When Scott Kelly was 18 years old, he bought a book. To read. For fun.

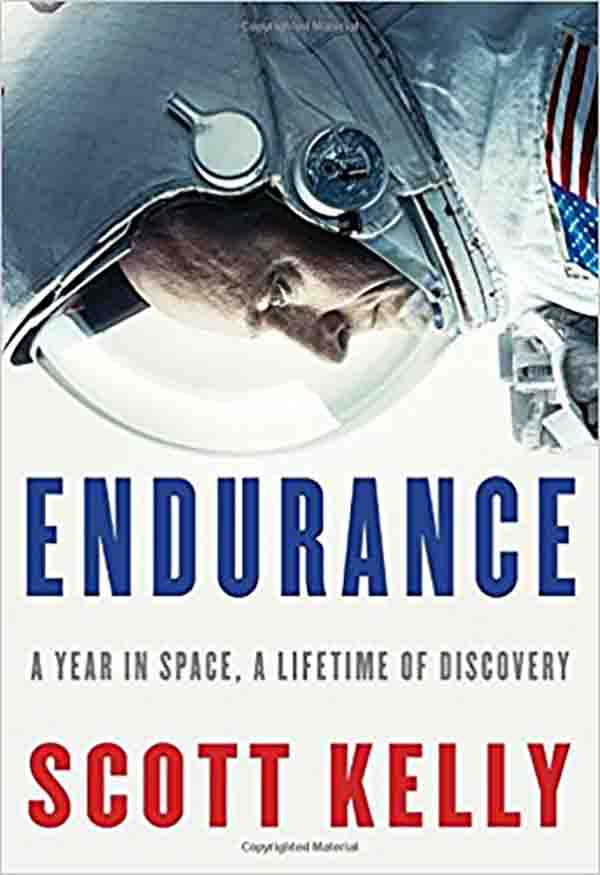

BOOK REVIEW — “Endurance: A Year in Space, a Lifetime of Discovery,” by Scott Kelly (Knopf, 387 pages).

This was an exceptional moment. He had been a distractible, diffident student who stared out of classroom windows. He was something of a knucklehead, he admits; when he applied to college at the University of Maryland, he didn’t notice that he had accidentally applied to attend the Baltimore campus instead of the main campus in College Park. No football games for him!

The book was “The Right Stuff,” Tom Wolfe’s history of the Mercury astronauts. The first pages gripped Kelly, with their vivid description of a test-flight disaster and the charred pilot, his head knocked to pieces “like a melon.” He read the book straight through. And when he was done, his life had purpose: He wanted to be an astronaut.

Lots of people want to be astronauts. Very few actually do it. The path of Scott Kelly into space, and his four spaceflights, including his last marathon mission of 340 days on the International Space Station, are the story of “Endurance: A Year in Space, a Lifetime of Discovery,” which he wrote with Margaret Lazarus Dean.

Growing up in West Orange, New Jersey, Scott Kelly and his twin brother, Mark, were adventuresome — even foolhardy. “We both got stitches so often we sometimes would have the stitches from the previous injury removed during the same visit new stitches were put in,” he tells us. By exploring space, he could combine his love of challenge and adventure with real purpose.

He would learn to study. He would learn to focus on goals and achieve them. He would transfer to a school he actually intended to attend, the State University of New York Maritime College. And he made his way through a funnel of achievements: Chosen as a Navy pilot, then as a fighter pilot, he learned to land fighter jets on the rolling deck of an aircraft carrier at night — a type of flying even more harrowing than landing a space shuttle. He became a test pilot and, finally, an astronaut.

And here’s the fun part: He was selected for the same astronaut class as his twin brother. When he took that last flight, he underwent regular and rigorous medical tests in parallel with Mark so scientists could study the effects of space on the body with a control subject back on Earth.

As a writer, Scott Kelly has an irreverent voice, skipping the earnest and constrained tone that pervades many astronaut memoirs, inspirational though they may be. Gruff and sometimes grouchy, he is also — and note well, those of you thinking of buying this book for your space-crazed kid — entertainingly profane. When he tells the story of being assigned to his first fighter squadron, VFA-143, nicknamed “The World Famous Pukin’ Dogs,” he does not shy from relating what a senior officer told him: “This squadron is about three things: flying, fighting, and fucking, and not necessarily in that order.”

That willingness to work blue carries over into his time as an astronaut — as when he confesses to having said “fuck” while struggling with a piece of hardware during his second shuttle flight. “Hot mic!” called out Tracy Caldwell Dyson, a fellow astronaut on that mission, meaning that his words were going out live via NASA TV. “Shit!” he responded.

His longest mission, the near-year aboard the station, is presented as a test of his own endurance. The title of the book is a reference to Alfred Lansing’s “Endurance,” about Ernest Shackleton’s 1914 effort to cross Antarctica. He kept a copy of that 1959 work with him aboard the space station, reading it to gain perspective. “Sometimes I’ll pick up the book specifically for that reason,” he writes. “If I’m inclined to feel sorry for myself because I miss my family or because I had a frustrating day or because the isolation is getting to me, reading a few pages about the Shackleton expedition reminds me that even if I have it hard up here in some ways, I’m certainly not going through what they did.”

Despite the advanced communications that allow calls from space to be patched directly to the cellphones of family and friends, the isolation is real and insurmountable. When his sister-in-law, Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, was shot in a Tucson parking lot in January 2011, he was in orbit. Thirteen other people were wounded that day and six were killed. Scott Kelly could phone home, but he could not be there. He was fixing the station’s toilet when he got the news.

As important as space exploration may be, living and working there can be a grind. The equipment vital to life, like the toilet, goes on the fritz. Repairs can be agonizingly difficult. High carbon dioxide levels on the station induce headaches and fuzzy-headedness. The schedule is punishing, and spacewalks are exhausting. Coming back from his long mission involved days of misery as his body began adjusting to gravity again, and it was months before he felt fully recovered.

Toward the end of his account, he lays out the things he missed during his time in orbit. It is a long list that gives a sense of what you don’t experience in space, and it puts you there in a powerful and lyrical way. A small part of it:

I miss cooking. I miss chopping fresh food, the smell vegetables give up when you first slice into them. I miss the smell of the unwashed skins of fruit, the sight of fresh produce piled high in grocery stores. I miss grocery stores, the shelves of bright colors and the glossy tile floors and the strangers wandering the aisles. I miss people…I miss showers. I miss running water in all its forms: washing my face, washing my hands.

When he gets home, he tells us, he walked straight through his house, into the backyard, and jumped into his swimming pool with his flight suit on.

For all that, he clearly loved his time in space, the camaraderie with colleagues from NASA and Russia and the other nations involved in the space program. The International Space Station, with its cupola that gives sweeping views of the planet below, brings perspective to human events, as he said in a speech he gave calling for a moment of silence for Gabrielle Giffords and the other victims of the Tucson attack:

As I look out the window, I see a very beautiful planet that seems inviting and peaceful. Unfortunately, it is not.

These days, we are constantly reminded of the unspeakable acts of violence and damage we can inflict upon one another. Not just with our actions, but with our irresponsible words. We are better than this. We must do better.

Not bad for a kid who used to stare out the window. Clearly, some windows are more meaningful than others.

John Schwartz writes about climate change for The New York Times. On an earlier beat, as a science reporter covering NASA, he interviewed Scott Kelly a number of times, including once in Star City, Russia.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Just finished the book. I’ve read several reviews so that I can more intelligently lead our book club discussion. FYI, your review was the best. You zeroed in on what was important. Thank you.