Talking it Out: The Effort to End Female Genital Mutilation in Ethiopia

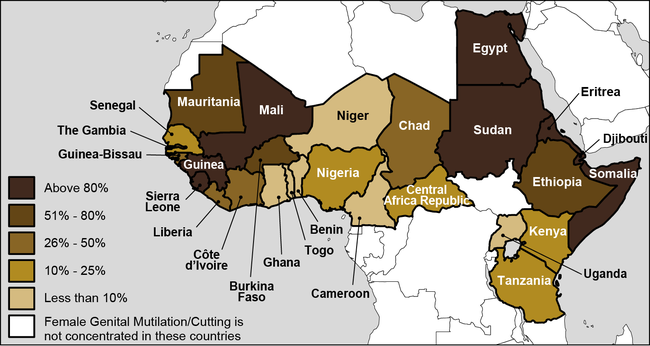

Worldwide, it is estimated that 200 million girls and women have undergone female genital mutilation, a bloody ritual involving the removal or non-medical destruction of the external genitalia. The rationale for the practice, which remains common in parts of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, and is globally recognized as a human rights violation, varies from region to region, though it is rooted in cultural efforts to govern and control female sexuality.

The practice can take a number of forms, from clitoridectomies, which involve the partial or total removal of the clitoris or, rarely, the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris; excisions, which remove both the clitoris and the labia minora and in some cases the labia majora; and what’s known as infibulation, which involves the narrowing of the vagina by cutting and repositioning the labia, sometimes with stitching, to form a seal over the vaginal opening.

In the short term, these and other associated practices — which include all manner of “pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterizing” the female genital area, according to the World Health Organization — result in severe pain and bleeding, infections, shock and sometimes death. Longer term, women face a lifetime of disfigurement and a host of health problems, including urinary and childbirth complications, painful menstruation, sexual dysfunction, and associated psychological problems.

In 2015, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals included efforts to stop female genital mutilation worldwide, and Ethiopia itself officially criminalized the practice more than a decade ago — but breaking down cultural barriers has taken time. Four years ago, acknowledging that the practice remained widespread despite the ban, the Ethiopian government launched a national plan to stop female mutilation. It followed up in 2014 with a pledge at the U.K.- and Unicef-sponsored Girl Summit in London to end female genital mutilation entirely by 2025.

Tsehay Gette, a program officer with United Nations Population Fund in Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa, suggested that these efforts are working. “There is promising progress to reach the goal,” she said.

To be sure, the practice persists in many parts of Ethiopia, and much work remains to be done to make good on the government’s promise. But here in the southern region of Kembatta Tembaro, where the clitoris and inner and outer labia was traditionally removed with crude blades, a remarkable turnaround has taken place — driven in part by indigenous nonprofit organizations like KMG-Ethiopia (short for Kembatti Mentti Gezzima-Tope, or Kembatta Women Standing Together). Since KMG began work here in 1998, the acceptance rate of female genital mutilation among the region’s population dropped from 97 percent to less than 5 percent over eight years, according to a Unicef report.

More recently, the KMG model, which focuses on “community conversations” where villagers gather every two weeks to discuss important social issues, including female genital mutilation, with help from trained Ethiopian facilitators, has prompted other nonprofits, government health workers, United Nations agencies, and religious organizations to join efforts to reduce the practice across Ethiopia. Nationwide prevalence of genital mutilation among females 14 to 49 years old in Ethiopia is down from 74 percent in 2005 to 65 percent in 2016, according to a Unicef report. Among girls and women age 15 to 19 years old, prevalence is 47 percent.

Of course, public health and human rights advocates emphasize that tens of millions of women and girls are still being subjected to cutting, and this week President Donald Trump announced plans to eliminate all U.S. funding for the United Nations Populations Fund, which works in dozens of countries to improve public health outcomes — including curbing rates of female genital mutilation.

Still, if the sort of cultural reform that has unfolded here in Kembatta Tembaro can happen elsewhere in the country — and indeed, around the world — new generations of young girls might well be spared this painful and dangerous ritual.

Following are eight short interviews with residents of Kembatta Tembaro and the nearby district of Bona. The diversity of voices — mothers, fathers, sons and daughters, village elders, and religious leaders — underscore the need for a community-wide commitment to change. They also reveal how empowering women and girls in general can lead to greater social and public health outcomes for everyone. The interviewees here were asked through an interpreter to share their thoughts on why they abandoned female genital mutilation, and to explain how their communities, over time, managed to change from within.

In Kembatta, 28-year-old Mihret Ayele is the only one of three daughters in her family who did not undergo genital mutilation. Her parents both participated in KMG’s community conversations and eventually changed their minds about the practice. “Because of the community conversations, they did not worry about me getting married as an uncut woman,” said Ayele.

