Precious Cargo: The Endangered Species Act and the Case of the Yerkes Chimps

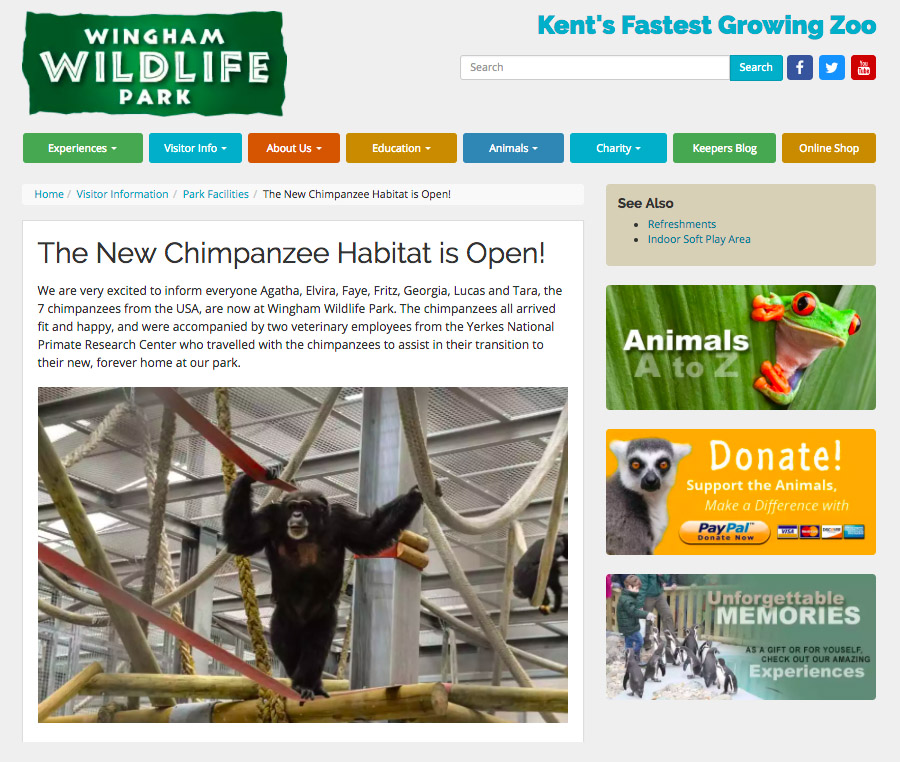

In late October, an SUV hauling a trailer bearing seven cages marked “live animal” pulled into Wingham Wildlife Park, a zoo in Kent, England. The cages had been loaded off a plane that flew across the Atlantic from Atlanta and were “carrying a very precious cargo, one the park has been working on for more than three years,” according to a press release issued soon after.

The cargo: seven chimpanzees, aged 21 to 39, all of whom had been the subject of behavioral research for decades at Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University in Atlanta. Their usefulness in that regard ended last year, when the federal government stopped funding experiments involving the primates, and listed captive chimpanzees as an endangered species.

Their arrival in the U.K. signaled the end of a drawn-out battle pitting animal rights groups, legal scholars, and many scientists against both the Yerkes lab and Wingham park — a saga that reached its climax in September when a federal judge struck down the final challenge of activists who had sued to block the shipment of the chimpanzees abroad. That cleared the way for the journey to Wingham — but in issuing her decision, the judge also delivered a stinging rebuke of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the federal agency that issued the original permit to Yerkes for shipping the animals, and whose mandate includes enforcing the Endangered Species Act.

The agency’s broad interpretation of the act, U.S. District Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson declared, “appears to thwart the dynamic of environmental protection that Congress plainly intended when it mandated that no export of endangered species be allowed.”

