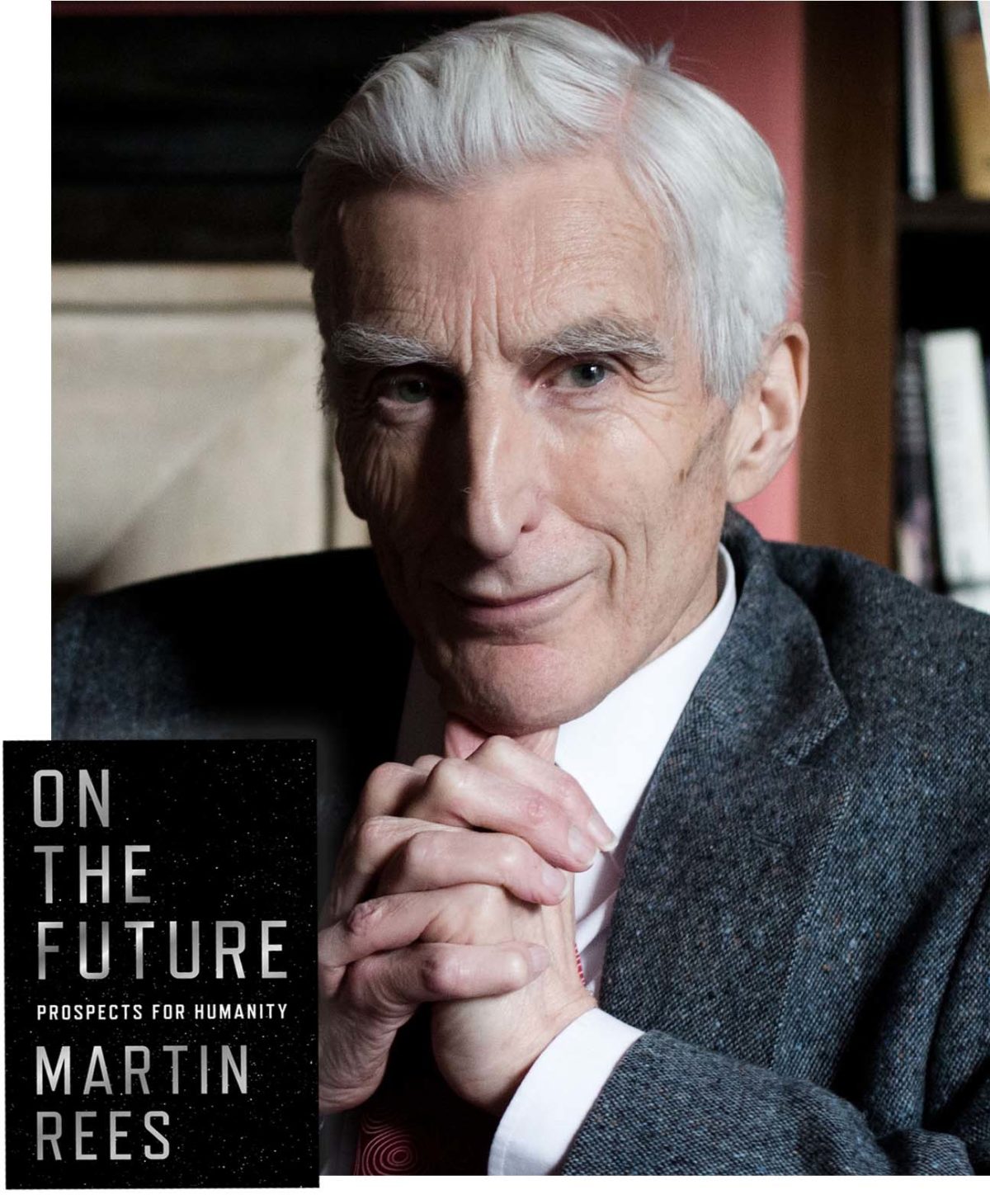

On Humanity’s Tenuous Future: Five Questions for Martin Rees

Martin Rees is used to thinking big. As Britain’s Astronomer Royal and former president of the Royal Society, he’s accustomed to dealing with cosmic questions and pondering the future.

“Many crucial issues need to be handled globally, and involve long-term planning,” says astronomer Martin Rees. “In contrast, the governmental focus is on the short-term.”

Visual: Nesta

During his long and distinguished career as an astrophysicist, Rees has also written an impressive collection of ambitious science books, including “Just Six Numbers: The Deep Forces That Shape the Universe,” “Our Cosmic Habitat” and “Gravity’s Fatal Attraction: Black Holes in the Universe.”

Fifteen years ago, he weighed in on another big subject with “Our Final Hour: A Scientist’s Warning: How Terror, Error, and Environmental Disaster Threaten Humankind’s Future in This Century — on Earth and Beyond,” in which he gave humanity only a marginal chance of surviving the 21st century.

