In Reproduced Miniatures, Afghans Regain a Lost Cultural Heritage

Despite it being a particularly warm afternoon, the halls of the Queen’s Palace in the Babur Gardens of Kabul were filled with light chatter. The bright May sunshine did not seem to have deterred the students, visiting from a local university, who moved slowly through its long corridors, carefully inspecting one display after another, engaging in muted conversations.

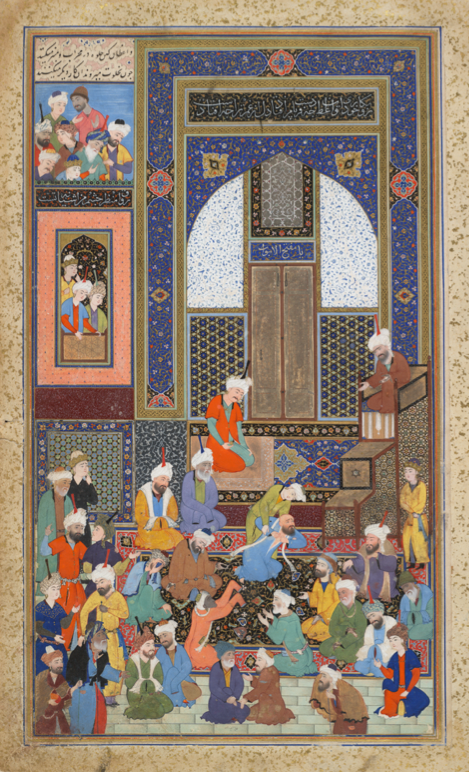

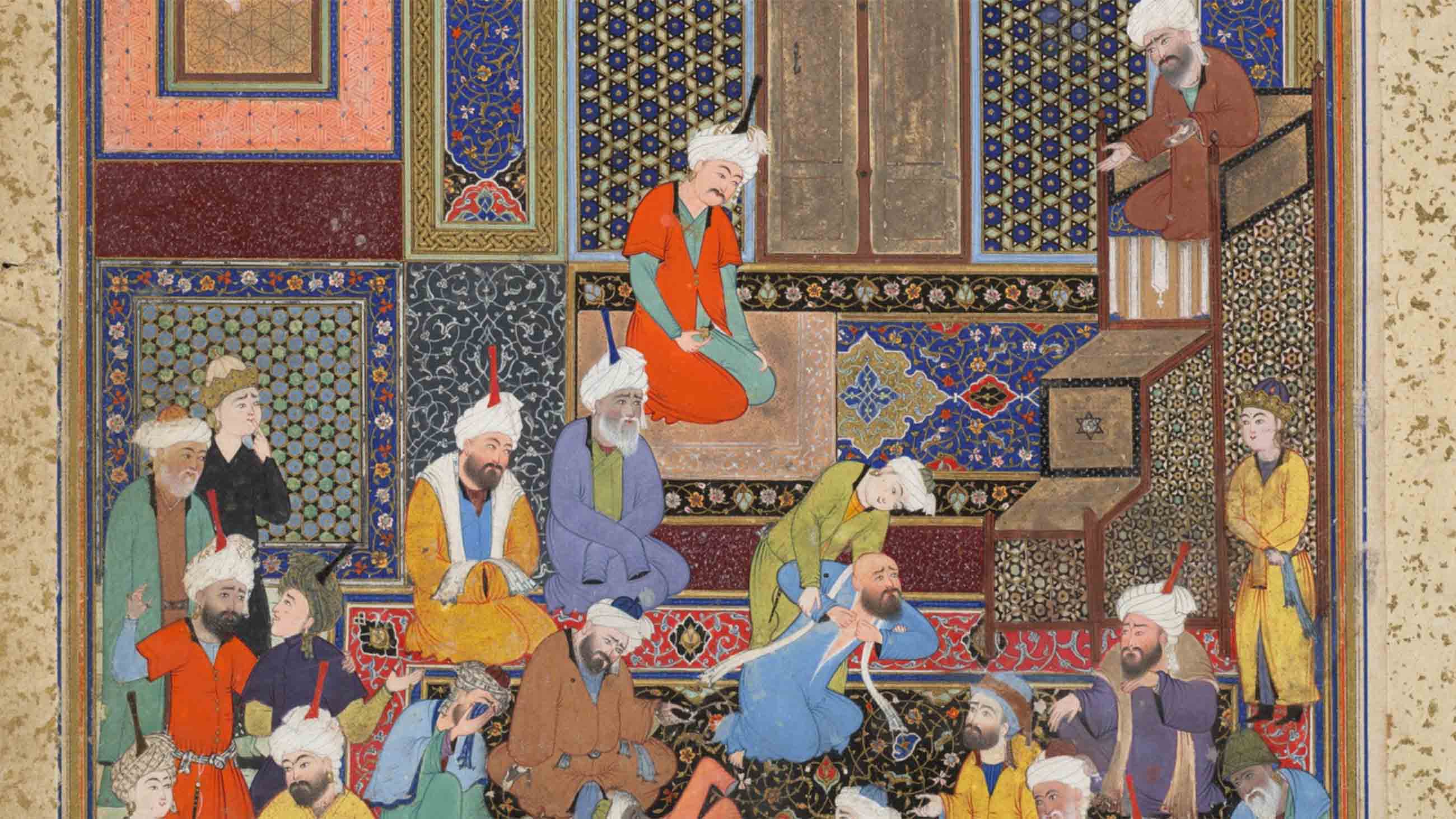

The original images are held in collections the world over. Here, a plate called “Incident in a Mosque” — also detailed in the top image — comes by way of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum at Harvard.

