Fight Over Dakota Pipeline Shines Light on Nation’s Oil Networks

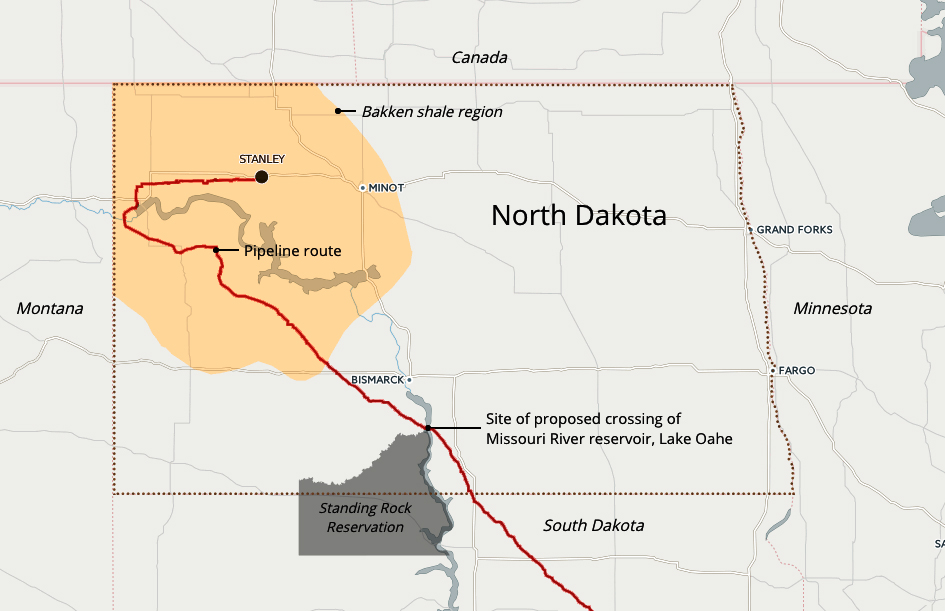

In what has been described as one of the largest gatherings of tribal representatives in history, thousands of supporters have joined local members of the Standing Rock Sioux and hundreds of other Native American nations over the last several months in an attempt to block the Dakota Access Pipeline. The $3.7 billion conduit would transport crude oil from North Dakota’s booming Bakken shale-oil region, through South Dakota and Iowa, and onward to Illinois, where it would connect with existing pipelines.

The pipeline, which will cover more than 1,000 miles from North Dakota to the Midwest when complete, is seen as an economic boon to some. But its proximity to tribal lands and precious water resources is too much for others. Click map to enlarge.

Visual: Undark

At issue: The 1,172-mile pipeline, while viewed by supporters as an economic boon, would abut sacred tribal lands and come uncomfortably close to precious water resources. After weeks of sometimes violent confrontations with police and federal officials, those concerns seemed to prevail, with the Obama administration announcing over the weekend that it would not allow the final stretch of the Dakota Access pipeline to cross the Missouri River at Lake Oahe in North Dakota. Instead, the administration called for a full environmental review and an exploration of alternative routes.

Crowds cheered on Sunday as the news broke, but with the pipeline nearly complete – and a pro-oil Donald Trump just weeks away from inauguration as the nation’s new president – the latest decision may have little impact on the project’s ultimate completion.

Whatever the final outcome — and aside from real and pressing issues like tribal rights, or whether, given the imperatives of climate change, additional fossil fuel infrastructure is a smart move — the battle over the Dakota Access project, like the infamous Keystone XL fight before it, also raises a simple question: How safe are modern oil pipelines, and are there better ways to move crude?

Over 70,000 miles of crude oil pipelines — most of them underground — spread like vasculature beneath the earthen skin of the United States. Those conduits, sometimes wide enough for a person to shimmy through, transport around one billion gallons of oil every day from production fields to refineries, and they help to satisfy the nation’s oil habit, which amounts to about 19.4 million barrels (or 814 million gallons) of oil consumed every day, on average. But with that much oil and that much pipe — enough to circle the globe nearly three times — accidents are inevitable. In fact, since 2010, there have been more than 1,300 crude oil spills in the United States, according to data collected by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, a regulatory arm of the U.S. Department of Transportation:

That’s one crude oil spill every other day.

