They had no idea what was wrong.

The patient, a 41-year-old female, lay on the kitchen floor unresponsive. Her husband said that she’d collapsed suddenly while complaining of a headache. Immediately, the two paramedics began their assessment. At least she was breathing and had a pulse.

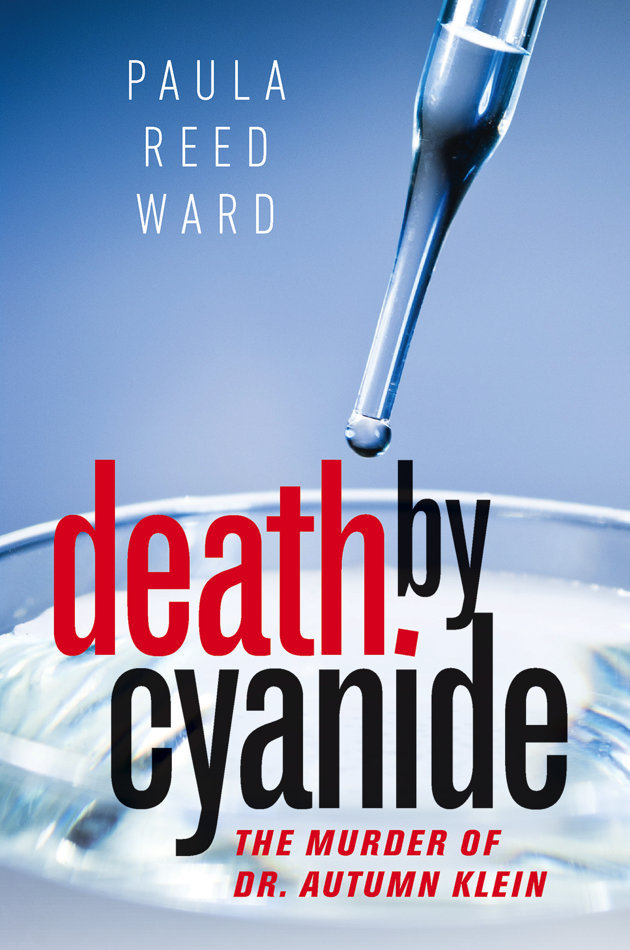

The accompanying article is excerpted from Paula Reed Ward’s new book “Death by Cyanide: The Murder of Dr. Autumn Klein,” published this month by ForeEdge, an imprint of the University Press of New England.

Paramedic Steve Mason got a quick summary from the husband Robert Ferrante. He said his wife Autumn Klein was a neurologist at the University of Pittsburgh-Medical Center. She had returned home at about 11:30 p.m. after a grueling day at work and tumbled to the floor just a few minutes later. Mason asked him about a big Ziploc bag of white powder on the kitchen counter. It was Creatine, Ferrante said; his wife was taking it for infertility. As they spoke, Mason’s partner Jerad Albaugh got his attention.

Their patient was crashing. Her blood pressure and pulse were dropping fast.

“She’s not responding,” Albaugh said.

The men loaded the unconscious woman onto a gurney and rushed her to their ambulance, parked in front of the home. They called ahead to the hospital and raced the half mile there, with Albaugh unable to do anything other than start an IV during the short trip.

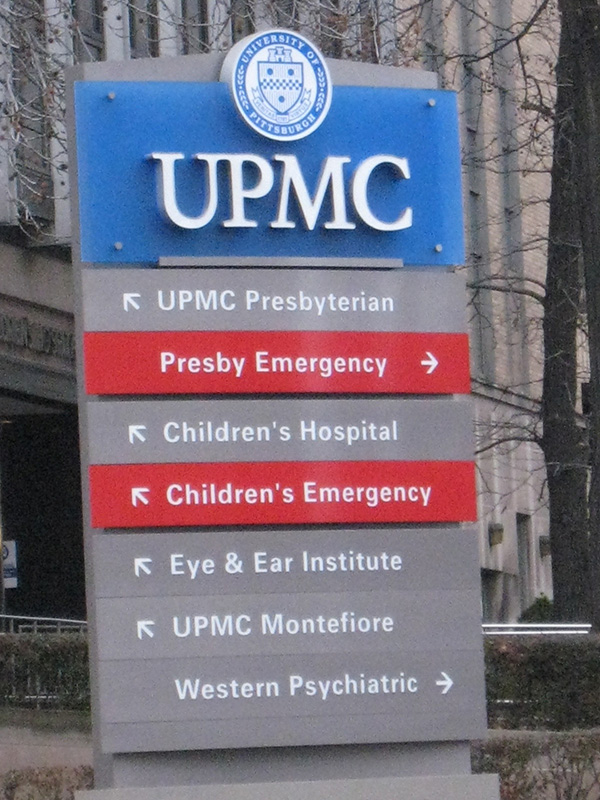

They pulled up to the emergency entrance of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center-Presbyterian hospital — called Presby by local residents — at 12:21 a.m. Just over an hour after she had left work there, Klein lay prone on the gurney, her arms contorted and her face twisted up and over her left shoulder.

Emergency department resident Dr. Andrew Farkas met the stretcher in the hallway. Klein’s eyes were open and glassy, and her breaths were shallow. There was a vacant look on her face.

They rushed her to curtain area 32 in the emergency department. Her heart rate was measured in the low 40s, and her blood pressure was a mere 48 over 36. Although her pupils were reactive to light, the patient — whom they now knew was one of their own — was unresponsive.

The team of nurses and technicians assisting Farkas put in another IV to push fluids and boost Klein’s blood pressure. Her respirations were starting to slow — as low as four per minute — and Farkas knew she needed to be put on a ventilator immediately to help her breathe. He inserted the breathing tube into her mouth and down her trachea, then ran to get his attending physician, Dr. Thomas Martin.

Just two minutes after Farkas checked his patient’s pupils, Martin checked them again. They were no longer reacting to light.

Farkas had ordered a broad panel of blood tests, gases, and chemistries be sent out to check Klein’s organ function. The problem, though, was that because she was so slim, the staff was having trouble getting a blood draw from her arm. Using a larger needle, they moved to the femoral artery in her leg, but still couldn’t successfully take her blood.

