In a Study of Human Remains, Lessons in Science (and Cultural Sensitivity)

The subject matter was obscure, but the findings were provocative: A genomic analysis of a mysterious skeleton found in Chile’s Atacama Desert revealed that the remains weren’t those of an extraterrestrial, as was wildly speculated, but a human fetus with an unusual bone disorder. The study, published in the journal Genome Research in March by Garry Nolan of the Baxter Laboratory for Stem Cell Biology at Stanford University and his colleagues, was intended to put to rest speculation that the mummified remains might prove the existence of alien life — but the controversy over the remains did not end there.

Instead, the paper sparked outrage within the academic community, and managed to raise broad questions about scientific ethics and cultural sensitivity. Among other charges, critics have questioned whether the researchers took proper precautions to ensure the remains — which belonged to a member of a local indigenous community — were collected and exported legally. Many stakeholders have accused the team of violating Chilean laws, however unwittingly.

“What went wrong here?” asked Cristina Dorador, an associate professor at the University of Antofagasta in Chile. “Everything,” she declared, “from the beginning.”

Concerns over the proper handling of research specimens by international teams of scientists are not new, especially for high-profile papers. In 2015, for example, a group of paleontologists published findings on a purported four-legged snake fossil from Brazil that may have been illegally excavated and transported to a German museum. But the Chilean study drew harsher criticisms because the remains were human, and while many scientists acknowledge conducting research on people should require additional ethical considerations, studies on human remains don’t fall under the same laws as human subjects who are alive.

Regardless, many experts say that approaching such work ethically requires reaching out to and working with related persons or communities — something that, in this case, wasn’t done. The underlying research premise — determining whether the remains were human or alien — was also part of the problem, detractors said, because it weakened the scientific merit of the paper. To many critics, the appearance of Stanford’s Nolan in a 2013 “documentary” about unidentified flying objects suggested that notoriety was the goal rather than scholarship.

(Some critics also argue that all other problems aside, the Atacama researchers made a glaring error: According to forensic experts, including ones that examined the fetus prior to the Genome Research study, the Atacama mummy didn’t have a bone disorder at all.)

An email to Sanchita Bhattacharya, the first author on the Atacama paper and a bioinformaticist at the University of California, San Francisco, brought a response from Nolan instead. Writing on behalf of the paper’s 15 co-authors, Nolan said that his team’s responses to the various criticisms were already public — including a formal response on the journal’s website. “We respectfully refer you to those prior materials,” Nolan said. “We will not provide any further interviews, written or oral.”

The editors of Genome Research also declined a request for an interview — though executive editor Hillary Sussman responded via email. “We have just published a statement regarding Bhattacharya et al. (2018),” she wrote. “We remain interested in community discussion towards establishing appropriate journal policies and author guidelines necessary for the publication of studies involving historical and ancient DNA samples, but as we are in the organizational phase we have nothing more to add in an interview at this time.”

The reluctance of both the authors and the journal to comment further on the incident hints at the very knotty cultural, political, and ethical questions that attend human-specimen study — particularly in an era of increased sensitivity to the rich world’s habit of trampling on national and indigenous rights in pursuit of archaeological scholarship. At the very least, many experts say the Atacama paper offers some potent and useful lessons in how not to handle such research — lessons that are especially important now, as new technologies that allow for genetic profiling of older, smaller, and more degraded specimens create new ethical quandaries.

The origins of the study date back to 2003, when a man named Oscar Muñoz discovered the tiny set of remains wrapped in cloth and tied with a violet ribbon buried near a church in the abandoned town of La Noria in Chile’s Atacama Desert. The mummy’s elongated head and other features were striking enough that local tabloids soon reported Muñoz had discovered an extraterrestrial. He sold the remains to a local businessman for 30,000 Chilean pesos (a little over $40). It’s unclear how many times they changed hands, but “Ata,” as she came to be known rose to prominence in ufology circles for her striking appearance. Eventually, she was bought by Ramón Navia-Osorio, a wealthy Spanish entrepreneur and head of the Spanish Institute for Exobiological Investigation and Study. The remains are still in his collection of purported alien artifacts in Spain.

