The Enduring Appeal (and Folly) of Disease Eradication

For decades now, global health organizations and deep-pocketed philanthropies like the Gates Foundation have worked to eradicate wild poliovirus — and the achievement of that goal often seems tantalizingly close at hand. In 1988, the year the global eradication campaign officially began, there were more than 350,000 cases of naturally occurring, or wild polio in 125 countries. Last year, only 22 cases of wild polio were reported in just two countries — Pakistan and Afghanistan. Six cases have surfaced thus far in 2018.

VIEWPOINTS

Partner content, op-eds, and Undark editorials.

With the world potentially seeing the end of polio in the near future, global health organizations are turning their attention to another disease: malaria. Since 2000, funding for malaria has exploded, from around $200 million in 2000, to $2.5 billion today. Leading the effort is the Gates Foundation, where malaria is described as “a top priority.” But Bill Gates doesn’t just want to reduce malaria — he wants to eradicate it, just like polio.

Polio and malaria spread in completely different ways, and their effects on the body are nothing alike. But under the banner of eradication, the two diseases have something in common. For eradication to remain viable and keep its unmatched appeal, the world first needs to finish polio. As Gates has described it, eradicating polio is the first step in the even more ambitious plan to conquer malaria.

“Polio, we hope to get done by 2018,” Gates once said. “The credibility, the energy from that will allow us to take the new tools we’ll have then and go after a malaria plan.” That was in 2014. But in 2018, polio eradication has missed another deadline and required yet another round of funding. Overdue and over budget, polio eradication could also fail catastrophically. Oral polio vaccine itself can lead to vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) that could linger for years after eradication of the wild virus. VDPV could ignite huge polio outbreaks of 50,000 cases of paralysis or more and require that eradication start over. Meanwhile, the ongoing campaign is costing donors $1 billion annually.

The concept of eradication is appealing. The simplicity of the idea makes it almost inarguable. Why set any goal for controlling a disease, or reducing its infection by a certain number, if — with enough money and effort — you can get rid of the disease forever? But while the reduction in wild polio is often used, rightly or wrongly, to argue for the validity and power of eradication campaigns, the ongoing and expensive struggle to cover the last mile suggests that there may be a point of diminishing returns. This is doubly true for malaria, given its distinct epidemiology.

Indeed, at a time when leaders in some of the world’s poorest countries are fighting not one but many diseases, truly improving global health may require us to shift our focus away from eradication alone, and to spend some time and treasure helping these nations to build robust health care systems so they can manage diseases that almost certainly will never fully go away.

