What Makes Some Species More Likely to Go Extinct?

Though they say “‘tis impossible to be sure of anything but death and taxes,” a bit of financial chicanery may get you out of paying the taxman. But no amount of trickery will stop the inevitability of death. Death is the inescapable endpoint of life.

VIEWPOINTS

Partner content, op-eds, and Undark editorials.

And this is as true for species as it is for individuals. Estimates suggest 99.99 percent of all species that have ever lived are now extinct. All species that exist today — including human beings — will invariably go extinct at some point.

Paleontologists like me know there are key moments in Earth’s history when extinction rates are high. For example, researchers have identified the Big Five mass extinctions: the five times over the past half billion years or so when more than three quarters of the planet’s species have gone extinct in short order. Unfortunately, we are also now getting a good firsthand view of what extinction looks like, with the rapid increase in extinction rates over the last century.

But what factors make any one species more or less vulnerable to extinction? The rate of extinction varies between different groups of animals and over time, so clearly not all species are equally susceptible. Scientists have done a great job of documenting extinction, but determining the processes that cause extinction has proved a bit more difficult.

Looking at modern examples, some tipping points that lead to the extinction of a species become obvious. Reduced population sizes is one such factor. As the number of individuals of a species dwindles, it can lead to reduced genetic diversity and greater susceptibility to random catastrophic events. If the remaining population of a species is small enough, a single forest fire or even random variations in sex ratios could ultimately lead to extinction.

