunately when physios and doctors are to scared to admit what it maybe because work cover want to save money resulting in a more severe injury.I agree scans dont help pain but they help what you are entiled to financially which to me is worth it considering I would have to pay for future treatment if needed.

Not so much an exercise but a mostly static, under tension posture on the floor for just a short time. Send me an email and I’ll explain it to you. mpatin [at] ameritech.net

Many early scans are attorney or employer/insurance adjuster driven.

I am a retired FP and occupational medicine doc. That means I saw lots of back pain. I am also a back pain suffer.

My approach to back pain patients requesting imaging studies I thought unnecessary was to explain the expected symptoms with a herniated disk. Many realized they didn’t have the right symptoms and decided they didn’t want the imaging study. I also explained the primary reason to do imaging – to determine if the person needed surgery. With this information, most patients decided they didn’t want the study.

I also found it useful to use my “crystal ball” and predict the person’s symptoms before they told me. I would say your pain is worse when first get up, gets better as the day goes on, and then increases in the evening. Laying down lessens the pain, but it’s painful when getting up. And so on. When I was done they patient would say, somewhat amazed, “How did you know that?” My answer, “That’s typical for muscular back pain.”

Education helps as does drawing the patient into the decision-making process.

Of course if MRI’s and other imaging were priced APPROPRIATELY, it wouldn’t be such a big deal; when something has a wholesale contract price of $300 but a ‘retail’ price of $3,500, it is market distortion to say the least.

This won’t resolve until we get the GOVERNMENT out of health care; they protect the insurance companies in numerous ways, from concealing the premiums by encouraging employers to pay 90% of the premium with money that doesn’t even show up on the pay stop, to ‘EOB’s that show prices inflated by over 1,000%, making patients think their insurer is really helping out.

If patients paid for non-catastrophic health care the same way they paid for non-catastrophic home maintenance and repair (credit card, financing with providers, or even paying themselves then filing an insurance claim), prices would be held down nicely.

Of course that wouldn’t address the concept that ‘ordering a diagnostic test doesn’t fix symptoms’, which I agree with, but at least it would be the patient’s choice, because it would be THEIR money.

While I agree that care needs to be used in choosing if/ when/ what for diagnostic work up for back pain, I think that care also needs to be used on who/ what kind of physician this article is targeting. This may pertain to a PCP, but as a physiatrist with spine clinics, my typical patient population has chronic low back pain and am probably the 10th physician they have seen for the problem- thus I have a very different group of people. Just the other day, I had a patient with benign looking spine pain, and sure enough, diagnostic imaging showed an aggressive tumor- and this is not an isolated occurrence in my practice. So before broad brush strokes are used for ‘guidelines’, there needs to be very specific explanation of the cohort. Otherwise, we end up missing diagnoses that render harm to a patient.

An aggressive tumor should have some characteristics suggesting bone pain vs non specific back pain and cheaper and faster CT scan would have picked up that condition. Probably an LS spine series would have. There isn’t much likely hood of treatment being of value so you are still going to provide palliative care in your practice. Back pain is a mysterious and pain in the butt problem for GP/PCP’s. They love to turf them and get them out of the practice. If you really liked at your data of actual clinically relevant results, are you finding more than the PCP’S. One case study isn’t proof. A really good clinician should be done fewer studies.

Unfortunately, certain patients should not wait six weeks, nor the six years I had to wait for my back pain. When I finally had the MRI, I was walking with a walker, had a neurogenic bladder, and the MRI demonstrated severe spinal stenosis L3-5 and a Grade IV Spondylolisthesis, plus severe spinal stenosis C5-7. What I noticed is that physicians get their imaging studies and back surgeries ASAP, while lesser beings of the universe have to beg to get imaging studies to prove they have a severe back/neck problem. My legs were weak, and I had no Achilles reflex. I worked until the day before my back surgery. My EMG and NCS were pain free to both my UE and LE. This article is tripe.

I am wondering why Osteopathy is not discussed as a viable option for back pain?… there are more and more community clinics…?

This is what happens when heath policy is driven by greed, ignorance and industry insiders. At the same time MRI’s in other countries cost less than 70$. I heard this false narrative repeated by a congressman, and industry paid politician. No one stopped to ask hwo this kindof information could be used to deny care to patients or to make things even worse. Most of the tie back pain resolves itself, but like everything else in healthcare, we expect a physician to know the difference. Due to this false narrative, people who already have MRIs are not having them applied to their health documentation, even when these are post surgical.