Visual: Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Stuart Cary Welch, Jr.

They had come to observe a series of Mughal-era paintings that were exhibited in the 500-year-old complex that also serves as the resting place of Babur, the emperor who ruled over large swathes of the Indian subcontinent in the early 16th century. An initiative of the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies (AIAS), this exhibition, and another in the city of Herat, features a collection of exquisitely enlarged reproductions of rare miniature Afghan paintings from the 15th to 18th centuries. The works had been gathered and curated from museums and libraries around the world to be exhibited in Afghanistan — their place of origin — for the first time since they were created.

A small cluster of students was huddled close to one particular painting that seemed to attract a lot of interest and debate. “It shows how Afghan women were educated and a part of literary history, even 500 years ago,” one young woman pointed out, drawing comparisons to the state of women’s conditions in Afghanistan in the last three decades, particularly during the Taliban regime, which banned women’s education.

“The ravages of Afghanistan’s culture and national identity has been so terrible that one of the first things that anyone concerned with the revival of this country has to take into account is restoring awareness of its most glorious artistic heritage,” explained Michael Barry, a professor of history at the American University of Afghanistan and the curator of the exhibits. “Affirming defense of cultural heritage is absolutely inherent to protecting human rights.”

That these paintings were on display in Afghanistan at all is a testament to both modern technology and international cooperation. The 69 images in the Kabul exhibition came from 17 international art collections, while the 106 images on permanent display in Herat came from 20 collections. No single original painting from the period covered remains on Afghan soil, according to the exhibit organizers — a fact that may well have protected the hand-painted imagery from the ravages of war, but also robbed the Afghan people of their cultural legacy.

But in collaboration with Central Dupon Images, a Paris-based firm specializing in art publishing, the team at AIAS were able to enlarge and reproduce the miniature paintings — often smaller than 10 inches across in their original form and culled from medieval manuscripts — onto large-form metal sheets to bring them for display in a conflict zone. “These images had to be extremely high, heavy, and quality files. Each image was 300 DPI or higher and weighed over 80 megabytes,” explained Jean-François Camp, the CEO of Central Dupon in Paris. Most museums already had high-definition scans available, but AIAS had to commission several new scans.

“The originals were smaller than [standard paper] size in some cases and to reproduce them into much larger prints while improving the quality was a challenge,” said Camp. “We first made small sets of the color- and definition-corrected versions, and after they were approved, we enlarged the results for printing.”

The results were enthralling; Mikaela Ringquist, grant director at AIAS, recalls seeing the improved reproductions and comparing them to the originals. “Some of the paints that they used to make the originals were derived from crushed precious metals and stones including silver and gold,” she noted. “For example, a river would be colored with silver, but over the years the metal gets oxidized and the river looks blackish in the originals. But when you see them in reproductions, those colors have been corrected and enhanced to look more like how they were intended to be.”

The larger versions of the paintings also serve the purpose of providing a detailed and immersive experience to the Afghan viewers who might otherwise not have the opportunity to examine these paintings up close. “By blowing up these images, what we get to see is the extraordinary minute details such as facial features which these 15th- and 16th-century artists were able to accomplish before the age of magnifying glasses,” Barry noted. “They used bottles of water which they held over the painting and we can see this extraordinary fine brush strokes or stylus works made in this manner.”

The choice of Dibond aluminum canvases was also deliberate. Lightweight, durable, and flame retardant, the canvases — which consist of two sheets of razor-thin aluminum sandwiching a polyurethane core — can withstand sunlight, wind, water, and other outdoor exposures. And of course, as enlarged facsimiles of the originals, they constitute a low risk amid Afghanistan’s ongoing security woes. Each reproduction cost a mere $350. The originals, on the other hand, are priceless.

Not surprisingly, these realities rankle some Afghans, who believe the original images should return to their place of origin — but experts say the security situation, as well as knotty questions of ownership, make that unlikely to happen anytime soon. “If the insurgents or a suicide bomber were to walk in to Babur Gardens and destroy these paintings, it wouldn’t amount to the damage of the [original] art,” noted Ringquist, who called the exhibit of reproductions “the next best thing to actually bringing in the originals.”

“The paintings can be easily reproduced in a relatively economical budget,” she said.

Barry goes further, arguing that the metallic reproductions are in fact better than the real thing. “The originals, where they are housed — even there [they] are very rarely seen,” he said. “They fear the light of day, they are kept in the dark, and are only exposed in rotation for brief periods.

“By reproducing these images on metal with terrific definition, we are now in a position to exhibit them to large crowds without any danger to the originals,” Barry added. “We can give a privileged view of these masterpieces, thanks to the state-of-the-art technology, in a way they have never been seen since their royal owners were able to look at them 500 years ago.”

The exhibition in Herat has been made permanent by the local government, which has provided the paintings a home in the 2000-year-old Herat Citadel. The Kabul reproductions will eventually be moved to the American University of Afghanistan, where Barry says he is working on plans to expand this project further — and to bring similar glimpses of Afghanistan’s history back to its people.

“It establishes for Afghans that their ancestors created something great which stood on a high rank with the greatest works of art in the world,” Barry said. “The fundamental message is, if you can create such wonderful art, you are capable of anything.”

Ruchi Kumar is an Indian journalist currently working in Kabul, Afghanistan, focusing on news stories from the Afghanistan-Pakistan region. She has been published in Foreign Policy, The Guardian, NPR, The National, Al Jazeera, and The Washington Post, among other outlets.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

How do I purchase a print of the art?

I agree with you