A Growing Trend to Ban Solitary Confinement of U.S. Prisoners

The use of solitary confinement in prisons and jails in the United States has declined in recent years — a trend that gained added momentum this week when the King County Council, which governs Seattle, agreed 7-0 to ban the use of such punishments on local imprisoned youths ages 17 and under.

Seattle has joined a growing number of jurisdictions that are curbing the use of solitary confinement as punishment.

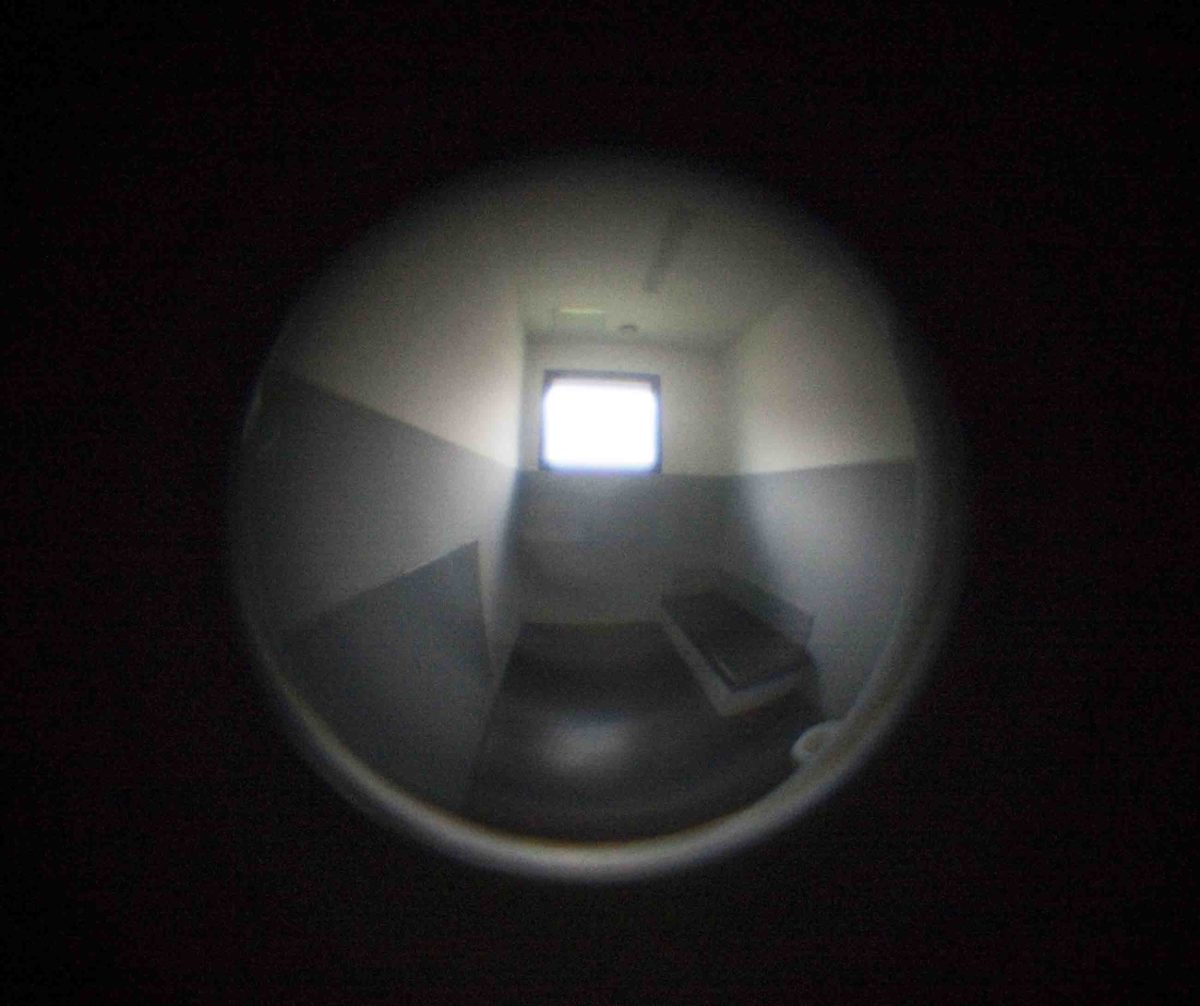

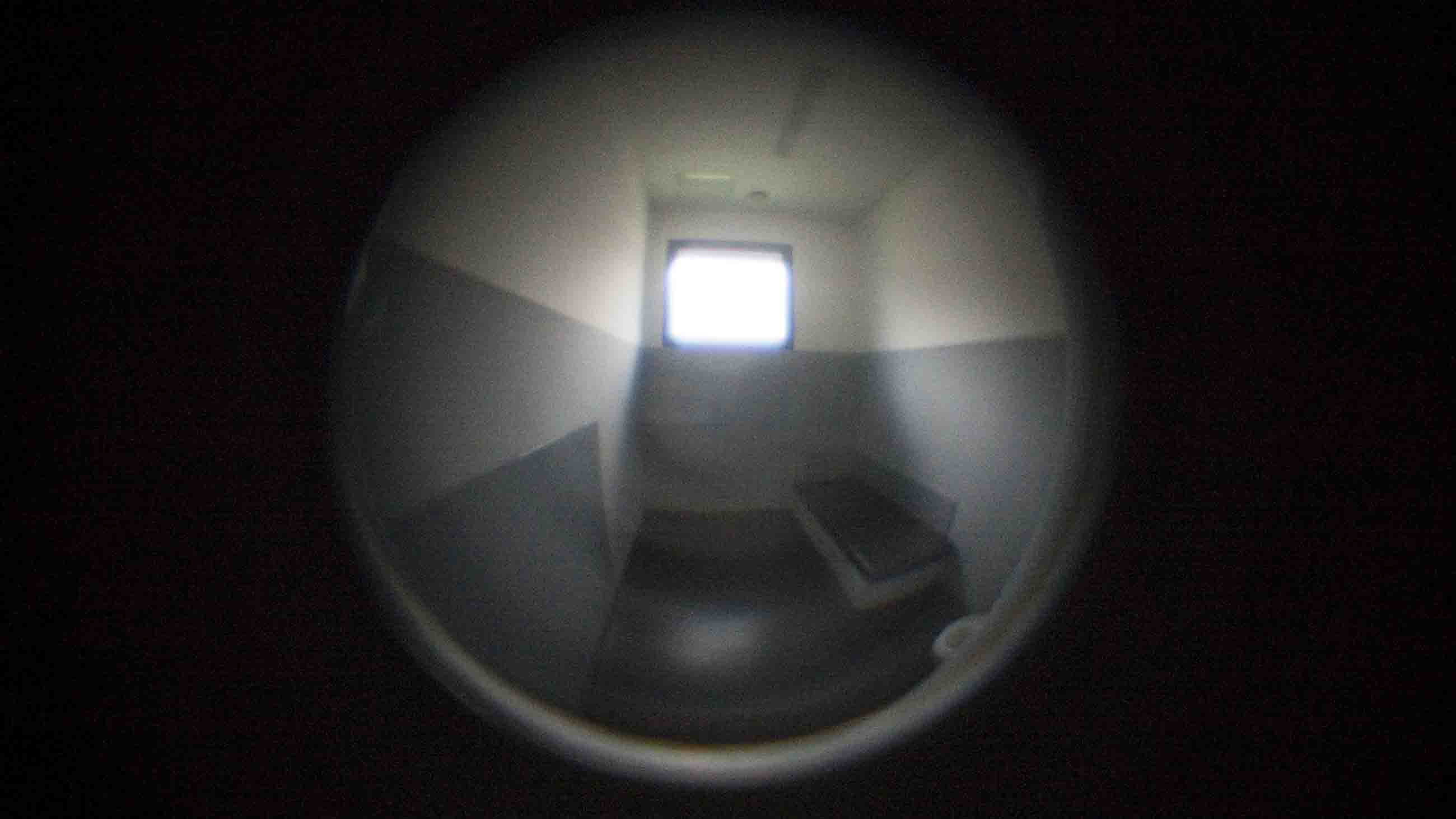

Visual: Thomas Imo/Photothek via Getty

Dozens of legal, mental health, and human rights organizations agree that solitary confinement should either not be used at all — especially on youths, pregnant women, and people with mental illness — or only as a last resort for periods of hours or days, not for the months and years that is typical. And many corrections professionals are getting on board. Rick Raemisch, executive director of Colorado’s Department of Corrections, wrote in October that the state was ending the use of solitary confinement lasting more than 15 days.

