The fates of humans and coastal ecosystems are often more intertwined than we realize. Nearly 40 percent of Americans, or about 120 million people, live on the coasts — along with thousands of breeding pairs of ospreys; millions of shrimp, lobsters, salmon; and countless other species of birds and bugs, mammals and plants. And as the climate changes, the seas rise, and more intense storms strike our coasts, the wild inhabitants share vulnerabilities and risks with their human residents.

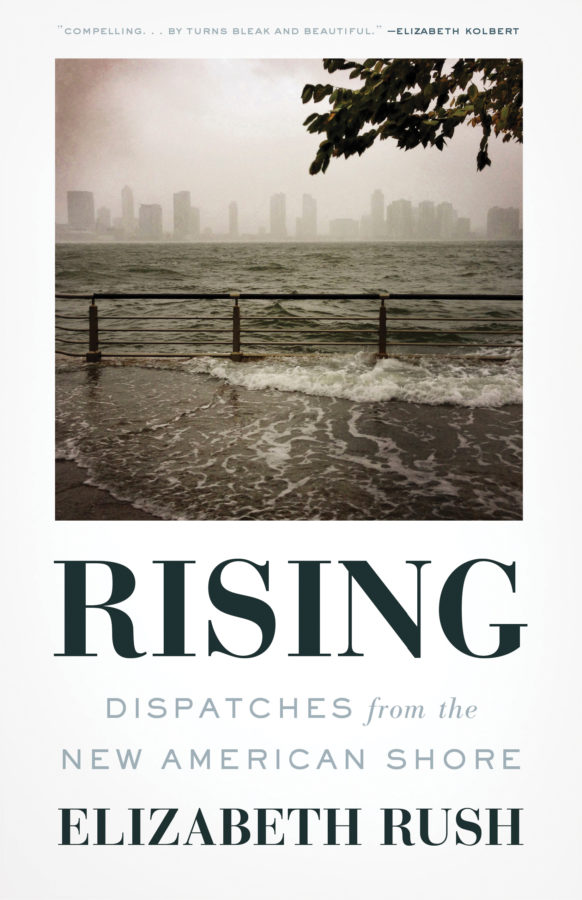

BOOK REVIEW — “Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore” by Elizabeth Rush (Milkweed Editions, 320 pages).

This fall, as Florence and Michael raged across the Carolinas and Florida, the storms tore apart homes and communities — and also nesting sites for birds and sea turtles. In 2017, 23 million Americans were besieged by hurricanes on the Atlantic Coast, the Gulf of Mexico, and Puerto Rico, and hundreds of thousands were displaced. Wildlife also lost their homes, sometimes with devastating implications, and rare coastal ecosystems, including one of the nation’s only tropical forests, took a heavy beating.

Even the less dramatic but more frequent flooding caused by sea level rise is a risk to human and animal communities alike. Saltmarsh sparrows, for example, are having troubling keeping their hatchlings alive as tides get higher; meanwhile, worries about toxic black mold are on the rise in flood-prone communities along the coasts.

Elizabeth Rush’s new book, “Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore,’’ is a timely meditation on climate change, the American coasts, and the losses all of us — human and non-human — face as the seas rise. Rush, a visiting lecturer at Brown University, has one foot in the world of academic creative writing and the other in science journalism. Her book is partly a work of reportage. It is also an effort to create a story form — through a collage of images and narrative structures — that is expansive and fluid enough to reckon with the immensity of climate change and its impact on such minutiae as the timing of bird migrations and the survival of tupelo trees and seagrass meadows.

The book is not exactly nature writing — a style of literary expression that often romanticizes untrammeled nature and sometimes feels like a quaint relic of an age when the impacts of climate change weren’t so obvious. Nor is it quite disaster narrative, since climate change only occasionally manifests itself as all-out catastrophe and more often as the slow accretion of damage and the erosion of the things we value.

