First Blood: Fixing American Trauma Care

Frank Guyette was a 17-year-old volunteer emergency medical technician when he responded to one of his first bleeders — a young woman in a car crash with a severe head wound. She was unconscious in the driver’s seat, and there were hazards everywhere: traffic zipping by, broken glass, gasoline pooling on the pavement. From the passenger side, Guyette did what he had been trained to do: apply bandages and pressure, elevate the wound, and find pressure points on arteries to cut off the bleeding.

None of that proved very effective.

“When you get to the scene of a car accident, it’s overwhelming,” said Guyette, now 43 and an associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. The woman would eventually recover, but in Guyette’s early days as an EMT, he would find himself in this hapless situation again and again with hemorrhaging patients: Holding a bandage to a wound until the ambulance could deliver a patient to a hospital. In almost all cases, Guyette and his paramedics simply couldn’t stop the bleeding, in large part because the standard protocol for first-responders encountering a bleeding patient 20 years ago just didn’t work that well, he said.

Two decades later, though, very little has changed. “It’s pretty sad how poorly equipped the country is to deal with severe hemorrhage,” said Andrew Cap, chief of blood research at the U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research. “The infrastructure is just not there.”

That’s a major concern in the United States, where the toll of trauma — including this week’s tragic shooting attack in Las Vegas, which claimed at least 59 lives and left hundreds bleeding on the ground — is heavy. Americans drive fast, shoot guns, work in environments with little oversight, and often live in isolated corners of a vast country with limited emergency services. Indeed, the number-one killer of Americans aged 46 and under is trauma, either by fall, car accident, or gunshot — and this does not include hemorrhaging deaths in operating rooms during childbirth or surgery.

Based on 20 years of military research, there are two key factors that save trauma victims: staunching the wound and replacing the lost blood — quickly. But today, some ambulances still don’t carry the right tools to stop bleeding fast — things like tourniquets and mineral-infused combat gauze. And unless a hemorrhaging trauma victim is lucky enough to get whisked away by an air ambulance, they’re unlikely to receive a blood transfusion until they arrive at a hospital.

But many of those victims will die needlessly before they ever get there, critics say — a senseless body count that could be prevented if the nation’s civilian trauma care system modeled its emergency response after the military. According to a report on trauma deaths from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, updating the American trauma system could save 30,000 people a year. To do so means overhauling how citizens and medical providers respond to trauma, as well as how they collect and store blood.

Change is beginning to take hold in Pittsburgh and a handful of other cities, which are looking to the battlefield for solutions. From supplying first responders with tourniquets and in-field blood supplies, to educating the public on how to treat a trauma victim, hemorrhaging can be treated swiftly, properly, and at the site of an accident, rather than waiting for hospital personnel to step in.

If Guyette had treated the woman with the head-wound today, he says he would start by applying a special dressing that can stop the bleeding within minutes. That’s just one of the “huge changes,” that he has seen the past decade.

But for proponents of these protocols, the challenge will be to get those changes to take hold nationwide.

While forward-thinking hospitals like the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) have made vast improvements recently, the military has been constantly improving how it responds to trauma for more than 20 years. Lesson number one from the battlefield: Stop the bleeding fast. The sooner someone can close up a wound, the better the chances for survival. In some cases, like when a person is shot in the femoral artery that runs along the thigh, their survival time may only be five to 10 minutes, said Frank Butler, a retired military surgeon. That is, unless they get a tourniquet.

Most people have probably seen tourniquets in action movies where the hero grits his teeth and wraps a belt around a bloody arm or leg. Even that primitive version of the tool would have come in handy for Guyette in his early days of being an EMT. But at the time, tourniquet use was considered dangerous.

When Butler started evaluating combat care procedures in 1992, “nobody in either the military or civilian sector thought it was a good idea to put on a tourniquet.”

