On an unremarkable morning in September of 2010, Abby Norman, a sophomore at Sarah Lawrence College, took a shower. Going through the motions, still mostly asleep, she reached to rinse her hair. “It was as sudden as a thunderclap,” she writes. “A stabbing pain in my middle, as though I were on the receiving end of an unseen assailant’s invisible knife.”

BOOK REVIEW — “Ask Me About My Uterus: A Quest to Make Doctors Believe in Women’s Pain,” by Abby Norman (Nation Books, 288 pages).

Norman spent the better part of a week willing herself to get better; college was the first place she had felt at ease, and her scholarship and means for staying in New York were contingent on keeping up with her classes. Still debilitated after two trips to the emergency room, where she was prescribed antibiotics and then told she should see a gynecologist, Norman began to realize she might need to take a leave.

This narrative — reconstructed from social media posts, journal entries, and emails to professors — forms the opening of Norman’s debut book, “Ask Me About My Uterus,” which recounts her long and agonizing battle with the poorly understood pelvic pain disorder called endometriosis. What began as a chronicle of her transition from dancer and student to determined patient grew into a book documenting her experience with a mysterious chronic illness, woven with the flaws she observes in the treatment of a disease that plagues at least one woman in 10.

An invisible illness, it can elude years of diagnoses by multiple doctors. There is no reliable blood test, no imaging scan, no urine dip. From the outside, people with endometriosis appear normal. In the days after the episode in the shower, Norman herself was surprised by how completely she hid the searing pain from her roommate. The diagnosis relies on narrative, yet patients find their stories doubted. In Norman’s words, “I was the primary source of data for the investigation into my condition, and yet it often felt like the data I presented was questioned by others as unreliable, which made me question myself.”

When Norman finally undergoes surgery to untwist her fallopian tube, the most immediate source of pain, the gynecologist mumbles something about noticing endometriosis, a comment in the margins of Norman’s operative report. What both her surgeon and the doctor failed to explain was that endometriosis does not resolve on its own, and that if left untreated, it could continue to cause excruciating pain.

