In California, Helping the Homeless to Make Their Medical Preferences Clear

Chris, a 40-something homeless man who spends much of his time within sight of the Pacific Ocean, has thought about his death. During his years on the street, he’s suffered from a range of chronic ailments, including a neurological disorder that limits his speech and coordination. He’s resigned for the time when something more serious comes along.

“It depends on if it’s something like a broken foot or an easy problem, but not if it’s fatal,” he says. “It’s just waiting to die. Why fight the inevitable?”

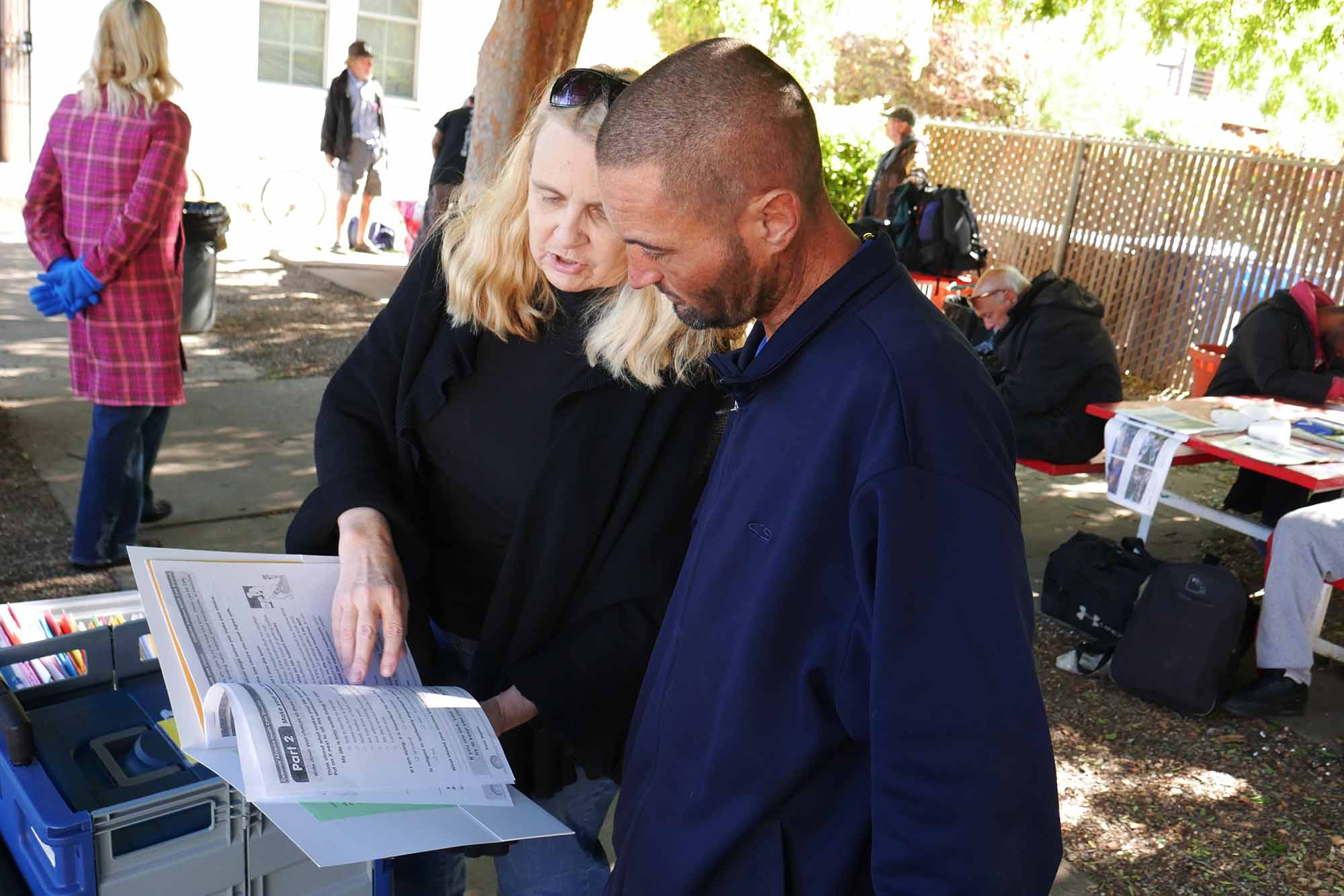

The St. Robert’s Center, a few blocks from the beach in Venice, California, is a strange place to ask people how they want to die. Yet, at least one Saturday morning a month, two nurses appear to do just that, nudging several of the three dozen homeless people in attendance to make some concrete end-of-life plans as they socialize over sandwiches, bananas, and coffee. The nurses engage attendees in chitchat with the goal of guiding them to fill out advance care directives (ACDs), much more comprehensive than the standard “do not resuscitate” orders.

