In 2009, a group of Spanish scientists announced they had briefly resurrected a Pyrenean ibex, a kind of mountain goat that had been extinct for nearly a decade, in the womb of a surrogate animal. More recently, the Harvard University geneticist George Church has taken steps to splice mammoth genes into Asian elephant DNA, in the hopes of one day creating new mammoths in artificial wombs. And on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, the lowly heath hen, which officially went extinct in the early 20th century, might soon experience a genetic second-coming itself.

WHAT I LEFT OUT is a recurring feature in which book authors are invited to share anecdotes and narratives that, for whatever reason, did not make it into their final manuscripts. In this installment, author M.R. O’Connor shares a story that didn’t make it into her latest book “Resurrection Science: Conservation, De-Extinction and the Precarious Future of Wild Things.”

Not everyone thinks all of this resurrection is a good idea, of course, and recent scientific advances in cloning, genetic engineering, in-vitro fertilization, and captive breeding are driving a roiling debate over de-extinction — from its potential for unintended ecological consequences, to its power to distract from the more immediate perils facing species that are still with us.

A less frequent criticism: De-extinction is a Nazi-era concept.

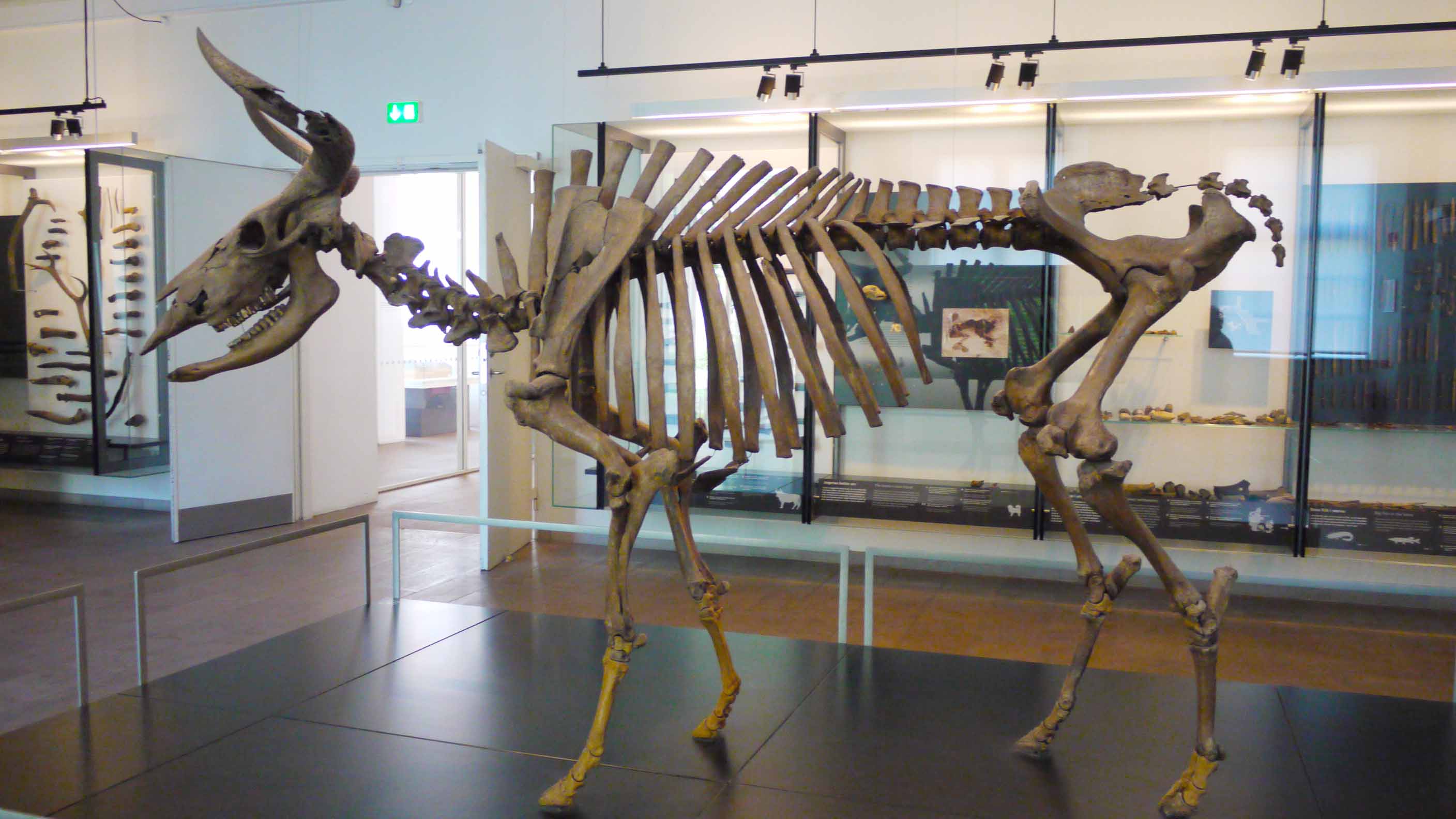

If that sounds preposterous, consider that the roots of our current fascination with de-extinction science can be traced at least as far back as the 1920s — and specifically to early Nazi Germany, where scientists produced what was arguably the world’s first example of such magic: the aurochs.

This muscular, wild, and aggressive European breed of cattle was the ancestor of domestic cattle, and by the 17th century, it had vanished due to overhunting. But by the early 20th century, German culture, including its scientific community, was awash in explorations of Darwinism, death, and nature — ideas that would fester into preoccupations with racial purity, survival, and geography. As natural science and National Socialism began to intertwine, resurrecting the undomesticated, unruly aurochs — a sinnbild der Urkraft, or “symbol of primal force,” and an example of the primordial wildlife that embodied true Germanic ideals — became a measure of Nazism’s power itself.

The geographers Clemens Driessen and Jamie Lorimer document this history in a chapter of the book “Hitler’s Geographies,” published last year. As they explain, at the center of these efforts were two brothers, Lutz and Heinz Heck, directors of esteemed zoos, in Berlin and Munich respectively.