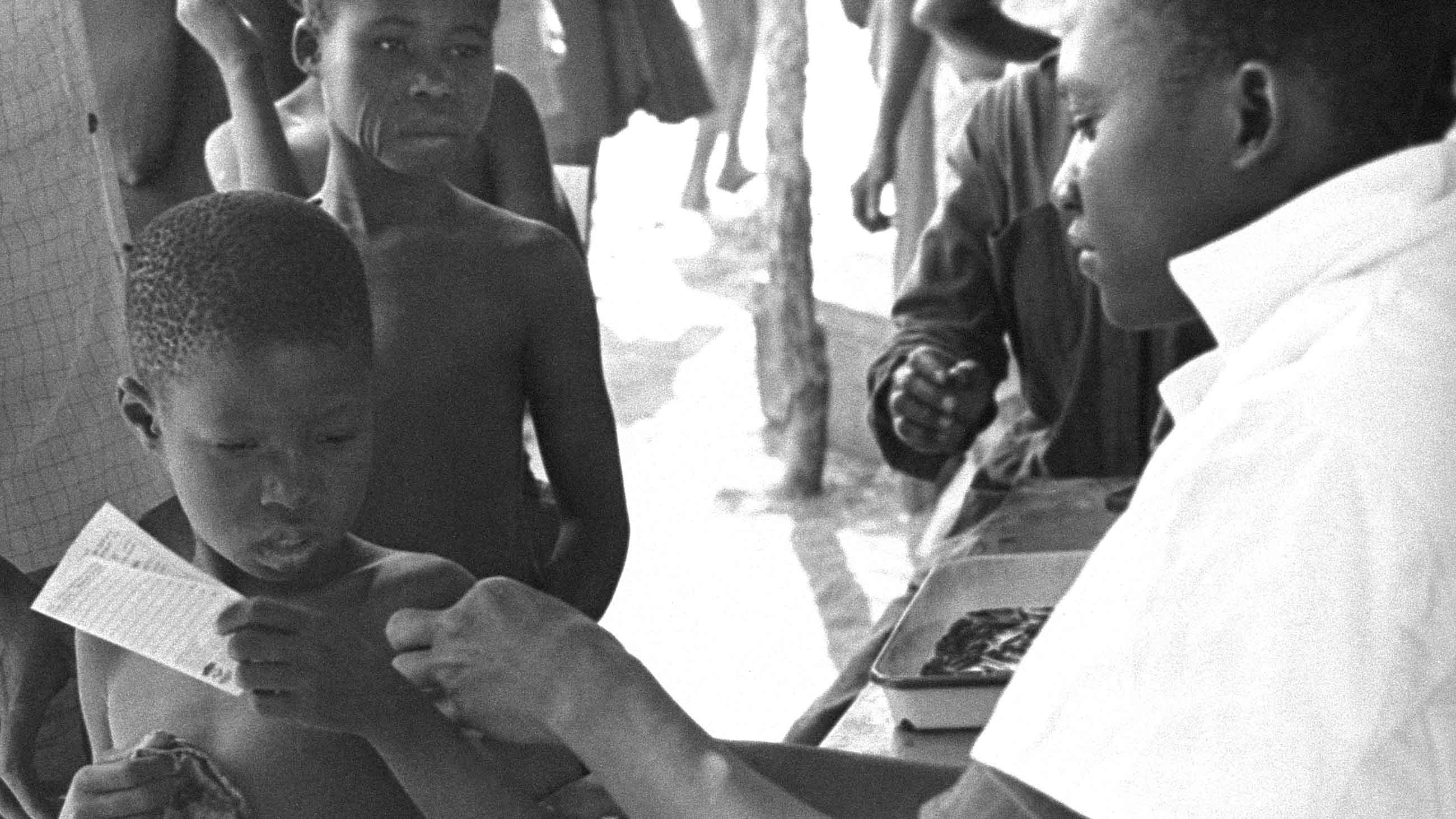

Humans had already been living with malaria for at least 10,000 years when the World Health Organization tried — and failed — to wipe out the disease in the 1950s and 1960s. At the time, the field of genetics was in its infancy, and there was no vaccine for the disease, which is caused by a mosquito-borne parasite that kills hundreds of thousands of people annually. Instead, WHO and its partners targeted malaria’s carrier, the mosquito, by spraying the insecticide DDT in mosquito-rich areas in Europe, the Americas, and South Asia, and cleared the parasite from people by distributing doses of chloroquine, a malaria treatment drug.

Infection rates fell, but so did people’s immunity to the disease. And by relying on a single insecticide, mosquitoes developed resistance to it. After the mid-century campaigns failed, malaria swept back over many areas, often making people more sick than before — and solidifying the scientific community’s near-universal opposition to mounting any further malaria eradication campaigns.

That changed in 2007. At a Gates Foundation event at a Seattle hotel, Melinda Gates, the wife of Bill Gates and co-chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, challenged an audience that included some of the world’s leading malaria specialists to get rid of malaria permanently. “Advances in science and medicine, your promising research, and the rising concern of people around the world represent an historic opportunity not just to treat malaria or to control it,” she said, “but to chart a long-term course to eradicate it.” With the foundation’s leadership, eradication went from anathema to the unofficial goal of the world’s malaria efforts.

Whether this will ever be possible is a matter of debate. Part of the problem is that, unlike polio or smallpox, humans don’t develop a lasting immunity to malaria once their immune systems defeat it. A malaria vaccine called RTS,S showed some early promise, but the results from clinical trials were disappointing. Meanwhile, the existing tools, like mosquito-repelling bed nets, antimalarial drugs, and insecticides, require people’s active participation. Every night in which someone doesn’t sleep under a bed net, or misses a round of antimalarial drugs, eradication becomes harder.

Despite this, advocates for eradication remain sanguine about their prospects. “I think we will see an end to malaria in my lifetime,” Bill Gates wrote in an entry to his Gates Notes series just last year.

But not everyone agrees. “It’s a complete myth that we’ll eradicate malaria in Bill Gates’ lifetime,” said Bob Snow, an expert in malaria epidemiology with the Center for Tropical Medicine & Global Health at the University of Oxford. Snow makes his home in Nairobi, Kenya, and has dedicated his career to fighting malaria in Africa.

Bill Gates discusses the effort to eradicate malaria worldwide, and for good, in 2011.

In October, Snow published a paper in the journal Nature which estimates malaria levels in sub-Saharan Africa since 1900. Although he found “a historically unprecedented decline” in malaria infection rates since 2000, progress slowed after 2010 — even as malaria eradication efforts (and spending) continued to rise. Those findings were echoed in the most recent WHO report, which found that the decline in cases had leveled off since 2013, even though funding had barely changed. Snow called the report brave for its candor. “It would have been very easy with the pressure of Gates and the donors,” he said, “to keep that message out.”

WHO’s report had another unfortunate finding: The number of infections had actually ticked upward by some five million cases since 2014 — the first year that cases have increased since WHO began issuing annual reports in 2005. Researchers are concerned that mosquito resistance to the insecticides used in bed nets might be driving the upturn in cases, not altogether unlike what happened in the 1950s and 1960s, when resistance to DDT contributed to the collapse of the eradication push then.

Whatever the cause, however, this potential rebound points to some of the key problems facing malaria eradication. In polio, a very small handful of long-term carriers of vaccine-derived poliovirus could seed huge outbreaks years after wild polio has been declared eradicated. For malaria, the problem of such silent carriers is many, many times greater. Millions of people are alive today carrying malaria parasites. They are not sick, so they won’t seek treatment, but they are infectious and could reintroduce malaria where massive efforts have successfully eliminated it.