That’s because during Vietnam and other past wars, tourniquets were used incorrectly and kept on for a day or days, leading to nerve damage and amputations. But even though the military and civilian trauma care system shied away from them, when Butler started looking into the practice, he realized surgeons had been using tourniquets all along. “If you’re an old college basketball player like me, and you’ve had knee surgery, the orthopedic surgeons at the start of the procedure will put a tourniquet on the leg,” he said.

In the 1990s, once Butler and other military trauma doctors realized they had misjudged tourniquets, they started to question what else they were getting wrong. Over 20 years, they developed procedures to improve trauma response and save lives, called “Tactical Combat Casualty Care.”

Tourniquet visuals via Science Museum, London, Wellcome Images/CC

The first step was to build a better tourniquet, since the old ones hadn’t really been updated since the Civil War, said Russ Kotwal, Director of Strategic Projects for the Department of Defense Joint Trauma System. These older tourniquets were basically a strap and buckle, both ineffective and difficult for a person to apply to their own arm or leg. The tourniquet has to be tight — often painfully tight — to stop blood flow, and yanking a strap has its limits. The military designed easier-to-use tourniquets that, for instance, incorporate a ratchet or pump. A person can pump or turn the device tight using one hand. Today, the new tourniquets are ubiquitous throughout the military, said Kotwal.

The improvements work. Take the 75th Ranger Regiment, trained in Tactical Combat Casualty Care so that all rangers — not just medics, as is typical — were equipped with tourniquets to treat hemorrhage in the field. When Kotwal analyzed this regiment’s combat data from 2001 to 2010, he didn’t find a single preventable death. And, compared to the military as a whole, the regiment’s rates of soldiers killed in action were about 5 percent lower.

Despite the success, the changes to trauma care have been slow to hit the civilian sector. In a paper published in the journal Surgery in 2015, researchers surveyed the adoption of battlefield innovations by civilian trauma care centers. Only 40 percent of the trauma centers responded. More than half of those respondents reported that less than a fifth of patients who could benefit from a tourniquet arrived at the hospital with one.

The military developed other blood-stopping technology, too, including better wound dressings, coated with mineral powder, which lets liquid soak through but traps natural blood-clotting elements to help quickly close wounds. But use of this clotting gauze was even less common. For example, the researchers from the Surgery study found that only 7 percent of the responding trauma centers used those types of dressings.

Butler, who is chairman of the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care for the Department of Defense, expects those numbers have changed for the better recently — but there is plenty of room for improvement. The evidence is out there for everybody to see, “but not everybody acts on it,” he said.

But after decades of delay, change may soon be coming to our civilian trauma centers. A preview of that can be found in Pittsburgh.

Taking their cue from tactical combat casualty care guidelines, Pittsburgh emergency care responders are not only focused on stopping the bleeding, but also getting the lost blood back in. UPMC has been using whole blood for the resuscitation of trauma patients since 2014, making it one of the first trauma centers in the country to do so, said Mark Yazer, a pathologist at the hospital.

The vast majority of trauma centers do not use whole blood in emergencies, and they haven’t done so for decades. Ground ambulances aren’t equipped to give transfusions in the field because, in most cases, only doctors or nurses are allowed to provide that service. In Pittsburgh, a doctor on call will respond to an accident if needed, but she too would have to make do with the only blood available, which is typically split into separate bags by its key components: red cells, which carry oxygen through the body; platelets, which induce clots; and plasma, the liquid that holds the other cells and which also helps with clotting.

In some cases, this may mean infusing the patient with a single blood component and hoping that works. Or, in the middle of a chaotic trauma scene, doctors may have to juggle three separate bags of blood in order to get all the components back into the patient in equal ratios. Here, they’re essentially putting whole blood back together again.

The reason our medical system uses blood components instead of whole blood has to do with how those component parts are stored. Both red cells and plasma are best in the cold, but platelets need to be at room temperature and only last five days. Since red cells last up to six weeks in the cold, doctors can get more use out of them if separated from platelets. Similarly, frozen plasma can last months and, once thawed, another five days.