According to PHMSA, most of these incidents are contained by pipeline operators, and the majority of the spilled oil is recovered. Of the 8.9 million gallons spilled since 2010, the agency has reported that over 70 percent, or 6.3 million gallons, has been recovered. Filtering PHMSA data to look at spills in onshore water crossings only, like rivers, however, the recovery rate drops to just 30 percent. Underwater or elsewhere, small leaks and ruptures can go (and have gone) unnoticed for days — even weeks — before companies manage to detect the problem and shut the pipeline down.

In the meantime, that underground seepage can quickly reach devastating volumes. Rivers contaminated by oil spills can take sometimes take years and hundreds of millions of dollars to remediate. And despite intensive cleanup efforts, the presence of spilled hydrocarbons can sometimes persist in soil and aquifers for decades.

Crude oil courses through pipelines at astonishingly high pressures — sometimes at more than 1,000 pounds per square inch, equal to the pressure felt more than 2,300 feet underwater. What may start as a small leak brought on by corrosion or negligent maintenance can end up spilling hundreds of thousands of gallons of poisonous crude oil and its accompanying chemical lubricants into fields, rivers and aquifers with breathtaking speed. That’s in spite of carbon steel pipes and reinforced walls that can reach almost one inch in thickness.

Making matters worse, aging pipeline, much of it built of wrought iron and bare steel, is especially vulnerable to the elements. About 45 percent of all crude oil pipeline in the United States — more than 30,000 miles — was installed before 1970. About 7,000 miles are made of pipe that was laid before World War II. “This is where corrosion rears its ugly head,” says Paul Bommer, a senior lecturer in the department of petroleum and geosystems engineering at the University of Texas at Austin. “Corrosion nibbles away at the thickness of the pipe until finally the pipe isn’t thick enough and it doesn’t matter what the strength of the steel is anymore.”

“When the hole finally gets deep enough, it’ll get a leak,” Bommer continues. “With 1,000 psi, you can push a lot of fluid through a small diameter hole and probably nobody notices until it starts bubbling up in someone’s field.”

In 2013, that’s exactly what happened in Tioga, North Dakota, when a wheat farmer’s combine tires became coated in crude more than a week after an underground pipeline sprang a leak from a dime-sized hole in a 6-inch pipe. In all, about 870,000 gallons of crude were spilled. Tesoro Logistics, the pipeline operator responsible for cleaning up the spill, spent $42 million and two years mopping up and processing the contaminated soil.

Waterfowl rescued from a pipeline spill near Kalamazoo, Michigan in 2010. More than 800,000 gallons of crude were dumped in what became the most expensive on-shore oil spill in U.S. history.

Visual: USFWSmidwest/Flickr/CC

Three years earlier, a crude oil pipeline ruptured along a problematic section of pipe and spilled 843,000-gallons into a tributary of the Kalamazoo River in Marshall, Michigan. That eventually became the most expensive on-shore spill in U.S. history, costing Canadian pipeline operator Enbridge $1.2 billion in clean-up and environmental restoration. An investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board found that an 80-inch gash had gone unnoticed by the pipeline control center for full day. For 17 hours, Enbridge continued feeding oil into the leaky line.

The possibility of a similar rupture occurring at some point along the new Dakota Access Pipeline is what had many protesters flowing to North Dakota in an attempt to block, or at least re-route, that pipeline. Critics of the Dakota Access project have called for a reevaluation of the pipeline’s proposed trajectory, arguing that developers did not sufficiently consider its environmental impacts. Chief among the questions: How would a spill play out if the pipeline began leaking at one of its many river crossings? The conduit, which would move almost 20 million gallons of crude oil per day at 1,440 psi through pipe with walls less than an inch thick (the range is between 0.429 and 0.625 inches thick, according to Energy Transfer Partners, the company building the pipeline), could foul key agricultural and drinking water resources for the Standing Rock Sioux tribe and others.

