Agrandmother with bronzed skin and a craving for salt; jars of pituitaries collected from cadavers for their growth hormone; transplanted ape testicles. These wildly disparate stories and images are linked by a common factor: the hormone.

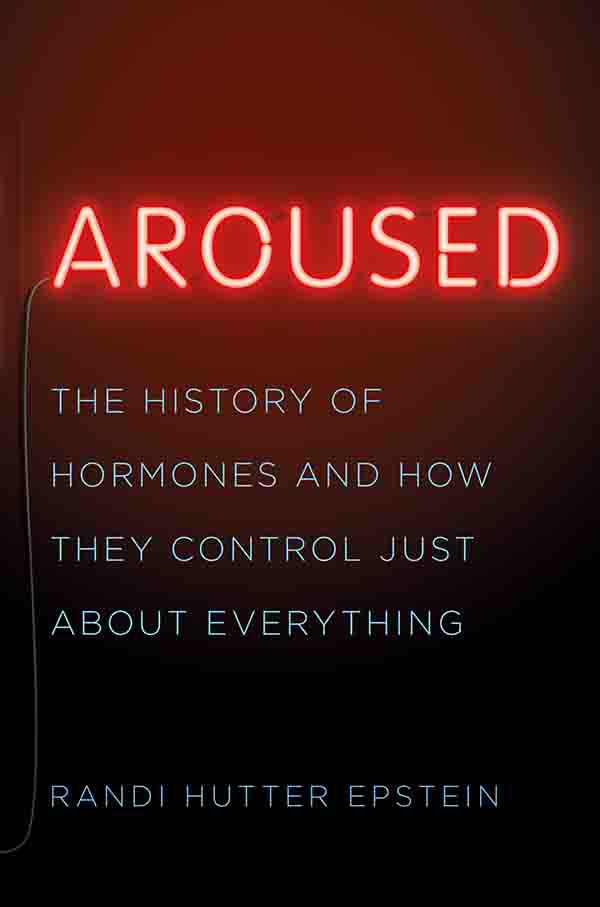

BOOK REVIEW — “Aroused: The History of Hormones and How They Control Just About Everything,” by Randi Hutter Epstein (W.W. Norton, 336 pages).

So we learn in “Aroused,” an eye-opening new book that traces the history of endocrinology through a sequence of crisp, meticulously researched, and often surprisingly funny tales from the turn of the 20th century to today.

Though hormones have entered common parlance — we have growth hormone and sex hormones and hormone replacement therapy — it was not always this way. Randi Hutter Epstein, an accomplished author who has a medical degree and a master’s of public health, illuminates more than a century of false starts and research gains as she explains the ways these chemical messengers control the daily work of our bodies. At the same time, she leaves us wondering how much of our current understanding of hormones is in fact “true” and how much may ultimately be disproved.

This is a novel contribution. While most of the literature on hormones has been confined to medical text or limited to a single hormone (estrogen, for example), Epstein’s approach is wide-ranging. Consider this story. The year was 1924, and two teenagers in Chicago bludgeoned a younger boy to death. The new field of endocrinology was exploding at the time, and their lawyers proposed a provocative theory to avoid the death penalty: Hormones were at fault. After extensive X-rays, interviews, and measures of metabolism, doctors testified that the teenagers had severely impaired hormonal glands and had committed the grisly murder under the influence of hormones gone awry. They were sentenced to life in prison.

Epstein gives an enthralling account of Eugen Steinach, a physiologist in 1920s Vienna, who made his name by promoting the vasectomy as a risk-free, all-natural rejuvenation treatment to boost intellect and libido. The premise was that “blocking the exit of manly juices … prompted a congestion of them, much the way a traffic jam causes a pile-up of cars.” The idea sold, and men came in droves for the (ultimately unsuccessful) procedure: a testament to the powers of placebo and publicity.

Despite her light tone, Epstein acknowledges the darker side of the growing interest in these potent but incompletely understood chemicals. In one memorable chapter, she tells the story of Brian Arthur Sullivan, born in the 1950s with ambiguous genitalia (a small penis and unusually shaped scrotum). Doctors had no idea what to do, so the family took the baby to specialists at Columbia University who were studying how hormones might lead to abnormal genitalia. The doctors proceeded to do exploratory abdominal surgery to get a firsthand view of the reproductive organs, and three weeks later they sent young Brian home with a shocking diagnosis: inside the baby’s abdomen they’d found a uterus, a vagina, and ovaries. The abnormal penis was in fact a clitoris, which they had gone ahead and amputated. Brian was a girl and should be treated as one, immediately.

So Brian became Bonnie. Her trucks were replaced with dolls and her pants became pink dresses. When she was 8, she returned to the hospital for another sequence of surgeries to remove remaining testicular tissue. Her doctors assured her parents that their daughter would grow into a happy, successful woman. She would be normal.

Almost needless to say, the transition didn’t go as smoothly as advertised. Epstein is at her best when telling human stories like this one. Her descriptions of the adult Bonnie (now Bo) are evocative: We travel to Bo’s “cozy home in a quiet rural town in Sonoma County,” looking with gentle interest at the old leather album of baby pictures, the only one saved from her early months as Brian. A curious, compassionate, often witty guide, Epstein offers a different anecdote in almost every chapter, and I found myself more engaged by the tales of these individuals than by the history and science their stories are used to illustrate.

I would have liked to delve more deeply into the reality of Brian’s childhood and Bo’s adulthood. I also wondered what life was like for Jeff Balaban, whose parents collected jars of cadaver pituitary glands so he could be injected with growth hormone. And I found myself looking for clues to Epstein’s own experience of researching and writing. For instance, there’s a great scene in which a doctor offers her oxytocin candy. Though I closed that chapter having learned a great deal about oxytocin, I wanted to know more: what Epstein and the hormone-pushing doctor talked about, what if anything she said when she didn’t feel the promised effects. That I was this interested in hearing more about Epstein the narrator is a testament to her voice and likability.

Of course, these personal moments might not be the highlight for all readers. Maybe for you it will be the opportunity to learn about primitive experiments, bold and promising at the time but bordering on insanity in hindsight. Or perhaps you’ll favor the accessible prose that brings clarity to complex scientific concepts, a great strength of Epstein’s writing. Whatever it is that draws you, once you give yourself over to her expertly guided tour, you may never again think about your hormones in quite the same way.

Daniela Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and the author of “You Can Stop Humming Now: A Doctor’s Stories of Life, Death, and in Between.”