But much has happened since then — some positive, some ominous — and his latest book, “On the Future: Prospects for Humanity,’’ reads something like an unofficial sequel, though less of a warning than a call to action. Both our survival and our future development are inextricably tied to science and technology, Rees tells us, and we can either choose to let achievements in those fields save us or destroy us.

For this installment of the Undark Five, I interviewed Rees by email to discuss his book and what has changed scientifically and culturally since he last took measure of our prospects for the future. Our exchange has been edited and condensed for space and clarity.

Undark: Fifteen years ago, you wrote “Our Final Hour,’’ which also dealt with the challenges facing humanity. Your new book, even down to the title, seems somewhat more cautiously optimistic about humanity’s survival. Would you agree with that assessment, and if so, what’s happened to change your thinking?

Martin Rees: It’s most unlikely that our species would be wiped out, but I think we’ll have a bumpy ride through this century, and we’ll be lucky to avoid major setbacks to our civilization — setbacks which, in our interconnected world, will cascade globally.

The concerns are of two kinds. The first is the risk of crossing ecological tipping points, due to the stresses imposed by the collective impacts of a larger, more empowered and more demanding population on land use, climate stability, and so forth. The second category of concerns are the threats stemming from the misuse, by error or by design, of new technologies such as bio, cyber, IT, and AI. These allow a small group, or even an individual, to trigger an event of catastrophic importance (the growth in cyber-attacks is a portent).

Because of the rapid advances in technology, we’re more aware of these risks than we were in 2003. There are well-intentioned efforts to regulate them, but these regulations are harder to enforce globally than drug laws or tax laws. Whatever can be done will be done by someone, somewhere. Efforts to minimize the risks will aggravate tensions between the goals of freedom, security, and privacy.

UD: You discuss ‘‘the depressing gap between what could be done and what actually happens,” and the endless impediments that allow problems such as hunger, public health crises, and poor education to persist. How do you think that those political, social, and cultural obstacles might best be overcome?

MR: Many crucial issues need to be handled globally, and involve long-term planning. In contrast, the governmental focus is on the short-term and the national or local. Moreover, the actions of large corporations are less and less easy to regulate by any government.

In tackling climate change, for instance, we are asked to make short-term sacrifices for the benefit of people in remote parts of the world 50 years (or more) into the future — to pay an insurance premium now, as it were, to reduce the probability of a worst-case climatic disaster during the lifetime of a child born today. Politicians are influenced by the press and by their inboxes. So these actions will slip down the agenda unless there’s public pressure. Governments will only prioritize these actions if pressured by a popular crusade. But that’s how all big social changes happen: abolition of slavery, black power, gay rights, etc.

UD: There seems to be a lot of gloom these days, with people worried about the environment, political and social divisions, and increasing authoritarianism. Yet, as thinkers such as Steven Pinker have documented, humanity’s actually better off than ever according to many objective measures, as a result of science and technology informed by Enlightenment ideals. Do you agree with that optimism?

MR: Steven Pinker is one of our most influential public intellectuals. I’ve read all his books. In the last two, he has quantitatively documented how people’s lives have improved compared to those of our predecessors. There have been gains in health, life expectancy, literacy, and so forth. And this wouldn’t have happened without technology.

Pinker is right to emphasize that for most people, this is a better time to be alive than any previous era. But there are two reasons why I don’t share his optimism, projecting forward, and why I’m a political pessimist, despite being a techno-optimist. First, there is a new class of threats — low probability but with immense disruptive consequences — to which society is increasingly exposed with the advance of technology, especially by bio and cyber. We are lulled into complacency because such events haven’t yet happened — but even once will be too often.

Secondly, I don’t share Pinker’s implied view that our institutions are ethically superior to earlier generations. Medieval people may have generally led miserable lives, but there was little that could have been done to improve them. Today, technology offers huge benefits — it could, optimally deployed, provide a good life for all 7.5 billion of us. But it’s not doing so: Indeed there’s a bigger gap between the way things are and the way they could be than there ever was in the past.

UD: Do you think it’s counterproductive to place too much hope in the notion of colonizing space? Is it a task best left for farther into the future, when it can be done by AIs or new forms of humans bioengineered for the space environment?

MR: I’d like to give a nuanced answer to this. The idea of mass emigration to Mars is espoused by two people who I immensely admire: by my late colleague Stephen Hawking, and by Elon Musk. But I think this is a dangerous delusion. There’s nowhere in the solar system as clement as the top of Everest or the South Pole. There’s no

“Planet B” for normal risk-averse people: We need to solve our problems here, and secure a sustainable home on this planet.

Nonetheless, I’m an enthusiast for manned space exploration — not by the masses, nor even by space tourists, but by a few thrill-seeking pioneers who are prepared to go on space voyages that are riskier and cheaper than any that it would be politically feasible for NASA to do.