The judge’s ire, along with that of a growing chorus of primate researchers, wildlife advocates and legal experts, was drawn by the agency’s practice of allowing the sale, import, or export of endangered animals — all nominally forbidden by the Endangered Species Act, or ESA — if the permit applicant makes a donation, sometimes a very small one, to an organization that protects the species in question. Critics call this little more than a “pay-to-play” scheme that benefits labs and zoos — and even trophy hunters and amusement parks — while providing negligible dividends for endangered species. Transactions under these arrangements have involved everything from elephants and tigers to South African penguins and rare black rhinoceroses — all of them changing hands under pay-to-play arrangements that involved donations for as little as $500.

In June, U.S. Rep. Brendan Boyle, a Democrat from Pennsylvania, said that his office had compiled information suggesting that “virtually every one of the more than 1,300 [Endangered Species Act] permits given out in the last five years involves this pay-to-play scheme,” and he called on the Fish and Wildlife Service to halt the practice. “This unauthorized loophole allows people to buy their way out of the species protections of the ESA,” Boyle said in a statement issued at the time, “and undermines our collective, global efforts to protect endangered and threatened animals from harm and abuse.”

For its part, the Fish and Wildlife Service has publicly maintained that the Endangered Species Act explicitly makes room for these sorts of transactions. In a statement forwarded by Vanessa Kauffman, a public affairs specialist with the Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency said that it considered the Yerkes application “on its merits in determining whether the legal requirements of the Endangered Species Act were met.”

“The Service disagrees with assertions that the issuance of this permit fails to safeguard the spirit or letter of the ESA,” the statement added.

But opponents suggest that only the broadest interpretation of the Endangered Species Act would allow the sorts of donation brokering that was ultimately revealed in the Yerkes case — and Judge Jackson seemed to agree. Katherine Meyer, the attorney who represented the groups that sued to stop Yerkes from shipping the chimpanzees overseas, said the judge’s comments marked “the first time we’ve had a federal judge express skepticism about whether pay-to-play is legal.”

The heart of the issue is a single line in Section 10 of the 1973 Endangered Species Act. While the law clearly prohibits buying, selling, importing, or exporting endangered species, Section 10 allows the agency to make exceptions if an applicant seeking permission to do one of these things can demonstrate that the activity is “for scientific purposes or to enhance the propagation or survival of the affected species.” In practice, critics say that “enhancement” clause has too often come to mean that if the applicant donates a token sum to a suitable group or organization, then the federal agency is likely to issue a permit.

An examination of email correspondence between the Yerkes lab and the Fish and Wildlife Service, available in the public record, sheds light on how such transactions unfold.

The case’s paper trail starts in June of last year, when Yerkes sent a letter to the Fish and Wildlife Service. Just three paragraphs long, it inquired about a permit to ship eight chimpanzees from its labs in Atlanta to the Wingham Wildlife Park in Britain. (By the time the permit was granted, one of the chimpanzees had died.)

The letter was accompanied by a $100 money order and 41 pages of additional information —mostly about the animals themselves, and how they would be shipped overseas. The only hint of urgency was an enclosed Federal Express shipping label — provided so the Fish and Wildlife Service could easily return the export permit as soon as it was ready.

