The Death of the National Children’s Study: What Went Wrong?

In the spring of 2009, researchers started showing up in the neighborhoods of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, clipboards in hand, to enroll expecting mothers and their unborn children in a huge environmental and health study that was going to last for decades. They asked probing questions whenever a woman answered the doorbell: Was she between the ages of 18 to 49? Was she pregnant, and if yes, how far along? If she wasn’t, could the researchers stay in touch with her until she knew she was having a baby?

The National Children’s Study (NCS), as it was called, had set out to enroll and follow 100,000 children from conception until the age of 21 in an effort to unlock some of our most enduring medical mysteries — from the prevalence of asthma and attention-deficit disorder to the rise of autism. Montgomery County, a bedroom community northwest of Philadelphia, was one of its test sites, and the women targeted for recruitment came from painstakingly selected households. They would answer dozens of questions about their own health, family medical histories, jobs, and personal habits. They would provide clippings of their hair and fingernails, and dust from their houses. When they went into labor, hospital staff would be on hand to sample cord blood, placenta, the infant’s first bowel movement, and other biological specimens — each a window into the prenatal chemical milieu.

Scientists, of course, knew that developing babies and young children are exquisitely sensitive to their environments. They just needed more data, more evidence, to connect early exposures to diseases and disorders later in life — and that’s precisely what the NCS, administered under the auspices of the National Institutes of Health, was going to provide: an unprecedented epidemiological portrait of the typical American home.

“We were tapping into a data goldmine,” said Jennifer Culhane, an epidemiologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia who was directing the study’s local efforts. “There was a sense that we were engaging in something special, and doing more to advance the science of pediatric disease than anyone else in the world.”

Those aspirations came to naught when the NCS was canceled in December 2014, after a 14-year history during which it burned through $1.3 billion in taxpayer dollars without generating much in the way of useful information. The study’s collapse barely registered with the national media, and unlike other major taxpayer-funded failures that have become political bludgeons on Capitol Hill, reaction in Washington has been muted. But the study’s collapse left a bitter legacy of anger and frustration among those who worked on the NCS for years, only to see their efforts wasted on a bungled enterprise that critics say went nowhere and accomplished nothing. Sources interviewed for this story gave a range of reasons for the study’s demise: deep scientific divisions over how it should have been carried out, partisan bickering, and even charges of deliberate dissembling over just how much such study would ultimately cost, to name just a few.

A National Children’s Study recruitment video from 2010, as presented by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