In the US the false narratives in healthcare that actually get repeated by politicians are the ones that help the industry make money and avoid liability. No actual research was done on how many times a patients was denied an MRI only to find out they had a serious problem. Our healthcare system is easily described as a criminal enterprise, necessitating real systemic change. The insurance industry funds a lot of the “research” and academia is no longer scientific or independent.

Mass media has already, at the request of industry run informative edumercials and content marketing on this topic. The real message is that lower income, minority or female, injured people with “back pain” will be denied treatment out of concern, that MRIs are “dangerous.” People with severe injuries, nerve damage and worse, will be told to wait it out. Of course for low income people every health appointment is like the first time, so a injury reported 6 months ago, that gets worse, will be treated again like it just occurred.

There is no doubt that this false narrative will be used to make things worse. The US is already rationing healthcare, and this is a clear example. A spinal injury will lead to loss of employment, lost of insurance, and increased depression, and suicidal ideation, and going un diagnosed. There are plenty of homeless people who were injured in the Gig Economy, whose attempt to get healthcare, left them to lose everything, their homes, their insurance and their dignity. This is most likely what is behind this move to make MRI’s appear dangerous.

This is a fact America, where a paid corporate false narrative becomes health policy, and lies are considered good for business.

I started getting low back pain in my 20s that would immobilize me. Initially I had Cigna, and all they wanted to do was give me muscle relaxants. So first open enrollment I switched to PPO insurance. I went to an orthopedic surgeon who ran some x-rays and derermined i was missing the little bones in my vertebrae that keep them aligned. He said he could make big money to fuse the vertebrae, but it was risky, long term recovery, and it could make me worse. He recommended physical therapy instead and it worked miracles. He said never allow a chiropractor to touch my low back.

Nevertheless, over the years, the vertebrae moved, caused the disk to rupture, disintgrate, and now I’m bone on bone with 25 percent contact. Went through periods of intense pain, but PT and avoiding aggravating activity helped. I have gotten x-rays, CTs, and MRIs over the years that documented the progression. I’m lucky because it happened slowly over time and the nerve channel slowely adjusted.

For my neck, i wasn’t so lucky. I had one surgery, but the rest of the neck vertebrae alignment are slowly and progressively getting worse. So again, PT and avoiding aggravating activity is what keeps me going, although I did have to quit work, as the worst thing for the spine is sitting and working on a computer.

These are some of the many reasons why all non-allopathic medical modalities should be explored first. Homeopathy, Kinesiology, Acupuncture, Remedial Massage, Herbal medicine, Essential oils, the list is long, can all help with the experience of pain and the causes of pain without expensive and interventionist Allopathic treatments.

Given how modern medicine, Allopathy, is crippling economies and is now the third biggest killer, most of it from prescribed medication, it should be all medical professionals who are demanding Integrative Medicine in order to offer patients safer, non-toxic, less expensive treatments.

I have had back pain for 25 years and there is nothing that can solve the problem. I have herniated discs at the L4 L5 and L6 (extra lumbar) and have had MRIs over the years various other scans but the only test that showed the damage was a discogram. Saw the best back spinal specialists in the country with the same diagnosis – very bad back and no one can fix it and not to let anyone tell me otherwise. Over the years with limiting lifting or doing it right and exercis on a regular basis the pain is controlled. Even found that kick boxing (non-competitive just movement) and golf help a lot. Why these sports and there are others teach proper body movement and posture. When I do have a flare up resting keeping hydrated and slow exercise solves the problem over a couple hours. The MRIs when I had them did not show the problem neither did CT or other scans. They were a waste as was PT. I did try chirpractic and that did not help since I had physical damage as well as soft tissue. Chiro tryed manipulating the soft tissue but could not relieve the pain. And the scans I had did not accurately show the soft tissue damage. Recently had another MRI for another health issue and as a side note when they read the scans they looked at what they could see in the back and reported that nothing had changed. What I found is that the MRIs, CT and other scans were a waste of time and money and the discogram was the only test that showed the damage. What reduces the pain, not surgery, but exercise, proper posture, hydration and being active.