The most sensitive water crossing in this regard is undoubtedly the Missouri River, and at some point in North Dakota, if the project is to complete the link from the Bakken to the Midwest, the pipeline will need to cross it. Under normal circumstances, and like most pipelines, the Dakota Access pipeline has been laid, link by link, into excavated trenches, and then buried under at least three feet of soil. Where the pipeline must slip under more sensitive features — crop land, highways, rivers — it is tunneled much deeper.

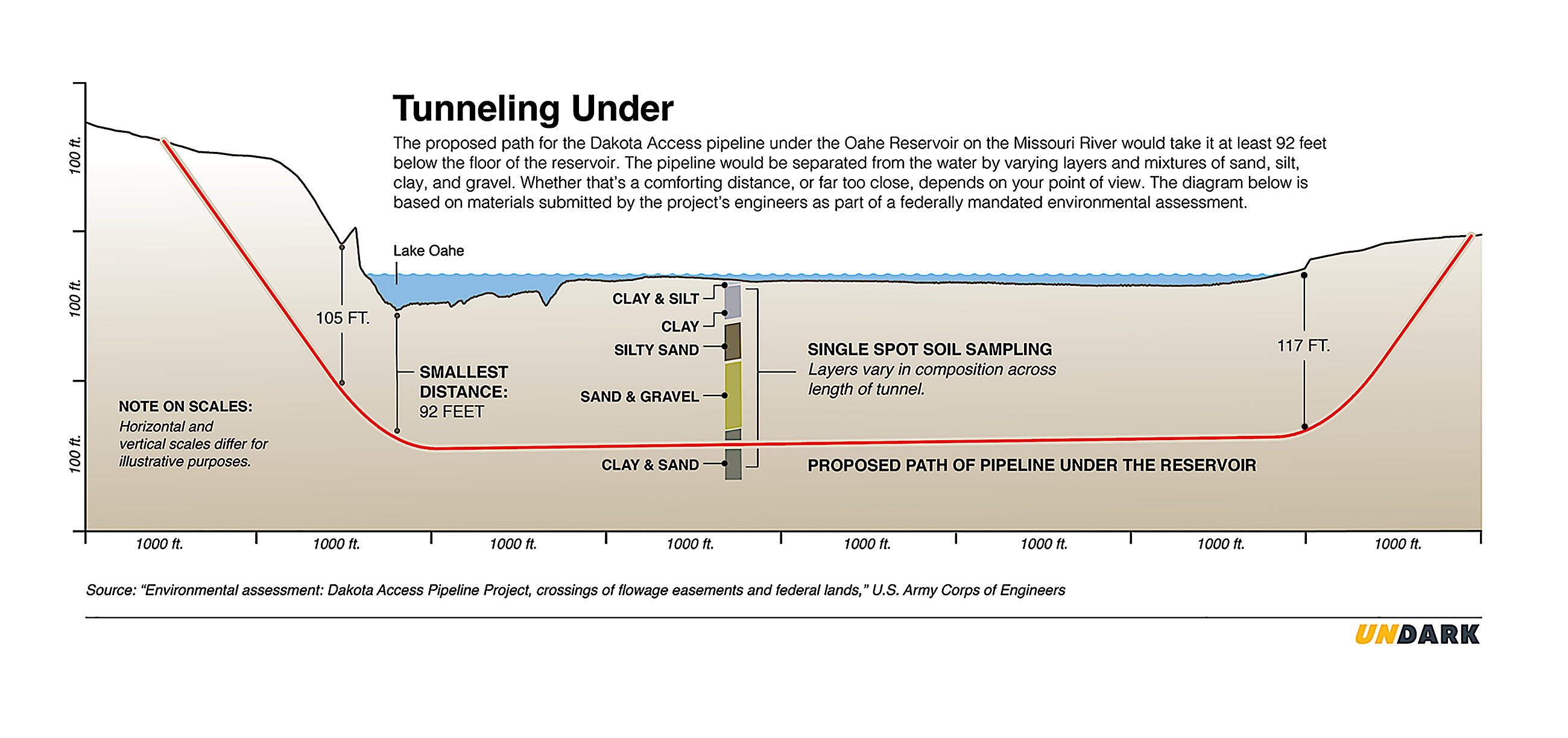

In breaching the Missouri, Energy Transfer partners had planned to bore a tunnel some 7,800 feet long underneath a reservoir along the river known as Lake Oahe. Federal guidelines require pipelines to be at least 3 feet below the natural bottom of water sources that are less than 12 feet deep, but the Dakota pipeline would run far deeper, says Michael Rosenfeld, chief engineer with Kiefner and Associates, a technical services provider to the pipeline industry. That’s because engineers use horizontal directional drilling — the same technology that has helped to unlock vast amounts of deep shale oil and gas in the first place — to carve a long, gently sloping tunnel beneath those surface features being avoided. Once the bore hole is complete, a pre-welded and pre-inspected section of high-yield strength steel pipe is then threaded through and connected to the rest of the pipeline.

“You may be 40 feet under the river or the highway and it’s a continuously curved path,” says Rosenfeld, explaining how long and deep the tunnel must be to allow for a slight bend in the large-diameter steel pipeline. That also means that pipelines typically make their deeper dive underground a significant distance from the feature they are slipping under — and that depth and distance could be a silver lining, Rosenfeld says, as they can help protect both the resource being avoided, and the pipeline itself. “It does wind up typically being installed fairly deep which generally is to its benefit because rivers can flood or erode their banks and this keeps the pipe well away from areas where it can get exposed to those kinds of natural processes.”

Drawings submitted to the federal government as part of the Dakota Access project’s environmental impact assessment suggest that the pipeline would be anywhere form 92 feet to as much as 117 feet beneath the nominal bottom of the Oahe reservoir.

