Toward a More Peaceful (and High-Tech) Coexistence with Sharks

Australia may be one of the few countries where scientific reports about great white sharks can regularly trigger fierce political debates. The country has the world’s highest fatality rate from unprovoked shark attacks with an average of 1.5 deaths per year. That’s a very low risk, but still a concern for water-loving Australians who primarily live near the coasts — and that concern has traditionally been addressed with a suite of what many critics have called overly aggressive solutions like shark nets or baited drum lines that have one summary purpose: killing sharks.

That has some officials and conservation advocates embracing newer shark surveillance systems that promise to use artificial intelligence techniques to automatically identify sharks in the water. The technology is in its early days, and many hurdles remain. But supporters of AI-assisted shark surveillance hope such systems might offer a middle ground for Australian political factions that frequently fight over lethal versus non-lethal approaches to dealing with shark attacks. And as technology startups look to peddle their innovations to hotspots for human-shark encounters not just in Australia, but from California to Cape Town, conservationists are hopeful that they might one day encourage a more peaceful coexistence between sharks and humans in general.

“It is quite obvious that beachgoers and beach recreation will become safer with the shark mitigation technologies, but it is also important for us not to disturb the marine life in general,” said Nabin Sharma, a lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney. “This is a win-win situation for both sharks and humans.”

One example of Australia’s heightened shark surveillance involves drones that conduct hourly patrols over 40 beaches in New South Wales and eight beaches in Queensland on the country’s east coast. The devices have a maximum flight time of 28 minutes and spend the rest of each hour on standby. In addition to identifying swimming hazards like rip currents, a dozen of these drones carry an AI algorithm called SharkSpotter, which can tell the difference between objects such as swimmers, surfers, boats, rays, dolphins, and sharks.

Developed by startup The Ripper Group and underwritten by Australia’s Westpac Bank, the drone’s algorithm was trained to recognize different objects based on examples culled from drone camera footage taken over Australia beaches. “It is not expected that an AI system will work straight away after deployment, as there are many unknown scenarios,” said Sharma, who worked with Michael Blumenstein and other AI researchers at the University of Technology Sydney. “It will become better and more accurate based on further fine-tuning.”