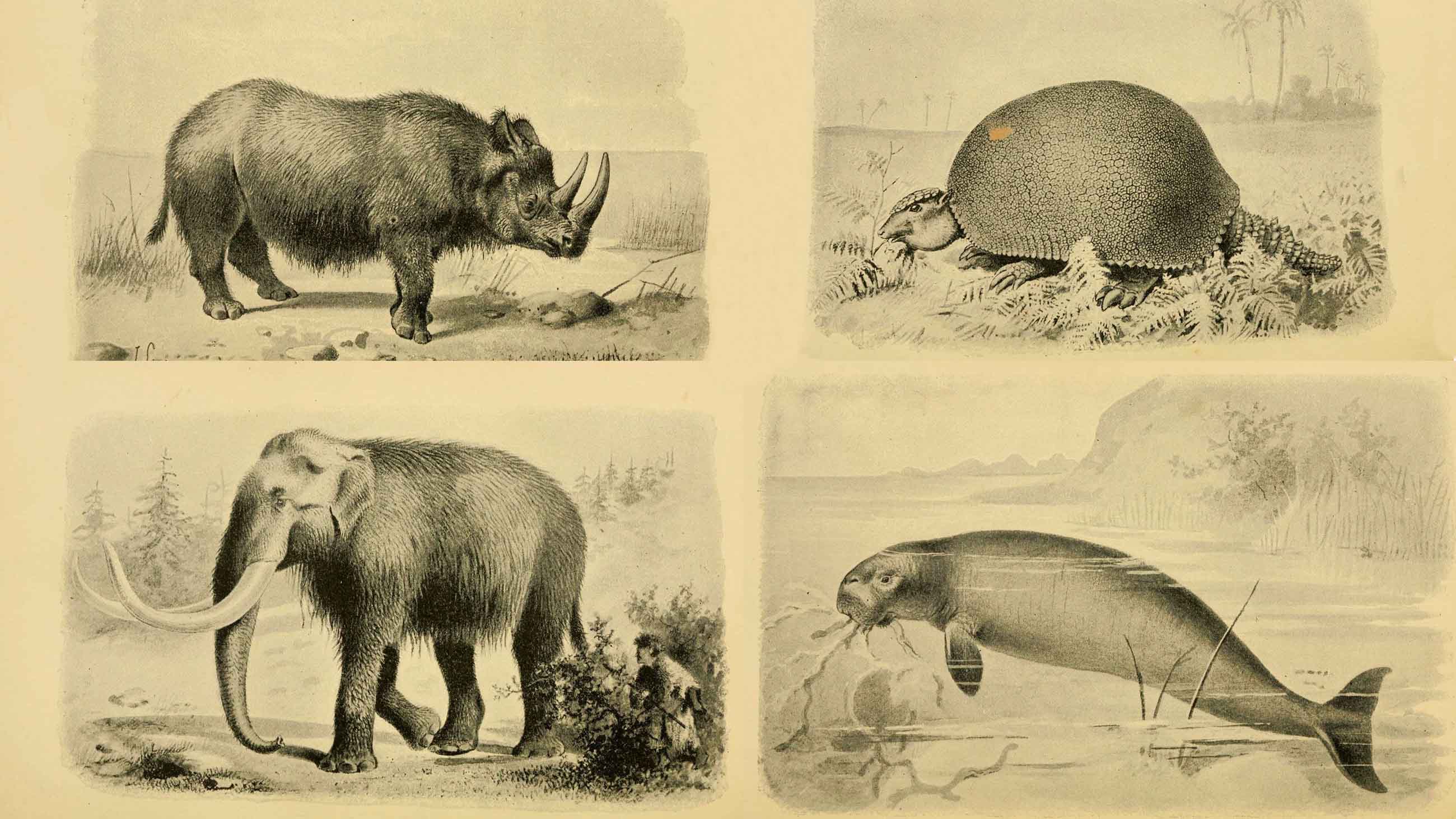

Extinctions that have occurred in the recent past receive a great deal of attention — for example, the dodo, thylacine, or passenger pigeon. But the vast majority of extinctions happened well before the appearance of humans. The fossil record is thus the primary source of data on extinction.

When paleontologists consider fossils in the context of what we know about past environments, a clearer picture of what causes the extinction of species starts to emerge. To date, the likelihood of extinction of a species has been linked to a host of factors.

We certainly know that changes in temperature are one important element. Almost every major rise or fall in global temperatures in Earth history has resulted in the extinction of a swath of different organisms.

The size of the geographic area a species occupies is also crucial. Species that are broadly distributed are less likely to go extinct than those that occupy a small area or whose habitat is disjointed.

There are also random phenomena that cause extinction. The meteorite responsible for the extinction of about 75 percent of life at the end of the Cretaceous Period, including the non-avian dinosaurs, is perhaps the best example of this. This random aspect to extinction is why some have argued that “survival of the luckiest” may be a better metaphor for the history of life than “survival of the fittest.”

Most recently, my colleagues and I identified a physiological component to extinction. We found that the representative metabolic rate for both fossil and living mollusk species strongly predicts the likelihood of extinction. Metabolic rate is defined as the average rate of energy uptake and allocation by individuals of that species. Mollusk species with higher metabolic rates are more likely to go extinct than those with lower rates.

Returning to the metaphor of “survival of the fittest/luckiest,” this result suggests that “survival of the laziest” may apply at times. Higher metabolic rates correlate with higher mortality rates for individuals in both mammals and fruit flies, so metabolism may represent an important control on mortality at multiple biological levels. Because metabolic rate is linked to a constellation of characteristics including growth rate, time to maturity, maximum life span and maximum population size, it seems likely that the nature of any or all of these traits play a role in how vulnerable a species is to extinction.

As much as scientists know about extinction drivers, there’s still a lot we don’t know.

For instance, some proportion of species go extinct regardless of any major environmental or biological upheaval. This is called the background extinction rate. Because paleontologists tend to focus on mass extinctions, background extinction rates are poorly defined. How much, or how little, this rate fluctuates isn’t well-understood. And, in total, most extinctions probably fall into this category.

Another problem is determining how important changing biological interactions are in explaining extinction. For instance, extinction of a species may occur when the abundance of a predator or a competitor increases, or when a crucial prey species goes extinct. The fossil record, however, rarely captures this kind of information.

Even the number of species that have gone extinct can be an enigma. We know very little about the current or past biodiversity of microorganisms, such as bacteria or archaea, let alone anything about patterns of extinction for these groups.

Perhaps the biggest mistake we could make when it comes to assessing and explaining extinction would be to take a one-size-fits-all approach. The vulnerability of any one species to extinction varies over time, and different biological groups respond differently to environmental change. While major changes in global climate have led to extinction in some biological groups, the same events have ultimately led to the appearance of many new species in others.

So how vulnerable any one species is to extinction due to human activities or the associated climate change remains sometimes an open question. It is clear that the current rate of extinction is rising well above anything that could be called background level, and is on track to be the Sixth Mass Extinction. The question of how vulnerable any one species — including our own — may be to extinction is therefore one scientists want to answer quickly, if we’re to have any chance of conserving future biodiversity.

Luke Strotz is a post-doctoral researcher in invertebrate paleontology at the University of Kansas.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

“extinction of a species may occur when the abundance of a predator or a competitor increases”; one sad example maybe the British red squirrel, succumbing to competition from the American grey squirrel. If so, that would be a special case of the extinction arising from the merging of habitats, a phenomenon known from the aftermath of formation of the central American isthmus, and now, thanks to species hitchhiking on human transport, occurring worldwide.