In an article published on the website of the To The Stars Academy of Arts & Science, a Los Angeles startup devoted to funding research into “exotic science and technologies,” Nolan — an immunologist by trade — explained how he came to study these remains. “I had heard about the Atacama specimen … from a friend with an interest in UFOs,” he wrote. “I immediately thought, ‘Well — if it has DNA I can determine if it’s human.’” So, he began enlisting colleagues to aid in what would become a five-year study of the remains, culminating in the Genome Research paper.

Much of the backlash centers around the likelihood that the remains were illegally collected and exported, violating Chile’s cultural and biological patrimony laws. Chilean authorities have launched an investigation into the matter. Certainly, the story of the discovery by Muñoz and eventual transport to Spain — if accurate — suggests behavior in violation of both Chilean law and international agreements regarding looting. Chilean law clearly states that permission from the Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales (National Monuments Council) is required prior to any excavation or export of objects or remains with artistic, historical, or scientific importance. If the law had been followed, the specimen would have had paperwork to say as much.

But the researchers’ published statement suggests they neither asked for nor received any such documentation. “We had no involvement or knowledge of how the skeleton was originally obtained nor how it was sold or exported to Spain,” Atul Butte, a co-author on the paper, told The New York Times. He added that the team had “no reason” to suspect unlawfulness.

Archaeologists, anthropologists, and paleontologists generally want to know from where a specimen was recovered and the chain of custody by which it traveled to the researchers.

The Society for American Archaeology, for example, says the group’s journals do not publish new findings from specimens with unknown histories. The society also specifically notes that the buying and selling of archaeological specimens “is contributing to the destruction of the archaeological record on the American continents and around the world.” Researchers in fields such as paleontology and anthropology have similar concerns.

“You cannot just say ‘I don’t know,’” said Nicolás Montalva, an anthropologist at the University of Tarapacá in Chile. “You have to do the queries and know where the samples are coming from.” Chilean law also requires that foreign researchers collaborate with Chilean scientists to obtain permission to excavate or export archaeological, anthropological or paleontological specimens excavated from Chile. Said Siân Halcrow, a bioarchaeologist with the University of Otago in New Zealand who has worked in Chile before: “You should have had to have gotten some kind of permission or sign-off.”

In recent years, nations outside North America and Europe have also increasingly stood up to claim the right to be a part of studies that examine parts of their biological and cultural heritage. Chile’s laws protecting items with artistic, historical, or scientific importance are a part of a growing movement to prevent what’s been called “biopiracy” or “parachute research” — studies where U.S. and European scientists drop in, grab a sample, then conduct the actual analyses elsewhere, preventing local scientists and communities from benefiting directly from their own resources.

One of the reasons many seem to have such strong reactions to the Atacama case is that the remains are not only human, but they also are of an indigenous Chilean, which some critics say led to the disrespectful way in which the data in the paper was presented and the sensational angle of the press coverage.

Nolan and his colleagues emphasized in their published statement and in interviews that they were initially unsure if the remains were human. None of the data they collected and analyzed provided “identifiable information about a living individual, as defined by federal regulations, and does not qualify as human subjects research” they pointed out in a statement.

That assertion is correct under federal law in the U.S., which doesn’t regulate research on human beings once a person has died, said Pilar Ossorio, a professor of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The only major exception from a legal perspective is for remains that come from native communities, which fall under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

In a 2013 documentary made by Sirius Disclosure — a group seeking “development of a peaceful relationship with Extraterrestrial Intelligence” — Nolan said that his preliminary research suggested “with extremely high confidence that the mother was an indigenous Indian from the Chilean area.”

There is no such provision in U.S. law for non-U.S. native communities, meaning the remains fall in a somewhat nebulous, ungoverned area of research. “When you’re studying skeletal remains or human remains from the past, you very well might be impacting living groups, living communities today,” explained Chip Colwell, a senior curator of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

Even without identifying data that would pinpoint close relatives, local communities connected to the skeleton could be harmed. The presence of the genomic sequence could have unforeseen legal impacts, such as affecting claims for repatriation or treaty negotiations, as genetic evidence is increasingly involved in legal disputes. The communities may also feel that the information regarding genetic disease susceptibility is stigmatizing, and insurance companies could even use medical information inferred from the research against related communities.