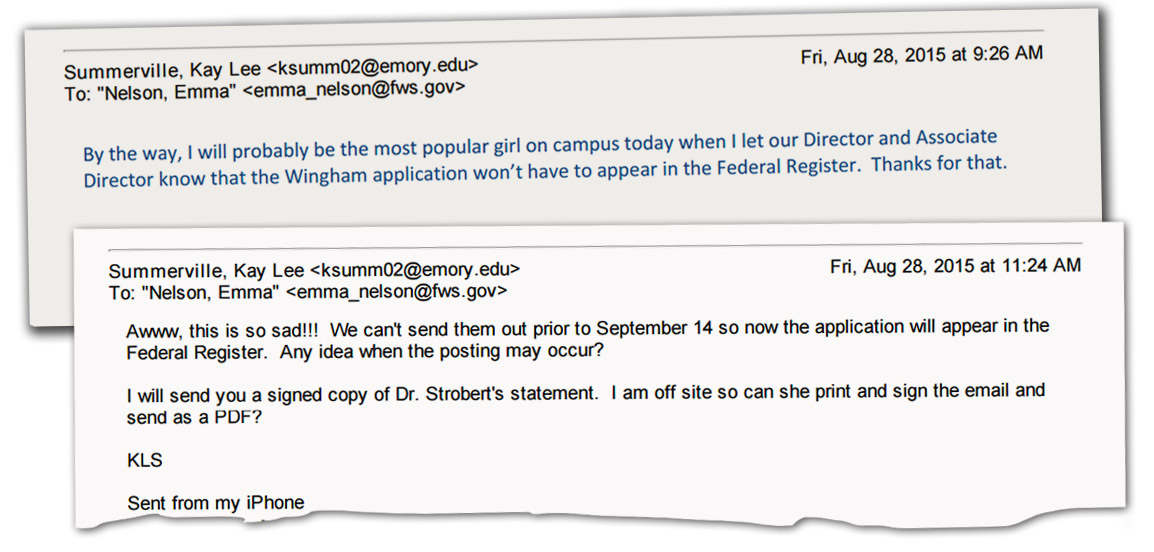

For the next several months, the federal agency would ask for more information about the chimpanzees and the facility in Britain, and Yerkes would reply in kind. By the end of August, Kay Lee Summerville, a senior program coordinator for the lab who had been leading Emory University’s correspondence with the Fish and Wildlife Service, wrote an email to the agency with concerns about whether the application would be listed in the Federal Register. This would make it open to the scrutiny of the public — including wildlife conservation groups, scientists and others who oppose pay-to-play.

At first, a permit biologist at the agency, Emma Nelson, said that publishing in the Federal Register would not be necessary, because at the time, captive chimpanzees were listed as a “threatened” species, but not “endangered” — a distinction that hinges on whether a species is likely to be at the brink of extinction in the near future, or if it has already reached that point.

Summerville was clearly relieved that the transaction would not be made public. “I will probably be the most popular girl on campus today,” she wrote back to Nelson on August 28.

Not long afterward, however, the federal official backtracked. As of September 14, 2015, the status of chimpanzees under the federal law would officially change to endangered, she told Summerville. Unless the chimpanzees were shipped abroad before that date, then yes, the application would be mentioned in the Federal Register. “Awww, this is so sad!!!” Summerville replied. “We can’t send them out prior to September 14.”

“Any idea,” she added, “when the posting may occur?”

When asked about the correspondence, a spokeswoman for the Yerkes lab, Lisa Newbern, said the exchange with the Fish and Wildlife Service about the Federal Register simply demonstrated the center’s interest in getting everything right with regard to the shipment of an “up-listed” animal. “Given this was the first chimpanzee Endangered Species permit application impacted by the up-listing, the Yerkes National Primate Research Center had a number of questions about the lengthy application process,” she wrote in an email to Undark.

Nelson didn’t respond to Summerville’s question about the timing of the posting, but her next message explained the central detail that would inform the rest of the application — and the case itself. Since the chimpanzees would soon be considered endangered, Nelson wrote, Yerkes “would need to provide information on how the purpose of this export meets the criteria for ‘enhancing the propagation or survival’ of the species.”

Yerkes could have argued that the action of exporting the chimpanzees to a zoo would somehow accomplish this goal. Instead, it followed the agency’s own suggestion: “Enhancement may be … indirect, such as contributions that are made to in situ conservation.”

On September 25, the Yerkes lab sent a letter to the Fish and Wildlife Service announcing its intentions to make a donation — “as a condition of grant of this permit application” — to the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Uganda-based Kibale Chimpanzee Project, “both of which support chimpanzees in the wild,” the Yerkes email stated. The total amount to be donated was a little less than $4,000 per year for five years, or approximately the cost of taking care of one chimpanzee for a year. In other words, shipping the chimpanzees to Wingham, and paying the two groups a donation, would still wind up saving Yerkes money, since taking care of all seven cost the lab about $1.4 million a year.

The letter goes into detail about the laudable work of the two organizations, and how the donations should “satisfy the enhancement requirement for grant of an ESA permit.”

