The evening of April 3, 1968, should have been a triumphal moment for Stanley Kubrick, the pinnacle of a career that in little more than a decade had vaulted him into the ranks of the world’s most celebrated directors. His latest opus, “2001: A Space Odyssey,” was premiering at New York’s Loews Capitol Theater, in a glittering invitation-only event for film industry and media elite, studio big shots, and movie stars including Paul Newman and Henry Fonda. The much-anticipated follow-up to his international hit “Dr. Strangelove,” it was a project he’d been working on for four years, conceived with the science-fiction master Arthur C. Clarke. “2001” was going to be the ultimate sci-fi film, the work that would finally banish the B-movie tropes of bug-eyed monsters and juvenile potboiler adventure and elevate the genre into cinematic maturity.

BOOK REVIEW — “Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece,” by Michael Benson (Simon & Schuster, 497 pages).

Not long into the first half of the nearly three-hour-long film, the boos began. And the jeers. And snide comments like “Let’s move it along,” as the star, Keir Dullea, jogged interminably around the centrifuge of the spaceship Discovery. People who had been merely squirming in their seats began walking out; by the end of the screening, well over 200 had departed. Clarke overheard a comment from an executive from MGM, the studio whose $12 million Kubrick had just spent: “Well, that’s the end of Stanley Kubrick.”

As Michael Benson describes in “Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece,” Kubrick may not have overheard that particular remark, but he had apparently reached much the same conclusion. After attending a post-premiere reception that felt more like a wake, the devastated director retreated with his wife, Christiane, to a rented Long Island mansion, where he continued to agonize into the night before finally falling into an exhausted sleep, his supreme self-confidence in his vision and ability apparently gone. Along with, it seemed, his career.

But Christiane would awaken Kubrick to a radio report of huge lines waiting to get into “2001” and extravagant praise for a “fantastic film.” Kubrick’s not-so-long dark night of the soul was over, and as Benson’s subtitle affirms, “2001” had begun its rise to its now legendary status as a masterpiece that forever changed the art of film.

The ascension wasn’t exactly smooth — certainly not in the immediate aftermath of “2001”’s premiere and general release, when most influential film critics seemed to go out of their way to dismiss it as “a major disappointment,” “a thoroughly uninteresting failure,” and even as “trash masquerading as art.” It was the public that made Kubrick’s opus a bigger hit than MGM’s previous blockbuster, “Doctor Zhivago.” Critical reaction eventually softened (and in some cases reversed) after Kubrick recut and trimmed the film. In the ensuing years, “2001” became the benchmark, the gold standard of science fiction film, profoundly influencing generations of filmmakers such as Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott, and Christopher Nolan, some of whose works in the genre would approach but never quite equal Kubrick’s achievement.

But even before anyone outside of Kubrick’s tight circle saw a single frame, Benson writes, “2001” had a bumpy ride from inspiration to fruition. Getting started wasn’t too difficult; determined to make “the proverbial ‘really good’ science fiction movie” and fascinated by the possibilities of extraterrestrial life, Kubrick immersed himself in research, as was his habit. “Kubrick treated every film as a grand investigation,” writes Benson. “Once he’d decided on a theme, he subjected it to years of interrogation, reading everything and exploring all aspects before finally jump-starting the cumbersome filmmaking machinery.” He’d done it with “Dr. Strangelove,” creating a satiric portrait of nuclear madness so uncannily accurate that it made Pentagon strategists fear he had insider knowledge. Now he sought to do the same with the even more profound question of humanity’s place in the universe.

When he reached out to Arthur C. Clarke (who despite his fame had never had a book adapted for the screen), the author and director hit it off famously: two unique geniuses coming together to discuss life, the universe, and everything; to stargaze from Kubrick’s Manhattan penthouse; and to begin to create the story of “2001.” Their creative relationship — ultimately symbiotic if sometimes tumultuous, even litigious, thanks to Kubrick’s repeated delays in clearing final publication of Clarke’s novelization (and his payment) — dominates the making of “2001” and Benson’s book.

