Antifungal Resistance Is a Public Health Threat That Shouldn’t Be Ignored

In any given year, roughly two million U.S. residents contract an antibiotic-resistant infection — and 23,000 of those individuals die. This public health crisis will likely get worse, given the overuse of antibiotics in the cows and chickens that end up on our dinner tables.

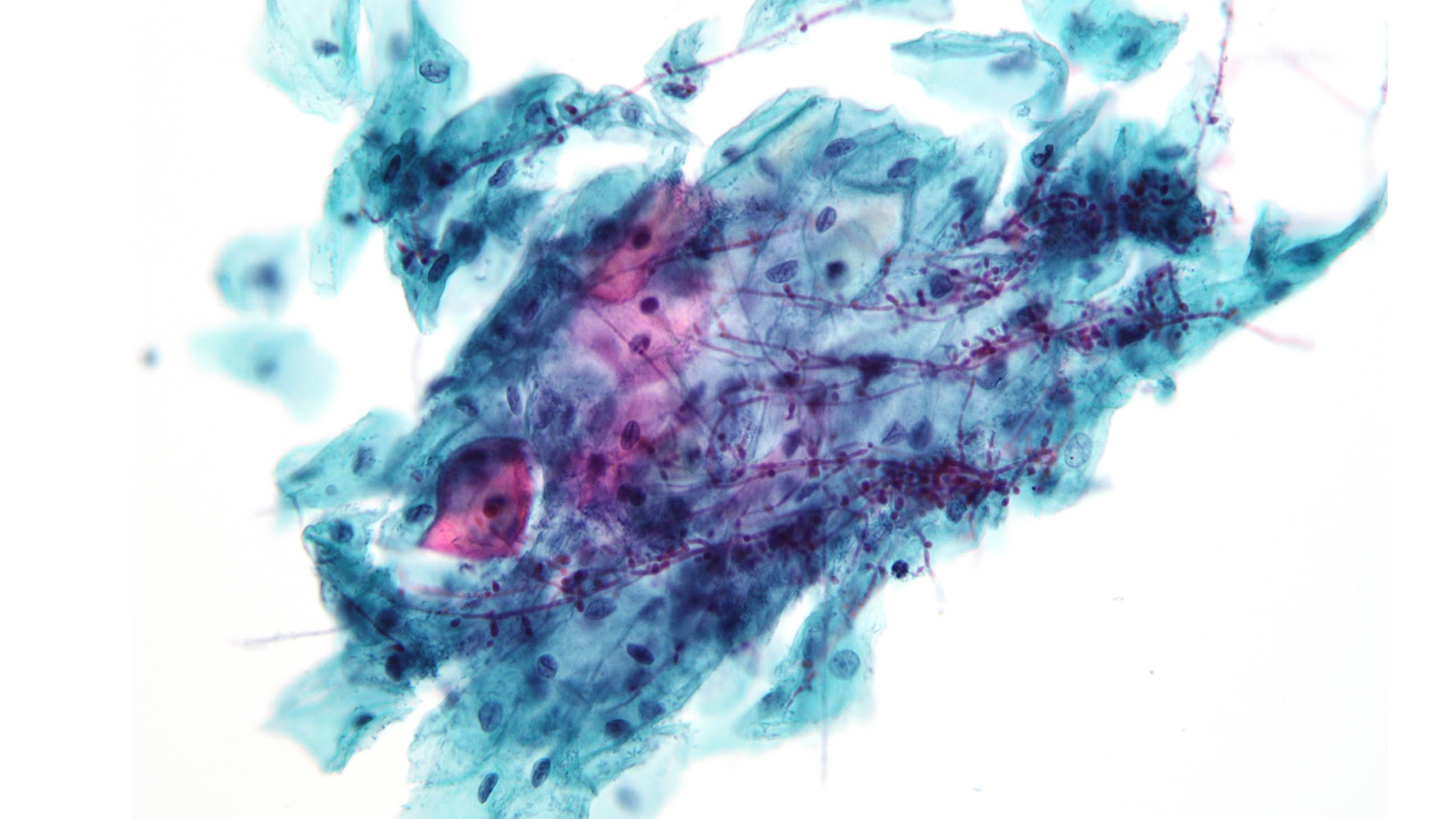

But antibiotic resistance is not the only looming public health threat in the world of infections. Antifungal resistance rightfully deserves its own spotlight — not least because fungal infections account for 25 percent of all infections that attack bodily surfaces. These aggravations might seem harmless, presenting as mere nuisances like unsightly rashes, nail discoloration, and itching. But like the bacterial infections being treated with increasingly less effective antibiotics, not all fungi are created equal.

Fungi are relatively picky and behave like bullies, often targeting people they perceive as weak and defenseless. People who are immunocompromised, or have weakened immune systems (e.g., people who have cancer or HIV, use biologics, have been taking corticosteroids for long periods, or are elderly —at a time when people over 80 are the fastest growing age group in the world) are at greater risk for fungal infections.