I have cauda equina syndrome resulting from an old lifting injury form the 80’s but it finally gave out June of 2019 while running. I’ve suffered with pain in my hips and lower back for decades while racing bikes thinking everyone was feeling the same thing. Finally while running the disc at L1-L2 called it quits, and I lost most function of all bowel and bladder with major weakness in my legs, after 1 month there was complete lost bowel/ bladder function with unimaginable pain in the lower half of my body so I finally went the ER. The MRI showed a problem at the L1-L2 vertebra but the neurologist said it didn’t explain my symptoms. I ended up seeing a neurosurgeon who operated at that site and found that the MRI and the actual damage done at L1-L2 were different. The MRI wasn’t accurate and I’ve dealt with not being able to use a bathroom like normal people for decades until till the surgery. I’m still recovering but there has been a vast reduction in pain and some restoration bowel and bladder function. No neurologist was willing to make the call because it wasn’t a textbook example, until the neurosurgeon helped me. I think that too often doctors will ignore the symptoms, and depend too much on test results to make a call. I’ve raced bikes for over two decades hunched over in a aero-position two to eight hours a day everyday of the year including holidays, and doing Olympic lifting during off season also two to eight hours a day. Laying down with a flat back was never remotely a normal position for my back. My point is I am not a textbook patient but that is how I have been treated.

This was clearly written by a chiropractor.

What makes you think that, I didn’t pick up that feeling. The article was advocating no treatment and chiropractors are into treatment. Once we get past physical injuries, physical deterioration, the worlds your oyster as it can be referred pain from hip or knee or ankle via the sciatic nerve or it could be an old injury being targetted by a medication you are taking or it could be the rest of an allergic reaction to the polyurethane foam fumes from your mattress that are released by your body heat. Now you may say crap but if you’ve had a physical injury to say the L4, L5 disks as I did the result of the body deciding to protect itself from intense pain caused by a bone chip in the ankle impacting the sciatic nerve. Once the bone chip was removed and physio on the back it improved and then I developed intense back pain when in bed and crippling pain trying to stand but by 10:30 am that pain vanished. Accompanying my wife to the allergy specialist she was discussing her back pain and the progress she had made changing to a wool pillow and then a wool mattress protector he suggested we get a wool mattress. Hey what the heck it’s only our money I thought so we ordered one thinking yeah this will be a waste, woke up the first morning after sleeping on it and hey no pain for either of us. Having progressed further down this pain allergic reaction pathway this has to be considered as we seek improved physical health.

Yes you are so correct. Every time I have been sent to physical therapy for my back I got worse. No one wants to listen to the patient. They act as if we are stupid but we can see right through it all. I don’t know what they are up to but it is no good for the people of the United States. Doesn’t look good at all. The insurance companies aren’t making the amount of money they want apparently. They claim they are spending too much money on testing such as MRIs. This is one of the best diagnostics tools we have with less exposure to radiation. I hope they haven’t been misleading the public about these test too. While these companies are getting rich. This is such a bad idea. Taking good quality health away from people here is a crying shame and a disgrace to the human race. In humane.

I can hardly believe what I just read!

I’ve been requesting an MRI of my lumbo-sacral back since 2015. Fast forward four years with the entrance of numbness and weakness in both legs. MRI granted. The bulging discs, bone spurs, thickened ligaments and severe stenosis of L3. No options other than surgery at this point. This is ridiculous!

Better diagnostics may be needed but to withhold access to technology that can lead to early identification and intervention of serious, life altering disability is nothing short of criminal. Should be no different than a mammogram.

The article is NOT anti-imaging. It is only suggesting that six weeks be given first to see if the pain can be sorted out on its own, or with corrective therapies. Jumping right into tests because that’s what doctors want to sell you plays to people’s own hypochondriatic impulses. I’ve had horrible back issues–upper back affecting balance and even ability to walk, heart palpitations, anxiety attacks, you name it. A general practitioner would have ordered up no doubt countless “tests” to no avail. Instead I go periodically to an upper cervical specialist for a minimal adjustment and know how to properly straighten my back on the floor, which should be done daily. Problem solved! Neurologist, I don’t need no stinking neurologist. And no irregular heartbeat drugs either. (Sorry, my antipathy toward the health care industry in general is showing.)

Back straitening exercise on the floor?? I would love to try what you do! What do you do?

What a bunch of garbage. MRI’s show soft tissue damage such as herniated disk which if not repaired can lead to permanent nerve damage. Patients deserve the best available care, too bad about insurance companies profits.