When asked whether her partner wanted to marry a cut woman, Ayele explained that her husband, age 35, also attended the community conversations. He learned about the medical dangers and in the end, did not favor the practice.

As it stands, childbirth was more dangerous for the previous generation. The World Health Organization notes that risks of postpartum hemorrhage, obstetric tears, prolonged labor and other complications increase with the severity of genital mutilation, and Ayele recalled her own mother giving difficult birth to a sibling. “We were crying for our mother, grieving and worrying,” she remembered.

Ayele herself has two children, ages 10 and 7. She thinks escaping genital mutilation helped her to avoid complications during what were two quick childbirths. “If I were cut, I would have encountered a lot of problems when giving birth.”

Ayele cited another benefit of rejecting female cutting: “There is better love between me and my husband,” she said plainly, adding that forced marriage and domestic violence have also decreased within the community. “Women’s rights were not respected in this area before,” she added. “There are a lot of changes now.”

In a survey of villagers in Kembatta, 85 percent had participated in community conversations, according to the 2008 Unicef report — a crucial number. Reaching men and boys is critical to changing perceptions of female genital mutilation.

I met Mehrun Abebe, an 18-year-old student, as he was crossing a bridge over a small river in the woods. This was a bridge that KMG helped to rebuild when it started working in Kembatta, thereby gaining people’s trust. Abebe had also participated in the local community conversations, where the towering young man learned about the excruciating pain and health complications of female cutting.

A generation ago, women and men hardly spoke together publicly at all. And no one, not even girls and women, discussed the taboo subject of female genital mutilation. But in community conversations, people discussed the effects of the practices, as well as other sensitive social issues. “There is bleeding when females are mutilated. I have heard about many experiences of cut women like my mother and the consequences of being cut,” said Abebe.

These sorts of frank exchanges have been a key element of the campaign to change longstanding traditions with deep roots in the local culture. And the discussion facilitators “are not coming in and saying, ‘Do this, don’t do that,’” Abebe says. “They just guide the community to identify their own problems, discuss and provide solutions.”

As it now stands, Abebe says he prefers to marry an uncut woman. “Even my friends nowadays are looking to marry uncut girls rather than cut ones.

“I don’t have a sister,” he added, “but if I had one I’d never allow her to be cut.”

Wolde Gebremichael, 45, recalls that the initial conversations within his community about female genital mutilation were strained. “In the beginning it was difficult to change people’s attitudes,” he said. “They were not accepting at first.”

Ensuring that both women and men were able to participate in equal numbers was important, as was getting church leaders like Gebremichael on board. (I met Gebremichael as he was returning from church on Sunday.) Before groups like KMG start working in a community, they must reach out to influential people, including local religious leaders and government administrators. In some instances, religious leaders reported being surprised to learn that genital mutilation is mentioned in neither the Bible nor the Koran, and that it has no religious mandate.

The results of this kind of knowledge sharing are easy to identify, Gebemichael says — including a healthier population of women. “Before, I knew so many mothers who died while giving birth. There was a lot of bleeding and health related complications.”

There have also been major social changes, especially in relationships between men and women. Previously, “the wife just brought the food, gave it to her husband and went back to the kitchen. Women were like cattle,” he remembered. “Now women and girls come together in church, public areas and discuss equally with their husbands.”

He added that before, men kept their family’s money in a locked box. “The wife never had the right to touch that money. Nowadays, the wife and husband try to use money equally.”

Bekelech Balecha, a 45-year-old farmer, welcomed community conversations when KMG started working in Bona. “I was the one clapping; I accepted them because I knew all the problems,” she said. Balecha was 23 when she was cut without anaesthesia. Her family was one of the few in this community that did not have their daughters undergo genital mutilation when young. Her father worked with foreign missionaries and knew that the practice was harmful. But Balecha voluntarily underwent the procedure before marriage because her now-husband insisted on it. “For a week I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t even eat, couldn’t walk,” remembered Balecha. “It was the most horrible experience of my lifetime.” Later, she experienced complications during three days of childbirth. If not for a Swedish clinic nearby, she could have died.

Female genital mutilation was a taboo subject, Balecha said — particularly in conversations between women and men. But the community conversations emboldened Balecha to speak out against the practice in churches and women’s associations. “I can even talk in front of 50 people. I really don’t mind. I can present myself first as evidence of this issue. I can even say I stopped having sex with my husband after the age of 35,” she said frankly. “I never had any pleasure from sex.”

At first, circumcisers and community members opposed change, she recalled. “People said that if a girl is uncut she becomes useless, she can destroy the household, property, even that she won’t have a husband.” But after ongoing conversations, people began changing their minds.

Balecha ultimately forbade her daughter, 12-year-old Tezerash Tesfa, from being cut — but Tefsa had also been learning about the practice through girls’ clubs organized by KMG. “We’ve been told that if girls don’t go through circumcision she will be free from complications. Her body is normal, not damaged,” she said. “I’m whole and healthy.”