Up until the 1970s, type O whole blood, which can be used as a donor for all blood types, was generally given to people in emergencies. But in that previous decade, scientists determined that platelets stored at room temperature circulated longer in the blood than cold platelets. This was considered especially useful to leukemia patients because their suppressed bone marrow wouldn’t produce as many platelets.

But an infusion of cold platelets could be cleared from circulation far sooner than platelets stored in room temperature.

“When you put platelets in cold temperature, they sort of clump together” and don’t like to un-clump, said Erica Wood, head of the Transfusion Research Unit within the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at Monash University in Australia.

But the problem with this line of thinking is it assumes the greater number of platelets circulating, the better it functions at its job. “That doesn’t really make sense,” said Andrew Cap, the military surgeon and transfusion specialist who studies cold platelets. Cap’s research suggests that cold platelets actually function better than room temperature platelets. Cold platelets are less prone to bacterial infection and could be stored for 12 to 15 days. He hasn’t had a chance to test this out on people, but we have seen that use of whole blood — which contains cold platelets — works.

During the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, American military surgeons questioned the policy of using blood components — and in particular, room temperature platelets. Cold whole blood can be stored up to 21 days and it’s also easier and faster to collect since it doesn’t require pulling out individual blood components. Since they could be low on platelets in the field, military surgeons started using whole blood instead. They found the practice was just as effective as platelets alone in treating wounded soldiers. But bringing whole blood to our civilian sector turns out to be far more complicated.

One reason Pittsburgh is one of the first places to test whole blood is that Yazer is a member of the Trauma Hemostasis and Oxygenation Research (THOR) Network, an international network of health care professionals trying to improve trauma response using military protocol. While most hospitals give trauma patients blood components, UPMC gives them whole blood as soon as they arrive.

“Really, whole blood should be used in the field,” said Yazer. If the patient needs red cells at the scene of the accident, then whole blood’s going to be the right product for them, he added. “It’s easy to transport, it’s more concentrated than component therapy, and it facilitates the logistics of resuscitation much better.”

UPMC also works with a private blood bank that has been proactive in changing its protocols based on doctors’ needs, said Guyette. Without that, they wouldn’t have access to whole blood.

The largest supplier of blood products, the American Red Cross, does not offer whole blood.

Dr. Phil Spinella, a pediatric critical care doctor at Washington University in St. Louis, owns an antique blood transfusion kit from the 1920s. Prior to the latter part of the 20th century, whole blood was used for blood transfusion, a practice Spinella believes should return.

Visual: Leah Shaffer for Undark

“The smaller blood suppliers are starting to be more willing to provide whole blood, but the big boys and girls on the block have not come around yet,” said Philip Spinella, a pediatric critical care doctor at Washington University in St. Louis, who helped develop the THOR network.

In an email statement, a Red Cross media representative said that its biomedical team is still evaluating whole blood.

Spinella is such a proponent of whole blood because it could easily help solve supply issues in smaller hospitals and he believes whole blood transfusions to be the most effective response to traumatic blood loss. As it stands now, many places don’t even keep platelets because they will expire before use, said Spinella. “Whole blood allows you to give all the necessary components to a bleeding patient efficiently and probably more effectively because you would be storing the whole blood cold,” said Spinella.

He’s frustrated with the larger blood suppliers because they won’t provide whole blood. For the system to really change, “the lynchpin here are the blood suppliers.”

Even if whole blood was made available to ground ambulances, they’d have to change how emergency medical systems are funded. “Reimbursement laws for EMS systems are incredibly inadequate,” Spinella said. In general, EMS care is reimbursed not by the service they provide, but more of a one-time fee for getting a person to the hospital.

“It’s your ambulance ride, no matter what happens on the ambulance,” he added. There’s no incentive for ambulance systems to record what they do and to bring more expensive equipment and therapies into the field.