The brothers were interested in the possibility of resurrecting the aurochs through back-breeding — essentially recreating an extinct phenotype through selective breeding — and they traveled the continent searching for suitable domestic species carrying the aurochs’ key traits and genetic lineage, from Spanish fighting bulls, Hungarian steppe and Scottish Highland cattle, to Holsteins and Alpine breeds. Lutz in particular came to view de-extinction of the aurochs as crucial to National Socialism and the Nazi party’s ideology. He also saw it as integral to recreating the mythical German landscape of ancient times, when the Aryan race was pure and unthreatened.

“The reshaping of this dull and strange landscape into a German one must be our most important goal,” Lutz wrote. “For the first time in history the imprinting of a cultural landscape will be consciously taken up by a people.”

By 1937, Lutz had joined the SS and the Nazi party, which began to support his de-extinction efforts. Later, both Heinz and Lutz joined Heinrich Himmler’s scientific research organization, called Ahnenerbe, which was dedicated to the study of the Aryan people. Driessen and Lorimer detail how Lutz began calling for the transformation of newly conquered lands in the east in order to recreate the primordial forest described in the epic Germanic poem “Nibelungenlied.” Lutz and Hermann Goering, founder of the Gestapo and president of the Reichstag, became friends and went hunting in traditional dress and armed with spears to try and recreate the heroism of ancient German mythology. When Lutz released his back-bred aurochs into a reserve in 1938, he wrote that, “the extinct Auerochs has arisen again as a German wild species in the Third Reich.”

In Driessen and Lorimer’s view, the aurochs project gave Nazi notions of racial purity a spatial dimension “in which the right environment, achieved through landscape conservation and design, is just as important for [German society] as racial hygiene aimed at purging the heredity base.”

Lutz’s aurochs mostly died in the bombing of Berlin at the end of the war, but his brother’s examples in Munich survived, and the siblings’ efforts have been carried into the present under the guise of a much different endeavor known as rewilding — or the recreation of extinct wild landscapes. Aurochs-like descendants of “Heck cattle” are now present in rewilding preserves in Spain, Croatia, Portugal and the Netherlands. Other rewilding projects have been proposed in North America and the Middle East, as well as Russia, where future mammoths, resurrected from extinction, might one day roam.