Just over an hour after she had left work at the hospital, Klein lay prone on a gurney, her arms contorted and her face twisted up and over her left shoulder.

Visual: WikiMedia

As the staff continued to work on Klein, Ferrante arrived with his friend and colleague Dr. Robert Friedlander, who had driven him there. Like his wife, Ferrante, 64, was also connected to Presby; he was co-director of the Center for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Research at the University of Pittsburgh’s Medical Center.

Farkas pulled back the curtain surrounding the bed where Klein lay, the vent pushing air in and out of her lungs. Ferrante took a long look and then screamed, “No!”

Farkas continued his assessment while he listened to Ferrante describe what had happened at the house. Klein had been complaining of headaches in recent weeks, he said, and when she arrived home from work that night she’d complained of not feeling well. He said she grasped her head in her hands and then dropped to the floor.

Farkas and Martin now suspected she was having a brain hemorrhage. They needed to get a CT scan of her head immediately, so they momentarily scrapped their plans for the blood draw to move her to the 3-D imaging machine. It was only one hundred feet from her bed, but Klein’s blood pressure was below 60, and her pulse was in the 30s. Just putting her in the scanner was too risky. Ignoring protocol, Martin went in with her. Draped in a protective vest, he pushed epinephrine every one to two minutes to keep her heart pumping.

As the scan ran, the images immediately appeared on a computer monitor in the control room.

They were normal.

“It looks completely clear,” Farkas said. “There’s no explanation for her symptoms. There’s no evidence of any disease state whatsoever.”

The emergency team then switched focus, trying to think of what else could cause such a dramatic decline so fast. They ordered additional CT scans of Klein’s chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Her EKG showed no abnormalities in her heart’s electrical activity. There was no aneurysm in her abdomen. She had no aortic tear that could have caused blood to spill into her chest cavity. There was no blood clot in her lungs.

The treatment team had no idea what was wrong.

At 1:20 a.m., Martin paged the hospital’s on-call intensivist — a doctor who specializes in treating critically-ill patients. Dr. Lori Shutter returned the page.

“This is Tom Martin. I’m one of the ED docs.”

“Yeah,” Shutter answered. “What do you need?”

“I have a patient down here. You may have heard of her: Autumn Klein. She’s one of our neurology attendings.”

“Autumn?” Shutter responded. Klein, who was chief of the division of women’s neurology at the hospital, was her colleague, neighbor, and friend.

“Yeah. She got here around midnight. I’ve been working on her since then, and I just need help. I don’t know what’s going on.”

Shutter hung up the phone, thinking to herself, “What the fuck would have happened to Autumn? She’s younger than me. What could have happened?” She rushed to the elevators to make the trip down the 9 floors to the ground level of the hospital and hurried around the corner to the trauma room where Klein lay, a huge team of nurses, technicians, and doctors working on her. Ferrante, Friedlander, and Klein’s neurology chair Dr. Lawrence Wechsler, were there as well.

“Bob, what’s going on?” Shutter asked Ferrante. He said again that his wife had collapsed at home.

Martin was at the bedside, still pushing syringes full of epinephrine to try to sustain blood pressure. He told Shutter about Klein’s condition, the need to intubate her, and the puzzling fact that all the CT scans were clear.

“I can’t figure out what’s happening.”

The nurses were still having difficulty getting blood from Klein, who at nearly 5 feet 7 inches, weighed only 107 pounds. Everyone agreed she needed to have a central line so that they could more quickly administer medications and draw blood.

Using an ultrasound to locate the patient’s internal jugular vein — the largest in the neck — Farkas inserted a triple-lumen catheter. As he placed the tube inside the vein, the blood that came out was bright red — noticeably so, since venous blood, which has less oxygen in it, should be much darker.

The resident alerted Martin to what he’d seen, wondering if he’d accidentally placed the line in an artery, where the blood would be a much brighter red. But the more experienced physician had seen the ultrasound and knew the catheter was in the right location. Still, Farkas did a manometer test, placing a plastic tube over the needle to see what would happen to the blood inside. If it pulsed up, then the line was in an artery. If it dropped down, then it was in a vein. When Farkas held the line up, Klein’s blood dropped back down. They had definitely tapped a vein; Farkas deftly stitched the catheter in place.

The treatment team, which now included a neurologist, a cardiologist, and an intensive-care-unit physician, had received Klein’s initial lab results, looking at her electrolytes, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, red blood cell volume, and coagulation factors. Again, they were normal. The only things that came back abnormal were the patient’s pH and oxygen levels. There was a lot of acid in her blood, indicating a severe metabolic dysfunction, and her oxygen levels were more than double what they should have been. Klein’s cells were unable to use the oxygen in her blood, but the doctors didn’t know why.

They continued to give her sodium bicarbonate to lower the acid levels and increased the ventilator speed to make her breathe faster. They were also still pushing huge doses of epinephrine regularly.

“We’ve been doing this a long time,” Martin said. “We need to come up with some ideas.”

Shutter suggested running a toxicology screen that would check for a standard set of drugs and poisons. As the team was treating Klein, they heard her husband talking about her.

“She really enjoyed what she was doing,” Ferrante said. “She loved her job, and she would never want to survive if she couldn’t be herself and continue her work.”

At 2:17 a.m., as the physicians continued to try to stabilize her, Klein went into cardiac arrest. They called a code. A respiratory therapist disconnected the ventilator and began bagging her manually as a team of technicians and nurses took turns performing chest compressions. Each person got up on top of Klein, straddling her. They clasped their hands one over the other with arms fully extended, pounding on her chest to try to compress it one to two inches with each pump.

Martin had his hand on Klein’s femoral artery in her groin to ensure her blood was still circulating with each compression.

“Shit. Bloody secretions,” Martin exclaimed as he saw bloody fluid coming up from the breathing tube. They suspected her ribs had been broken from the compressions and maybe punctured her lungs.

For 22 minutes, they took turns performing CPR, continuing to push epinephrine to try to sustain her heart and blood pressure.

“This has been going a long time,” Martin said. “This isn’t going well. Do you think we should call this?”

“We probably should, but I’m not going to be the one to go out and tell the husband,” Shutter responded. She told Martin she couldn’t tell Ferrante they had let his wife die. “Do you mind going out to talk to him?”