It also costs money to set up blood banks and reorganize them. Just carrying red cells is a substantial investment — $10,000 per helicopter base, according to Christina Ward, corporate communications director for Air Methods, a flight rescue operation with bases around the country. Air Methods has about 50 bases set up to deliver red cells, which they have been doing since 2016.

While setting up whole blood programs takes coordination and money, it is possible. So far, such programs are underway in San Antonio, Houston, the Mayo Clinic, Rutgers University-Camden in New Jersey, and Intermountain Healthcare in Utah, according to Spinella.

Pittsburgh is running a multicenter trial of randomized patients who will receive plasma in the field in addition to red cells. UPMC is also in the early stages of setting up a study to test whole blood in the field, said Yazer.

In Pittsburgh’s trauma center, doctors have treated approximately 170 trauma patients with whole blood, but the next step is to compare those who get whole blood to those who receive component therapy, said Yazer. So far, they’ve seen there is no harm in patients receiving whole blood. “But we haven’t had enough patients yet to say that there’s a benefit to it,” he said.

Yazer also emphasized there is still a place for component therapy. Once the patient stabilizes, they might need certain blood components more than others — for instance more platelets to help with clotting.

The goal, Yazer added, is to allow doctors to “start tailoring the care to what a patient actually needs.”

On April 9, 2014, a 16-year-old student at Franklin Regional High School slashed his way through the hallways, stabbing 21 students and a school police officer before being subdued by an assistant principal. The school is located just outside of Pittsburgh and police and emergency responders got there quickly, but most importantly, brought tourniquets and clotting gauze. Witnesses described seeing students and teachers applying pressure to wounds. Everyone survived.

“Some of those kids are alive because of that early aggressive hemorrhage control,” said Guyette.

The tourniquets and dressings at Franklin are a simple step but they make the biggest difference, and Pittsburgh is leading the way for training not just with emergency responders, but also with the public. In addition to police and firefighters, staff at school districts in Pittsburgh are getting trained in hemorrhage control, according to Lenworth Jacobs, vice president of academic affairs at Hartford Hospital in Connecticut and chairman of the Hartford Consensus, a meeting organized by the American College of Surgeons that kicked off the civilian program to improve bleeding control.