Colwell believes scientists “have ethical obligations to at least take into consideration the rights and concerns of those living communities.” He said that means asking tough questions up front. “We can’t just make assumptions that just because someone possesses it that they have a right to it,” he said, “or that then gives you the right to study it.”

That means researchers need to be prepared to pause or potentially terminate a study if new information is obtained, said Joe Watkins, president-elect of The Society for American Archaeology. “If they did not know that they were human remains at first, the minute that they determined that they were human remains, they should have stopped the research and then asked even more questions.”

In the course of the investigation, Nolan and his colleagues not only realized the remains were human, the team also estimated that they were only around 40 years old. That means that Ata’s parents or other close relatives could be very much alive. At that point, prior to publication, Colwell said he would have made “a very concerted effort to reach out to at least potential claimants or potential relatives to get their input on the appropriateness of the study as well as any publications.”

“I think it’s really important that we acknowledge that when we do research on human remains we need to do a different kind of science and have a different kind of ethical engagement,” he said. Ann Kakaliouras, an associate professor of anthropology at Whittier College in Southern California, agreed with that assessment.

“There were many more collaborative ways to do this than just, ‘Sure, take the DNA and let’s find out,’” she said. Balancing the interests of the remains’ owner, Chilean authorities, scientists, and potentially related people or communities would have been admittedly “sticky,” she said, but she feels that the way the science ended up being conducted was simply unethical.

The journal, too, many critics have argued, failed to ensure that the science it published was ethically conducted. As its title implies, Genome Research is a genetics journal. Experts said that could explain why neither the editors nor the peer reviewers flagged the ethical issues with the study. “Geneticists are not sensitized to the same kinds of issues that archaeologists are,” Kakaliouras said. Had the paper been brought to an archaeological journal, she thinks things would have played out differently.

The real question, though, is what Genome Research should do now.

“They should retract the paper,” said Dorador, of the University of Antofagasta in Chile, “and in the future, they have to include this subject — ethics — in their instructions for authors.” (The editors of Genome Research have stated that they stand by their peer review process and have no plans to retract the study).

Others, like Montalva of the University of Tarapacá in Chile, don’t really see the point of pulling the paper now. “That might be a step, a symbolic gesture. But whatever damage there is, it’s already done.” He added that the journal authors aren’t entirely responsible for the story going viral. “I think the press and the scientific public also have some responsibility.”

Dorador pointed out in an article in Etilmercurio, a grassroots Chilean science publication, that Ata had a family who loved her enough to wrap her carefully before laying her to rest, and a mother who could very well be alive and watching the media storm surrounding her dead daughter unfold. Dorador says she intentionally didn’t include any photographs of the remains in her piece, and she noted that other Chilean outlets also refrained. She and other experts also condemned the use of the word “humanoid” as a descriptor, which implies the fetus is somehow non-human — a word journalists may have gotten from the paper itself, as the authors use it in the abstract and the opening paragraph.

That’s one of several reasons why Kakaliouras of Whittier College thinks coverage of the findings is ultimately the fault of scientists. “We’re so ready to sell the public the best, most unique, most fantastic archaeological finds, and then we’re surprised when that’s what the public is most interested in,” she said. “I just can’t put this on journalists.”