But Rush borrows from both genres. Brief monologues like those used by the Russian writer Svetlana Alexievich in her account of the intimate human dimensions of nuclear catastrophe, “Voices from Chernobyl,” alternate with lyrical passages that often seek transcendence through attention to small gestures and wingbeats, in the manner of Annie Dillard.

Rush also shares some of the British author Robert Macfarlane’s fascination with neglected words, which act as anchor points in a narrative that could otherwise feel labyrinthine. Two relatively obscure botanical words, in particular, serve as key metaphors. The first is rampike, which describes a broken or dead tree. The demise of coastal wetland trees like tupelos and mangroves is an early sign of sea level rise, and the skeletons of dead trees appear in scene after scene. The rampike is Rush’s metaphor for loss, and she uses it to string together elegiac accounts of places and communities being drowned or washed away.

She travels to Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, the eroding island community whose plight became the basis of the movie “Beasts of the Southern Wild.” She knocks on doors in impoverished flood-prone neighborhoods in Miami and Pensacola, where residents are already beginning to evacuate as the water defaces and devours their property. She follows scientists into swamps and salt marshes in Florida and Maine, and witnesses how the plants that hold these places together are dying and rotting.

All of these are battlefronts in the same global-scale confrontation: as the water moves in, the animals, plants, and people must either retreat or try to stand their ground — the latter often at great cost and with dubious prospects of success.

Rush’s second organizing metaphor is a rhizome, a rootlike bit of plant anatomy. In some wetlands, Rush notes, rhizomes can help plants cope with climate change by sprouting new shoots underground and sending them uphill so the plants can, in a sense, retreat from the rising water.

For Rush, the lesson of the rhizome is to retreat artfully in order to survive. For the most part, wherever she finds loss, she also finds examples of resilience and renewal. One of the best is Oakwood Beach on Staten Island, New York, a community that voluntarily and almost unanimously decided to use post-Hurricane Sandy recovery money to disband, give up their properties, and move away from the water’s edge. Where Oakwood’s houses once stood, the land is reverting to a coastal wetland that will help buffer other parts of New York against flooding. Rush sees their en masse relocation as an act of strength: “The retreating residents of Oakwood, by banding together and demanding aid,” she writes, “are less victims than agents. More rhizomes than rampikes.”

Rush is more interested in so-called soft strategies for managing sea level rise — those that rely more on natural ecosystems to handle floods — than on, for instance, giant manmade flood barriers. She focuses her final chapter on the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project, in the San Francisco Bay Area — one of the nation’s largest efforts to put a wetland back together. Here, scientists are trying to engineer a new coastal landscape so that plants and animals can adapt and flee when the sea rises.

The book takes a few unexpected detours, including a wrenching discussion of Rush’s experiences with sexual harassment while reporting some of her stories. It’s sadly not surprising to hear about a female reporter getting harassed in the field, but rarely are these experiences disclosed in a science book. Rush’s revelations don’t feel out of place — she weaves them into a broader discussion about risk and vulnerability, class, gender, and race, and the challenges of addressing climate change in a fundamentally inequitable society.

Though “Rising” is generally not a polemic, toward the end Rush offers a passionate plea for better funding to help those living in America’s expanding flood zones. “Too many times I have been told that there will never be enough money in the federal coffers to relocate everyone away from the risk of rising tides,” she writes. “This is true until we decide to make it untrue.”

There’s little about the role of fossil fuels or about strategies to mitigate climate change by reducing carbon emissions. Rush chooses instead to ground her story in the tangible details of particular places and communities.

This means the book misses some opportunities to call people to action. She offers few reflections on a fundamental truth about sea level rise: that continued delay, ineptitude, and inertia will drown ever more communities and wetlands.

But in focusing on the immediacy of loss and survival along the American coast, she opens the door to other kinds of discussions and perhaps to audiences who would otherwise avoid the big, politically charged subject of global warming. Instead, she invites readers to consider where we are now and who we might become as the rising tides dismantle and remake our seaward edges.

Madeline Ostrander is a freelance science journalist based in Seattle. She has written on climate change for Undark, and her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Audubon, and The Nation, among other publications.