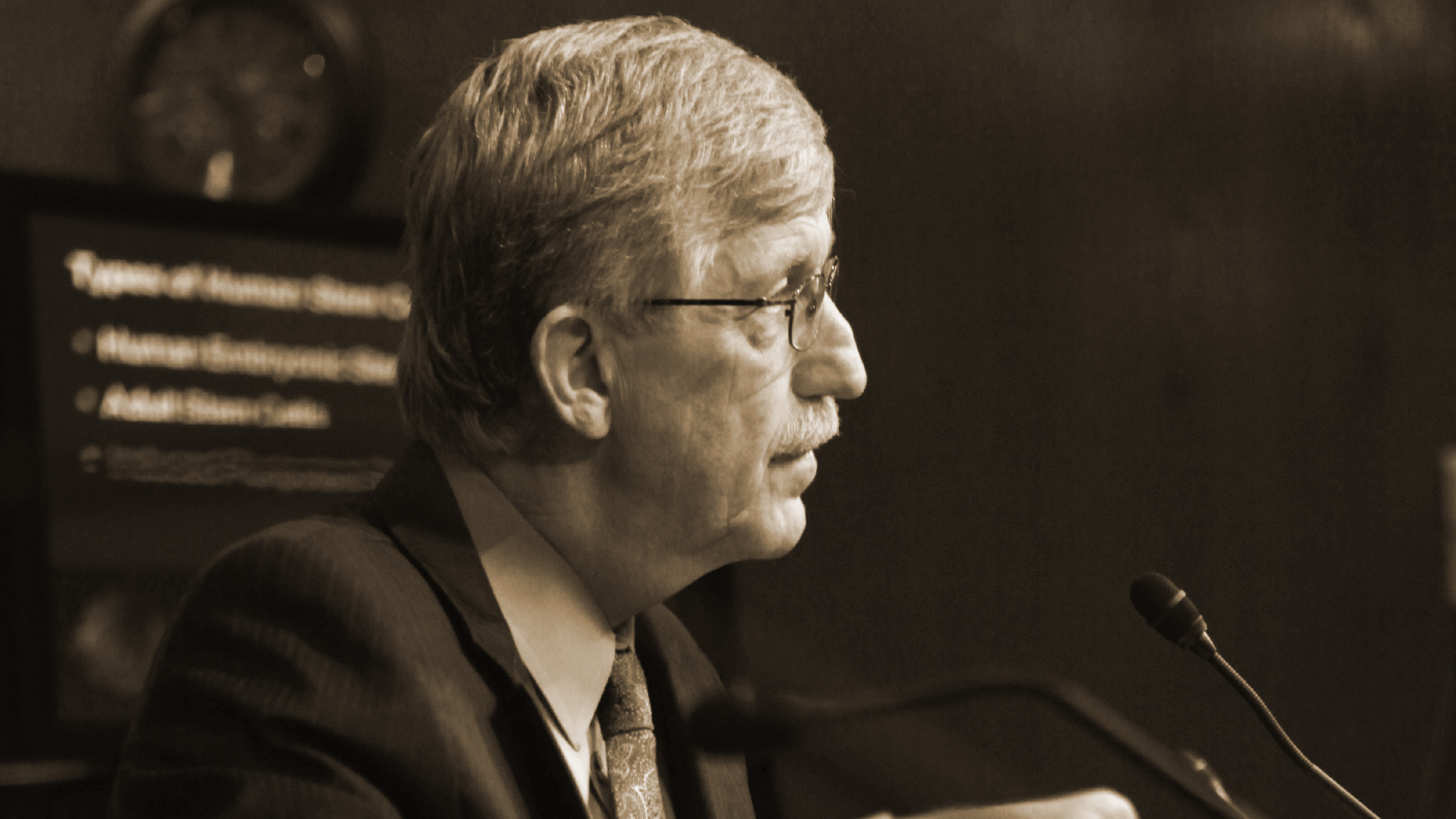

“There is no single factor that led to the failure of the NCS to achieve its goals, but rather a persistent set of challenges facing the design, management, and costs of the study,” said Francis Collins, director of the NIH, in an email message defending his decision to terminate the program.

Still, many critics say those challenges were a result of dysfunctional management, an ever-shifting set of objectives, and even lack of support at the highest levels of the National Institutes of Health.

“Too many people loaded this study with their own desires and wishes for what they wanted it to be without thinking enough about what it could actually achieve,” said Ellen Silbergeld, a former member of an NCS federal advisory committee and a professor of environmental science, epidemiology, and health policy at Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, in Baltimore, Maryland.

Many of the scientists who worked on the National Children’s Study have since moved on. But virtually all of the participants interviewed suggested that the American public lost a groundbreaking opportunity to answer questions about pediatric disease. Those questions remain as vexing now as when the study was launched nearly two decades ago — and Silbergeld was among many sources interviewed who lamented all the lost time and wasted money.

“This was a scientific humiliation for the United States,” she said.

The NCS was mandated by the Children’s Health Act of 2000 — one of the last bits of legislation signed by President Bill Clinton before being succeeded by George W. Bush. Congress drafted the law in response to mounting evidence that pregnancy and early childhood provided crucial windows into toxic vulnerability, and the act specifically called for a national study of environmental influences — physical, chemical, biological, and psychosocial — on child health and development. Most of the evidence suggesting the importance of understanding early exposures came from studies with experimental animals in the laboratory; available human studies were generally too small to generate statistically defensible conclusions. “What we needed was a human study that was both big in terms of the size of the population being sampled, and intense in terms of the amounts of data collected,” said Dean Baker, a professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, Irvine.