As an MRI/CT/XR technologist, I both agree and disagree with this article. Where there are cases that physical therapy will help, there are cases that physical therapy will hurt a stress fracture in the lower spine, Or a ruptured disc. Some insurances will not allow imaging until PT is performed. Other insurance (Medicare for ex.) do not require any sort of precertification. Healthcare has turned into a business instead of an institution for the betterment of patients. In short, there are many circumstances that are not mentioned in this article.

As a person who has suffered from low back pain for over 30 years – and have had doctors refuse to do xrays or Mark’s – I have done chiropractic care and acupuncture for relief from a Chinese medicine doctor and got more information about the condition of my spine than my own doctor despite the fact that the crop (blood test that measures inflammation) being dangerously high. Until I had a MRI in June of this past year (not the first) but he first one that finally enumerated the congenital malformation of my lower spine that DOES impact my overall health as well as the disc malformations and the severity of the degeneration of my lower spine. It is hard to properly treat what you can’t see and we all experience pain differently.

You are right a chiropractor ordered too many test while i had concussion symtoms. It may have messed up a slip and fall case.

MRI is waste in the absence of Red flags.

90% of pain is due to a prolapsed disc. Loss of Lumbar Lordosis on a plain X Ray indicates muscle spasm due to disc. Most painful sciatica patients do not have a prolapse on the MRI. They show a Hyperintense blister lesion. These don’t need surgery. The biggest prolapsed disc’s on the MRI have minimum pain & will get resolved over time , provided no new prolapse occurs due to continued spinal flexion.

Now treat the cause of a slipped disc & not its symptoms. Teach prevention of spinal flexion in the day to day life. Teach passive hyperextension to relieve the symptoms along with NASAIDs.

Even if surgery is done , further prolapse can occur unless the back is looked after from flexion.

Because doctors don’t want the patients to get mad at them and sue them.

Malpractice concerns drive a huge amount of unnecessary testing. Because trial lawyers are big supporters of the left wing, the liberal media, like here, excuses or overlooks them.

Until this issue is honestly addressed, the problem will continue

I had the same problem for almost a year, I used to see a chiropractor but finally doctor sent me to physical therapy and had a few appointments for traction on low back and was so grateful to be rid of that horrible pain!! Yes, I have stomach problems from ibuprofen now!

I also had horrible pain in spine between shoulders but found out my neck injury was causing it after having traction on my neck a couple time with a little therapy. Grateful to find something to work!

What the HELL are patients supposed to do SUFFER NIGHT AND DAY WITH NO DRUGS NOW THANKS TO THE SO CALLED OPIOID CRISIS. WHAT DO WE DO@! WHAT!! MY PT DIDN’T WORK! TJE POOL DIDN’T WORK! THE MUSCLE RELAXANT DIDN’T WORK!! I HAVE A FOOT THAT SHOOT PAIN FROM MY BUTT TO MY FOOT LIKE BURNING HELL AND I don’t sleep!! All I want to do now is DIE!! I HURT SO Badly now!! No one wants to do a damn thing! Talk it out and take Tylenol and Aleve I’ve done so much that I have killed my kidneys and killed my stomach. Now what!! I am bleeding from my rectum!! My blood pressure is Sky high and I am on High blood pressure medications and my numbers are sky high and NO ONE CARES!!

Get a better Physical Therapist.

This is incorrect information. People and doctors need any information they can get to treat the patient. No such thing as too much info when it comes to your health. This article sounds like propagandat from the insurance companies so they can have yet another reason to take a person’s money and not have to cover their medical expenses. That way they can make even bigger profits than they do now.

Freda,

Make an appt. With Dr. AVNEESH Chhabra at UTSW in Dallas TX

He is a diagnostic radiologist. UTSW has a 3.0T MRI with high resolution and you will see Dr. Chhabra in person to review your imaging. He patented a specific MRI protocol. Lumbar- sacral Plexus imaging needs a HIGHLY skilled expert reading.

In the past with other doctors, you may have gotten a reading radiologist who is not making appropriate clinical indications with respect to your symptoms. I encourage you to keep seeking answers.

I care and lots of people care because we are going through the same thing. I have sacrolitis and sacral iliac joint inflammation and the steroid injection in my joints help me but do not act long. This pain has gotten worse every year since 2012. I am wearing a SI joint belt from sacrotech and that helps some. They are supposed to be getting a MRI of my hips and lumbar spine. And possibly have ifuse surgery. I’m not sure he’ll want to do surgery since I also MS and I think my gait is what is contributing to the hip pain. Heat and or ice helps me. Praying ? for you to get some relief.