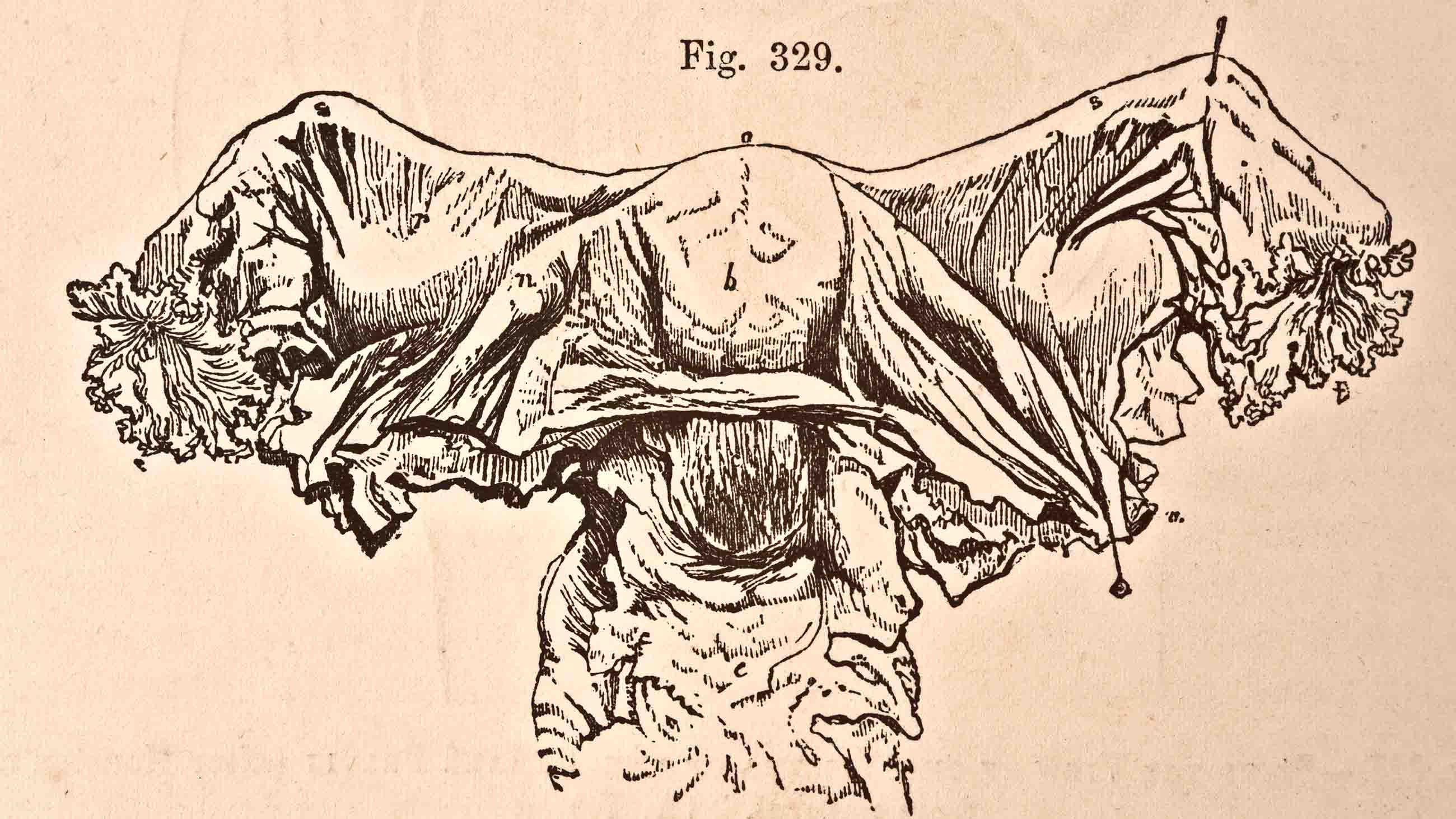

Endometriosis is commonly understood as cells similar to those of the uterine lining ending up on other organs, leading to inflammation, scarring, and lots of pain. Women are frequently diagnosed when they are unable to conceive, though endometriosis does not necessarily cause infertility, nor is it cured by pregnancy. Recent research demonstrates that endometriosis exists even in female fetuses, but pernicious misinformation stands in the way of a correct diagnosis, especially in girls who haven’t begun to menstruate, women with no interest in childbearing, and transgender men.

Norman identifies a more pervasive obstacle to proper care: a medical system that doubts, ignores, or normalizes women’s pain. Framing endometriosis as a social justice issue explains why botched diagnoses and therapy abound, and why the dominant view of causes and treatment is the one established by men in the 1920s. The misogyny unearthed by #MeToo is prevalent not only in interactions with adults, employers, and disbelieving doctors, but in the way that grant money is doled out to study diseases whose symptoms are accepted as part of “being a woman.” A simple PubMed search reveals a roughly equal number of articles on male-pattern baldness as on endometriosis, though only one of these conditions can cause an individual to miss work or drop out of school.

‘Ask me About My Uterus” summons powerful testimony from Jhumka Gupta, an epidemiologist whose own bout with endometriosis points up the gender imbalance that informs society’s response to the disease. Even though Gupta’s professional work centers around reducing violence against women, she too found herself unable to speak up about her own health; in an address to the Endometriosis Foundation of America, she recounted scoping out a discreet place to vomit while on a research trip, trying to minimize and mask her symptoms.

While Norman’s subtitle is “A Quest to Make Doctors Believe in Women’s Pain,” the memoir form doesn’t always serve that commendable purpose. There is scant discussion of other women, few interviews with doctors, and no direct input from historians or sociologists. This isn’t entirely Norman’s fault, because the medical community and the news media too often fall back on outdated clichés. From her reading, she observes, passages on endometriosis “can read like college term papers written the night before they’re due, wherein a lot of unnecessary words are added to make the paper longer.”