Before the Fish and Wildlife Service could fully evaluate the proposal, however, Richard Wrangham, a professor of biological anthropology at Harvard University and the founder of the Kibale project, co-authored a stern letter to both Wingham and Tim Van Norman, chief of the permit branch in Fish and Wildlife Service’s International Affairs Program. Wrangham and his colleagues said that their organization had been misled about the whole affair, and that it had thought Yerkes already had a permit. Further, after looking into Wingham and finding, among other things, that the facility lacked accreditation by a European zoo association, Wrangham and his colleagues said the Kibale organization was very much opposed to the idea of shipping the chimpanzees there. Both Atlanta’s Yerkes lab and Britain’s Wingham facility, the Kibale group complained, “were using [Kibale] as leverage for obtaining a chimpanzee exportation and transfer permit.”

Newbern, the Yerkes lab spokeswoman, disputed this account, insisting that the Kibale organization had reached an agreement with Wingham. The Wingham facility itself did not respond to several queries on this point.

In an interview with Undark, Wrangham called the application “shady.” He also says he remains concerned about the impact such transactions could have on the international stage — especially in countries where wild chimpanzees are native. “I feel it will be noticed by host countries and [legitimize] the notion of pay-to-play,” Wrangham said. “The implication is that anybody who wants to and has enough money can buy their way out of the [Endangered Species Act],” Wrangham added, “and do anything they want with protected animals and harm not just the individual animals but conservation efforts overall.”

Meyer, the attorney representing the New England Anti-Vivisection Society, an animal rights group and the lead plaintiff in the case against Fish and Wildlife, called the issue particularly disconcerting. She noted that not only did the permit application appear to fumble in locating an organization to receive a donation, but also in pledging that Wingham would follow European Endangered Species Program guidelines if it decided to breed the chimpanzees.

The EEP, Meyer noted, actually wound up opposing the transfer.

Within three weeks of the Kibale donation proposal falling apart, Van Norman of the Fish and Wildlife Service wrote to Joyce Cohen, associate director of the Division of Animal Resources at Yerkes. “I am currently in South Africa for a meeting … [where] I met David Johnson of Population and Sustainability Network,” Van Norman wrote. Although the group had never worked with chimpanzees, it had an idea, he said, “that may be right up Yerkes’ path.”

In June, U.S. Rep. Brendan Boyle, a Pennsylvania Democrat, called on the Fish and Wildlife Service to end the so-called practice of pay-to-play, which he said undermines efforts to protect endangered species.

Visual: Cheltenham Democrats/Flickr/CC

Van Norman promised Cohen that he would feel out the possibility on his return to Washington. “In the meantime,” he wrote, “we will continue with our current processing of your application. I am sorry for the confusion but I think we may have a very good road forward.”

In the end, both Yerkes and Wingham followed the Fish and Wildlife official’s lead. They agreed to give $45,000 a year for five years to the UK-based Population and Sustainability Network (PSN) for a project premised on the idea that human population control and healthcare can contribute, indirectly, to the preservation of chimpanzee habitat in Africa.

Observers of the case seize on this twist as further evidence of the breakdown in enforcement of the Endangered Species Act.

“Here’s a federal agency, and an applicant submits information on breeding and donations, and when the Fish and Wildlife Service finds out the information’s not correct, you’d think they would deny the permit,” Meyer said, “but instead they come up with a new recipient for the money.”

That sentiment was echoed by Delcianna Winders, a fellow at the Animal Law & Policy Program at Harvard Law School. “The fact that FWS is so proactively doing the work that the applicant is supposed to be doing shows how FWS is bending over backwards to help the very industry that it’s supposed to be regulating,” she said, “to buy their way out of compliance with the law.”