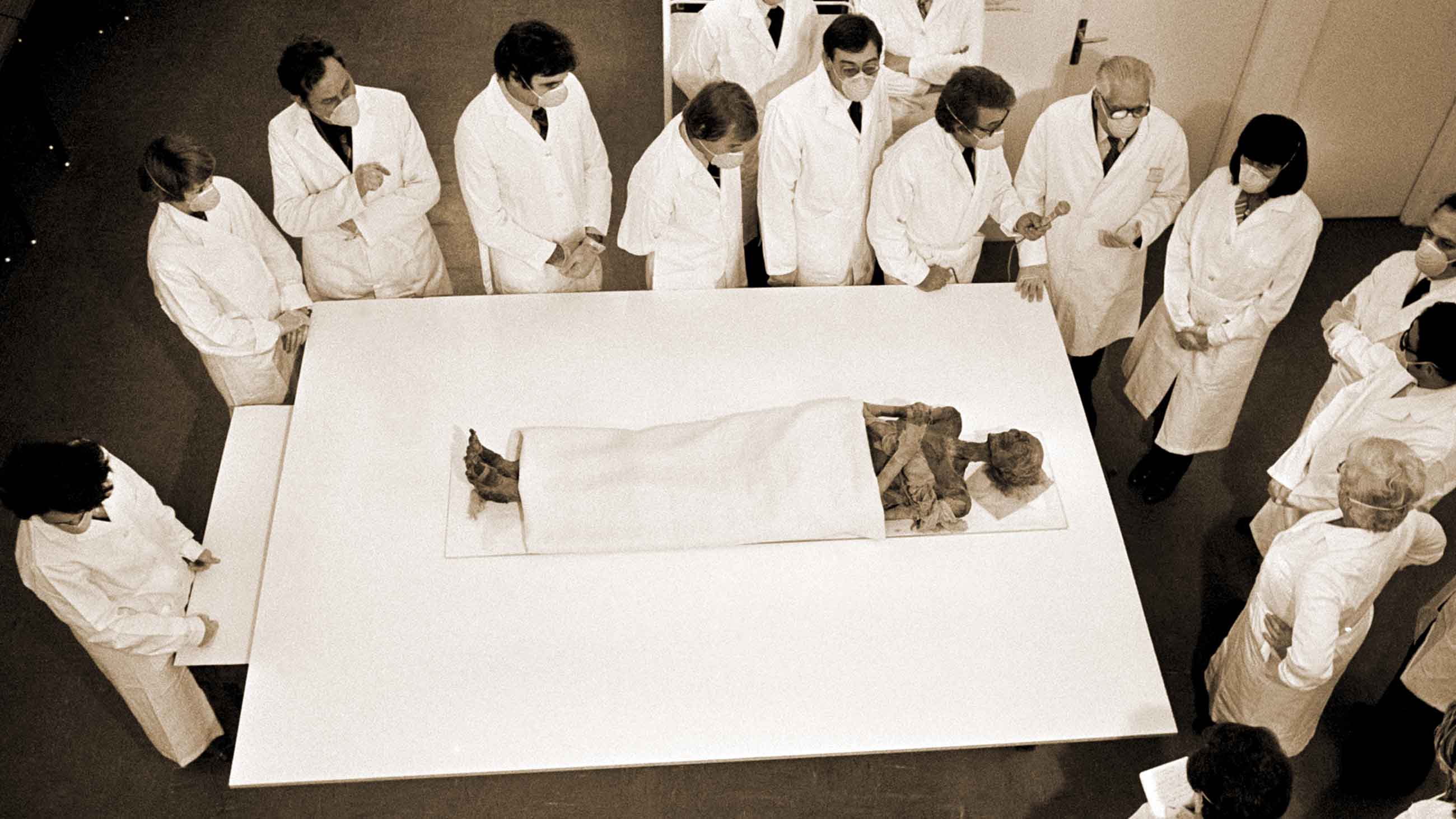

For all of the many dimensions to the controversy, challenges to the quality of the science itself have most dogged the Atacama paper and its authors. That the researchers even wondered whether the remains were human speaks to their lack of expertise, several experts said. After all, a 2007 examination of the remains by Francisco Etxeberria, a Spanish medical doctor and professor of legal and forensic medicine at the University of the Basque Country, had already concluded they were human. “It’s easy to realize that it’s a mummified fetus,” Etxeberria said — pointing to things like the remnants of umbilical cord as a clear giveaway.

It’s not entirely clear whether Nolan knew of Etxeberria’s findings (Etxeberria said he has not directly communicated his findings with Nolan), but he stated in a 2013 interview with OpenMinds.tv that he did not believe the remains were from a fetus, and instead trusted the estimated age of six to eight years old from his colleague and coauthor on the paper, pediatric radiologist Ralph Lachman, who examined x-rays and photographs.

And as for “skeletal abnormalities,” Etxeberria and other experts say there aren’t any. The bones’ characteristics are consistent with remains mummified by the dry conditions of the Atacama Desert, for example, and the presence of only 10 ribs is entirely consistent with a fetus of that age (full-term babies and adults have 12). He added that he found the claims of skeletal abnormalities particularly worrying, as they suggest “professional negligence.”