Shutter took over running the code as Martin went to speak to Bob. He sobbed at the news.

She replaced Martin in feeling for Klein’s femoral pulse and was struck for the first time by how small the woman was, lying on the bed wearing nothing but a pair of pink, animal-print panties.

“No one should ever be in this position with a friend of theirs,” Shutter thought, a wave of despair flashing through her as she looked at her hand in her friend’s groin. Just as quickly, though, she told herself to stop staring.

“The next round is when we’ll stop if she’s not back,” she told the team.

They gave Klein another round of epinephrine and started a last set of compressions. About 30 seconds in, Martin returned to the room.

“Her husband understands we’re going to call it,” he said.

A short time later, a nurse keeping track of the time announced, “It’s been two minutes.”

Everyone stopped what they were doing.

“Oh, my gosh, there’s a pulse,” Shutter said. “Someone confirm.” A touch to Klein’s carotid artery confirmed.

Her heart was beating — not well, but like a quivering bag.

Using electric paddles, they shocked the heart with 120 joules — which Shutter compared to being hit in the chest with a baseball thrown at 50 miles per hour.

The shock steadied the heart rate, though it remained very slow. She was not conscious or responsive. But she was alive.

“Now what do we do?” Shutter asked. “What’s the next step?”

The treatment team knew they needed to take measures to ensure Klein’s heart continued beating, and so they paged the on-call cardiothoracic surgeon. As the physicians discussed their ideas, at about 3 a.m., Friedlander suggested he and Ferrante go get a cup of coffee.

When the cardiothoracic surgeon and his fellow arrived, they discussed a few different options, including placing Klein on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO which removes blood from the body, filters and puts oxygen in it, and then returns it so the organs can use the oxygenated blood to continue to function. They also considered installing an intra-aortic balloon pump.

The physicians worried that, because of their patient’s small frame, they would not be able to place the ECMO lines. The tubing for the procedure is the size of a small garden hose and must be pushed several inches into the patient’s veins and arteries.

Dr. Jay Bhama decided they should do the balloon pump, but as they made their plans — and discussed whether Klein could sustain a trip to the cardiac catheterization lab — her vitals again began to fall.

“While you guys are standing there, we’re losing her blood pressure,” said Dr. Jeremiah Hayanga, who was working with Bhama that night.

They immediately decided they had to go with ECMO. The physicians knew it was possible that Klein could lose her limbs from the procedure because they would not get proper blood flow with the large lines inside of her.

But without it, they knew, she would die.

There was no time to get to an operating room, so the doctors called the emergency ECMO team on the hospital’s second floor, telling the perfusionist to bring all of the equipment directly to the emergency department. Within minutes, the team wheeled the 18-inch-wide, 36-inch-tall machine to Klein’s bedside.

Hayanga and Bhama worked together. They prepped both the right and left femoral regions. Using a scalpel, they nicked the skin on each side, and then used a dilator catheter to widen the holes to accommodate the width of the tubes. Once they were big enough, they fed an 11-inch-long plastic tube up into the femoral vein on the left and into the femoral artery on the right. When they turned on the ECMO machine, it would work by drawing the blood out of the femoral vein, running it through the filtration and oxygenation system, and then return it to Klein’s body through her right femoral artery.

They then stitched the tubes into place.

Once Klein was on ECMO, the staff was able to maintain her heart rate at 60 to 70 beats per minute. They gave her a transfusion of two units of packed red blood cells and planned to cool her body because hypothermia can help recovery after cardiac arrest. However, doctors noted that she was already four degrees cooler than the 33 degrees Celsius that is recommended.

When Ferrante and Friedlander returned to the emergency room 30 minutes after they’d left, they learned Klein was on ECMO.

Ferrante appeared to relax at the news, and Martin worried that he’d given the man false hope. Although her heart was beating, Klein’s condition remained grave.

Throughout the night, the physicians talked about what they thought might have caused their colleague’s collapse. They suggested a number of ideas, including Brugada syndrome, which is an abnormal heart rhythm, and even the possibility of an electrical brain storm, which is when brain cells fail to properly discharge energy, causing a surge of it through the brain.

They consulted local, national, and international experts to try to get the best information possible to guide her care.

At 5:30 a.m., it was agreed that Klein could be moved from the emergency department to the cardiothoracic intensive-care unit (CTICU) on the second floor of the hospital. On arrival, the staff removed Klein’s white-gold wedding band to return to her husband and hooked her up to a continuous EEG machine with 32 small electrodes placed around the head to measure her brain activity. There was none.

Dr. Frank Guyette, a consultant with the hospital’s post–cardiac arrest team who evaluated Klein at 8:21 a.m., noted that her blood pressure was still just 70 over 30. Her pupils were not responding to light. She had no gag reflex. Her extremities showed no spontaneous movement, and there was no response to painful stimuli. He put her chances of a meaningful recovery at less than 4 percent.

Robert Ferrante was found guilty of the murder of Autumn Klein in 2014.

Later that morning, Dr. Jon Rittenberger, another member of the post–cardiac arrest team at Presby, took over Klein’s care. He noted that she was “profoundly comatose” with a “flat, nonresponsive EEG,” but said that from a “neuro-prognostic standpoint, it is simply too early to tell.”

The doctors treating Klein agreed that it would not be fair to fully assess her brain activity until she had been properly rewarmed since the cooling protects brain function. Shutter spoke with a colleague at Yale, who suggested they give their patient at least 72 hours at average body temperature before reaching any conclusions. She passed that information along to Ferrante.

“Don’t call things too early,” she told him. “You never know.”

Rittenberger, still stumped by what had precipitated Klein’s collapse, called his colleague, Dr. Clifton Callaway, an emergency physician, who was traveling. He filled him in on the case and recounted the patient’s symptoms — including the bright-red blood in the central line— and noted that she still had very high levels of acid, even with improved blood flow and increased levels of oxygen.

Callaway suggested running a test for cyanide toxicity, even though the chances of that causing the collapse were slim.

“Please also note that due to her profound acidosis on initial arrival, we had added on a toxicologic screen along with serum alcohols and cyanide (although this is unlikely),” Rittenberger wrote in Klein’s chart. The blood was drawn at 2:32 p.m. on April 18, and the tube sent to Quest Diagnostics in Chantilly, Virginia, to be tested.