The National Children’s Study was designed to fulfill that need, and Peter Scheidt, a professor at the Children’s National Health System and at George Washington University was tapped as the project’s first director. Scheidt worked with an interagency coordinating committee of experts from throughout the federal government who were convened to plan, develop and implement the NCS, and he took an inclusive approach to managing the study, believing that no single person had the expertise needed to understand all its varied components.

At first, scientists were enthusiastic. “The more we considered the possibilities, the more excited we got,” Scheidt said in a recent interview. “What I found especially appealing was that we were combining multiple exposures and outcomes in one large research program, which to me was far more efficient than studying specific health problems individually.”

The good vibes that came with a big tent did not last long, and divisions quickly arose over how a truly representative cross-section of Americans should be developed, and even whether the NCS should recruit and follow women who weren’t pregnant yet but were expecting to be. Some experts, for example, felt that by including this so-called “preconception cohort” in the study, they could avoid missing key exposures occurring before newly pregnant women went for their first prenatal visits. Scheidt himself viewed the preconception cohort as a “unique first-time opportunity that was worth trying.”

Yet a sizable group of the study’s advisors and contractors considered it a misguided venture, especially since it would target young, highly mobile women who could be easily lost to follow-up. Even today, NCS veterans mock the preconception cohort as symbolic of the study’s excesses and failures. “Imagine knocking on someone’s door and then saying to them, ‘Hi, you don’t know me, but I represent the U.S. government. Are you thinking of getting pregnant?’” retorted Brenda Eskenazi, a professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Berkeley who was one of the study’s advisors. “How bizarre is that?”

In an email message, Scheidt insisted that preparations for the survey were much more nuanced than such criticisms suggest, and that extensive pre-visit communications were undertaken in targeted communities, in order to avoid any semblance of intrusion.

“After a campaign to inform the community, residents were first sent a letter informing about the study,” Scheidt said. “Then an appointment was made to discuss the study and further inform them. If those who were eligible indicated interest in participating, which most did, then they were asked about pregnancy status and likelihood of becoming pregnant. The approach was very careful and sensitive.”

NCS screeners who worked directly in the communities, however, suggest that those pre-emptive messages didn’t always hit the mark.

“Yes, there were community-based notifications about the study, and an advance letter was sent to all homes prior to the ‘door knock,’” said one researcher who ran a Vanguard site from the ground, and who asked not to be identified to avoid jeopardizing current employment. “But to tell you the truth, the vast majority of people initially approached in their homes did not remember seeing the advance card or ads in the neighborhood. And yes, this initial screening at the door included questions about the age of women in the home and pregnancy status.”

Researchers had also been debating how to design a study that wouldn’t miss potentially harmful environmental exposures among isolated groups of children — particularly minorities. Ensuring that the sampled population was demographically diverse enough to capture a broad range of minorities was paramount, but consensus on how to do that was elusive. One expert group made up of social scientists, geneticists, toxicologists and others, argued in favor of what’s called a “nationally representative sample.”

Considered the gold-standard in data collection, such a sample would give all children in the country an equal probability of being selected for the study — but it also posed huge logistical hurdles. To assemble such a sample, scientists would have to pore over census data to identify specific households that, in their aggregate, reflected the full diversity of children living in the United States. But since multiple households would have to be contacted for every successful enrollment, it was felt by some that meeting the 100,000-child target this way was impractical. No one had ever attempted household recruitment on such a massive scale, and concerns were raised over how time-consuming and expensive it might be.

Responding to the logistical hurdles, another group of mostly doctors and clinical researchers — including some who were already directing small birth cohort studies in different parts of the country — promoted an alternate method called “convenience sampling.” With this approach, NCS researchers would recruit from prenatal clinics located conveniently close to where they were already based. To the demographers, convenience sampling bordered on heresy. But to the clinicians, it promised greater efficiency. And since nearly all women go for at least one prenatal visit, they said, convenience sampling would still produce a cohort with enough diversity to meet the study’s statistical needs.