Halcrow also noted that even if one were to assume the fetus had abnormal skeletal traits, the gene variants identified to explain the mummy’s appearance make no sense, as they wouldn’t affect a fetus that young. She, along with several colleagues, raised these fundamental scientific issues with the editors of Genome Research, hoping for an opportunity to publish a rebuttal — the usual channel for scientific critiques. But to date, the journal has refused to publish criticisms of the study’s science, as they claim the journal “publishes only peer-reviewed research.”

Genome Research did publish both a letter from Nolan and Butte responding to ethical criticisms, and a statement from the journal’s editorial board last spring.

Halcrow and her colleagues have since sent their critique to another journal, the International Journal of Paleopathology, which reviewed and published it in July. The rebuttal paper doesn’t mince words, calling the Genome Research study “a prime example of how research that is not rigorous, analytically sound, or performed by appropriately trained researchers can spread misinformation,” and that “studies such as these that do not address ethical considerations of the deceased and their descendant communities threaten to undo the decades of work anthropologists and others have put in to correct past colonialist tendencies.”

Nolan and Bhattacharya declined a request for comment on the rebuttal, but a policy paper published in the journal Science a month after the Atacama study lays out clear ethical guidelines for paleogenomicists that might have been helpful to Nolan and his colleagues. They include identifying the indigenous communities relevant to the study, consulting with them prior to, during, and after the analyses are conducted, and having clear plans for what happens to samples after the research concludes.

Institutions and scientific journals could also take this time to reflect on incentives.

“Having real repercussions for researchers who violate ethical standards is a key part of this puzzle,” Colwell said.

Universities and funding agencies currently impose sanctions for research misconduct, ranging from reprimands to termination or being barred from funding, but ethical violations independent of legal requirements aren’t clearly included in such policies. Part of the problem is that ethical codes vary widely by research discipline. The idea that scientists conducting research on human remains were unaware of practices in fields like anthropology and archaeology should indicate that codes of ethics need to be as interdisciplinary as modern scientific research has come to be.

Right now, there appear to be few gatekeepers to prevent unethical research from receiving funding, being conducted, or even being published — an “ethical vacuum,” as Kakaliouras described it. And even when ethical issues are identified, differing policies between journals and institutions, and the thicket of national and international laws and regulations, make it unlikely that the scientists will be dissuaded from questionable practices.

