When he reached into a bag that an assistant in Myanmar was holding out, Joe Slowinski had no idea he was courting his own oblivion. He thought a harmless wolf snake was in the bag, but it turned out to be a krait — a venomous jail-striped snake nearly a foot long. After the krait bit him, Slowinski, a herpetologist from the California Academy of Sciences, ate breakfast with his colleagues as though nothing had happened. People could barely detect any fang marks on his hand. But when a pins-and-needles feeling crept into his arm, he knew what likely lay ahead. He gathered his scientific team around him and informed them that his body systems would gradually start to fail. Despite team members’ attempts to revive him with CPR, he died the next day.

BOOK REVIEW — “Venom: The Secrets of Nature’s Deadliest Weapon,” by Ronald Jenner and Eivind Undheim (Smithsonian Books, 207 pages).

With just a subtle molecular nudge, as Slowinski well knew, venom can set off a near-irreversible cascade of bodily destruction. Every year, more than 100,000 people die after a snake bite, and slow-acting venoms can be as lethal as those that render victims twitching within minutes. But as devastating as they are, venoms are also essential in a broader sense. They ensure a healthy predator-prey balance in the wild, and some venoms can be harnessed to boost human health and well-being.

In “Venom: The Secrets of Nature’s Deadliest Weapon,” the biologists Ronald Jenner and Eivind Undheim sketch an overview of the venom universe that’s broad enough to account for all of these realities. Venoms may be as deadly as anything in nature, the writers argue, but they also promote life. In fact, venom molecules are just a hair’s breadth removed from organic molecules that most creatures need to survive. “The venomous animals responsible for causing human suffering,” they write, “represent only one small facet of the extraordinary diversity of the world of venom.”

That world encompasses far more than the destiny of any individual victim. Take two of the venomous predators people most fear, the Western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) and the king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah). Their very appearance seems sinister to humans, and for good reason. But on an ecological scale, rattlesnakes and cobras function somewhat like mouser cats — they keep quick-multiplying species at the base of the food chain in check. “Venomous predators help regulate the abundance and ecological impact of prey species,” the authors write. “Without snakes and spiders and other venomous predators, we might be overrun by roiling waves of rodents and suffocate in clouds of insects.”

Venom is also a crucial survival tool for animals that deploy it. For one thing, it endows small and physically weak species with self-defense and food-gathering skills rivaling those of much larger competitors. “It doesn’t take much,” the authors observe, “to imagine the alternative outcome of a plump soft-bodied animal armed with only small piercing mouthparts (spider) attacking a large insect with powerful spiny legs … without the assistance of venom.” Some species have evolved strategies to boost venom’s deadly effects even more. When the hunting spider, Cupiennius salei, injects its venom along with an enzyme called hyaluronidase, the venom packs twice the toxic punch it would on its own. The enzyme breaks down healthy tissue, allowing venom to spread faster through a victim’s body.

But prey animals aren’t taking their venom injections lying down. One of the most fascinating sections in the book details the evolutionary arms race between toxin-producing predators and their prey. The Northern Pacific rattlesnake, Crotalus oreganus, has long fed on ground squirrels that swarm across the Western U.S., but over time the squirrels have evolved resistance to a protein in the rattlesnake’s venom, improving their own survival odds. Similarly, the cute and unassuming grasshopper mouse eats fearsome bark scorpions for breakfast, thanks to its genetic strategy of blocking toxins in the scorpion’s venom.