In 2003, the advisory committee voted almost unanimously in favor of nationally representative sampling, but the interagency coordinating committee continued to discuss the issue for several months. In June 2004, Duane Alexander, director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and Scheidt’s boss, polled the ICC. Half were for the representative sample and half were against it. Those in favor ultimately won the debate — a decision that Scheidt said took “two years and a million dollars” to reach, with considerable amounts paid to Westat, a survey research firm from Rockville, Maryland, which had been contracted to produce a detailed study of the various sampling options.

The study’s leadership announced that the NCS would go with nationally representative sampling for the pilot study in 2004, but in the coming years, efforts to generate that sample would prove to be as challenging as its opponents had predicted.

By this time, an NCS program office was already established at the NICHD, which soon began awarding contracts to seven academic “Vanguard Centers,” including Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), each of which were tasked with field-testing the various sampling protocols in advance of the main study. It was anticipated that when the main study got underway, it would contract out to 40 centers in total — the seven original Vanguard Centers and 33 others. CHOP won its first NCS contract for $13.7 million, in 2005, with Culhane later leading NCS activity there. (The hospital would ultimately win a combined total of nearly $45 million in NCS contracts, but the study was terminated before all of it was disbursed.)

Working with Westat, Culhane and her staff mapped out target recruitment areas, and then drove through them all, identifying households that might yield eligible women to enroll. They also held dozens of meetings with nurses, health officials, and community leaders, eventually developing relationships with 26 hospitals that would collect samples when recruits went into labor, and they worked tirelessly at community outreach. Countless hours and vast sums were spent to promote the study in local papers, on railways and in movie theaters. In many locations, outreach efforts persisted for up to a year and a half before any fieldwork got underway.

Meanwhile, the NCS program office and its advisors were working on a plan for assembling the national cohort. The research plan it finally released in 2007 was complicated, and in a nutshell called for recruiting from 110 county-based “sampling units,” or large groupings of households that, according to census information, were each expected to produce 1,000 births during a 4-year enrollment period. The sampling units were themselves distributed within 105 locations around the country, and enrollment would continue until the target recruitment of 100,000 children — including 25,000 enrolled into a preconception cohort — was reached. Importantly, the plan included hypotheses organized around 28 topic areas, and focused on outcomes such as neurodevelopment, behavior, asthma, and obesity. Nigel Paneth, a pediatrician and professor at Michigan State University, in East Lansing, who ran an NCS center called the Michigan Alliance, said the hypotheses were crucial because without them, the study would have been collecting data without planning statistically for the questions it hoped to answer.

Scheidt was determined to get external buy-in for the research plan and felt NCS had an obligation to go through rigorous peer review. He brought on board an expert panel at the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), chaired by Samuel Preston, a sociologist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania. But the assessment, published in 2008, proved to be a mixed bag. On the one hand, the panelists endorsed the nationally representative sample, the preconception cohort, and the inclusion of scientific hypotheses. On the other, the panel cited what it claimed were numerous shortcomings, including an inadequate pilot phase, too many outside contractors, and not enough attention paid to racial disparities, among other issues.

The panelists also acknowledged a major problem: funding uncertainties that Scheidt and others say stemmed from the Bush administration’s longstanding hostility towards the study. Congressional transcripts reveal the tension. During a senate appropriations subcommittee hearing on May 19, 2006, for example, Tom Harkin, the Iowa Democrat and a staunch supporter of the NCS, questioned Elias Zerhouni, the Bush-appointed NIH director at the time, and criticized what were apparently plans to eliminate the study the following year. “We just assumed, at least I did anyway, that [the NCS] was on track and that we were going to do it, and all of a sudden this year it pops up and it is going to be eliminated,” said Harkin, adding that he found the prospect of cancelling the study “very disturbing.”