Yet it was one thing to ponder lofty conceptions and deep insights about humanity and the universe, and quite another to manifest them in physical reality, with all the limitations of 1960s film technology and studio production budgets. It’s here that Benson’s book really shines. There’s no shortage of literature on the minutiae of “2001”’s special effects, the creation of its sets and models, and the technicalities of camera lenses and film stocks. But while Benson provides enough detail to satisfy the most obsessive film geek, he never loses sight of the human story: the egos, short tempers, and personality conflicts that sometimes threatened to derail, if not completely scuttle, the project. And he makes clear that Kubrick and his legion of artists (calling them “technicians” seems somehow inadequate) weren’t simply coming up with cool effects. They were, in fact, inventing an entirely new visual vocabulary.

Still, few of them realized how important a film they were making. (One exception was the actor Gary Lockwood, who was always convinced that he’d lucked into the “greatest film ever made.”) While most felt they were working on something special, or at least unusual, they had more than their share of qualms, anxieties, and doubts — including Kubrick himself.

Though he was careful never to let slip any sign of self-doubt or indecision on set or with his staff, Kubrick would sometimes drop that veneer of confidence after a long day’s work at the studio, when safely at home with Christiane. “I don’t know what I’m doing, I have no idea!” he would lament. Benson quotes Christiane: “He looked like he didn’t doubt himself, yes. But he so did. He had these ‘I’m just an asshole’ moments all the time.”

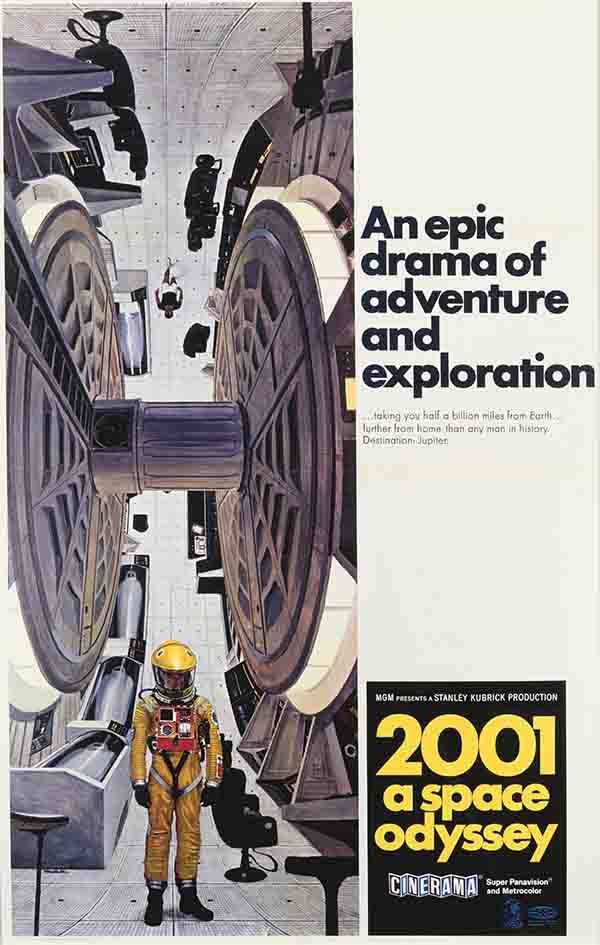

A 1968 poster for the movie, showing the 38-foot-tall centrifuge that nearly killed a visiting MIT scientist.

Visual: Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images

Despite Kubrick’s well-earned reputation for meticulous planning and exhaustive research, some of Benson’s most startling revelations show that much of “2001” wasn’t the product of measured creation but random suggestion and on-the-fly inspiration. After agonizing at length about how the murderous computer HAL 9000 could convincingly discover astronauts Bowman and Poole plotting against him, Kubrick found the answer in a casual suggestion from associate producer Victor Lyndon: HAL could just read their lips. When actors in ape suits for the “Dawn of Man” sequence inevitably looked too much like, well, actors in ape suits, Kubrick accepted the advice of an American mime, Dan Richter, who in collaboration with the makeup wizard Stuart Freeborn used his performance skills to create prehistoric hominids so convincing that many of “2001”’s audience believed them to be actual trained primates.