Most who complete the ACDs carry them in their backpacks. Some have cards referring doctors to the hospital where their ACD is on file. One man who gave his name only as Chris keeps his card in his wallet. “Maybe one day I’ll wear it on a necklace around my neck,” he says.

While this sort of solicitation may sound ghoulish, the outreach team and many of the attendees call it a service. Americans living without shelter often suffer from debilitating conditions they can’t afford to treat, and are typically just one more bad turn from a rendezvous with an emergency medical technician. The nurses say if and when that happens, they should be carrying ACDs that lay out how they want to be treated, whom to contact, and, less optimistically, considerations like whether they want to donate their organs.

Chris was a “no” on organ donation: “Nothing in my body works good.” Nurses say the directives were created specifically for this population, forgoing legalese and intimidating medical terminology of typical ACDs.

Funded by a $10,000 grant from the non-profit Coalition for Compassionate Care of California, the advance care planning team of nurses and doctors have distributed more than 260 folders containing ACD paperwork to people like Chris since they began visiting St. Robert’s in 2015. But much work lies ahead. In the last three years, the homeless population in Los Angeles County alone has grown 23 percent to almost 60,000 in 2017.

“In the absence of documentation or a designated decision maker, the default is aggressive therapy,” says Jeannette Meyer, who specializes in palliative care at the UCLA Medical Center of Santa Monica and heads the St. Robert’s outreach team. “We started this project because homeless patients were receiving painful and sometimes futile therapies leading to a quality of life they wouldn’t want.” With that in mind, the team has also gently started the end-of-life conversation with many more people.

The outreach process starts casually, says Theresa Haley, a care planning team member and a clinical instructor at UCLA’s medical school. “After about six conversations, they might feel comfortable filling out a form. The first conversation might be about dental or eye care needs, and once they get to know us, they might open up and talk about something a little more meaningful.” Word of mouth helps, too, she says.

“The homeless are in the middle of a storm, in survival mode on a day-to-day basis,” says Coley King, director of homeless outreach at the Venice Family Clinic. Among the most common conditions he treats are hepatitis C, alcoholism, and cirrhosis, he says — wasting diseases that can’t be effectively treated with the kind of emergency-room care that is the last resort of the destitute in the U.S.

“In the absence of documentation or a designated decision maker, the default is aggressive therapy,” Meyer says. Still, doctors aren’t required to abide by an advance care directive.

Visual: Larry Buhl for Undark

Doctors aren’t required to abide by an ACD, and some won’t honor one that wasn’t already in their particular hospital’s files. Because patients usually choose to keep the ACDs with their primary care physicians, the registries are typically not the to-go place for ER doctors. The California ACD registry started in 2000 and includes fewer than 7,000 names. A robust nationwide registry accessible by all hospitals would be ideal, Meyer says. And it should be free. But for the homeless population, the $10 fee to file on the California registry might as well be $1,000, she says.

Later that morning, Jeannette followed up with another man, also named Chris, whose recent asthma attack landed him in the ER. His health directive said that he would not want his life sustained on a breathing machine. Fortunately, it didn’t come to that, and Chris was discharged the same day. He told Meyer that doctors were able to access his directive easily and would have honored it if his condition were dire.

“I was about to do cartwheels,” Meyer says. “It works.”

Meyer concedes that Chris was lucky because he was sent to one of the five medical facilities that share patient files. If he had been in downtown L.A., for example, a doctor or nurse would have to call the hospital where his ACD resides, and, because the file is not in their system, might not have honored it.

The advance care planning team recognizes that they can only reach a tiny fraction of the area’s total homeless population, but they hope the program will soon expand to cover more of the city.

King, who liked the idea of health directives, says that if and when the outreach program is expanded, it should include teaming up with street outreach efforts. “To have some efficacy and prevent aggressive health intervention in people who don’t want that, you should find people who are already sick with these conditions and give them some counseling and a directive rather than the general homeless population.”

He adds that it’s a sensitive topic and the approach requires finessing. “It can’t be a cold approach. There needs to be a warm hand-off from a team that knows them.”

Larry Buhl is a writer and radio producer based in Los Angeles. He has produced for the BBC, Marketplace, Free Speech Radio News, and Pacifica radio.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of the piece incorrectly identified the source of the ACD grant funding. It was provided by the Coalition for Compassionate Care of California, not the California Health Care Foundation. The number of folders distributed by the ACD team has also been updated.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Your otherwise fine article is inaccurate regarding Advance Healthcare Directives. Healthcare providers must ordinarily comply with a properly executed Advance Healthcare Directive. Exceptions are noted in the 2018 CHA Consent Manual: providers may decline to comply for reasons of conscience; contrary to hospital policy; or instructions that require medically ineffective treatment. see 3.12 of the Consent Manual. Please encourage compliance.