I hear ya Freda. I’ve had cortisone shots in my spine; the machine that stretches the spine; acupuncture. NOW I’m laying here having had a knee revision 2 weeks ago — they took out my old knee replacement and put in a new one. He thinks that with cortisone shots in my groin for my hip (wtf?) and the new knee I’ll be able to walk again. So I got 9 days worth of Percocet. I’m doing bone-grinding PT now. I will NEVER get another scrip for Percocet. They refuse. I couldn’t do the PT without my supply of Gabapentin that I have for my back. Regular people are suffering everywhere because doctors now refuse to give them an opiod. People are committing SUICIDE because of pain. So, decent truly suffering people have to pay the price because of lowlife drug addicts. This is a GOVERNMENT decision so call every politician in your area to get this opiod law reversed. I pray you get well.

I have lower back problem aperdual helps me a lot don’t have any problems after that

Freda Lovell. I think you misunderstand the intention of the article. Someone with new onset of pain does not need an MRI because it does not explain the cause of their symptoms any better than a clinical exam. In your case if you have ongoing pain, have failed at conservative treatment (you say “PT” didn’t work, that is what failing at conservative care means) then you are a candidate for further evaluation and treatment. If you have leg pain, then you are certainly a candidate for an MRI if you have ongoing pain. Sometimes things do hurt more before they get better but this is only hurting more for a few days so if what you are describing is something going on for weeks or months, go get some help. Just to review the article, if people get MRIs early on, there are way too many “false positives” and people get treated for things that show up on the MRI and not for what is actually wrong with them. That is what the article is saying. It is not saying “never do anything to people.” In your case, maybe try another PT (I would suggest trying 3 or 4 and trying to find someone more adept at helping you navigate through this problem). Or another doctor. Certainly if you have rectal bleeding, you need to discuss with an MD ASAP. There are plenty of caring practitioners, I hope you can find someone. I deal with frustrated patients all day long, so I get that part of it.

I had my 3rd major back injury about 6 years ago, poor lifting form. I’ve had a Tens unit, spinal realignment, etc. A pain management doc said I have 3 deteriorating vertebrae and 3 protruding discs. I’ve also been diagnosed with arthritis Iin my neck, lumbar, and knees, Neck and lumbar are scheduled for cortisone injections, which I have zero faith in. Knees will have to wait as I’m currently going through physical therapy after a gun shot wound through the left knee.

It’s fine and understandable

Remove . Scrapp CPA for medical professional and things should improve .

This sounds like it was written by someone that works for the insurance co.panies.

It actually isn’t written by insurance companies. This is research that has been going on for almost 30 years. Treating based on MRIs has created more problems for people because the MRI does not always (and actually rarely) shows the problem. Many articles on pain discuss “85 to 95% of back pain is non-specific back pain.” the “non-specific” means “not explained by diagnostic testing.” This didn’t come from insurance companies at all. If you read peoples comments, they are often mentioning “degenerative discs” and herniated discs” and how they aren’t any better. The reason they aren’t any better is maybe (and the point of this article) that isn’t the problem in most (but not all) cases. 2/3rd of people 40 years of age with no history of back pain have considerable abnormalities on their lumbar MRI.

Interesting that this article should come up now while I am in the midst of reading the book “Healing Back Pain” by John Sarno. This article echoes a lot of his theory about the back pain epidemic. A good read for anyone who deals with this problem in life, but only if you are open to the thinking that current conventional treatment may not be really getting to the root of the problem.

Berry informative

THANKS FOR THE ARTICLE IM A 57 YEAR MALE AND HAVE HAD BACK AND SPINE ISSUES MY WHOLE LIFE IVE BEEN FUSED FROM TOP TO BOTTOM I RECENTLY MOVED FROM WISCONSIN TO FLORIDA AND MY BACK ISSUES HAVE RESURFACED IVE BEEN TRYING TO GET AN MRI OF MY LOWER BACK BEEN WAITING 2 MONTHS FINALLY HAVING TO SELF PAY BEEN IN CONSTANT PAIN FOR 3 MONTHS I DO UNDERSTAND THE IMAGING CONCERNS BUT AS ALIFE LONG BACK/SPINE SUFFERER I AM FRUSTRATED WITH MY INSURANCE FLORIDA BLUE WHICH I SELF PAY $900 / MONTH WHEN A PERSON IS IN CONSTANT PAIN THEY JUST WANT RELIEF MRI/CT SCAN GO THROUGH THE PROCESS BUT I KNOW MY BODY BETTER THAN AN INSURANCE COMPANY PLEASE DONT DELAY APPROVALS RESPECTFULLY SUBMITTED