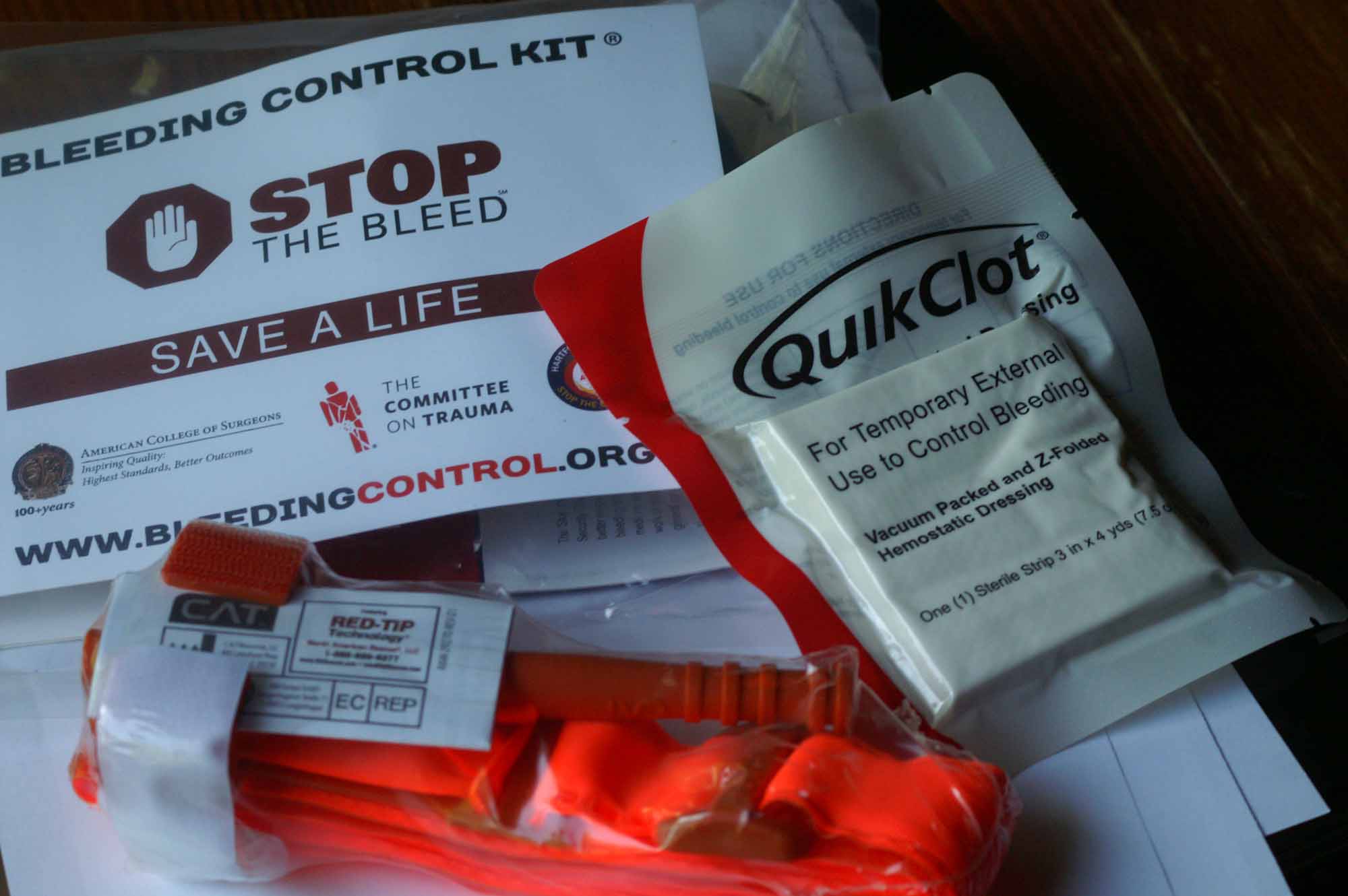

In 2013, Jacobs and colleagues launched the first Hartford Consensus Conference in response to mass attacks such as the Boston Marathon bombing. Attendees included military, EMS, police, and doctors to talk about how to improve survival of trauma victims. A program that emerged from this meeting was the Stop the Bleeding Coalition, a nonprofit that advocates for early intervention in cases of severe bleeding. Pittsburgh is one of the cities where officials are embracing this campaign.

The coalition’s first step was to improve how police respond to trauma. Cops are often the first on a trauma scene, and in the past, they weren’t trained or required to control bleeding.

“First order of business was to modify that mission,” said Jacobs. Using the tactical combat casualty care guidelines and working with the Major Cities Chiefs Association, members of the Hartford Consensus developed a program to train officers in bleeding control. More than 300,000 law enforcement officers across the country went through that training, he said. These officers now keep bleeding control kits in their cruisers that include clotting dressing and tourniquets.

While training in bleeding control started out as way to help society be more resilient to mass attacks, the same lessons apply to everyday accidents.

“There’s motor vehicle crashes, there’s industrial accidents, there mishaps in the home—all those things will always continue to happen,” said Matt Levy, Stop the Bleeding Coalition chair. “And when they do, this knowledge is equally as important.”

Bleeding control kits are still not ubiquitous among all emergency responders, including EMS and fire rescue, but it’s quickly improving. “More and more EMS operations, fire services are carrying this type of equipment,” Levy said. “It is becoming the standard of care.”

One of the Stop the Bleeding Coalition’s ultimate goals is to help the public respond to traumatic bleeding as quickly as they do when someone has a heart attack. In that type of an emergency, a bystander would probably do CPR, said Jacobs, or turn to the nearest automatic external defibrillators — machines that use an electric pulse to restore heartbeat and are found in many public buildings. The Stop the Bleeding Coalition hopes to get bleeding control kits right next to those AEDs, so that anyone can help a trauma victim.