Perhaps for that reason, Norman spends more time discussing her past. It’s an inspiring story: Raised in a trailer by a mother consumed by bulimia, she became emancipated at age 16 and studied hard enough to win admission to a topflight college. She is now an accomplished writer who manages life with chronic illness., And whatever its flaws, this book elevates the experiences of women who come to appointments with reams of internet print-outs only to be told not to Google their symptoms. A book, published with endnotes, validates this process of self-study, and might reach others struggling against an apathetic medical system.

In the end, though, it’s regrettable that “Ask Me About My Uterus” will likely circulate most among those with their own lived versions of this story — people who don’t need convincing that doctors tend to fall back on “this is all in your head.”

Kate Telma is a freelance writer based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a recent graduate of the MIT Graduate Program in Science Writing.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Hello I’m from Spain.

When i firts got my period at the age of 14 and i was screaming of pain they told me to “keep it together”. As someone so young i couldn’t understand how to be quiet about something so painful.

Growing up, i didn’t need to keep track of my cycle. I knew when I was going to have it, because a week or 5 days before, when I accelerated my walking, I ran or jumped … any movement would make me writhe in pain, leaving me immobilized sitting on a bench, the street, or in class, hoping the pain would go away after taking painkillers and antiinflammatories.

I went consulting with doctors and gynecologists, always deviating me from one professional to another. Never taking seriously my case. It is not normal what happened to me or what happens to me. Now I’m an adult, I’m tired of being treated like a crazy woman.

Earlier this year, the day before getting my period, I began to feel a terrible pain, knives in my uterus? NO worse! i felt as if someone was tearing me apart, how someone was opening my uterus with a knife and after gutting me alive twisting my uterus with their bare hands like an animal going to a buthcer… I started screaming as if i was getting murdered. It sure felt like It!!

I was soaked, I couldn’t move and I got dizzy and vomited from the pain, my brothers came to my help. THey found me lying on the floor of the bathroom white like a gosht, (i have a dark skin so imagine) i never saw my brothers so scared. i was shaking, having small convulsions with every wave of pain. When they tried to make me stand up to dress me up, the pain was so intense that I would faint and throw up (apparently you can do both at the same time…), so I was in my own personal hell for 1hr until i arrived to the hospital and they sedated me.

I had never felt so much pain in my entire life. The doctors told me that my body had reached the maximum physical tolerance of pain and that to protect myself from such torture, my body decided to disconnect my organs, (intestines) and my head (losing consciousness). I fainted to protect myself from pain. And I ask myself… is it normal to feel a pain so big that your body just collapses? It is not, but gentlemen. the doctors just want to give me painkillers !!! they tell me that women are like that, some are luckier than others… and that with hormones (contraceptive pills) the pain will go away … I’ve been taking anticoceptive pills for 5 months and when I get my period I’m still dying inside. When I go to the hospitals, they look at me badly. Because men are not the only ones who do not understand this pain, but also women who don’t suffer of it. They believe that we are weak and exaggerated when in fact we are the most outcast women who conceal and tolerate such suffering. Gynecology has to advance more and also the study of pain.

This article highlights, quite well, one of the seminal problems in medicine (of which there are many). But it unfortunately casts it in a sexist light, i.e., not believing women’s personal reports of pain. In fact, the problem of not believing patient’s own accounts of their situation is a major problem in medicine irrespective of sex. Medical doctors, in contrast to common perceptions, rarely, very rarely, actually listen to what their patients say to them and believe even less. They have a knee-jerk response to what is presented to them and routinely, as in this case, prescribe antibiotics when they have no idea of what is wrong (something specifically proscribed in practice due to the rise of resistant bacteria). Very few physicians actually sit with their patients, listen to what is wrong, and then spend the time, however long it takes, to understand the unique ecological entity in front of them and track the symptoms back to an originating dynamic. The vast majority prescribe interventions based on superficial understanding of the condition with which they are presented. Most people then receive medical interventions that not only do not help but in many instances actually harm. A cursory look at easily accessed peer review articles on such sites as pubmed makes plain how common this is. As only one example, people with Lyme disease generally see a minimum of 5 physicians over 2.5 years before an accurate diagnosis is made. During that time each of them will be diagnosed with many unrelated conditions (from bi-polar to depression to schizophrenia to arthritis to MS to chronic fatigue and so on and on). The medical system is broken and in fact exists for only one reason, to make money for the medical/pharmaceutical/industrial complex. This article highlights one symptom of that but attributes it to not hearing women’s personal reports of pain.