Of course, for all of this technical derring-do, underwater geography is constantly in flux, and oil leaks have been known to spring from pipelines nominally buried deep under river bottoms — often with disastrous results. A pipeline that slipped some 8 feet below the bottom of the Yellowstone River, for example, was found to be fully exposed on the riverbed and leaking thousands of gallons of oil — just a few years later. In recent years, oil has seeped up from pipelines beneath wetlands near the Kalamazoo, and underneath culverts built for caribou crossings in Alaska.

Just this week, a “significant” pipeline leak was found to be spilling oil into a tributary of the Little Missouri River near Belfield, North Dakota. “The incident was reported by a landowner who saw oil leaking from the 6-inch pipeline into the creek,” The Grand Forks Herald newspaper noted.

For its part, Dakota Access, LLC, a subsidiary of Energy Transfer Partners, says it’s employing the latest technology to inspect and periodically monitor the Dakota Access conduit — and that these safety measures mean an oil spill into the Missouri River is improbable. “The depth of the pipeline below the respective rivers … and the design and operation measures that meet or exceed the respective Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) regulations make a release into either waterbody very unlikely to occur,” the company declared in an environmental assessment.

Matthew Horn, a senior scientist with RPS Group, a consultancy firm that performs risk assessments and spill modelling for pipeline projects, including the Dakota Access, repeated that assessment in a phone call. With the pipeline dozens of feet below layers of sand, clay, and rock, the earth would act to slow the movement of oil should a leak occur, giving responders time to detect and address the problem. “If you’re 92 feet below a river and we’re talking about maybe a barrel of oil a day, that’s not going to transport anywhere quickly,” Horn said. “It’s not as though you’ll have a leak and see a giant oil slick on the river right away.”

Pipeline spills are a messy business. Above, an excerpt from the Vice documentary “Pilpeline Nation.”

A burst weld or a full bore rupture, on the other hand, would send oil “tens of kilometers down the river,” Horn said.