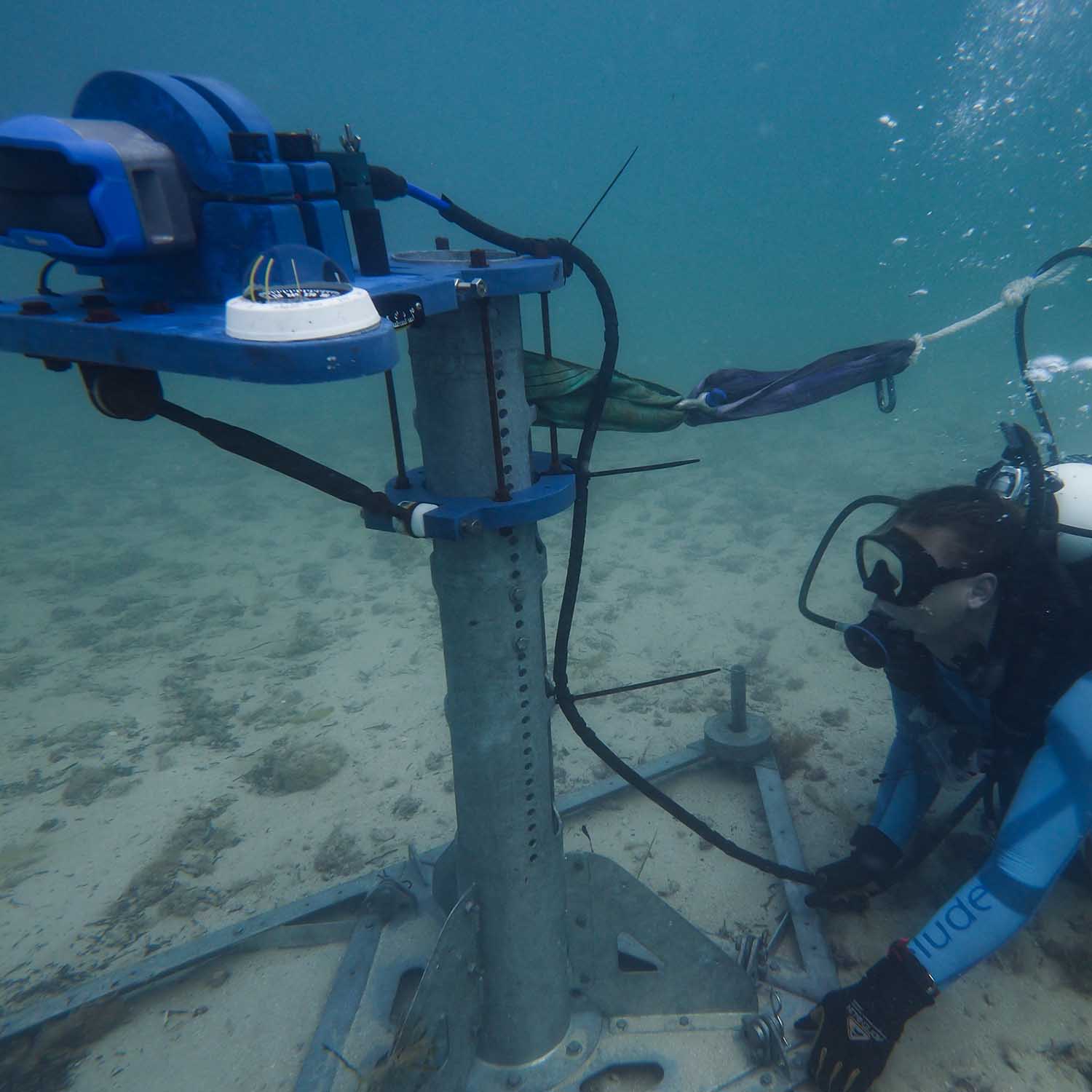

Another shark surveillance system, called Clever Buoy and developed by Perth-based Smart Marine Systems (SMS), relies upon underwater sonar arrays to send out acoustic pulses and return an echo of nearby objects. The active sonar can track any sizeable marine animal within a certain radius, unlike passive acoustic systems that many shark researchers use to track specific sharks tagged with transmitters. “What we’re developing is a pattern-recognition algorithm for the ocean,” said Craig Anderson, co-founder and executive director of SMS. Each animal in the ocean, down to the sub-species level, Anderson said, “has its own unique fingerprint, and that fingerprint is the way it swims.”

If the system’s pattern recognition software identifies the object’s unique swimming motion as belonging to a large shark — as opposed to a dolphin or stingray — the Clever Buoy texts an alert to lifeguards. The text prompts them to open a mobile app that reveals more information about the shark’s size and allows them to track the shark’s location with updated GPS coordinates.

In 2015, Australia’s New South Wales government announced a five-year commitment to install Clever Buoy at beaches on the east coast. The system has been deployed at Bondi Beach, one of Australia’s most iconic beaches near Sydney, along with City Beach, the main beach for the city of Perth on the west coast. The system has also provided temporary protection during World Surf League championship rounds held in Australia and South Africa.

Of course, there are limitations to these approaches. Neither SharkSpotter nor Clever Buoy can yet tell the difference between specific shark species — a factor that can make a huge difference in terms of the potential threat to humans. “The next part of our journey of learning is distinguishing species of shark,” Anderson said. “We don’t want to be closing beaches and pulling people out of the water if it’s a nice friendly gummy shark.”

