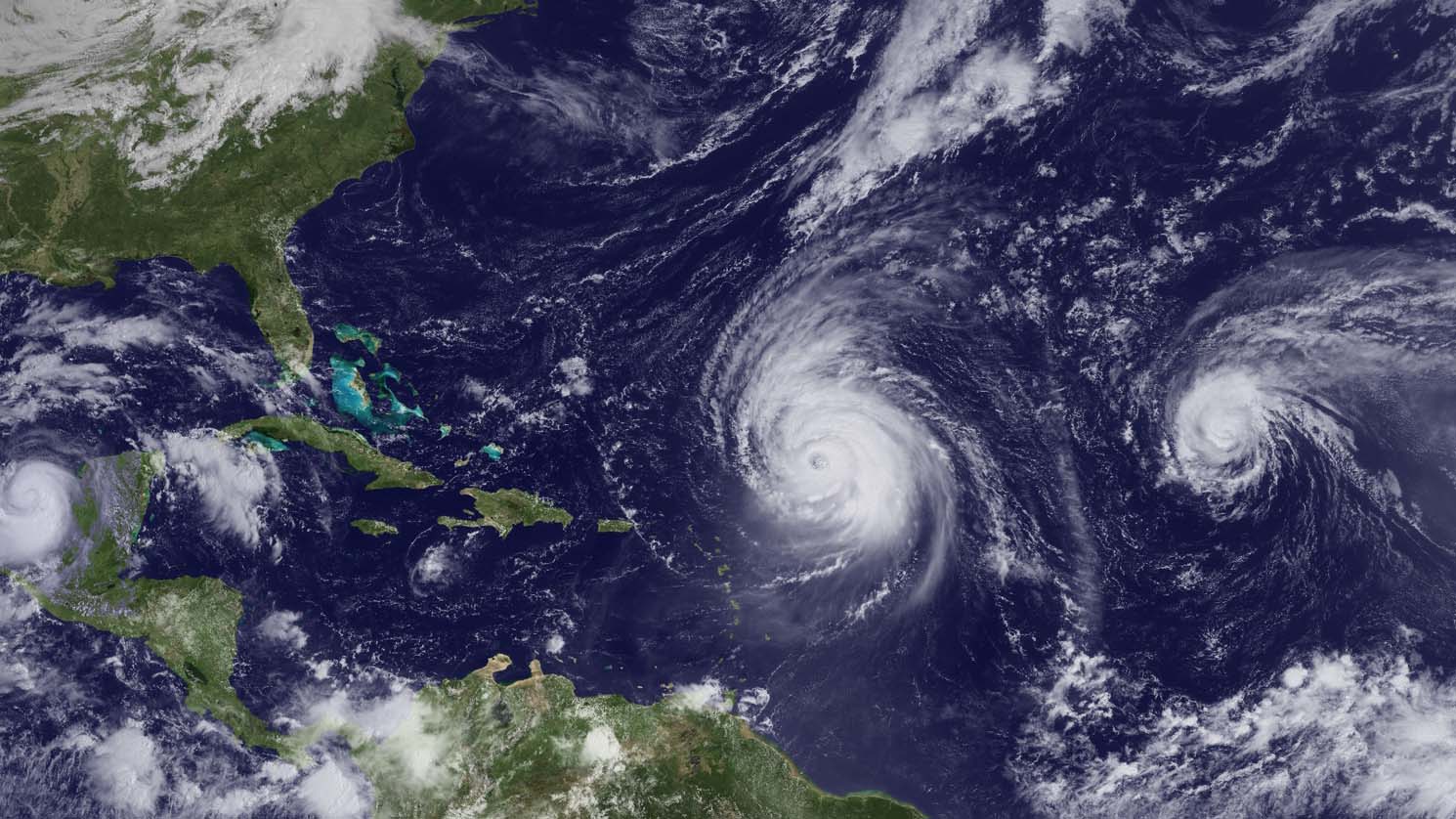

Throughout its history, Florida has regularly fought epic battles with water. One of the worst, the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926, left 372 dead and 43,000 homeless. This year, Hurricane Irma was the longest-lived major tropical storm ever recorded. It quieted from a severe Category 5 to a milder Category 3 by the time it struck Florida’s coast. Still, it destroyed one-fourth of the homes in the Keys, killed at least 75 Floridians, and filled the state’s coastal waters with millions of gallons of excrement, which poured out of failed sewage pump stations and overloaded treatment plants.

BOOK REVIEW — “The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities, and the Remaking of the Civilized World,” by Jeff Goodell (Little, Brown, 352 pages).

Some Floridians said such storms were nothing new. “We’ve rebuilt Miami before, and with the help of our communities and volunteers we will do it again,” a resident wrote in a blog for ABC News. President Trump traveled to the state in the hurricane’s aftermath, blithely handing out hoagie sandwiches in the Gulf Coast city of Naples, and proclaiming, “We’re doing a good job in Florida.”

But these days, the odds are increasingly stacked against Florida. Because of climate change, the seas are rising, storm surges are more severe, and eventually the state may be unable to hold its ground. A hurricane 20 years from now might be the unmaking of large parts of the coast.