Spill and environmental risk models for the Dakota Access project’s proposed Lake Oahe crossing were submitted as part of the environmental assessment required by federal law. But as noted by Jo-Ellen Darcy, the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works) who issued the decision to halt the project last weekend, those spill models have been withheld from the public “because of security and and sensitivities.”

Representatives of Energy Transfer Partners and Dakota Access LLC did not respond to requests for comment on the safety of its pipeline, or on the recent Obama administration to reconsider its route under the Missouri. But a public relations specialist representing the company, Lisa Dillinger, provided a fact-sheet outlining the various safety measures it intends to employ once the pipeline begins operating. These include: aerial and ground inspections every two weeks; “24/7 monitoring” from a control center with the ability to shut down the pipeline remotely or in person; and the use of a so-called Advanced Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition system “to constantly monitor sensing devices placed along the pipeline to track pressure, temperature, density, and flow.”

In addition to those measures, federal law requires the operator inspect the pipeline every five years using “smart pigs,” tools that move through the pipe and measure indentations, buckles or evidence of corrosion in the pipe. Shut-off valves before and after the river crossing are also required by law, Rosenfeld notes. “There have to be shut-off valves on the upstream side and backflow check valves on the downstream side to protect that waterway,” he says.

In the case of an oil spill, those valves can be shut off remotely – from as far away as Houston, Rosenfeld says.

Many regulatory reform advocates would like to see more frequent pigging than every five years, and not everyone has faith in other established safety regimes — even if they are enshrined in federal code. Should oil reach the Missouri River or another body of water, drinking water intakes would be threatened. It’s a worst-case scenario that many parties have raised, including the Environmental Protection Agency, in a letter dated March 11:

“Our experience in spill response indicates that a break or leak in oil pipelines can result in significant impacts to water resources. We note the capacity of the proposed DAPL is 13,100 to 16,600 gallons per minute of crude oil. Despite the expectation of a low probability of a significant spill reaching the Missouri River and lakes, the proposed Missouri River crossings are located 10 miles above the Fort Yates and 15-20 miles above the Williston, North Dakota, drinking water intakes. There would be very little time to determine if a spill or leak affecting surface waters is occurring, to notify water treatment plants and to have treatment plant staff on site to shut down the water intakes.”

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe plans to move to a new water intake roughly 70 miles downstream from the pipeline crossing as early as next year. That might alleviate some of the risk, but concerns over the Oahe crossing have continued to mount. A pipeline safety consultancy hired by opponents of the Dakota Access project suggested just last month, for example, that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had likely underestimated the potential for the new crude oil pipeline to spill into the Missouri River — and overstated the ability of operators to identify major spills.

Energy Transfer defended the Army Corps analysis, and insisted that the environmental concerns attending the pipeline had been “adequately addressed.”

That sort of back-and-forth is not all that surprising, given the stakeholders on all sides, but it’s worth noting that, while disasters have happened, pipelines overall have a relatively clean track record. The overwhelming majority of the 350 billion gallons of crude oil transported every year in the U.S. reaches its destination.

Of course, no two oil spills are the same and environmental remediation efforts can take years, as the impacts of residual chemicals on natural resources like land, water, and wildlife linger. The larger the spill, the longer lasting the effects and the deeper the environmental harm, which can range from wildlife mortality to long-term health effects in humans, including to spill cleanup workers.

Still, according to Sarah Stafford, a professor of economics at William & Mary who has studied pipelines and government regulation, the alternatives to pipelines are far more worrisome. “For all the problems that pipelines have, they’re probably the safest means of transport,” Stafford says. “It’s better that it’s in a pipeline than in a railcar or on a highway.”

That, of course, is an argument that has been made many times in the past — and it’s one that environmental advocates call a red herring. During the fight over the Keystone XL pipeline, for example, the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Washington D.C.-based environmental advocacy group, argued that the construction of pipelines would do nothing to stop the disasters associated with transporting crude oil by train, because oil companies were still keen on using both modes of transport.