That time limit gained prominence in 2011, when the Special Rapporteur for the United Nations’ Human Rights Council released a report stating that confining prisoners in solitary beyond 15 days is “torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Colorado joins a handful of states, including Maine, California, Idaho, Illinois, and North Dakota, that have taken measures to close solitary confinement units or at least drastically reduce the numbers of prisoners in solitary in state detention, according to a draft of a review article published last month. The Federal Bureau of Prisons has also begun to put in place policies restricting the use of solitary and now bans its use on youths in federal detention, says the article’s author Craig Haney, a psychologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Solitary confinement involves separation from the general prison population and nearly total isolation from human contact in a cell that’s “the size of a parking spot,” as Raemisch wrote, where inmates are confined for 23 to 24 hours daily.

An estimated 80,000 to 100,000 imprisoned adults in the U.S. were held in some form of extreme isolation in 2014, according to a joint report by the Association of State Correctional Administrators and the Arthur Liman Public Interest Program at Yale Law School. The estimate does not include figures from jails and juvenile, military, or immigration detention centers. People of color, who are over-represented in the general prison population to start with, are more likely to be held in solitary than are white people, according to some reports.

A consensus on the severe mental and physical harms of social isolation in prison and beyond, based on dozens of studies, reports, and accounts across several decades and continents, is clear, Haney wrote in the review essay.

Prisoners in solitary are at high risk for emotional disturbances and breakdowns, stress-related reactions such as trembling and heart palpitations, crippling levels of anxiety and panic, memory and attention problems, and suicide among other symptoms and conditions.

In an essay published last year, President Obama called for an end to solitary confinement in federal facilities, adding to other criminal justice reforms made during his administration. The Trump administration has moved in the opposite direction, reinstating policies for strict mandatory minimum sentences and rescinding a curb on the use of private prisons.

But those changes only affect federal policy, Haney says, and he thinks it is possible that the trend to eliminate solitary confinement could withstand any Trump actions to reverse progress.

“So far, they have not taken explicit stands, at least that I am aware of, on the use of solitary confinement,” Haney says. “So, frankly, I’m not sure they’ve had any impact nationally, at least not yet.”

Inertia keeps the practice in place, Haney says, despite the lack of evidence for cost, prisoner rehabilitation, or prison management benefits. “When the scientific and human rights consensus changes, it’s hard for people who have been doing things one way — and thinking that way was ‘right’ for years on end — to change their thinking and behavior.”

It is difficult even for inmates to fathom the experience of solitary confinement, especially for long periods of time, as described by Earlonne Woods, co-host of the podcast “Ear Hustle.” He is in the general population at San Quentin State Prison in northern California, serving a 31-year to life sentence for attempted second-degree robbery, which included about a year in solitary at Pelican Bay State Prison early in his term. A July episode featured interviews with prisoners held in solitary even longer, including Armando Flores, who survived 26 years in solitary confinement.

“In my mind, I don’t know how they did it,” Woods said. “I mean, look at it this way. Think about all the things you did from 1989 to 2014. Now, imagine that most of those 26 years was in one room.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Banning solitary confinement is to little to late, everyone who suffered it and their families need compensation, a level of compensation that would put a huge dent in the corporations behind the judicial system and come out of their pockets.

The trend towards moving away from isolating people in prisons and jails is incredibly heartening. As Dr. Haney notes, this is an issue that sometimes leads to different perspectives among different groups of people. However, it has been so wonderful to see the number of people who have been willing to reconsider their positions and implement humane changes.

This is an issue that should elicit serious reflection among everyone, especially those advocating for changes. If people advocating for changes are not also seriously concerned and troubled about the possible negative outcomes of these kinds of changes, they are not seriously engaged with the issue. People can get seriously hurt and bad outcomes can occur, particularly in the early stages of implementing a new program. But in the long-term, treating people humanely is far likelier to lead to good outcomes than leaving people alone for months on end.

There was recently an article about a gentleman who was very seriously unwell and who gouged his eyes out while in custody. Without knowing the full circumstances of this situation, I think it is fair to say that everyone involved would wish it had gone another way. No human being should be so driven to despair, lack of reality or deprived of needed social supports that he should be moved to gouge out his own eyes. There is an opportunity to do better.

This is a tough issue and there are no villains in the larger solitary confinement discussion. I care about correctional staff and as a regular citizen who supports changes along with many others, I worry and reflect on the negative possible outcomes of humane changes. But cases like this one underscore the reality that sometimes situations are so bad that simply doing nothing about them in and of itself causes harm. Change can be hard, but sometimes things absolutely need to change. Figuring out how to change them takes teamwork, creativity, and learning from those who have already innovated and come up with different approaches. This is a very hopeful time and it is exciting to watch these good developments alongside the really tragic and heartbreaking stories.