About two hours later, Ferrante met with a social worker at the hospital. He told the woman that his wife’s parents had arrived in Pittsburgh from their home in Baltimore, but that he had not talked to them and was uncertain if they planned to visit their daughter.

Lois and Bill Klein had driven through the night from their home in Towson, Maryland, after receiving a call from Ferrante. He told them he did not want to take them to see their daughter until his adult children (from a previous marriage), Michael and Kimberly, arrived from Boston and San Diego. Until then, the Kleins remained at the couple’s house with Ferrante and he and his wife’s six-year-old daughter, Cianna.

That evening, though, the adults gathered together and finally went to the hospital.

When the group entered Klein’s room in the cardiac intensive care unit, her grave condition was obvious.

Over the next two days, Klein’s family members spent their time shuttling back and forth from the couple’s home to the hospital. Lois and Bill sat for hours at a time at the bedside. But they were increasingly unhappy with the situation. They felt like they were being left out of the discussions about their daughter’s care and condition. When Bob Ferrante met with his wife’s doctors, he would include Kimberly, who was a physician, but not the Kleins. Finally, when Ferrante met with the doctors in the hallway, his mother-in-law started forcing her way into the conversations, determined not to be left out.

She was then frustrated by her son-in-law’s behavior during the discussions with the doctors. Instead of letting them talk about their suspicions, Bob kept making his own diagnoses.

“Don’t you think this is what it is?” he would ask.

The team of physicians continued to talk about what might have caused such a drastic, untreatable condition. Klein had been in touch with her family physician six weeks earlier, noting that she had been having significant hair loss and that she thought she might need to have her hormone levels checked, but otherwise, there were no medical complaints reported.

At the hospital, Ferrante told several people he believed his wife had suffered an electrical brain surge.

“Autumn’s two-year history of headache-migraine may have caused this,” he wrote in an e-mail to Friedlander on April 20. “While we were certain of four events that I witnessed, there may have been more that she did not discuss or were subclinical. There remains the hypothesis that this was myogenic and that there was a defect in the heart.”

As it became clear that Klein was not going to recover, the family started talking about her wish to be an organ donor. Intensive-care physicians treating her believed that the liver and kidneys could be transplanted.

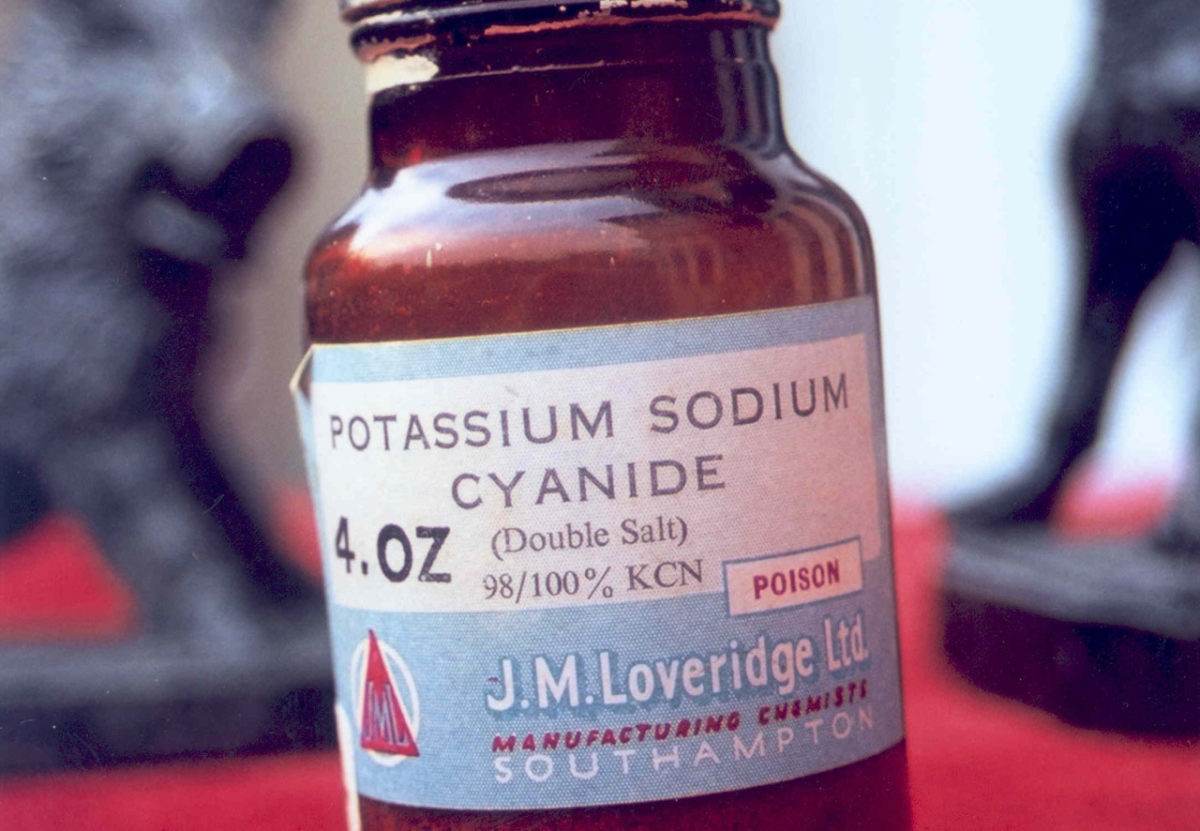

Two days before Klein’s collapse, police later found, Ferrante had a staff member order a bottle of cyanide like this one.

Visual: Wikimedia

Ferrante e-mailed Friedlander: “This may be the last physical gift that she can provide and would be a wonderful one.”

There was also talk about an autopsy.

Rittenberger suggested to Ferrante that if his wife had died from a heart-rhythm disturbance, then an autopsy ought to be performed. It was likely that such a condition would be genetic, which meant their young daughter could be at risk.

Lois Klein also wanted an autopsy. She wanted to know what had happened. “A healthy 41-year-old woman doesn’t just come home, drop on the floor, and die,” she said.