“Society empowers its citizen to become involved,” Jacobs said. “And we want that process to be going on in hemorrhage.”

In the past few years, since the start of Pittsburgh’s move to pull military trauma practices into the broader emergency system, the city’s trauma response has transformed. Adding clotting dressings and tourniquets to first responders’ toolkit have “truly been life saver,” Guyette said.

“We had a young man working in his dad’s workshop with a circular saw— nearly took off his arm,” he added. “That’s where the tourniquet made a difference.”

The bleeding control kits are now in schools, too, something that could have made a huge different 20 years ago, when Guyette was a teenage EMT. Coming back from track practice one day, he spotted an elderly woman on the ground bleeding. She had slipped and opened a large vein that runs down the leg. Guyette ran to the office and grabbed a first aid kit. While they waited for the ambulance, he elevated her leg and applied pressure. It was very difficult, and he couldn’t get control of the bleeding.

“Those things weren’t terribly effective and today, that never would have happened because the first thing we would have done was put a tourniquet above the bleeding and stop the bleeding.”

Pittsburgh researchers hope to soon start giving full blood in the field, to see if that too can be even more effective at saving lives.

“Even though blood therapy is logistically difficult, it makes sense,” said Guyette. “That’s what the patient lost. You should give it back.”

Leah Shaffer is a freelance science writer based in St. Louis. Her work has been published by Science, Discover, Wired, and the St. Louis Post Dispatch, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I’m impressed, I must say. Seldom do I encounter a blog that’s both equally educative and amusing, and without a doubt, you

have hit the nail on the head. The issue is something which not

enough folks are speaking intelligently about. I’m very happy I found this

in my hunt forr something concerning this.

I think one of the hardest transitions between what really works to save lives, proven in the combat environment, to transfer into the civilian environment is the legal issues. In combat, service men and women are equally trained and know the risks and if something that saved their life was applied and they suffered necrosis of the tissues as a result, they don’t sue. They are grateful to be alive. In the civilian world ignorance is bliss and even though you saved someones life, if they have a disfigurement or disability because of it you are going to be sued. Malpractice is a lawyers whipped cream. I’m saddened that we can’t save lives because too many people have lawsuit in the back of their minds.

Cypress Creek EMS and ESD 48 Fire Department in Harris County/Houston, Texas are now carrying WHOLE BLOOD in the field 24/7/365. We are partners in the same program with the Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center. In addition, the CCEMS Tactical Medic Team has been teaching bleeding control (B-Con) to police, firefighters, and EMS personnel for many years and is now the only such team in the nation that carries whole blood during missions and training exercises. We’ve also trained hundreds of school nurses and school personnel. This year, we began training the public under the national Stop The Bleed Program. This is the best article I’ve seen on the importance of B-Con training and transfusing Whole Blood in the Field. It explains exactly why we are doing what we are doing. Bravo. We are sharing this via our social media.

as with quick clot that you used to poor into the wound and caused even more problems , like getting it out . How would you clean all these tiny sponges out and what type of damage may they cause while in the wound?

It is actually a misnomer to call them “tiny sponges”. Before they encounter a wet substance they are a large pellet (bigger than an 800mg ibuprofen). When they encounter that wet substance they expand a fairly significant amount which is what stops the bleeding. They are also marked with a radiopaque “x” so it is easy to identify if there are any left in the wound when they are being removed in the operating room. This website has great pictures that illustrate the actual size: https://newatlas.com/xstat-combat-injury-treatment-injectable-sponges/30710/#gallery

Many innovations are working their way from the battlefield to the streets. RevMedx in Oregon worked with the Army to invent a syringe that is placed into the gunshot wound which injects tiny expanding sponges that quickly stop bleeding. They also sell a tourniquet that is worn as a daily wear belt which allows everyone to be prepared at a moments notice when bad things happen.