Then there is the fact that there are four species of the human malaria parasite. All of them would have to be eradicated to avoid the risk that one remaining species will replace any of the others that have been already wiped out. In addition, biological differences between the types of malaria mean the tools that might eradicate one species wouldn’t necessarily work for the others. A much larger arsenal would have to be developed.

These stark realities alone ought to give pause to supporters of billion-dollar eradication efforts, but an even more potent reason is this: While infection rates have ticked upward of late, the number of deaths from malaria have continued to go down. That’s because government health ministries, aid organizations, and drug vendors have continued to respond quickly to infections with the drugs that can make them better. After all, if malaria is diagnosed and treated quickly, most people will fully recover.

“No child should die of malaria,” Snow says. “We have the tools.”

The problem is that many poorer areas still don’t have ready access to the medicines that could make people sick with malaria better. That’s why Snow and other advocates argue for a grand repurposing of global public health ambitions with regard to malaria. Instead of spending billions of dollars trying to completely eradicate the disease, that money should be directed at expanding and shoring up local and national health systems.

Health systems are as boring as they are important. Improving them means training health care workers, acquiring medicines, and coordinating data systems and facilities at different levels throughout a country. They can provide routine clinical care, deliver maternal-child health services, and vaccinate people against infectious diseases.

Health systems also increase local capacity to control disease outbreaks, like Ebola. The 2014 outbreak in West Africa led to increased funding for vaccine development efforts. But leaders of the countries which suffered the outbreak want health systems.

“Yes, we want vaccinations,” Guinea’s president, Alpha Condé said at a World Economic Forum event last year. “But we believe with a better performing system, we will not need people to send us international experts. We could do it ourselves.”

Among the world’s health leaders, this line of thinking has gained traction in recent years. Since taking office at the end of 2017, WHO’s new Director-General, Tedros Ghebreyesus has similarly advocated for building up health care. “I think the world should unite and focus on strong health systems to prepare the whole world to prevent epidemics — or if there is an outbreak, to manage it quickly — because viruses don’t respect borders, and they don’t need visas,” he told the American magazine Foreign Affairs last year.

That doesn’t mean that eradication idea is going away. The idea of killing off a disease forever retains an emotional punch that building up basic health care in a poor country never has, and perhaps never will. In a world where eradication is considered a viable option, simply fighting a disease without trying to exterminate it looks morally suspect.

And yet, in limiting the focus to eradication alone, we overlook the fact that we can prevent malaria deaths with drugs we already have. Instead of setting our sights on “eradication” of the disease, we should consider simply “reducing deaths” as an alternative goal — and work to redirect global funding toward that end.

Global health organizations, after all, can save many lives — though they would first have to accept a difficult fact: Malaria is not going away.

A version of this essay first appeared as part of a three-part series on global disease eradication efforts in De Correspondent, an in-depth, nonprofit digital news magazine based in Amsterdam.

Robert Fortner is an American science journalist who writes about world health care and the relationship between technology and science. His work appeared at HuffPost, Ars Technica, Scientific American, Columbia Journalism Review, and on his own blog. He is currently working on a book about Bill Gates.

Alex Park is an American journalist who writes about development cooperation. His work has previously appeared with, among others, Mother Jones, HuffPost, and Grist. He is currently working on a book about global soy production.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Perhaps click on WHO’s own Emergency Bulletin link (below) and look at Ethiopia, currently in the grips of a prolonged cholera outbreak but refusing to admit that it is cholera. Then realize that WHO is complicit in having it labelled, “Acute Watery Diarrhea” before holding up former Ethiopian Minister of Health, Ethiopian Minister of Foreign Affairs and current WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus as a paragon of healthcare advocacy.

http://newsletters.afro.who.int/outbreaks-weekly-bulletin/cny5fe95hahwgbw8szcdn9?email=true&a=11&p=53200937

Then perhaps write an article about the Ethiopian government fighting for years (now with an ally in charge of WHO) against one of the fundamental values of the International Health Regulations: transparent reporting.

Improving health systems in Africa is crucial, just as eradicating particular infectious diseases is necessary. The Western world has sustainable healthcare partly because they have fewer deadly infectious disease to deal with than African countries, for instance. If the UK, US or Canada was endemic for Malaria (plus other infectious diseases- combined) as most Sub-Saharan African countries are, I imagine they will have much less resources and personnel to commit to terminal diseases like Cancer.

The point is, eradicating some of the major deadly infectious diseases (like malaria, polio, TB, Yellow Fever, Ebola, Lassa fever, typhoid fever, cholera, tetanus, meningitis etc.) will free up resources and personnel towards building an even stronger health system.

Building strong health systems and eradicating deadly infectious disease are both crucial, but inseparable.

Almost half of the funds donated to support the Rotary International inspired Polio eradication effort are being used to shore up routine immunizations and child healthcare in the poorest and conflict involved countries. Those resources were also used to support the battle against the most recent Ebola outbreak. When Polio is eradicated more of those funds will be freed up to support other efforts. Terry Ziegler, Rotarian and Polio Eradication Newsletter Editor