Zerhouni, who didn’t appear willing to fight for the NCS, responded that the study simply didn’t match up with budget priorities. Given the need to fund other biomedical research commitments, “it was very hard to see how [the NCS] would fit in,” Zerhouni said.

The former NIH director did not respond to repeated requests for an interview, but sources involved in the development of the NCS say that it had been propped up for years with a zombie budget supplied by supporters like Harkin in Congress, and siphoned from operational funds appropriated for the NIH director’s office. Amounts varied unpredictably from year to year, making planning difficult, and exacerbating what were already worrisome delays. Completing the research plan had, in fact, been held up for two years because no one knew if reliable funding for the Vanguard Centers would materialize over the long-term. It had been eight years since the study had been launched, and not a single data point had been collected.

Everyone working on the NCS was hoping for more consistent, line-item support from the Obama administration after its arrival in 2009. But there was another problem: Scheidt and Alexander had severely underestimated the study’s lifetime expenses and they were keeping its ballooning costs under wraps. The initial projection, made in 2001 before the sampling plan was conceived, was just under $3 billion. As protocols were developed and financial realities set in, that number had climbed steadily, and by 2008, the projected budget for the National Children’s Study, including estimates for overhead and inflation adjustments, was topping $7 billion — much of it for data coordination, information management, and covering the decades-long expenses of maintaining a sample repository.

For his part, Scheidt said he was advised to stick publicly with the original estimate, even after he knew it to be false. “What was communicated to us was that we were not at liberty to change the projections from 2001 until there was more political flexibility,” he said. When the Obama administration took over in 2009, Scheidt and Alexander announced the much higher numbers, unleashing a furious response from Congress.

“There was this sense of outrage,” said Baker, who led an NCS pilot study. “Their supporters kept saying ‘We’ve been going to the mat for you all these years, and now you come out with figures like this?’”

A Senate appropriations committee report from the time criticized what it called this “lack of transparency” on the real costs of the NCS. “The Committee considers this withholding of information to be a serious breach of trust,” the report stated.

In a follow-up email, Scheidt suggested that the directive from budget officers was not made in writing, but that it was “very clear to Dr. Alexander that upward-revised budgets would not be acceptable, especially from 2006 to 2008, when the administration eliminated NCS funds in each proposed budget.”

But Lynn Goldman, dean of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University, and a long-standing NCS advisor, suggested in an interview that the leadership of NCS had been politically naïve in their handling of an increasingly unwieldy study and its soaring costs, though she added that she thought Scheidt had taken a fall for much bigger organizational and institutional problems. “I think that actually he has been scapegoated for something that’s more a symptom of dysfunction in NIH, [the budget office], and the relationship between the administration and Congress,” Goldman said.

In the summer of 2009, around the time that genomics pioneer Francis Collins was taking over as Obama’s new NIH director, Scheidt and his boss, Alexander, were fired. Steven Hirschfeld, a pediatrician with a Ph.D. in cell biology, then took over as acting director of NCS.

Hirschfeld, Goldman said, was no better — and in some ways worse.

It was at this point that the NCS saga began a new, and increasingly contentious second act. Hirschfeld declined repeated requests for an interview, or to respond to specific criticisms of his leadership by several sources interviewed for this story. By nearly all accounts, however, he brought a new and unwelcome style of management to the table.

Where Scheidt listened patiently to his advisors, Hirschfeld — who had held previous positions at the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration — marginalized them, and surrounded himself with junior-level staff. At one point, Nigel Paneth and four other scientists wrote a letter to Hirschfeld and the new NICHD director, Alan Guttmacher, in which they expressed their mounting frustrations with the National Children’s Study. In particular, they complained that virtually none of the program office staff had experience in perinatal epidemiology, longitudinal research, environmental health, statistical methods, or any of the health conditions mentioned in the Children’s Health Act.

The letter went unanswered, and Hirschfeld entrusted the NCS program office with developing new study designs that the project’s academic contractors — many of them internationally renowned in their fields — reacted poorly to. “There were constant attempts to change direction and focus,” said Eskenazi, the epidemiologist at the University of California, Berkeley. “The people in charge knew nothing about running birth cohort studies and they were very bad at listening to the people who did.”

