Lydia Kang is a doctor of internal medicine in Omaha, Nebraska, who has had her writing published in an array of leading journals, from Annals of Internal Medicine to The Journal of the American Medical Association. But beyond that, she is a best-selling author of fiction, including murder mysteries and sci-fi, and co-author of an acclaimed new nonfiction book on insanely bad medical practices throughout history.

“If I could fly a banner over my office door, it would be ‘Prevention.’”

Visual: TEDxOmaha/Dog & Pony Productions

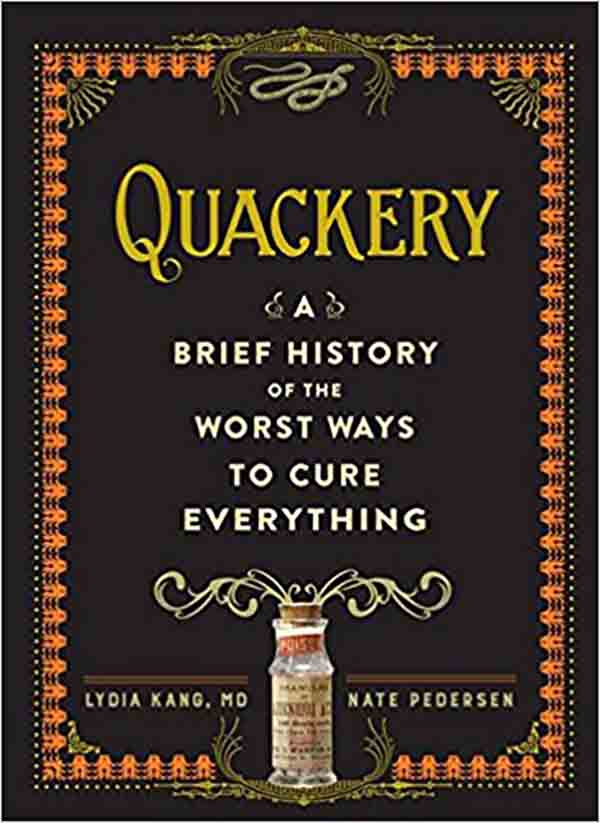

A fascination with medicine and chemical compounds, for good and for not-good-at-all, illuminates her work. The heroine of her novel “A Beautiful Poison,” published last August, has a “passion for scientific discovery” and a fearless determination to solve a murder. Last fall, together with Nate Pedersen, a writer and historian based in Oregon, she published “Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything.”

As in the mystery novel, poisons play a starring role in “Quackery”: The book explores some of medicine’s most bizarre theories on the uses of everything from arsenic to radium. But it ranges widely through the territory of bad medicine, from a somewhat grisly exploration of old surgical instruments (in a chapter titled “Slicing, Dicing, Dousing, and Draining”) to the unsuccessful use of dog and guinea pig testicles as an old-age treatment.

Kang recently discussed the book, and why such evidence-based history matters, in a talk featured on C-Span. In her brief Q&A with Undark, you’ll notice that she twice mentions fact checking: Accuracy in public understanding of medicine is one of her major writing motivations. Early in her writing career, she made a point of letting other writers know she was available to provide a doctor’s insights as to whether they had their facts right. In response, one grateful author wrote a Dr. Kang character into a book.

UNDARK — How much does your medical background influence your choice of material — such as the murders in “A Beautiful Poison,” or the often strange (and dangerous) remedies in “Quackery”?

LYDIA KANG — I enjoy a tinge of the gothic in a lot of my novels, and I’m fascinated by our mortality and how characters see themselves within the confines of a very susceptible human body. So anything that involves poison or the macabre or murder are things that I really find endlessly interesting — the complete opposite of what I do in my medical practice, which is primary care. In my day job, I’m in the business of keeping people healthy. If I could fly a banner over my office door, it would be “Prevention.” Ultimately, I don’t usually choose a storyline based on my background as a physician. It’s really just a very convenient repository of information for me to use when needed!

UD — You’ve written more fiction than nonfiction. Do you prefer one to the other? And how was it working with a co-author on your nonfiction book, “Quackery”?

LK — Writing “Quackery” these last few years was incredibly eye-opening for me. I have a new appreciation for the work of journalists and nonfiction writers now. There was a pattern to how researching each chapter went — research until I had a body of information to comfortably work with; write; revise and research some more; revise again — and keep fact checking. Very steady and soothing in a way, yet confining.

Fiction has its own set of rules, but since I’m the creator of those universes, the freedom is rather intoxicating. As for writing with a co-author, Nate and I ended up splitting the chapter topics down the middle. (It was like a blowout Black Friday sale with only two shoppers and the weirdest store you ever saw — “I want Opium!” “I want Magnetism!” “I want Cannibalism!”) After every few chapters, we’d exchange and fact check, and keep going. And Nate’s a lot mellower than I am. There is more panicking when I’m the master of my own project.

UD — What got you interested in the subject of quackery? Was it a specific patient or case, or a more general interest?

LK — My co-author suggested the idea of writing about quackery. And when he suggested it, I jumped. In medical school, we get no classes on the history of medicine, which is a shame! It’s fascinating to see where you stand in this long line of practitioners, and how the thought processes went before you.

UD — And about poisons? They are obviously central to the story in “A Beautiful Poison,” but they also occupy a sizable section of “Quackery.” It’s so curious that we know these compounds are deadly, use them in murderous ways, and yet turn to them again and again for tonics and cures. Why do you think that is, and what is it about poisonous compounds that makes them so fascinating and so important in human history?

LK — I believe it was Paracelsus who was credited with the concept of “the dose makes the poison” (which is not always true, we know now). However, the concept is fascinating — what can kill can cure, if you get it just right. It makes you realize we are surrounded by poison (imbibing too much water can kill you!), and isn’t that something? Since I was young, I knew about aspirin derivatives in willow bark and the help or harm that could come from foxglove plants. The usage of these good/bad sides to plants and elements is part of the tapestry of human history and pharmacology, and I never grow tired of exploring that in whatever writing I’m doing.

Poisons play a starring role.

UD — “Quackery” is a history of so-called cures, which also includes everything from bloodletting to “medicinal” alcohol. Yet it also seems relevant today. Do you see the book as simply a history or more of a reminder to this generation not to be fooled? Is there a particular snake-oil remedy today that you find worth calling out?

LK — The book absolutely is a reminder that though we may laugh at the past and think we’re so high-and-mightily forward-thinking about what works and doesn’t, we actually haven’t come very far when it comes to quackery. That was a huge revelation to me — the idea that every one of us is very susceptible, no matter what our background or level of education. Sometimes I think that the most powerful thing in the human landscape is bias and how it can have amazing effects that can also be quite terrible.

As far as a snake-oil remedy of today that drives me particularly bananas, I would have to say amber bead necklaces for teething babies. It’s an awful idea with no evidence to support. Choking-sized beads combined with tying anything around a baby’s neck is a recipe for heartache and disaster, and for a physiologic process that’s natural and self-limited? Please say no!

Deborah Blum, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, is director of the Knight Science Journalism program at MIT. She is the author of five books, mostly recently “The Poisoner’s Handbook.” Her sixth will be published in September.