Holly Doremus, a professor of environmental regulation at the University of California-Berkeley Law School, said such critiques hinge on two key concerns. First, she said, any fair reading of the Endangered Species Act suggests that the federal government should “just be looking at the proposed activity and seeing if it would enhance the survival of the species.” In other words, Fish and Wildlife should have only assessed whether shipping the Yerkes chimpanzees from Atlanta to Kent would enhance the survival of the species overall, and not whether Yerkes was also undertaking some third, unrelated activity, such as donating money to a chimpanzee sanctuary in Uganda — or to a group focused on human population and reproductive health issues.

Further, Doremus noted, “nothing in the regulations explains how they do ‘enhancement’ evaluations.” That is to say, there is no clear way to determine if the propagation or survival of the species in question is actually enhanced.

Representatives of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service refused to make an official available to answer specific questions related to the Yerkes case and its correspondence with the lab. In an email message, Kauffman, the public relations specialist with the agency, forwarded a five-paragraph statement outlining the agency’s understanding of the Endangered Species Act and how it interpreted the notion of “enhancement.”

According to that statement — which both Kauffman and the agency’s chief of public affairs, Gavin Shire, said was not attributable to any one official — in cases involving the import or export of live captive-bred animals, “enhancement is usually provided through the generation of revenue in support of established conservation programs that contribute to in improving [sic] the status of the species in the wild.” The statement further indicated that the Fish & Wildlife Service monitors donation activity “through the applicant’s submission of annual reports, information provided through our grants programs, and other sources.”

In response to a follow-up email posing questions specific to the Yerkes case, including the scrubbed Kibale donation and the subsequent brokering of the Population and Sustainability Network deal, Kaufman forwarded another statement: “Although we consulted with the applicant in the process of reviewing the original application and subsequent amendments, we did not dictate a specific financial contribution, including amount or intended recipient, in that review process.”

Still, it is worth noting that although the the Fish and Wildlife Service says it allows donations to be made to “established conservation programs,” Van Norman admitted in an email dated November 23 — well after the Population and Sustainability Network’s board of directors had already agreed to accept the Yerkes donation — that he had not yet looked at the organization’s website to learn of its earlier work.

Multiple requests for an on-the-record discussion with a Fish and Wildlife Service representative involved in ESA permitting were declined.

The issues surrounding pay-to-play — including this case — have resonated beyond U.S. borders. Doug Cress, coordinator of the Great Apes Survival Partnership (GRASP), a United Nations program based in Kenya, said his inbox filled with queries last fall from organizations that Yerkes had approached in its quest to offer a donation or donations. The messages came from Uganda, the U.K., Denmark, Kenya and Cameroon.

“We told them to turn it down,” he said by Skype from Nairobi. A donation, Cress explained, would simply exploit what is essentially a loophole in U.S. law. “All you’re really doing if you’re paying a small donation to a program in Africa so you can move seven chimpanzees to [a zoo in the U.K.] … is divesting yourself of your responsibilities in the U.S.”

“The U.S. has a high number of sanctuaries equipped to handle captive chimpanzees,” Cress continued, calling the shipment of the animals to the Wingham facility “a clumsy disposal of highly sentient beings that deserve better, and it holds no connection to conservation and species protection.”

Though activists still question why Wingham was chosen in the first place, Lisa Newbern, of Yerkes, insisted in an email that Emory’s “motivation always has been and will continue to be doing what we believe is best for our center’s animals and human health.”

“That some sanctuaries have now volunteered to take our chimpanzees doesn’t present a full picture of the challenges involved in finding appropriate options for the retirement of chimpanzees,” she continued, “including their capabilities and the fees they charge to provide lifetime care, as well as their ability to fulfill our extensive evaluation criteria.”

Patti Ragan, founder of the Center for Great Apes, a sanctuary in Wauchula, Florida, is one of four sanctuary directors who approached Yerkes about receiving the chimpanzees, according to the New England Anti-Vivisection Society. The center is one of seven in the U.S. that is certified by the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries. Ragan said she called Yerkes earlier this year to tell them she could accommodate the chimpanzees. “I let it be known we had space,” she told Undark. Yerkes officials told her they had already planned to ship the primates abroad.