But just because fungi frequently profile people with weakened immune systems does not mean healthy human beings should underestimate their impacts.

Superbugs and superinfections — once the stuff of myth and science fiction — have now become conceivable realities. That’s true of both fungi and bacteria. Every class of antifungals — and antibiotics, for that matter — have now shown signs of resistance to known medications. And much like bacteria, as fungi become less responsive to standard pharmaceutical treatments, infections previously perceived as harmless may morph into something much more severe than a light rash or an annoying itch. A neglected superficial infection could prove deadly if it were to enter the bloodstream.

Such is the case with candidemia, the bloodborne version of the infamous Candida infections that drive vaginal yeast infections and thrush, a fungal infection in the mouth. Not only is candidemia harder to treat than its non-bloodborne alter ego, but its mortality rate is approximately 30 to 60 percent.

Or take Candida glabrata, a powerful cousin of the now-ubiquitous-but-less-threatening Candida albicans, which has shown strong resistance to treatment and is now the second or third most prevalent cause of candidemia worldwide.

The Candida family’s newest member, Candida auris, may be the most dangerous of all. First identified in Japan in 2009, some Candida auris infections have shown resistance to the three major classes of medications most commonly used to treat fungal infections, and in advanced cases often cause hearing loss. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently sounded its own alarm: Candida auris is a serious threat to global health that should not be ignored. What’s worse is that, while CDC researchers have documented outbreaks in hospitals and other health care settings, experts aren’t quite sure how this newcomer spreads. With the limited data available, scientists estimate that 30 to 60 percent of people who have been infected with Candida auris have died — but that’s not to say that many of its victims did not have other illnesses that may have hastened their deaths.

Nevertheless, not all fungi are evil. After all, mushrooms historically were and sometimes still are used in ethnobotanical medicine. Some, such as the Reishi mushroom, dubbed the “mushroom of immortality,” are enjoying newly found celebrity as “superfoods.” Other fungi, including Candida albicans, which live on the skin and the stomach’s mucosal linings, may enjoy a symbiotic relationship with health benefits. And if it weren’t for Alexander Fleming’s 1928 fungus-induced laboratory mishap, he may never have discovered penicillin, and the antibiotic industry may never have emerged. Millions of people would have succumbed to many infections in the decades after his discovery.

Still, while statistics on antifungal resistance remain scattered, we know this much: Fungal infections are on the rise and pose a serious threat to millions of people globally every year. Linked to everything from global warming to the overuse of antibiotics, which can make people more susceptible to fungal infections, they are surfacing at an alarming rate, and funding for research is not keeping up.

According to the Global Action Fund for Fungal Infections, the World Health Organization currently has no funded programs on fungal diseases, and there are fewer than 10 national programs monitoring their spread. Redirecting even a small percentage of the attention and funding that goes into antibiotic resistance could make a difference — and prevent a gathering threat from getting out of control.

Frieda Wiley is a freelance medical writer and clinical pharmacist who has written for AARP, Arthritis Today, U.S. News & World Report, American History (History Network), and iQ by Intel.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

There is a fascinating controversy that some (or maybe even most) of the most aggressive cancers exhibit many of the behaviors of fungi. The very concept of remission would seem to fit the studied behavior of the endospore — which would appear to have an ability to recede into a sort of protective cocoon and reemerge as a mutated lifeform (which can then colonize new forms of tissue).

I highly recommend as a supplement to this article (1) reading the Cancer as a Fungus controversy card which I’ve put together; and (2) then review the comments of that excerpt, where I have been tracking the debate over time. I have been very impressed by the explanatory powers of this hypothesis that the medical community has probably overlooked fungus as an actual cause for the spread of cancer.

Cancer as a Fungus

https://plus.google.com/+ChrisReeveOnlineScientificDiscourseIsBroken/posts/TJ45cMZTXJK

“Fungi are …..bullies, often targeting people they perceive as weak and defenseless.”

I guess we’d better boycott Nature!

Fungi serve an essential function in nature. They break down dead things so their organic materials may be used by new life. The closer you are to death, the more likely you are to be broken down by a fungus.

Are you suggesting that the only cure at the moment for Candida Auris is antibiotics? And, prevention would be…?

Hi Deborah- No, I am not suggesting that Candida auris be treated with antibiotics because antibiotics treat bacterial infections. Candida auris is a fungus and should, therefore, be treated with antifungals. I am saying that Candida auris is more difficult to treat because of its resistance to the antifungal medications most commonly used to treat fungal infections. Also, Candida auris is difficult to diagnose and frequently misdiagnosed, and this may contribute to resistance.

As for prevention: We know that Candida auris spreads from person-to-person contact and exposure to contaminated surfaces in healthcare settings. Infection control in healthcare settings appears to be the best method of prevention until researchers identify all the ways in which Candida auris infections spread. You can read more about that here: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/c-auris-infection-control.html.

Frieda, do you know of any research on the specific topic of candida having an ability to produce endospores, or any evidence of candida mutations within the human body?