But Ferrante said no. He was so insistently against the procedure that several physicians noted his rejections in Klein’s chart. He didn’t even want a limited one — an external examination and toxicology screening — that would have allowed for genetic testing. He talked to Shutter about it, suggesting that the ECMO might wash anything out of his wife’s system that would point to cause of death.

“What would an autopsy tell us?” he asked.

He reiterated the point in the e-mail to Friedlander: “Discussion with all the principals suggests that autopsy, limited or full, will not resolve this issue.”

However, in Pennsylvania, with any unnatural death, the law requires an autopsy. Whether Ferrante wanted it or not, the Allegheny County Medical Examiner’s Office was going to do one.

As Klein entered her third day in the hospital, her status remained unchanged.

“Autumn’s EEG remains without any activity and has been so twenty-four hours after rewarming. The ICU team is ready to call her death,” Ferrante wrote to Friedlander. “The fact that the EEG has not change[d] suggests little chance of recovery. Bedside brainstem exam is negative. It would be wonderful to get another CT but they are unable to take her off ECMO to do this. Unclear whether her heart would sustain the workload.”

Ferrante took Cianna to the hospital to see her mother Saturday morning. For the two previous days he had sent his daughter to school to try to sustain normalcy, telling her that her mother had gone away to a meeting but would return soon. By Saturday, though, he explained to his little girl that her mom had a medical problem, was very ill, and was in the hospital.

“Cianna was there all morning,” Bob wrote in his e-mail to Friedlander. “That was the best thing to do. She was pleased to see her mom, but when she left she commented that she did not think that mommy would be coming back home. This is all so very sad to me. It breaks my heart.”

Ferrante agreed that day to remove Klein from life support.

At 11:06 a.m. on April 20, Rittenberger performed the first of two required brain-death exams on Klein with her parents and Ferrante at her side. He called to her, announcing his presence. She did not respond. He pinched her. There was nothing. He checked her pupils, shining a light directly into her eyes. No response.

No gag reflex.

A doll’s-eye reflex — where the patient’s eyes spontaneously move to the side when the head is moved in the opposite direction — was absent.

And Klein showed no reaction when he dripped cold water into her ear canal.

At 12:10 p.m., he declared her brain dead.

Fifteen minutes later, Dr. Joseph Darby, a critical-care physician, conducted the same tests with the patient’s parents at her bedside.

He also took Klein off the ventilator for a full 5 minutes. “Throughout the entirety of my observations to my examination, I observed no respiratory efforts whatsoever,” he wrote.

Klein was pronounced dead at 12:31 p.m. on April 20, but remained on the equipment to keep her heart beating and her lungs functioning in order to facilitate organ donation.

That afternoon, staff from the Center for Organ Recovery and Education met with Ferrante to obtain permission for organ donation. The family remained with Klein throughout the evening.

Then, at 2:26 a.m. on April 21, staff arrived in the room to prep her for organ harvesting, and she was transported to the operating room.

The surgery began at 3 a.m. and ended two hours later.

Her body arrived at the medical examiner’s office six hours after that.

Paula Reed Ward has been a reporter with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette since 2003. Scenes and dialog in the foregoing excerpt have been recreated based on extensive examination of medical records, emails, court documents, and interviews with the parties involved.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

4 months before his wife’s death he googled “cyanide poisoning”

2 months before he googled “divorce Pittsburgh pa”

2 weeks before he googled “does increased vaginal size suggest wife is having sex with another?”

Days after her death searches were found for

potassium cyanide

Detecting cyanide

Cyanide creatine

Leading to searches such as – “how would a coroner detect if someone is poisoned by cyanide?” These searches were done the same day investigators questioned Ferrante.

In the fall of 2014 the trial began, the defense was able to bring Cyril Wecht to the stand to testify that he could not definitively say that she died from cyanide. His findings were based on the quantitative test the NMS performed showing that Autumn had a normal level of cyanide in her system. The scientific argument here is that cyanide leaves blood quickly and that the test done by NMS was done 18 days after being collected which would be plenty of time for the cyanide to no longer show.

Verdict.. I think this is pretty clear to any of you who think this evil man didn’t kill his wife he’s pushing for her to take the creatine which doesn’t even help with fertility he has a bottle that he just ordered it’s opened and then all this searching on his computer you’ve got to be absolutely idiotic to believe he didn’t kill his wife wake up

read comments

She did not die of cyanide poisoning…how can jurors be so stupid? Because of his research on his computer…If a test is wrong, it’s wrong. If she had died of cyanide…she would have died immediately…not hung on for days with no symptoms of poisoning except the blood issue which can be caused by heart issues….but because he researched cyanide and ordered cyanide…he was convicted…

What a waste of humanity…what stupid jurors….how can something so simple not be apparent to them at trial….they wanted someone to pay…so he is paying….what a waste…why did the judge not order independent testing? Because our stupid legal system won’t allow it…what a waste.

Bravo, Cathie. You are exactly right. No cyanosis, no swift death, no lung frothing, and no futile resuscitation efforts. (In the ambulance, she has actually revived quite easily, a feat impossible with cyanide poisoning.) May this poor man get a chance at relief through a post-conviction act filing. I blame the Medical Examiner for not realizing the facts do not fit together.

Cyanide poisoning does not cause cyanosis (blue palor). Just the opposite. Cyanide stops cells from using oxygen, so venous blood is bright red. Cells resort to lactic acid fermentation, so acidosis. (this is bio 101 stuff people!) The highest demand organs are brain (headaches) and heart (heart failure). The medical signs match cyanide poisoning!

So you admit that CN deprives the body of oxygen? Good. So you know that once CN is in the bloodstream NO OXYGEN IS AVAILABLE to the heart and other organs. Right? So why was she so easily resuscitated? Cyanosis is only absent when the victim dies quickly or when the dose is very low. Neither of these facts apply to Autumn Klein. Supposedly, the amount of CN detected by Quest was lethal, at 15hrs after consumption, yet she lived for 3 days. Logically, cyanide must not have been present at all. They imprisoned an innocent man.

Concluding that cyanide poisoning caused death from the presence of “acidosis” is like concluding someone has HIV from observing them sneeze.