In a separate email, Newbern also took care to note: “I hope you will not position our donation decisions as merely financial, because that would be inaccurate” — meaning, Yerkes did not send the chimpanzees to Wingham merely to save money. She also noted that Wingham did not pay Yerkes for the chimpanzees.

Asked about the difference between a zoo and a sanctuary, Ragan noted that their missions are distinct. “Zoos offer exhibitions for the public, while sanctuaries are not open for the public and focus on rehabilitative care,” she said.

For its part, Wingham began advertising the chimpanzees soon after their arrival; a recent Facebook post featuring photos of the chimpanzees in their first venture outdoors received more than 1,000 “likes,” and local residents are quickly buying up items the zoo has listed on Amazon.com to donate to the chimpanzees — from tennis balls to mustard.

In the end, Meyer — the attorney who represented plaintiffs attempting to block the Yerkes permit — said the case remains noteworthy in large part because of the issues Judge Jackson raised. Though Jackson found that opponents lacked standing to challenge the transfer, their arguments raised “significant legal issues.” Among these, she wrote: “[W]hether or not the ESA actually authorizes FWS to permit the exportation of endangered species whenever the agency can somehow conceive of a way in which the act of granting the permit (as opposed to allowing the permitted activity) benefits the species of animal that is being exported.”

She also went on to comment on pay-to-play directly, saying the Fish and Wildlife Service appears to see ESA’s provisions as offering “a green light to launch a permit-exchange program wherein the agency brokers deals between, on the one hand, anyone who wishes to access endangered species in a manner prohibited by the ESA — and has sufficient funds to finance that desire — and on the other, the agency’s own favored, species-related recipients of funds and other services.”

Lori Gruen, a philosophy professor at Wesleyan University who has written extensively about ethics and animals, said that Yerkes missed an opportunity to make itself look good by not releasing these chimpanzees to local sanctuaries, several of which are within driving distance from Atlanta. Gruen, who has documented the fate of chimpanzees used for research in the U.S. on a website called thelast1000chimps.com, said that the seven chimpanzees Yerkes shipped to England were family members of the very first chimpanzees brought to the U.S. for research, nearly a century ago.

“It would’ve been good public-relations to announce that descendants of the first colony were finally being retired,” she said.

To date, Yerkes still has 47 chimpanzees in its labs.

Timothy Pratt is a reporter based outside Atlanta. He writes about subjects ranging from soccer to science to higher education, in English and Spanish, for a range of outlets that includes The New York Times, The Guardian, and the Columbia Journalism Review.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Should we not stick to some basics regarding endangered species? What should our intentions be? To increase their numbers so they can be de-listed and to give them back their home. Increased habitats. Any decisions on their fate should be based on supporting these two end goals. Thoughts?

It breaks my bleeding heart to see them in a ZOO- you could literally see the one chip who chose to NOT venture outside because of the onlookers gawking at him and his friends, Can you blame him, NO- ya CAN NOT- I TOO PEITIONED AND WROTE LETTERS TO NOT SEND THEM TO UK \OO BUT INSTEAD SHIP THEM TO CENTRE FOR GREAT APES ONE OF THEE BEST SANCTUARYS IN NORTH AMERICA –

Those ‘onlookers gawking’ are caregivers. While it is not the ideal result for the chimps by any stretch of the imagination, they are loved and cared for at Wingham- and are NOT forced to be in public view. Jane Goodall herself has praised the facility provided for the chimps. It’s sad that the chimps didn’t make it to a sanctuary, but that does not mean that they are not well cared for at the zoo. Some of the best care and facilities (if not THE best) I’ve seen for chimps has been at a zoo- zoos can do great things for their animals.

I agree with Amy. As someone lucky enough to care for Washoe and her family, I have followed the story of the Yerkes chimps for years. I now follow the Wingham facilities and the care and consideration they give to the needs of the chimps seems exemplary. Lots of us in the UK care just as much as anyone about their wellbeing and would not tolerate anything that appears exploitative or uncaring. We banned lab chimps a while ago and a good zoo is a huge improvement on what they had.