In some instances, those changes addressed complex problems that the NCS increasingly had to contend with, even if Hirschfeld announced them in a blunt, non-emotive style that undermined his potential support. For instance, birth rates in the sampling units had proved lower than anticipated, and that was throwing timelines for the nationally representative sample into disarray. In response, Hirschfeld announced in late 2009 — only a few months after the Vanguard centers had finally gone into the field — that they would have to augment household-based recruitment with two additional strategies: an outreach campaign encouraging women to volunteer directly, and a “provider-based” approach that would enroll women from prenatal clinics located near the households that were otherwise being targeted door-to-door.

More disruptive changes followed in 2010. Without any prior consultation or discussion, Hirschfeld abandoned the scientific hypotheses spelled out in the research plan. Instead, he said, the NCS would develop into a pure data-gathering platform for investigating new hypotheses as the science evolved. The move angered some center directors, particular Paneth, who in an editorial for The Journal of the American Medical Association, later opined that abandoning the hypotheses was at the heart of the NCS’s failure. “When scientific questions do not drive the construction of the study,” he wrote, “the construction of the study defines and constrains the scientific questions the study can answer.”

Yet Hirschfeld’s move to abandon the hypotheses was supported by Obama’s NIH Director, Francis Collins, whom Vanguard Center directors believed was behind some of the program office’s more controversial decisions. Together with NICHD director Guttmacher, Hirschfeld and Collins co-authored an editorial for The New England Journal of Medicine, stating that while a core set of hypotheses had been developed initially, they now believed the study’s scope “should be limited only by scientific creativity, and not by current consensus priorities.”

Soon after dropping the hypotheses, Hirschfeld dropped Westat in its capacity as the study’s central data coordinating center. It was anticipated that data coordination alone, over the study’s lifetime, could reach over $800 million, and Hirschfeld was now introducing a more decentralized (and less costly) system with multiple organizations providing data coordination activities. He also tasked the research centers with more data collection and training duties, for which they were unprepared.

Randy Olsen, an economist and emeritus professor at Ohio State University, in Columbus, and a 3-year member of the NCS federal advisory committee, said that since the centers were mostly academic institutions, they were more accustomed to managing grants than contracts. As contractors, they had to comply with the federal government’s onerous requirements on data security, which meant they had to add staff and technical capacity that they didn’t previously have. “Complying with data security requirements ratcheted demands on the centers in a very costly way,” Olsen said. According to Paneth, the costs to his NCS center at Michigan State University totaled hundreds of thousands of dollars per year.

At the same time, federal advisors to the study suggested that they’d begun to feel increasingly alienated under Hirschfeld’s leadership. “We’d just sit there and have things thrown right past us,” said Silbergeld, who resigned her seat on the NCS Federal Advisory Committee in 2012, charging in an email to Collins that the goals of the study had been “significantly abrogated.”

“We were given nothing to prepare with and I found that really objectionable,” Silbergeld said in an interview. “It seemed at a certain point that relations between the program office and its advisors had become completely meaningless. We were supposed to act like tame house puppies — just wag our tails and do as we were told.”

The NCS program office ultimately determined that provider-based enrollment was more efficient, and abandoned the household strategy that had taken so many years to implement. But the program office staff struggled endlessly with how to make provider-based sampling representative. They were constantly revising sampling strategies, to the immense frustration of those who were out in the field. Hirschfeld faced angry reactions from directors of the seven initial Vanguard Centers, who thought he had given up on household recruitment too soon. “We had only been in the field since May, and by August, Hirschfeld was declaring household recruitment a failure,” Baker said. “But we hadn’t even gone into some of our neighborhoods yet.” (Baker would later co-author an editorial in The New England Journal of Medicine describing the NCS as being “plagued by lack of focus and poor leadership.”)