The reason for cheering on these adventurers is this: they will be ill-adapted to their Martian habitat and will have every incentive to use all the genetic and cyborg techniques — techniques that will, one hopes, be heavily regulated on Earth on prudential and ethical grounds — to adapt to their hostile environment. They will be beyond the clutches of the regulators, and will have a greater incentive to use these techniques than those of us who are well-adapted to living on the Earth and happy to stay there.

But the progeny of these pioneers will quickly evolve (via secular intelligent design, far faster than Darwinian selection) into a new species — maybe flesh and blood, but more likely electronic. And then they’ll no longer need an atmosphere, and may prefer zero gravity, so could fly off into space — and interstellar voyages wouldn’t be daunting to near-immortal creatures.

UD: You discuss the possibility of science reaching the limits of understanding by our poor biologically evolved brains. Will humanity’s continued survival depend upon our transition to some kind of nonorganic electronic form? If that’s the case, when do we stop being “human” and become something else?

MR: There may indeed be crucial aspects of physical reality that will always perplex humans, or indeed that we may never be aware of. But AI will be a huge help. For instance, string theories envisage a huge variety of possible structures in a space of 10 or 11 dimensions. Consequently, even if some variant of the theory applies to our real world (in that it can predict some of the key numbers and ratios of physics) it may be far beyond human powers to do the requisite calculation. But AI could maybe do it, and thereby test whether a particular theory is correct.

A new species, posthumans, will surely emerge — though probably away from the Earth. The outcomes of future technological evolution could surpass humans by as much as we (intellectually) surpass slime mold. What about consciousness? Philosophers debate whether this is peculiar to the wet, organic brains of humans, apes, and dogs. Might it be that even the most powerful electronic intelligences will still lack self-awareness or inner life? Or is consciousness a phenomenon that’s emergent in any sufficiently complex network?

Some say this question is irrelevant and semantic — like asking whether submarines swim. But I don’t think it is. The answer crucially affects how we react to the far-future scenario I’ve sketched. If the machines are zombies, we would not accord their experiences the same value as ours, and the post-human future would seem bleak. But if they are conscious, we should surely welcome the prospect of their future hegemony.

Mark Wolverton is a science writer, author, and playwright whose articles have appeared in Undark, Wired, Scientific American, Popular Science, Air & Space Smithsonian, and American Heritage, among other publications. His latest book “Burning the Sky: Operation Argus and the Untold Story of the Cold War Nuclear Tests in Outer Space” was published in November. In 2016-17, he was a Knight Science Journalism fellow at MIT.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Tenuous is not a good word: While I’ve not done computer models, (many things at present are unmodelable) I can visualize various scenarios:

Economic

* Total collapse of the international monetary system, leading to a long term slump in trade.

* Individual nation’s economic collapse coupled with collapse of their social institutions.

* Reversion of the EU to individual nations, balkanization of nations as central governments fail.

Ecologic

* A planet that is 2.5 to 6 degrees C warmer than today.

* Many tropical regions becoming unlivable.

* Many ecologies collapsing or undergoing radical change as some critical species dies out.

* Wide spread decrease in range extent for many species.

* Extinction of many species.

Humanitarian.

* 1-2 billion refugees from tropical regions.

* 2-3 billion refugees from coast lines.

* Extensive crop failures and famine from shifting rain patterns.

* War over dwindling food and water.

2100 may dawn with only a billion people left alive.

Extinction? Not hardly.

I believe the only risk to humankind is the exact same risk it has always faced: Failure to coexist with our fellow human.

I see the history of the Western (our) world in 500 year incremented cultural epochs. Our current Western society, dating from 1517 can be described as the Protestant Reformation era. As with all Western Cultural epochs, it includes many phases and contradictions, but one cannot understand contemporary Western Culture without giving due credit to the influence of Martin Luther. Yes, of course Luther was heavily influenced by Greek philosophical perspectives, but Luther, along with the contemporary rise of the printing press, enabled a new human culture to flourish. The Reformation, of course, brought TREMENDOUS conflict and tumult. The 30 Years War in Europe, for example, which left millions dead. With profound cultural change comes conflict, and violence.

The 500 year Protestant Reformation society, as defined by its Faith, morality, and institutions, is collapsing. In its wake, we observe the rising of a new Internet culture. The transition is gradual, of course, but our septuagenarian great-grandchildren will fully understand what has been gained, and what has been lost, in transition.

It’s funny, how so many thinkbwe have a population problem, when the populatuon growth is caused by overproduction of food.

This idea of interplanetary post-humans is fascinating and I believe will shape “lowly” in a similar way such as when a famous person likes your tweet. We will increasingly have ambient relations with non-physical “beings”. Perhaps this dates back to empowering dolls or toy trucks with an animated life. The definitions of what life or intelligence or awareness is and will become is a cultural process and so these interplanetary explorers will be willed into a certain humaness, even if they are not quite the wet sentience that we are used to.