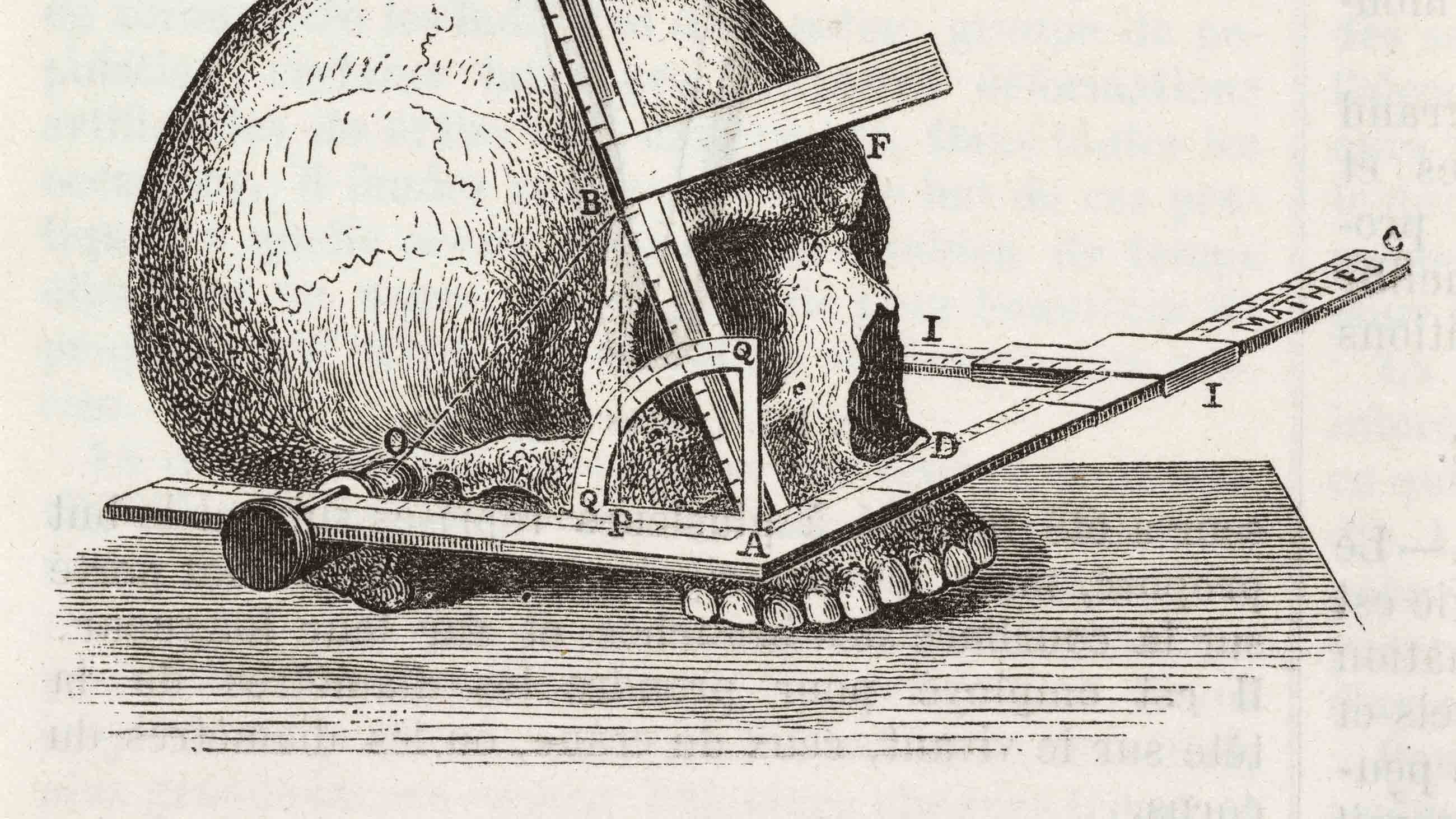

According to Colwell, we’re in the middle of a “bone rush,” where geneticists around the world are “racing to make the next headline.” Rapidly improving technologies have made it easier to extract and sequence DNA from even the smallest fragments of ancient bones, and geneticists are eager to use these advanced techniques to learn from the past in ways no one could have dreamed of a century ago. And while the ability to sequence whole genomes and make incredible discoveries is exciting, he says now is the time for a full and open dialog on the proper way to conduct — and publish — such research.

“I think if we don’t pause right now to ask these questions, we’re just going to see history repeating itself,” Colwell said. “We’re just leaving the next generation of researchers mountains of ethical dilemmas that they’re going to have to solve.”

Christie Wilcox is a science writer and author of the 2016 book “Venomous: How Earth’s Deadliest Creatures Mastered Biochemistry.” Her work has also been published by Quartz, Scientific American, Discover, and Gizmodo, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

How did the remains come up for sale? Who sold the remains? Who loots and sells and profits from this? It’s not always foreign museums who take artefacts from the ground. Often it’s local looters, robbers and criminals exploiting their heritage as just another resource. Even if we acknowledge the poverty that underlies this, these things don’t happen in a vacuum. It’s an easy narrative to vilify museums and scientists, but in order to buy, there has to be a seller. Corrupt officials look the other way. Sites are destroyed so that no-one gets to celebrate the heritage of humanity. By all means make scientific study transparent and accountable, but look at the whole process from beginning to end. Good people in all countries want to do the right thing, but it needs to be examined as a whole in order to be fixed.

One may have a moral right to artifacts but unless that moral right is backed up by an army it may be almost meaningless.

Western institutions and individuals are the greatest culprits of cultural looting. Go to any western museum they are all filled with STOLEN artefacts that belong elsewhere. Go to the Museum at Buckingham palace, it screams “We looted these and we are proudly displaying the loot”. The same with British Museums, French, German, American, Dutch – you name it.

The west is in effect declaring that looting rape and murder is a special right of teh west.

Shame.