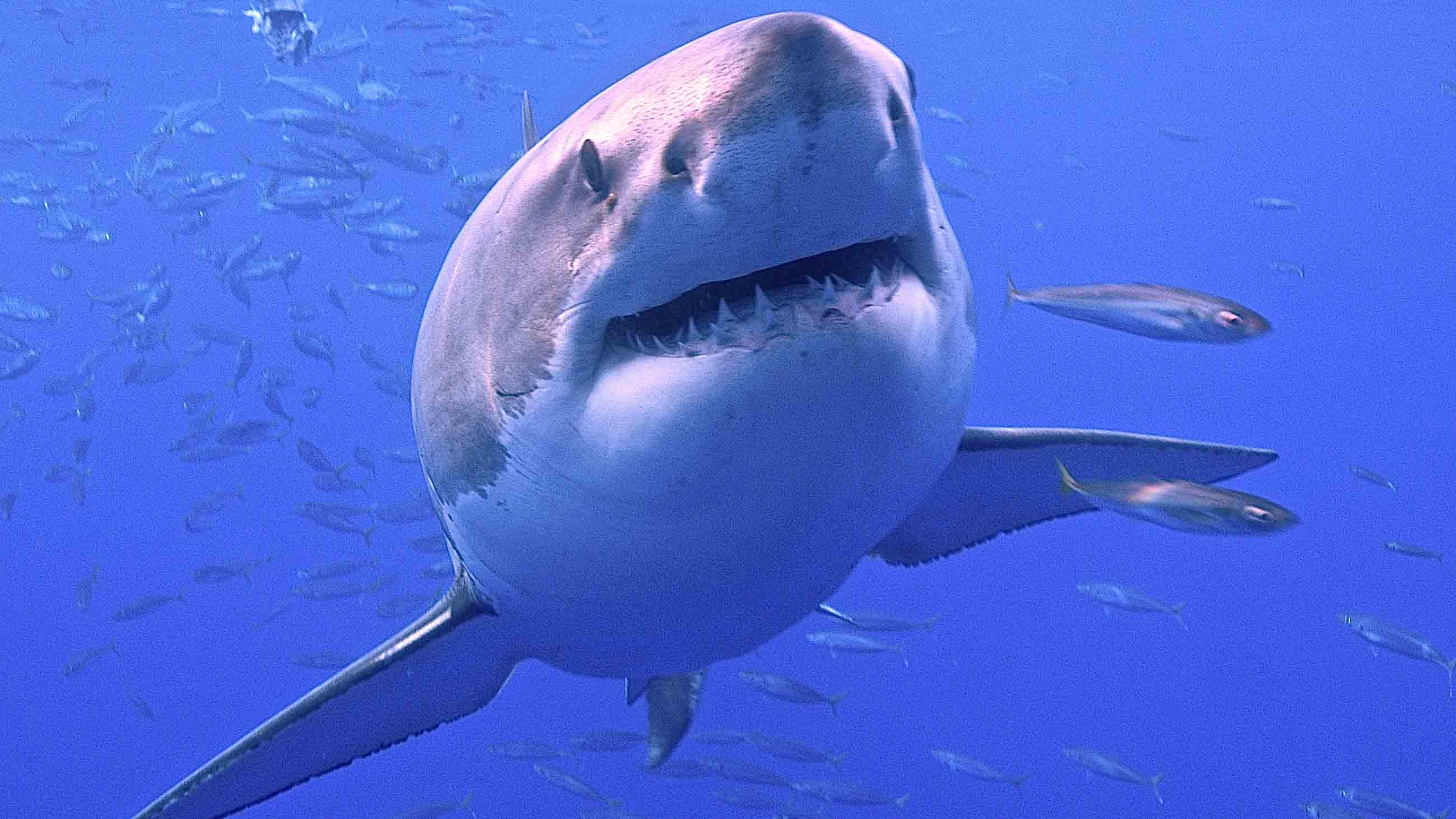

Those distinctions matter. Of more than 500 known shark species, just 26 have been positively flagged in unprovoked attacks on humans. But Australia has 22 of those 26 shark species and most of the shark species implicated in fatal, unprovoked attacks. Australian waters also have the three shark species that account for the majority of fatal shark attacks: tiger sharks, bull sharks, and great white sharks.

Yet the frenzied political and media responses to shark attacks can seem disproportionate to the low odds of ending up a shark attack victim. In 2017, unprovoked shark attacks amounted to just 88 confirmed cases worldwide, including five fatal incidents, according to The International Shark Attack File at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville. By comparison, about 3,500 Americans die from accidental drowning every year. At the same time, humans kill about 100 million sharks each year. Even the great white shark, made infamous by Hollywood films such as “Jaws,” has gone from being a top predator of the ocean to a vulnerable target of trophy-seeking fishing boats.