Other effects were not so much serendipitous as outright dangerous. Some involved the spaceship’s huge centrifuge (whose spin would simulate Earth’s gravity for Discovery’s crew), a 38-foot-tall structure capable of rotating a full 360 degrees on its edge. Which meant that if something inside it wasn’t securely fastened down, it wouldn’t stay put when the set was rotated — as the MIT artificial intelligence expert Marvin Minsky learned when he visited the set and was nearly killed by a falling pipe wrench. It would have been an ironic demise for a man whose pioneering research had informed the creation of the self-aware HAL.

Now that we’re well past the year 2001, it’s become an annoying, even depressing, truism to note that “2001”’s sprawling moon bases and elegant spinning-wheel space stations are nowhere to be seen. For decades after its debut, “2001” seemed prophetic, a glorious vision of a brilliant future. When I first saw the film at age 8, I was already scheming to get a ticket on a Pan Am Space Clipper, just as soon as regular service began and I’d saved enough of my allowance. I was far from alone in that ambition. Yet “2001” now represents far more than merely another grandiose yet failed sci-fi vision, like the flying cars, personal jetpacks, and household nuclear plants we’ve always been promised but will never have.

As Dullea’s character, Dave Bowman, is transformed by the end of the film into a new being, the next step of sentient evolution, an entity with capabilities and potential yet to be discovered, so Kubrick, through “2001,” transformed film art itself to the next level, not just technically but artistically, thematically, even philosophically. In the universe of the movie, the never-seen intelligences behind the monolith provide the evolutionary spark, beginning with its first appearance in the “Dawn of Man” and culminating with Dave Bowman’s surreal transformation “Beyond the Infinite.” In our own universe, it was the singular combination of the restless, far-reaching intelligence and imaginations of Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke that sparked the next evolutionary step of cinema. With “Space Odyssey,” Michael Benson has given us the best explanation of how it happened.

Mark Wolverton is a science writer, author, and playwright whose articles have appeared in Undark, Wired, Scientific American, Popular Science, Air & Space Smithsonian, and American Heritage, among other publications. His forthcoming book “Burning the Sky: Operation Argus and the Outer Space Nuclear Tests That Turned the Earth Into ‘The Greatest Experiment of All Time’” will be published in November 2018. In 2016-17, he was a Knight Science Journalism fellow at MIT.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I saw the original Cinerama curved-screen roadshow at the Summit Theatre in Detroit…… April 1968. After the film ended, my parents walked out of theatre saying: “What the hell was that we just saw?”. Meanwhile, I’m walking out of the theatre with a huge smile on my face as if I had just seen God. It was a moment I’ll never forget.

That was almost exactly my response as I and my friends exited the Cinerama theatre in Louisville. It’s as if you the viewer have also taken an evolutionary leap. For those of us who were open to it, it was a life-changing event.

What makes “2001” unique among not just science-fiction movies but movies in general is that Kubrick the filmmaker chipped away all the intellectualized answers Clarke wrote into the book, like the narration, humanoid alien in the “Dawn of Man” sequence, etc. The result is a movie that can be watched on a purely visceral level. Any interaction between humans and a vastly more ancient intelligence is likely to be puzzling, perhaps even inexplicable. Somehow, with 1960’s technology, Kubrick manages to get this across on the screen by showing us, not telling us. It’s a great achievement of story telling, in my opinion. Best enjoyed in a theater in 70mm release!

The Hollywood Theatre in Portland recently acquired a 70mm print of the film thanks to donations from its membership and others. The cost was $25,000. They regularly schedule “2001” to sold-out audiences. I’m looking forward to experiencing it again in a venue other than television!