At the heart of Jeff Goodell’s new book, “The Water Will Come,” is an account of Florida’s past, present, and future disasters, especially in Miami. The book also offers a wide-ranging narrative about the global crisis of sea level rise brought on by climate change. The opening serves up a bit of cli-fi (climate change-inspired dystopian science fiction), both nostalgic and macabre: “After the hurricane hit Miami in 2037,” it begins, “a foot of sand covered the famous bow-tie floor in the lobby of the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach. A dead manatee floated in the pool where Elvis had once swum.” And here he offers a warning: “This storm was the beginning of the end of Miami as a booming 21st-century city.” In real life, Miami may or may not be doomed, but it will never be the same. Nor will the rest of us, once the water comes.

The rest of the book is nonfiction — the real-life drama of climate change is breathtaking enough without fabrication — and Goodell brings it to life with near-encyclopedic reportage from all over the world. It’s a sobering topic to linger on for more than 300 pages, but the tone of the book is lively and personable. It reads partly like a travelogue and partly like a lesson from an exuberant science teacher. The first three chapters whirl through such topics as Florida’s geologic history, the scientific research that might explain the Biblical story of Noah’s Ark, an explanation of glacial melt in Antarctica, the reasons we have Ice Ages, and even a discussion of how water formed in the universe in the first place.

Having offered a crash course in these concepts, Goodell invites his readers to witness the ways that rising seas are lapping away at the edges of civilization. And he takes us to meet the experts, up close and personal. A contributing editor at Rolling Stone, Goodell has spent time with the world’s foremost scientists and political leaders. He interviewed former Vice President Al Gore, whose name has become synonymous with climate change advocacy. He accompanied the White House entourage when President Barack Obama visited Alaska in 2015 and interviewed him there, in the small Arctic town of Kotzebue. He joined then-Secretary of State John Kerry on a tour of the century-old Naval Station Norfolk, the world’s largest naval base, which may, in as little as two decades, be so flooded that it has to relocate. He met with Lowell Wood, the gadfly inventor and “dark star” of geoengineering, the field that is studying ways to redesign the entire globe in the face of climate change.

Encounters with these and other characters — the notorious, the celebrated, and the unknown — bring both authority and humanity to the book. Goodell also offers a tour of possible solutions to the challenges posed by rising waters, from the fanciful and clearly unfeasible to the pragmatic. We learn that the most technologically wondrous solutions are not always the best. Big, costly engineering projects — such as the nearly complete floating barrier of Venice, Italy, or the giant berm that New York City has considered building — are often controversial and can be plagued with cost overruns. Moreover, any such solution may fail if it miscalculates the severity of sea level rise: A wall designed to hold back six feet of water is useless if the oceans swell by eight feet.

In a similar vein, seemingly magical solutions — like a Nigerian floating school designed by an award-winning architect — are sometimes too good to be true. (The school collapses in a storm just before Goodell heads to Nigeria to see it.) Meanwhile, simple innovation is sometimes most effective. Goodell meets with slum dwellers in Lagos, Nigeria, and marvels at their resourcefulness: They have learned to build houses that can quickly be raised if floods become a problem.

Between these journeys, Goodell returns, again and again, to Miami, the “New Atlantis,” as he calls it — a metropolis reclaimed from wetlands and built on fantasies of beach life and real estate speculation, a city that may or may not be lost. Already, some of the chronic problems posed by flooding and sea level rise in Miami are nearly as disturbing as the acute impacts of storms like Irma. For instance, septic tanks are leaching into waterways. Storm drain outfalls in parts of the city already have fecal bacteria levels more than 600 times what state regulations allow.

And the response of local government and business leaders sometimes alternates between outright denial and magical thinking. Scott Robins, the owner and manager of prominent properties in downtown Miami and Miami Beach’s Art Deco District, tells Goodell, “We’re going to raise the city two feet,” without any indication of how this is feasible. When Goodell asks Jorge Pérez, a wealthy Miami developer, how his properties will handle rising seas, Perez replies, without remorse, “By that time, I’ll be dead, so what does it matter?”

There are no silver bullets in this book, no obvious happy endings. But its message isn’t hopeless — rather a warning against folly. Miami was built on a dream, but we are not living in one. It’s pointless to pretend that we can rely on the brash optimism and hubris of the past to insulate us from the floods of the future. The water is rising, and things will get ugly, filthy, and dangerous if we ignore what’s coming. Hoagies and cheerful platitudes will not save us. But the realism and honesty of a book like this might help us confront the seriousness and urgency of the problem that is creeping up right at our feet.

Madeline Ostrander is a freelance science journalist based in Seattle. Her article on climate change and the national parks appeared in Undark in September. She has also written for The New Yorker, Audubon, and The Nation, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Magical “failures”, like a floating school in Nigeria come from architects and similar types, very seldom from engineers. It might be a good idea to keep this in mind when asking “everyone” to help solve the problems of climate change.

Florida was enormosly diminished by 120 meter (394 feet) sea level rise post-glaciation. “The water is rising” is not even decimal trim, at most a few inches.

Six feet is built in in the lifetime of a child born today.

Miami is finished.