so if they’re not requesting for people to have MRIs or ct for the pain in your lower back what are they requesting for patients to receive what kind of therapy besides physical therapy what kind of testing can they have besides just an MRI or a cat-scan and what kind of relief are they going to get from you cuz I am a patient of spinal degeneration for 23 years I had eight back surgery with numerous MRI and cat Scan spinal injections three neck surgeries my spine needs to be reconstructed so tell me what should a patient that is that bad. For relief of major back pain my lower legs are striking piercing pain up my spine to my neck my hands are numb my legs were numb what do you suggest a patient like that should gets then

The Author of this study has many facts simply wrong.

And the protocol the author suggests put patients in danger and fuels insurance carrier rhetoric.

Disc herniations do not occur much in the asymptomatic population. The literature is clear on this.

X-rays are not cumulative and are very safe and cheap. In fact, not ONE case has ever been documented of a person being injured from plain xrays. Not one. EVER.

MRI should be immediately ordered when there is; radiation of pain into extremities, positive orthopedic tests for space occupying lesions, sensory and/or motor deficits present in extremities.

MRI should be only delayed in ordering if there is no radicular symptoms. Only then should conservative care be initiated after taking plain xrays.

Patients can be INJURED by some types of conservative care in some cases and therefore if the treatment is anything other than pills…imaging is warranted and important.

An accurate diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plan are dependent upon spinal imagining. To say otherwise is simply wrong and dangerous.

If I go to see my Dr. for any kind of pain that has been with me for years I would rather have a MRI or X-ray so that if there was something on the scan that does not look right and may be causing the pain it can be found immediately and dealt with appropriately at that time instead of dragging it on for many more months or years.

You must have gotten your facts from statisticians instead of real folks facing pain. Never met a person who had back pain for a few weeks, then got an MRI; more like months or years. I had a lumbar fusion 5 years ago. I’ve had pain since the middle of 2017. Mega ibuprophen and gabapentin, exercise have done little. New MRI says arthritis is continuing to take over. MRI? Why? Nothing wrong with me!

Hi. I find this article interesting, but I feel it leaves out cases such as mine. I suffered for over a decade with undetected Ankylosing Spondylitis. In that time, the disorder progressed to a fusion of L5 and the sacrum, as well as degeneration of some mid back vertebrae and massive inflammation of my sacroiliac joints on both sides. I had been to multiple doctors and had been told various stories about my thyroid, my weight, depression leading to chronic pain, etc….. All with no imaging or intervention of any kind other than massive doses of NSAIDs and some eye rolling. Without a family history of autoimmune arthritis or undeniable symptoms of lupus or something it is very difficult to get anyone to take you seriously, especially if you are not stick thin. Finally I found a doctor who would listen and order an X-ray. By the time we were finally looking at the possible underlying cause of my pain, the disease had already progressed significantly. My point is, chronic pain in your lower back isn’t always just whining and begging for unnecessary procedures or pain killers. There are other ways to discuss the overuse of medical care that does not minimize patients suffering, or set up an adversarial relationship between doctors and patients.

I agree with this 100% I’m in the same boat with bertolotti’s syndrome. By the time imaging was done I now have 3 degenerated discs and stenosis, I’m only 34. The surgeon said if this was caught earlier there might be more options but it’s now rather likely I’ll have to get a fusion sometime in the near future.

I’ve heard this kind of advice put forward in so many different venues by many respectable people so I guess there must be something to it, but I can’t help feeling it doesn’t add up. X-rays have a radiation concern but MRI’s are totally safe. It seems to me that more knowledge is always better, and if knowledge is causing bad decision making it’s the decision making that needs to be reevaluated not the acquisition of knowledge. I don’t understand who this advice is meant to protect, aside from insurance company’s pockets. Meanwhile people like you and me are left with bad surgical options for managing degenerative diseases that could have been prevented.