The final blow came when the program office announced in 2012 — the same year that Hirschfeld was made permanent director of the NCS — that in order to save costs and improve efficiency, it would dramatically shrink the number of research centers. Just four contract research firms would now be responsible for following the cohorts, putting significant distance between the scientists who would be managing the effort and the local populations. That also meant that the Vanguard Centers were losing contracts worth tens of millions of dollars, forcing them to lay off dozens of staff, and they were left in the position of having to explain it all to the women who had enthusiastically enrolled in the study.

“In essence, we had betrayed our communities,” Culhane said. “We had to tell them ‘Sorry, we’re packing up our marbles and going home and someone from out-of-state is going to be following your kids.” Olsen concurred: “When the Vanguards were dismantled, their staff were clearly heartbroken, disillusioned, and mad as hell. That generated a lot of ill will, and then people in the Vanguards wanted nothing more to do with the project.”

Taking note of the growing instability, Congress requested another review of the study by the National Academy of Sciences in 2013, but this time, the program office wasn’t ready. Where it had produced 750 pages for the 2007 panel review, Baker said, it could now only muster 56 pages, and crucial elements of the sampling plan were still being developed — a full 13 years after the study’s much-heralded inception.

Greg Duncan, an economist and professor at the University of California, Irvine, chaired the new NAS panel, which took stock of what it could. The panelists endorsed the study’s goals for representative sampling, and where the NAS in 2007 had backed the use of scientific hypotheses, the new panel supported the focus on data collection — “but we were very critical of how the study was being run,” Duncan said.

Duncan’s panel encouraged the program office to implement a different oversight process and to hire more experienced people. But NIH director Francis Collins had had enough. He convened a working group, and tasked it with assessing whether the NCS could feasibly meet its goals. When that group concluded that the answer was no, and that the program office should be dissolved, Collins terminated the study.

“The good news is the National Institutes of Health pulled the plug on a national children’s health study because it was fatally flawed,” opined Investor’s Business Daily upon news that the NCS had been axed. “The bad news is they wasted 10 years and $1.3 billion before they admitted it.”

Russ Altman, an internist and professor of bioengineering and genetics at Stanford University, chaired Collins’ working group. He said that in his view, it was inappropriate to concentrate so much power over the study at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The better approach, he said, would have been to run the study as cooperative research agreement, with the National Institutes of Health and academia forming an alliance to move it forward. “That’s certainly one of the big lessons,” he said.

Several sources suggested that Francis Collins himself was ambivalent towards the NCS, preferring to invest in other projects, such the new NIH Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI). “Collins was far more interested in funding a 500,000- to one million-person cohort study of adult complex diseases,” Scheidt said. In a follow up email, he added that there was a long-standing competition with the National Human Genome Research Institute, which Collins had previously directed. When Collins became NIH director, Scheidt suggested, it had the effect of undermining the NCS.

Scheidt speculated that the NCS was too political, and also too politically vulnerable, and he agreed that Hirschfeld had disregarded his advisors, thereby losing the expertise and support of the scientific community. He also acknowledged that “Collins may have been right — my own leadership and management may have been poor.” But he still wondered whether Collins had personally engineered the study’s demise.

In an email message, Collins rejected this idea. “I have always been supportive of the goals of the NCS and continue to support this area of research,” he said, arguing that by 2014, it had become clear to him — and to the working group he’d empaneled to review the NCS program — that the study was not meeting its goals. “There was no denying that continuing to tinker with the NCS, as had been done over the several years in its pilot phase, was not going to solve the problem,” Collins said.

Kathy Hudson, the deputy director for science, outreach and policy at the NIH, who works closely with Collins on the Precision Medicine Initiative, blamed the NCS’s failure on its governance and leadership structures — and also, she said, “the misprojections of cost, which sent a huge shockwave.”

Some experts feel that the NCS was doomed from the start by aiming to be nationally representative. “That was the fundamental problem,” Goldman said. “It was never going to be feasible to recruit a perfectly representative sample of women in early pregnancy, let alone before they were pregnant, and there were a lot of extremely knowledgeable people at the table pointing that out from day one.”