Too many unknowns exist about shark behavior and population to explain why the overall number of shark attacks has crept upward in recent years. For example, there is no evidence to suggest that the possible recovery of certain legally protected shark populations is linked to a greater risk of shark attacks. Instead, shark experts say that a bigger factor comes from more swimmers and surfers entering the water.

“In California there is evidence of a substantial degree in bite-on-humans largely due to the massive increase in water users over the last 20 to 25 years,” said Christopher Lowe, a marine biologist and director of the Shark Lab at California State University, Long Beach. “Per capita bites have actually gone down, even with potential rise in shark populations.”

But the impact of shark attacks is not limited to the rare tragedy of limb or life lost. Even lone shark attacks can scare away beachgoers and hurt businesses dependent on crowds of locals and tourists. A cluster of shark attacks within a short timespan can damage a community’s sense of security as entire families may witness attacks taking place just offshore.

“If you speak to anyone in shark-bite areas in the world, they will say that when one or two shark bites happen, it’s incredibly sad and tragic,” said Sarah Waries, project leader for the Shark Spotters program in Cape Town, South Africa. “But you don’t get the incredibly visceral emotional reaction you have when a spate of shark bites tips a community over edge to the point where people don’t feel safe anymore.”

Cape Town took action after suffering a spate of shark attacks in 2004. The local business and surfer community began informally organizing lifeguards and car guards to help keep watch with binoculars from a mountain overlooking the beaches near False Bay. If a spotter sees a shark approaching the beach, the mountain spotter radios a beach spotter who manually activates a simple warning system consisting of different-colored flags and a siren that alerts people to leave the water.

Funding from the City of Cape Town and the Save Our Seas Foundation helped the effort evolve into the formal Shark Spotters program (no relation to the Australian drone initiative). For 14 years, the program has shown how a low-tech community approach can help reduce the risk of shark attacks.

Like Australia, South Africa’s Shark Spotters program has experimented with using drones. But the drones’ limited battery life of 15 to 20 minutes and high wind conditions made them fairly ineffective in providing constant shark surveillance, Waries explained. They proved more useful in confirming the identity of specific shark species after human spotters made the initial discovery.

A more promising effort could complement human spotters with automatic shark spotting based on fixed cameras installed high up on poles or towers. Shark Spotters has teamed up with PatternLab, a company based in Lausanne, Switzerland, to develop the necessary pattern-recognition software. But the South African programs generally make do with more limited resources in comparison with Australia.

For their part, U.S. shark researchers seem to take a more cautionary view of the latest “smart” shark surveillance technologies — particularly given their inability to distinguish between different shark species. “A [great] white shark is a very different organism than a blacktip we see in Volusia county,” said Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “They’re as different as a human is from a dog.”

Environments also play a factor in a technology’s effectiveness, said Gregory Skomal, a marine biologist at the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. He cited the cost and lack of funding for testing such equipment in local waters. “All these technologies will depend heavily on the area you’re trying to deploy them,” Skomal said. “Something developed for clear water in Australia may not work well in the turbid waters of Cape Cod.”

Still, if such technologies can help Australia strike a better balance between protecting humans and protecting threatened marine species, it could mean a lot less blood in the water — and increased buy-in for such innovations elsewhere. As it stands, the high price tags have not dampened the enthusiasm of Australian startups for market expansion. The Ripper Group has been talking with seven different international organizations about expanding its drone surveillance worldwide, said the company’s chief operations officer Ben Trollope.

Craig Anderson and Smart Marine Systems have also launched a $25,000 crowd-funding campaign aimed at deploying Clever Buoy at Corona Del Mar in Newport Beach, California, the site of a non-fatal 2016 shark attack on a triathlete.

“I think we’ll very quickly follow through with Florida and Massachusetts,” Anderson said. “This is just the start of what we see as a significant rollout.”

Jeremy Hsu is a freelance journalist based in New York City. He frequently writes about science and technology for Backchannel, IEEE Spectrum, Popular Science, and Scientific American, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I think it’s a great idea protects both sharks and humans without bringing harm to either of them

Shhh don’t mention the “protection” order from 1992′