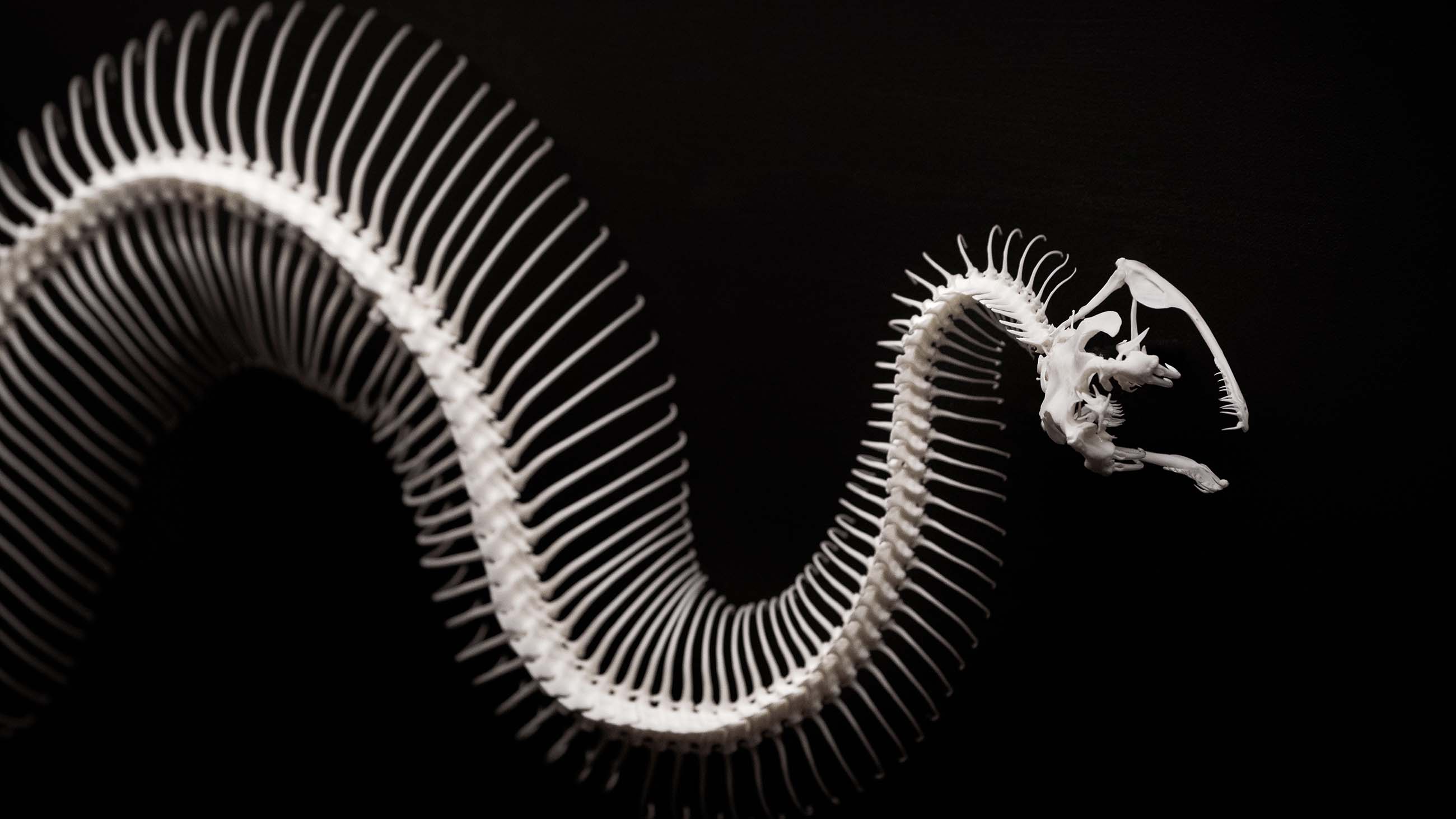

Still, on the whole, the ability to produce and deliver venom is so advantageous that it has evolved repeatedly within the animal kingdom — and just a few genetic tweaks can turn a nonvenomous species into a venomous one. Evolution, the authors note, “fashions bog-standard proteins into the most potent of toxins.” Many venom components are close cousins to enzymes that govern wound healing and cellular maintenance. Normally, these enzymes break down only certain types of unneeded tissue, but a slight molecular revision turns them into broad-spectrum tissue destroyers that make ideal venom ingredients.

That’s bad news for bite victims, of course, but it could ultimately bode well for some people with chronic health problems. In the book’s most hopeful passages, the authors describe how scientists are exploiting venoms’ unique properties to develop a range of human therapies. Two of AstraZeneca’s newest diabetes drugs, Bydureon and Byetta, were developed from a component in Gila monster venom that lowers victims’ blood sugar levels. And the anticlotting drug tirofiban (Aggrastat) — used to prevent heart attacks — comes from the saw-scaled viper’s venom, which makes victims bleed profusely to help the snake secure its prey.

For all its up-to-date detail, “Venom” is hardly the first book on nature’s toxic compounds, and it won’t be the last. It sometimes gets bogged down in technical nuance: While it usefully defines the difference between venom and poison (poison is passively secreted, while venom is delivered through mechanisms like fangs), it expounds on this distinction more than it needs to. But this book stands out for its evenhanded assessment of venom’s purpose within the community of life. It presents the story of venom as a vast circle, with the element of human suffering only one point on the curve.

As a poisonous snake expert, Joe Slowinski surely had some understanding of the fullness of that circle. But as he lay resigned to his fate, increasingly unable to move or breathe, that knowledge must have been cold comfort. Here, too, “Venom” gets the balance right, acknowledging that forces fueling a complex system can exact a severe price on the individuals within it.

Elizabeth Svoboda is a freelance writer based in San Jose, California.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Slowinski’s team must have been out in the “bush”. If you can get to a hospital with a respirator & antivenin soon enough, you can survive. I can’t imagine being out there in the middle of nowhere without at least taking antivenin injectable along …