Autumn Klein was diagnosed with a mitochondrial disorder while she was still alive, and she experienced migraines and auras in the weeks before she died. For those who think her collapse could be nothing but cyanide, please read this description of mitochondrial disease symptoms: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/mitochondrial-encephalomyopathy-lactic-acidosis-and-stroke-like-episodes

“Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) is a condition that affects many of the body’s systems, particularly the brain and nervous system (encephalo-) and muscles (myopathy). The signs and symptoms of this disorder most often appear in childhood following a period of normal development, although they can begin at any age. Early symptoms may include muscle weakness and pain, recurrent headaches, loss of appetite, vomiting, and seizures. Most affected individuals experience stroke-like episodes beginning before age 40. These episodes often involve temporary muscle weakness on one side of the body (hemiparesis), altered consciousness, vision abnormalities, seizures, and severe headaches resembling migraines. Repeated stroke-like episodes can progressively damage the brain, leading to vision loss, problems with movement, and a loss of intellectual function (dementia).

Most people with MELAS have a buildup of lactic acid in their bodies, a condition called lactic acidosis. Increased acidity in the blood can lead to vomiting, abdominal pain, extreme tiredness (fatigue), muscle weakness, and difficulty breathing. Less commonly, people with MELAS may experience involuntary muscle spasms (myoclonus), impaired muscle coordination (ataxia), hearing loss, heart and kidney problems, diabetes, and hormonal imbalances.

“Boctone Scientist” aka “Boston Scientist” seems to willfully ignore facts & the chronology.

At 11:18 pm on April 17, 2013, video surveillance established that Autumn Klein left her work at UPMC Presbyterian.

At 11:52 pm, Robert Ferrante placed a 911 call, stating that his wife had “just got home from work”, then collapsed, staring, breathing normally, and that these symptoms started “10 minutes, maximum”. During the 911 call, Autumn Klein could also be heard grunting & moaning in the background. The 911 call lasted 11 mins, 55 secs.

During the trial, several work colleagues testified that Robert Ferrante told them he prepared a drink for Autumn Klein with creatine in it, and she drank it before collapsing. In a text message exchange earlier that day, Autumn Klein wrote, “I have an aura. According to my calendar, I ovulate tomorrow.” Robert Ferrante replied, “Perfect timing. Creatine :0)” and “I’m serious. It will make a huge difference. I certain.”

When paramedics arrived, they found Autumn Klein lying on the kitchen floor next to a gallon-Ziploc bag of powder and a small glass vial on the kitchen counter. Robert Ferrante told paramedics the Ziploc contained creatine to help her with fertility.

While on the stand, Robert Ferrante denied that Autumn Klein ever drank anything when she arrived home.

After the paramedics rushed her to UPMC Presbyterian, Autumn Klein had a treatment team that included a neurologist, cardiologist & ICU physician. When all her other labs came back normal, her cardiologist ordered a toxicologic screen for cyanide due to “profound acidosis on initial arrival”, and her oxygen levels were in the five hundreds. B.S. conveniently ignores those lab results, as well as the undisputed fact that Klein’s cardiologist ran a toxicology screen for cyanide while she was still alive.

During the trial, three different tests were presented into evidence that confirmed cyanide was present. The two Quest lab test results reflected a fatal dose of cyanide (2.2 mg/L and 3.4 mg/L).

A conflicting NMS forensic lab test result reflected a background/non-fatal dose of cyanide (.5 mg/L). Notably, the NMS forensic lab test was paid for by the defense. The NMS test couldn’t be completed because a piece of equipment needed to examine the precise level of the poison in Klein’s blood wasn’t working and because the control came back negative, indicating that the test being used wasn’t reliable. Eventually, NMS did find a cyanide metabolite — a substance created when the poison is broken down in the bloodstream — but only the .5 mg/L level that could normally occur in a person’s blood.

It’s also an undisputed fact that Robert Ferrante ordered a bottle of potassium cyanide on April 15 for overnight delivery. It’s a further undisputed fact that Robert Ferrante’s fingerprint was found on the opened bottle of potassium cyanide & 8.3 grams were missing from the bottle.

None of Robert Ferrante’s research projects ever called for cyanide. His research assistant Jinho Kim, testified that the only time Ferrante mentioned cyanide for a project was after the bottle arrived on April 16. When the bottle arrived, Kim asked whether the bottle should be locked up, and Ferrante instructed Kim to store it under his bench. Kim further testified that the only time he saw the bottle again was after the police investigation, when the bottle was discovered in the lab refrigerator.

During trial & on the stand, Ferrante testified that he had never used cyanide for his research and that he ordered the cyanide was for a future project.

It’s also an undisputed fact that from January 2013 until days before Autumn Klein collapsed, Robert Ferrante’s personal MacBook had dozens of Google searches relating to cyanide and human toxicity, and how a medical examiner can find cyanide in a body. One of the searches typed into Yahoo Answers on his computer was, “How would a coroner detect when someone is killed by cyanide?” Other searches included “divorce in PA”, “this is what a heart attack feels like to a woman”, and one search on his computer was, “malice of forethought”. Malice aforethought is the legal standard of proof to establish a premeditated killing.

The only appropriate conclusion to this mountain of evidence is the guilty verdict & conviction, which were also confirmed after multiple appeals.

“Boctone Scientist” aka “Boston Scientist” seems to willfully ignore facts & the chronology.

At 11:18 pm on April 17, 2013, video surveillance established that Autumn Klein left her work at UPMC Presbyterian.

At 11:52 pm, Robert Ferrante placed a 911 call, stating that his wife had “just got home from work”, then collapsed, staring, breathing normally, and that these symptoms started “10 minutes, maximum”. During the 911 call, Autumn Klein could also be heard grunting & moaning in the background. The 911 call lasted 11 mins, 55 secs.

During the trial, several work colleagues testified that Robert Ferrante told them he prepared a drink for Autumn Klein with creatine in it, and she drank it before collapsing. In a text message exchange earlier that day, Autumn Klein wrote, “I have an aura. According to my calendar, I ovulate tomorrow.” Robert Ferrante replied, “Perfect timing. Creatine :0)” and “I’m serious. It will make a huge difference. I certain.”

When paramedics arrived, they found Autumn Klein lying on the kitchen floor next to a gallon-Ziploc bag of powder and a small glass vial on the kitchen counter. Robert Ferrante told paramedics the Ziploc contained creatine to help her with fertility.