Contemporary de-extinction advocates often present resurrection of extinct animals as a conservation strategy. George Church of Harvard has gone so far as to suggest, in an interview with New Scientist magazine, that reanimated mammoths could help combat global warming. “They keep the tundra from thawing,” he was quoted as saying, “by punching through snow and allowing cold air to come in.”

But the conservation biology community itself remains highly skeptical of such arguments. In March, six biologists published a cost-benefit study in the journal Nature: Ecology & Evolution that argued de-extinction could produce highly negative consequences for existing species. “If conservation funds are re-directed from extant to resurrected species, there is a risk of perverse outcomes whereby net biodiversity might decrease as a result of de-extinction,” the authors reported.

Other conservationists have argued that de-extinction efforts are newspaper fodder, irrelevant to the formidable political, economic, scientific, and ethical challenges of conserving threatened habitats and species in existence today.

For my part, I see worrying parallels between our present interest in de-extinction and the efforts of the Heck brothers nearly a century ago. This is not to suggest that we are similarly entranced by Social Darwinism, or that today’s resurrection science efforts are bound up with fascist notions of national identity and the need to nurture fantasies of a racially pure past (although the rise of the alt-right would suggest that such forces are by no means extinct themselves).

Still, in this modern world, where genetic ingenuity is advancing as surely as the mercury is rising, we are confronted with other existential threats — from dwindling biodiversity and denuded landscapes, to the droughts, storms, and rising seas that accompany anthropogenic climate change.

Under these circumstances, de-extinction would seem to offer an enticing covenant not altogether unlike the one that so enchanted the Heck brothers and their Nazi patrons. It’s the notion that we might somehow fix the world by manufacturing an idealized version of the past, and then through sheer technological wizardry, drag it into the here and now. Scientists and the public should bring the full force of their scrutiny and skepticism to bear on such wild dreams. Elephants and sage-grouse and so many other creatures that are still with us are threatened with extinction, and we should focus our efforts on saving them.

The mammoths and heath hens of the past can wait.

M.R. O’Connor, a 2016-17 Knight Science Journalism fellow at MIT, writes about the politics and ethics of science, technology, and conservation. Her first book, “Resurrection Science: Conservation, De-Extinction and the Precarious Future of Wild Things,” was named one of Library Journal and Amazon’s Best Books of 2015.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

“The mammoths and heath hens of the past can wait.”

Indeed they can.

As the saying goes, “You are dead a long time.”

Two does not equal three, even for large values of two. The current de-extinction movement is coming from different people with very different motives than the mid-20th C. efforts. To conflate them to what end?

Ms. O’Connor’s argument is essentially one of allocation of resources: Until we’ve assured the continued existence of species alive today, focus all resources on preservation rather than de-extinction. If we all lived together in a petri dish, that might be feasible. But the world is very large and many humans very rich, well able to support many different lines of scientific research at the same time. Both the author (probably) and myself (certainly) believe strongly that more resources should be invested in slowing and stopping the present great extinction. The way to do that is not by discouraging other areas of inquiry (it won’t happen) but by continually coming up with new arguments and data to pry “resources” (love that euphemism) from the pockets of the 1% who own 50% of the world.

The article and journalist who wrote it are utterly missing the point of Rewiliding in a modern sense and makes the assumption that rewiliding would go ahead at the expense of or detriment of extant species. She’s choosing to focus on one, poorly devised attempt at breeding a wild phenotype back into cattle, that happened to fit into the twisted fairytale of a Germanic past that top Nazis dreamed of, utterly ignoring the fact that restoring ecological processes that will benefit extant species is one of the key goals of rewiliding. The animals themselves are large and charismatic, so yes, they carry a certain appeal and having them or close relatives back would be an awe inspiring sight but in one sense they are only tools to increase ecosystem complexity and therefore increase the biodiversity and health of said ecosystem. Rewiliding is NOT about setting back the clock to some arbitrary point in time and trying to recreate that ecosystem, it’s about reinvigorating the truncated ecosystems that humanity has created.

She’s also completely overlooking the fact that rewiliding could be the saving grace for many extant species, giving the potential for insurance populations and vast range expansions in habitat once occupied by similar species, with the additional benefits of restoring and reinvigorating historical ecological processes and relationships between native species and introduced megafauna.