Absolutely right. The doctors should encourage the people to have appropriate physical exercises to improve the muscles.

my left shoulder down to my elbow has been hurting all the time 24-7 I fell on it I lost my balance in my house I told my doctor about it but he didn’t do anything it’s been getting worse and worse I can’t understand the pain anymore supposed to have a MRI this coming Thursday give me a call if you want to talk to me 574 520 seven seven 04 my name is Faith thank you

Faith, I fell on my right shoulder about ten years ago. The pain was very bad. I went to the ER the next day due to the pain continuing. I was given a sling and a prescription for some painkillers. The pain only continued to worsen so I went to my regular doctor. He referred me to a neurosurgeon who ordered an MRI. I had completely torn my rotator cuff in that shoulder. I had surgery to repair it. Afterward, I went through physical therapy to strengthen the muscles around the shoulder and also to increase the range of motion. I will tell you that I had a painful recovery, but did recover and to this day, unless I overexert the shoulder, such as lifting something heavy overheard, I am doing fine. My latest problem is that I fell last year on the other shoulder,and an MRI showed I had torn this one too. I could not have surgery at that time because I was already scheduled for back surgery, which was more necessary at the time. I am now preparing for surgery on that surgery. Hope this information is of some help.

I want to ask you a question I have been having it in my shoulder down to my elbow everyday 24/7 I’ve got to have an MRI on this coming Thursday what do you think about that what do you think it might be because it hurts like I said 24/7 I heard it back in October of last year I told my doctor about it and didn’t do anything about it it’s been getting worse and worse it hurts all the time

Very true information. Apart from the financial incentives for the health workers, patient’s psychology plays a significant role in getting various tests through physician’s advice. Patient psychology across the globe says that if a physician doesn’t advice various tests for diagnosis, he is not a worth physician. So, it’s to satisfy this patient psychology, most of the physicians write for tests.

The problem articles like this fail to mention is that for insurance reasons doctors don’t tend to differentiate patients who have already tried weeks or months of conservative treatment with hypochondriacs who show up in the office after a week of mild discomfort.

As a patient it’s infuriating to show up at a doctors office after months of struggling with disabling & life deranging levels of pain (knowing that back pain normally passes after a few weeks with nsaids and physical therapy) only to be told that the 6 week clock only starts after the doctor has seen you.

How about MRI studies for neuropathy? I have been told I have a(n) l-4, l-5 impingement. That could be causing neuropathy.

What if someone is dx with DDD age 18 ?

Unfortunately, my doctors followed the protocol exactly and instead of imaging, I was given prescriptions for physical therapy year after year for 15 years. Then, in 2014, when I was taken to the emergency room unable to walk, an MRI of my l owner back was taken. My spinal cord was fused to bone at L5. I was diagnosed with reactive psoriatic arthritis and had to have a three level spinal fusion. Because it took so long to diagnose me, My thoracic spine has degenerated and will require surgery when I decide I can’t stand the pain anymore. Protocols are well and good but but the first thing you learn in law school is there are exceptions to every rule. Rigid adherence to a protocol demonstrates a failure of professional judgment. An MRI when I first started experiencing chronic pain would have shown immediately that I had some form of psoriatic arthritis. By the time I was diagnosed, nearly every joint in my body was affected as well as my lungs, small intestine, and large intestine. Doctors need to know when to exercise judgment.

I totally disagree with this, my physician did not want to do an MRI of my spine months after a serious car accident. But I suffered continuous immense pain. I was then sent to physical therapy which made my pain much worse and nearly paralyzed me and put me on permanent disability. When imaging was finally ordered I had three moderate herniated discs as well as a fracture in my neck that if it had shifted in the slightest I was told that I would have been paralyzed for life. Plate,screws and donor bone and my neck pain was very much manageable. As for the T7 and L4-5 herniation I am on disability due to not being properly diagnosed before physical therapy was ordered and am disabled becsuse thry cant do surgery on T7. Just how many patients have been permanently disabled due to phyicsl therapy not knowing what areas are damaged.

Same here. I had a neuro physical therapist post stroke who actually fractured a cervical plate screw in my neck doing his evaluation. I only found that out from imaging. It is a fairly rare hardware failure especially 12 years post surgery Then they discharged me from OT and PT because I was having so much pain, BP was high, and I was considered a liability, smh… And they also refered me to Psych. It took months to figure out and now with the opiod restrictions and no NSAIDs due to Eliquis, I have been told I will be in moderate to severe pain the rest of my life. Get used to it.

Also wish to point out my neice just finished her residency for primary care. She has been taught that Doctor’s have no obligation to relieve pain. Nice out….smh