While on the stand, Robert Ferrante denied that Autumn Klein ever drank anything when she arrived home.

After the paramedics rushed her to UPMC Presbyterian, Autumn Klein had a treatment team that included a neurologist, cardiologist & ICU physician. When all her other labs came back normal, her cardiologist ordered a toxicologic screen for cyanide due to “profound acidosis on initial arrival”, and her oxygen levels were in the five hundreds. B.S. conveniently ignores those lab results, as well as the undisputed fact that Klein’s cardiologist ran a toxicology screen for cyanide while she was still alive.

During the trial, three different tests were presented into evidence that confirmed cyanide was present. The two Quest lab test results reflected a fatal dose of cyanide (2.2 mg/L and 3.4 mg/L).

A conflicting NMS forensic lab test result reflected a background/non-fatal dose of cyanide (.5 mg/L). Notably, the NMS forensic lab test was paid for by the defense. The NMS test couldn’t be completed because a piece of equipment needed to examine the precise level of the poison in Klein’s blood wasn’t working and because the control came back negative, indicating that the test being used wasn’t reliable. Eventually, NMS did find a cyanide metabolite — a substance created when the poison is broken down in the bloodstream — but only the .5 mg/L level that could normally occur in a person’s blood.

It’s also an undisputed fact that Robert Ferrante ordered a bottle of potassium cyanide on April 15 for overnight delivery. It’s a further undisputed fact that Robert Ferrante’s fingerprint was found on the opened bottle of potassium cyanide & 8.3 grams were missing from the bottle.

None of Robert Ferrante’s research projects ever called for cyanide. His research assistant Jinho Kim, testified that the only time Ferrante mentioned cyanide for a project was after the bottle arrived on April 16. When the bottle arrived, Kim asked whether the bottle should be locked up, and Ferrante instructed Kim to store it under his bench. Kim further testified that the only time he saw the bottle again was after the police investigation begun, when the bottle was discovered in the lab refrigerator. As soon as he discovered the bottle had moved, he notified lab administrators, who reported the incident to university police.

During trial & on the stand, Ferrante testified that he had never used cyanide for his research and that he ordered the cyanide for a future project.

It’s also an undisputed fact that from January 2013 until days before Autumn Klein collapsed, Robert Ferrante’s personal MacBook had dozens of Google searches relating to cyanide and human toxicity, and how a medical examiner can find cyanide in a body. One of the searches typed into Yahoo Answers on his computer was, “How would a coroner detect when someone is killed by cyanide?” Other searches included “divorce in PA”, “this is what a heart attack feels like to a woman”, and one search on his computer was, “malice of forethought”. Malice aforethought is the legal standard of proof to establish a premeditated killing.

The only appropriate conclusion to this mountain of evidence is the guilty verdict & conviction, which were also confirmed after multiple appeals.

Let me do the math for you: The sample that tested positive was drawn at 14:40, just over 15hrs after supposed ingestion. At a half-life of 10mins, that calculates to 90 half-lives. At T1/2 =30mins, the 30 half-lives would have elapsed. The level measured was 2.2mg/L. So 2.2mg to the power of 30 calculates to ~18 metric tonnes per liter. See? The math is absurd. The timeline is inconsistent with the known pharmacology of cyanide.

It is amazing how facts get twisted. Quest only performed ONE test. They did a math error the first time and got the higher value, but adjusted the math and got 2.2mg/L. This was from the same test, the same sample. A second sample, drawn 40mins after the Quest sample, was sent to NMS, and this test measured NEGATIVE for thiocyanate. Your statement about how to interpret their data is erroneous. It means “below detection,” i.e. negative.

So you either have to accept (1) that the Quest reading was actual cyanide CN- and thus conclude Autumn Klein consumed several metric tonnes of it (absurd), or (2) Quest measured thiocyanate, SCN- the metabolite, even though only 40mins later, NMS measured none of it, or (c) Quest measured something else.

That something else is malondialdehyde, a by-product of heart and kidney failure known as the “TBARS response.” This is the same false positive behind the Urooj Khan case, and others.

Your comments about the NMS sample and testing are wrong. The first time the sample was run, the positive control failed, so they threw out the results. The SAME sample was re-run two weeks later (after an instrument delay), and was run successfully, showing NEGATIVE for thiocyanate. According to standard procedures, a sample is stable in the freezer for 6months. The NMS data is completely valid.

It is the Quest test that is suspect. Unlike NMS, who run LC/MS, Quest uses a decades-old method based on a multi-step colorimetric reaction. Malondialdehyde cross-links the reagents, short-circuiting the chemistry that otherwise can be catalyzed by cyanide. Mayo Clinic declared this “pyridine-barbiturate” method to be obsolete.

You are absolutely off base. She had just about every symptom of cyanide poisoning one could have. Headache, dizziness, a few others followed by cardiac arrest, loss of consciousness, low blood pressure, slow heart rate, and seizures. The latter of the symptoms will start a few minutes after ingestion which is exactly what happened here. Remember? There was a bag of powder on the counter where she had been standing. Depending on the amount ingested, will determine how long it takes till your completely braindead. She was able to receive life saving treatment quickly, and this allowed her body to continue functioning even if her brain wasn’t functioning. Also, bright red blood from a vein most likely means the blood is acidic. Abnormal oxygen and acid levels in the blood are an indicator of cyanide poisoning, which happened with her as well. Lastly, all of the things I’ve said here along with a positive result on her toxicological screening means she died of cyanide toxicity! I know this because I work in the medical field and have had years and years of training. I don’t see how you can responsibly say it’s not cyanide toxicity if you don’t know anything about it.

You need to look up the symptoms of cyanide. They are: mouth frothing, cyanosis on face and extremities, blackened stomach, convulsions and swift death. Autumn Klein had NONE of these. NONE. A blood sample drawn soon after admittance was measured for thiocyanate, and it showed NEGATIVE. That means there was no cyanide. The sample sent to NMS (detected by LS/MS!) also returned NEGATIVE. Only the sample sent to Quest returned positive, and it was a colorimetric test, obsolete decades ago. The sample sent the Quest was drawn >15hrs after admittance. Cyanide has a half-life of 10-30mins, so no cyanide should be detected within a few hours, unless it kills you first. The mere fact that cyanide was detected so late in the timeline proves it was a false positive. Karl Williams, medical examiner, railroaded an innocent man. (This author Paula Reed Ward did a pretty good job at railroading, too.)

