Humans Beat Computers in Quantum Research

As artificial intelligence trounces humans in board games like chess and Go, people are questioning whether we really are smarter than machines. But in some recent quantum research involving online games, human players used intuition to solve a complex problem and left computers behind in a pool of silicon dust.

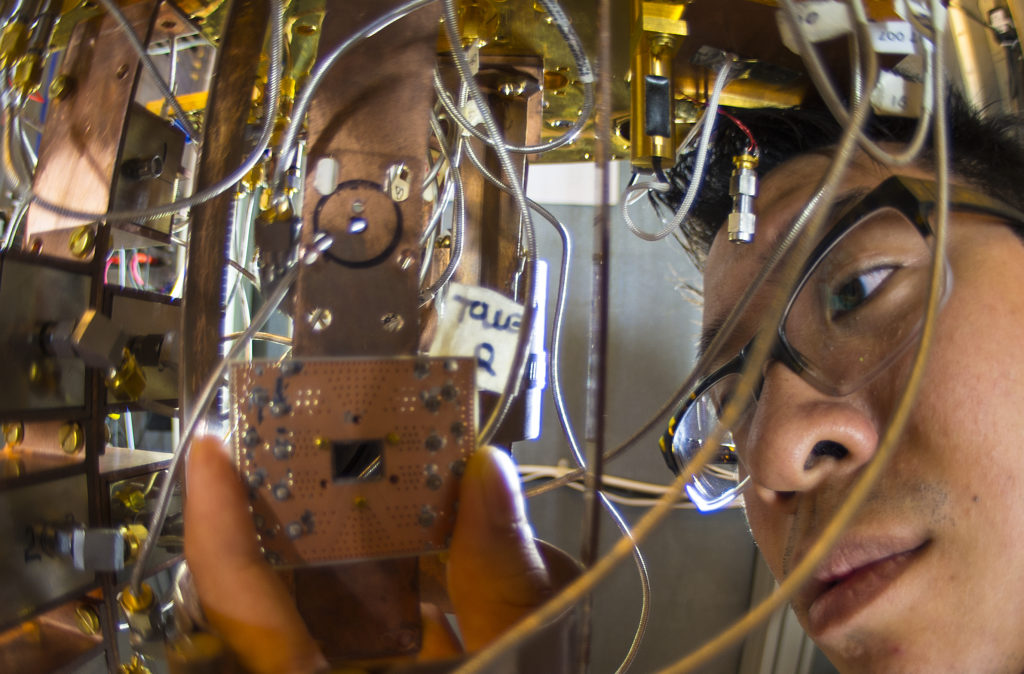

IBM Research scientist Jerry Chow conducts a quantum computing experiment at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, N.Y. IBM has been focusing on quantum computing research for more than 30 years.

As explained in a paper in the journal Nature, researchers from Aarhus University in Denmark looked at a basic quantum computing problem. In normal computing, bits — short for binary digits — can take on only one of two values, 0 or 1. In quantum computing, individual atoms called qubits, or quantum bits, sit in two quantum states at the same time and simultaneously represent both values. A highly-focused laser called an optical tweezer is used to move the qubits around to perform computation. Qubits are naturally unstable and are affected by their environment, so the faster you can move the atoms from one place to another, the more efficient the quantum computer will be.

But a theoretical limit called the quantum speed limit caps how quickly you can move those atoms before the information is gone.

Figuring out the optimum path of movement is fiendishly difficult for a computer. According to Jacob Sherson, an associate professor at Aarhus University and one of the paper’s authors, finding the answer is the equivalent of solving a 1,000-dimensional problem. Researchers have looked for optimized solutions until the information is lost and the process fails. At that point, they have assumed that they have run into the quantum speed limit.

Moving a qubit is similar to the way you move a glass filled to the brim with water. If you move too quickly, you risk spilling the water over the side of the glass and have to adjust to keep it steady. With this in mind, the researchers turned to citizen science for help through an online game. Volunteers moved a simulated container of liquid on the screen, trading off speed and the need to keep the liquid contained. Most attempts were worse than computer solutions, but a handful of players bested all machine attempts. Those players found ways to move fast and yet adjust the container just right so the faster speed didn’t create a data loss.

“Players have found solutions that we would have thought physically impossible,” said Sherson, meaning that previous estimates of the quantum speed limit are wrong.

Even though the liquid exhibited both classical and quantum characteristics, humans used intuition to simplify the complex problem, much as someone catches a ball thrown through the air without considering drag, wind speed, temperature and other factors.

One exciting implication of these results is that researchers can study the patterns of how people approached the problem and adjust the computerized optimizations accordingly. Another is that matching people against computers in rules-based games like Go or chess may be limited in what it can show about intelligence.

“I think we’re underestimating human abilities by making this the ultimate test of humans,” Sherson said. “The ultimate test is to be able to perform in uncharted territory and rules of interaction and to be able to adapt to all these situations.”

And that may be exactly what humans are best at.

Correction: This post has been updated to correctly define the quantum speed limit and to include how moving atoms too slowly or too quickly can affect qubit information retention.