Even if it had been possible, Goldman added, many of the women and their children would have eventually been lost to the study “so that after a few years, the cohort we wound up with would be very different than the one we started with.”

Whatever the reasons for the study’s ultimate collapse, an enduring question is why so little political blowback had reached the National Institutes of Health. Republicans in Congress, for example, made a sport of pummeling the Obama administration for the failure of Solyndra, the solar tech company that received $535 million in federal loan guarantees, only to go belly-up in 2011. Department of Energy officials were called repeatedly to Capitol Hill to answer for the failure, and a formal investigation was launched. The $1.3 billion spent on the NCS, however, drew no such response from either side of the aisle.

Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard, a California Democrat and one of the most vocal critics of NIH’s decision kill the NCS, suggested in an emailed statement that the turmoil surrounding the study was well known on Capitol Hill and that its problems had a long pedigree, stretching back across two administrations. But at a House Appropriations hearing in March, she said that members of Congress always assumed the NIH would keep pushing forward on the NCS, and that Collins’ decision to pull the plug in 2014 came as a surprise.

“Members of Congress were not notified that the study was being terminated until after that decision had been made and letters had been sent to study participants,” Roybal-Allard said in the email.

Reflecting on whether Congress had held the NIH sufficiently accountable for the wasted public investment, one source with deep knowledge of NCS deliberations, who asked not to be identified in order to preserve relationships in Washington, suggested that it was simply in no one’s interests to advertise a huge embarrassment, and that the NIH enjoys a golden status with lots of bipartisan support. “That’s why you didn’t see more oversight hearings,” the source added. “The NIH never really got a black eye, and most people have no idea how much money was spent on this.”

Collins suggested that all was not lost. “It was disappointing,” he said when asked if the failure of the NCS amounted to a national embarrassment, “but the NCS continues to serve as a source of information on the functionality, feasibility, and outcomes of particular processes.”

Last year, after nudging from Congress, NIH announced plans to begin a successor program, dubbed the Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes, or ECHO program. The new goal is to focus on four key areas of child health: airway diseases like asthma; neurodevelopmental issues, including autism; obesity, and general developmental issues during and after birth. “ECHO plans to combine existing data from multiple, different cohorts to create a large, integrated data set, and to collect new data through standard measures to address the original goals of the NCS,” Collins said, adding that he was “far more optimistic that ECHO will get to many of the answers that the NCS had set out to pursue.”

Whether ECHO will prove successful where NCS fell short will take time to know, but Roybal-Allard suggests that Congress is watching closely. “It is still too early to pass judgment on the direction of ECHO,” she said, adding that she and other members of Congress “have some concerns that the new study protocols might not include sufficient data about pregnancy exposures.”

She also suggested that legislators were angling to increase oversight and accountability of the ECHO program, which, notably, will not be seeking to recruit a 100,000-strong, nationally representative cohort — something that, in the 16 years since NCS was first conceived, other countries, including Denmark, Norway, Japan, and the United Kingdom, have managed to develop with some success.

In February, the NIH also announced that a repository of questionnaire data and biological and environmental materials collected by the Vanguard Centers before they were shut down would be available for use by interested investigators. Most of the biospecimens — everything from placenta, blood, vaginal swabs and urine, to saliva, hair, nails, and breast milk — now lie frozen at a pair of facilities managed by Fisher BioServices, which is headquartered in Rockville, MD.

“The study enrolled over 14,000 participants in over 5,000 families in 40 locations throughout the United States and followed them through 2014,” the agency touted in a notice released to the research community. “It collected more than 14 million records and nearly 19,000 biological and 5,500 environmental primary samples from which a sample repository of over 250,000 items was created. ”

The archive, the agency added, would be made available for “approved research projects by qualified investigators.”

Charles Schmidt is a recipient of the National Association of Science Writers’ Science in Society Journalism Award. His work has appeared in Science, Nature Biotechnology, Scientific American, Discover Magazine, and the Washington Post, among other publications.