You actually mansplained on an article like this. Listen, George, I get that all doctors need to do better with listening and actually caring. However, your comment here is not only off topic but illustrates the kind of ridiculous way people suffering from endo are constantly talked over. Sit back, read, and think. I know it’s tough when things aren’t all about you, but you could learn something if you shut up for two minutes.

From my very first period, there was pain – can’t get comfortable, can’t breathe pain. I was 2 months shy of 13. The pain lessened afterwards, but never really left. It became a constant dull ache I tried to ignore, until the next month when the pain gripped me again. Aspirin could take the edge off it for a couple of hours, but it always came back. I was made to feel like a weakling by my own mother who told me to “try sports, you’re too sedentary.”.

After a visit to my primary care provider ( who asked me “are you SURE you’re not pregnant?) and a colonoscopy due to family cancer history, I saw the greatest OB/GYN I’d ever met. SHE asked why I’d waited so long to have a hystorectomy. SHE told me the pain WASN’T normal. I was 41 and ever so glad to be done with the whole mess! For about the first six years, I would still have some pain near where my cervex had been- usually after eating popcorn (?!).

I’m 51 now and am having bladder control issues. I limit my liquid intake and that helps. Also, I don’t drink anything after 6PM.

Most days are pain free, but I still get hot flashes and night sweats. And there’s irritability and mood swings.

Oh! And sex is painful. I’ve been celebate most of my adult life because of the pain. Love shouldn’t hurt.

My wife went through this when her blood pressure skyrocketed (250/110). Her urethra was constricted, as it turned out, by endometriosis. And this was several years after a full hysterectomy and surgery for endometriosis. It turns out, hormone replacement therapy can also encourage the growth of endometrial cells, just as a normal hormonal cycle can.

A noble effort to shed light on a terrible condition, but for all its passion I wish the writer had given us more information. What does medicine really know about endometriosis? What causes it? What are the available treatments? What, for example, should that surgeon who realigned the Fallopian tube have done, or recommended, when he spotted the endometrial cells? And what does the word endometriosis actually mean! These are some of the questions I would like to have seen answered in a science- based website.

I want to thank you for the book and the attention to endometriosis. I suffered throughout my teens and twenties with endometriosis, through nursing school and then stayed at home to cope with a disease that left me in pain all month long. I had two ablations and then finally a hysterectomy at 31. That, my lack of self-confidence, and PTSD from all I’d been through (plus an abuse history) kept me from having the kind of career most women would have had even though I trained as an RN and had worked for several years until the disability got too great.

Finally, later in life I got two master’s degree and worked in a hospice for six years. the only ‘good’ that came out of it was the ability to counsel and sit with people in their pain and suffering. Endometriosis made me acutely aware of human suffering and led me to study Buddhism and to develop compassion for myself and others. Now, 74 I reflect on my life and all I might have done (and what I might have earned to help fund our retirement). I lead two Parkinson’s disease support groups and have a local cable access show. My husband has PD and I am his full-time caregiver.

Thank you for doing the kind of giving back that I try to do.

While I agree that “…“Ask Me About My Uterus” will likely circulate most among those with their own lived versions of this story” I still want to say there’s great value in this effort. Where women have been dismissed by the medical establishment, reading memoirs, essays, even comments or postings on social media is a helpful form of incremental consciousness raising. This is the stuff of #metoo, and is important as one of the ways we can bring our stories to light and bring pressure on that establishment.