Advocates say the same is true with the Dakota Access project. “You have to look at the economics of North Dakota,” says Jesse Coleman, a researcher with Greenpeace’s U.S. investigations team. “They’re already getting it out by rails and they will continue to. They’re not going to stop using the rail system because they built this pipeline.”

While crude oil shipments by rail are down nationwide compared to the same time last year, North Dakota is still booming: “The Bakken region has accounted for the vast majority of rail crude oil originations in recent years,” according to a November 2015 report from the Association of American Railroads. Completion of the Dakota Access Pipeline may affect rail traffic, but it won’t stop it in its tracks, predicts Coleman. And unless Americans lose their appetite for fossil fuels, the country’s extensive web of crude oil superhighways will keep humming along.

“Until the day comes that people aren’t using the volume of fuel that we use day in and day out, there’s no other way,” said Bommer, the University of Texas engineer. “Those pipelines, we can’t do without them.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Put the pressurized oil-carrying pipe inside a “catch pipe”. Don’t bury it. The catch pipe can have sensors, cameras can travel in it to monitor. If, your serious about having that pipe. You would go to these extremes to protect your investment. Praise God for forward thinking that cares for all creation!

Hi Belinda, pipelines are buried to protect them from vandalism, mechanical damage, natural disasters, etc. Buried pipelines are externally coated and cathodically protected to control de corrosion rates when the coating degrades, breaks, disbond. Inside the pipeline, corrosion inhibitors are added to the crude mix to also inhibit corrosion. A “catch pipe” is triky, depending on the design a catch pipe could lead to condensation and temperature changes making a corrosion-friendly environment. Every so often a sensor aka a “pig” travels along the pipeline and measures mechanical and electrochemical flaws. However, the pipeline sensor technology nowadays is still limited but it is envisioned that in the future sensors will be placed along the whole pipeline and predict failure. My intend of this reply is to share some of my expertise with you not to criticize your reply. Many engineers and scientist are working on making our pipelines safer! I dont have a stand on the N. Dakota pipeline issue, I am educating myself about it.

With the pipeline dozens of feet below layers of sand, clay, and rock, the earth would act to slow the movement of oil should a leak occur, giving responders time to detect and address the problem. “If you’re 92 feet below a river and we’re talking about maybe a barrel of oil a day, that’s not going to transport anywhere quickly,” Horn said. “It’s not as though you’ll have a leak and see a giant oil slick on the river right away.”

Other possibilities of increased risk buried deeper, and the length of the pipe:

The above statements mostly say the pipeline planned to go under Lake Oahe has increased safety due to the depth below the lake that the pipeline is planned for. The statement by Horn suggests that the monitoring system would definitely detect a leak before enough oil spilled to contaminate the lake. This assumes the monitoring system works correctly and works at all. The system is made by people, therefore it could fail. If it does fail, there is a lot more oil that will be contained in the increased depth of soil, than would be in a shallow tunnel, also the increased depth increases pressure on the pipe, as well as the pressure from the body of water, the lake resting on the soil above the pipe. If the monitor does not work, by the time the oil percolates to the top of the soil, which is the bottom of the lake, and then the oil rises to the top of the lake where it can be seen, after a possibly significant amount of time that a person happens to be there to observe the oil, the quantity of oil will be so large, the clean-up will be extremely difficult, in addition to the logistics of removing oil from soil underneath a lake. In addition the logistics of assembling and installing a pipeline that deep, for a length of 7,800 feet without any mistakes is extremely difficult; adding to the risk there will be mistakes which could cause a leak. Also the wider the body of water that is being crossed also increases the risk that there will be an oil leak into that body of water, so a 20 foot wide tributary would be safer to cross than a mile wide lake. If there is a one in a million chance of any one inch of pipe developing a leak, than two sequential inches has a 2 in a million chance, 2000 inches has a 2000/1000000 or 0.2 percent chance, and any one of the inches in 7,800 feet has a 9.36 percent of a leak, almost 10 percent, that is way too high of a risk for contaminating a major water source. Any one of those 93,600 inches that develops a leak will contaminate the lake equally.