Tesfa is tall and lanky and wears shiny athletic shorts – quite unusual for a girl in rural Ethiopia. She plays soccer as part of her girls’ club. There are 50,000 girls in these clubs in southern Ethiopia. They promote sports, crafts and other life skills to reinforce messages of self-esteem, empowerment, and health.

“In our community, girls and women are discriminated against. I learned that I have to show that I am equal to boys and I can do whatever boys do. I started playing sports and developed my football skills. Now I’m one of the good players.”

Her mother recalled that not long ago, families kept girls at home and didn’t let them go to school. “When we first heard about girls playing soccer, we laughed.”

But girls did start to play and participate with boys, and this has helped to reinforce their wider autonomy within the community. “We recognized it gave them power and self-confidence. It was a breakthrough for us,” Balecha observed.

She mentioned that her daughter would be playing in a soccer tournament the next day. “I will be there early in the morning with my banners to support my girl and other girls there,” said Balecha. “We’re working more on girls’ soccer and we can share our experiences with neighboring districts and other areas.”

Beyebo Eresado, a 50-year-old farmer and village elder, recalled that when KMG started its outreach program here, his initial reaction was disbelief. The community genuinely believed female genital mutilation was part of their culture and benefited the girl, he said.

Indeed, Eresado’s older daughter was already cut by the time the reform movement reached his community, but he decided his youngest daughter shouldn’t undergo the procedure. He observed that his younger daughter, today age 27, is open and confident and has a “peaceful” relationship with her husband. The other daughter, 30, is not confident and has a strained marriage, Eresado says.

He adds that in years past, “most women were just working in the kitchen, not eating with us. Now we are eating together. They speak loudly and equally with us.” And that shift has yielded dividends well beyond protecting the public health of women and girls, Eresado said.

“Now they are working with us, generating additional income for the family. We have a mutual purpose.”

In addition to talking about female genital mutilation, community conversations often broach a range of social issues, from unwed pregnancies to exorbitant dowry prices that lead to bride abductions and domestic violence, according to Adane Tula, a farmer in Bona district.

Tula, 33, is the father of three daughters. He says he intended to cut all of them, but all three remain uncut today, and Tula says he now understands that the practice likely plays a role in the difficulties that he and his wife experience with sex.

This sort of candid discussion about private matters was strange at first, admitted Tula. But his perception of women gradually changed. “Day by day, we learned a lot,” he said.

“Women brought up very important issues and ideas. We started to admire our wives and female community members. Before, we just kept our wives at home. We never exchanged ideas. Now we even regret what we did in earlier times.”

Abebech Yacob was 14 years old when she was cut. “They tied my legs with rope,” she recalled. “I was bleeding almost 12 hours. I was almost dead.” Psychological trauma from pain and shock is another consequence of genital mutilation, says the World Health Organization.

Years later, she lost two of her children during childbirth. Yacob had no idea that female genital mutilation could cause childbirth complications. “Even when I lost my boys, I thought evils spirits took them. I said, ‘Please God, why did you take my boys?’”

Those misconceptions were easily dispelled once discussions of the hazards of genital mutilation began to unfold in earnest in Kembatta Tembaro. “It was not a big challenge for me to accept because I experienced this, so I changed my mind very fast,” she said, “and I immediately started educating others.”

Yacob highlighted a program where KMG gave valuable livestock and training to women. She joined a women’s cooperative in her village and eventually became its head. “Before I was a member of this association, I didn’t have anything. Economically, I was disadvantaged,” she said. And owning an ox changed Yacob’s status in the community. Income earned from renting the ox for farm work let her send her children to school.

Yacob reflected on her daughters’ futures. They will never go through what I had to go through. Probably they will become more confident and powerful,” she mused. “I know these things from my personal life so I’m now educating the community to stop genital mutilation, because I’m a victim of it.”

Amy Yee is an award-winning journalist who has written for The New York Times, The Economist, and NPR. She is a former correspondent for The Financial Times based in India and New York. This story was produced with help from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

FGM is an unhealthy traditional practice inflicted on girls and women worldwide. FGM is widely recognized as a violation of human rights, which is deeply rooted in cultural beliefs and perceptions over decades and generations with no easy task for change.Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2012 Jan-Jun; 2(1): 70–73.

doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.96942

PMCID: PMC3507121

PMID: 23209995

An Overview of Female Genital Mutilation in Nigeria

TC Okeke, USB Anyaehie,1 and CCK Ezenyeaku

39\116 Maneerin. Bangsaen

Muang Chonburi

I am writing a novel where the consequences of FGM prove lethal and a child dies from complications. I wish to portray the police and community working together to put an end to the practice. How likely is it that both men and women would attend the presentations made by the police and social services in the UK, particularly Bristol.