Cyanide kills by starving the blood cells of oxygen. No amount of resuscitation can help them, since it is not the lungs or heart that is the cause of the problem, but the blood. No cyanide poisoning victim ingesting a large amount of cyanide has ever survived in time to reach the hospital. Only a tiny few cases of people ingesting trace amounts (by air) who were rushed to hospital still conscious and administered with antidote, have ever been resuscitated. So please tell me, how did the paramedics who attended Autumn Klein, and who did NOT administer an antidote, resuscitate her so easily in the ambulance, given that she had taken a lethal dose? Isn’t it more likely she had heart failure?

“Headache, dizziness, a few others followed by cardiac arrest, loss of consciousness, low blood pressure, slow heart rate, and seizures.” – Actually, honey, these are just general symptoms that could apply to kidney failure, heart failure, alcohol poisoning and even paracetamol overdose. Hell, I have almost all those symptoms (except seizures) on a yearly basis from nothing. The symptoms of cyanide are very, very distinct. If you saw a cyanide poisoning victim, there would be no doubt about it. But there is plenty of doubt here. Try going to PubMed and looking up Case Reports of cyanide fatalities. You will see the symptoms do not match Autumn Klein at all.

Compare Autumn Klein’s death to this case: http://medind.nic.in/jbc/t12/i2/jbct12i2p104.pdf In this report, the victim inhaled a small quantity of cyanide (smaller than what Autumn Klein would have ingested, if it really were cyanide). This report describes cyanosis, lung frothing, and stomach blackening, together with swift death. Autumn Klein had none of these symptoms. Only metabolic acidosis is common to both, but acidosis is a general response, and can be induced by a wide range of factors. At trial, the prosecution expert said Autumn Klein’s symptoms could be consistent with very low dose of cyanide, but according to their diagnostics, she did not ingest a small quantity. Supposedly, she had a lethal concentration in her blood 15hrs later, so why, unlike ALL THE OTHER VICTIMS, did she not die quickly? Answer: Because cyanide was never present.

Does Paul Reed Ward deserve any blame for helping railroad this innocent man? She wrote fantasies about the Ferrante and Klein marriage, and made explicit statements about Robert Ferrante being a master manipulator. Almost certainly, these statements influenced the trial. She even repeats the lie that the sample that tested positive for cyanide was drawn soon after Autumn Klein was admitted to hospital. (In fact, this sample was drawn 15hrs later.) So, does Paul Reed Ward deserve blame for helping to convict an innocent man?

How saddening it is to see others rush to judgment based on their interpretation of behavior. Just wow! Meanwhile actual details indicate that Autumn Klein could not have died of cyanide poisoning. The pharmacology is wrong, and so are the presented medical symptoms. Funny how people can’t see the trees for the forest. She died of a heart attack, people! How obvious does it have to get? Symptoms match, timeline matches, diagnostics match – all except one, yet somehow the morons at the Medical Examiner’s Office believe that one outlier.

Sorry…but the guy is guilty. Insisting to not do an autopsy ? Serious red flags.. What if she had a genetic disorder that the daughter could get. Constantly interrupting others with his own diagnosis…the same thing? Ya…I’d be pretty suspicious of him too.

The symptoms are all wrong for cyanide because she never had any, exactly as you say! She was unconscious, and in the midst of a heart attack. Cyanide causes frothing at the mouth, convulsions, a dark red (cherry) color change to the face and hands, and most importantly, it causes quick death, with no possibility of resuscitation. Yet none of these things applied to Autumn Klein. None. The prosecution tried to dismiss their absence as being due to such a small amount of cyanide, but their own data do not support a “small amount.” Furthermore, the half-life is completely wrong. Quest supposedly measured 2.2mg/L cyanide 16 hrs after Autumn was admitted, including 8 hrs on dialysis. Cyanide is known to have a half-life of 10-30mins, after which it mostly decays to thiocyanate. You do the math! NMS measured zero thiocyanate. It is impossible. The pharmacology is completely wrong. Thirdly, Quest Diagnostics uses a colorimetric test that is almost identical to a “TBARS” test that measures products of heart and kidney failure. This is the source of the false positives for Urooj Khan, Mei Xiang Li, Janet Overton and others who all died without cyanide poisoning symptoms. Robert Ferrante is a wrongfully convicted man, railroaded by just about everybody. I hope one day the courts will look at the evidence properly.

“i have discovered.”? This implies that you were involved in the case, probably as one of the expert witnesses for the defense. If so, I would respect your opinion because must have significant medical and scientific qualification to be involved in the case. On the other hand, you also would tend to be at least somewhat biased toward your own interpretation. I am sure that the prosecution experts would say differently.

Like Will Rogers, all I know is what I read in the newspapers (well, and internet). But I don’t think the “symptoms” are “all wrong.” Technically, neither the the EMT’s nor the doctors at the hospital ever got the see the “symptoms” because symptoms are what the patient tells the doctor (or other health care providers). The only person who really knows the symptoms is her husband. She was unconscious when the EMT’s found her and she never regained consciousness. The totality of the medical “signs” and other objective evidence point to cyanide poisoning within the usual medical/biological uncertainty. The unusually bright red venous blood suggests that in itself. We rarely can be 100% sure about anything, but the story seems quite convincing for cyanide poisoning.

By the way, if a loved one of mine died mysteriously, I would demand an autopsy. Having the body cremated seems extraordinarily suspicious in itself. .

Clearly, Autumn Klein never died of cyanide poisoning. The symptoms are all wrong, the timeline inconsistent and the dosage impossible. This is a false positive, (one of five I have discovered) and Robert Ferrante is a wrongfully convicted man. This author’s newspaper articles did a lot to defame him and turn public sentiment against him, even though he was an innocent man caught in a family tragedy with zero history of unlawful behavior or even of a troubled personality. He spent his life dedicated to humanity, but the fantasies of journalists kicked him down anyway.