Extremely myopic way to look at it.

NAZI’s are the Alt-Left you imbicile.Wikipedia & Google changed the definition of Facism.

If You stand with the NAZI LGBTQ and the Treansgender agenda or the Facist Left-Wing you deserve what you get,.

Hogwash and historical revisionism. The Nazis were always far-right, and they were obsessed with erasure of LGBTQ+ people. The only imbecile here is YOU.

Um, does “national socialism” mean anything to you? Also known as naziism. Socialism is a leftist ideology. You are patently wrong.

And the People’s Democratic Republic of North Korea is a democracy. Sure.

National Socialism (Nazism) is Fascism which is Alt-Right, Socialism is Alt-Left. Yes that one word (National) makes all the difference…

Science will tell you it’s possible; English majors will tell you why it’s a really bad idea. Hasn’t anyone read Jurassic Park?

I see a remarkable parallel between the Nazis and our society today in the politicization of science to the goal of harnessing its’ results for the furtherment of a particular side’s agenda. The Nazis as a party took the concept of resurrecting an extinct species and attached to it the significance of racial purity and the ostensibly original example of Teutonic power.

Today we see the same in claims of one group being “Science Deniers” in one particular field of study and ignoring the science in another field which does not support their political goals. We as a society have attached political significance to what is, in essence, a tool, that being science, as if the tool itself has meaning outside its’ usefulness as a means of discovery.

Fascism indeed.

We already did this in the Rocky Mountain West in the U.S. 15 years ago they reintroduced Wolves into Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Depending on who you ask, there may have been an error in the genetic coding and science of the reintroduction program. The wolves populated abnormally fast, and started decimating the Elk herds. So, in 2009 they simply opened them up for hunting and harvesting. They are however very timid, and intelligent, and extremely difficult to hunt. Probably wasn’t the best idea. Who knows. Cheers.

Really the Wolf’s ? Yes there were some environmental changes in the early stages of reintroduction. To date none of those exist anymore and that train of thought is so 2010. The Wolf reintroduction into Yellow Stone has put things back as they should be and better environmentally.

I think the historic aurochs had horns pointing forward.

.

The Nazis are convenient whipping toys for those who fail to note that so much of our culture and science is derived from the Romans, who were little more admirable.

.

As a child I was raised with a fascination with regard to mammoths/dinosaurs etc. Visiting the tar pits and such…for family outings. As an adult…I would stand with our scientists that are conducting research in the area of genetics and cloning, Church and his ilk etc. I would choose to be optimistic with regard to our future. I do like the debate as it is interesting. The Nazi tie ins are kinda weird…but so is a lot of our past. Let us face it all and debate it and then do some cool stuff where it makes sense. Life is meant to be exciting so let’s not close doors out of fear of the darkness from our past. Let us figure out the ethics of it all and move forward. Let’s bring some of the animals back if we can! Let’s pick the right ones…the ones that would add value to our lives. These people are my hero’s (George etc.) in a way…I may be in my fifties now…but there is a part of me that is still a young dreamer. Go for it! Perhaps the focus it brings to saving and recovering the best of our environment would pay for itself ten times over. I choose to believe it might.

There is no connection between the Aurochs and the Nazi’s like you present in this article.

The Heck brothers started out in 1927, about 3 years before there was some form of organized Nazi party and 6 years before the Nazi’s came to power.

Goering picked up the Aurochs story, only because he was a fervent hunter, not because he saw Aryan super cows. Only in 1938 were some of the Heck cattle released in Rominter Heide nature reserve. Hitler probably didn’t even know (properly) about the Heck initiative.

By the way, in the same period this thing happened all over Europe, with the Konik pony in Poland and the Sorraia horse in Portugal. I guess we should get rid of those horses too?

The Heck brothers being part of the Nazi party doesn’t mean anything. There was no other choice in that time.

I wrote a book (published) about a resistance hero in the Netherlands. The fact that he was a member of the German Kulturkammer in the Nazi period was also just a way to survive.

And even if they would have been Nazi’s… so what? Should we stop driving Volkswagen as well? What a 2-dimensional correlation to make and to try to politicize animals. Common’

Are the two ideas mutually exclusive? And who are you to decide of what we shall do or not?