Close your eyes and picture an elephant. Most likely, what comes to mind is a big-eared bull with gleaming white tusks, towering majestically in a vast African grassland. Yet an equally valid image might be a more petite animal with a speckled trunk, comically small ears, a bulbous forehead, and pint-sized tusks (if any), slogging through an Asian city or logging camp with a human rider on its back.

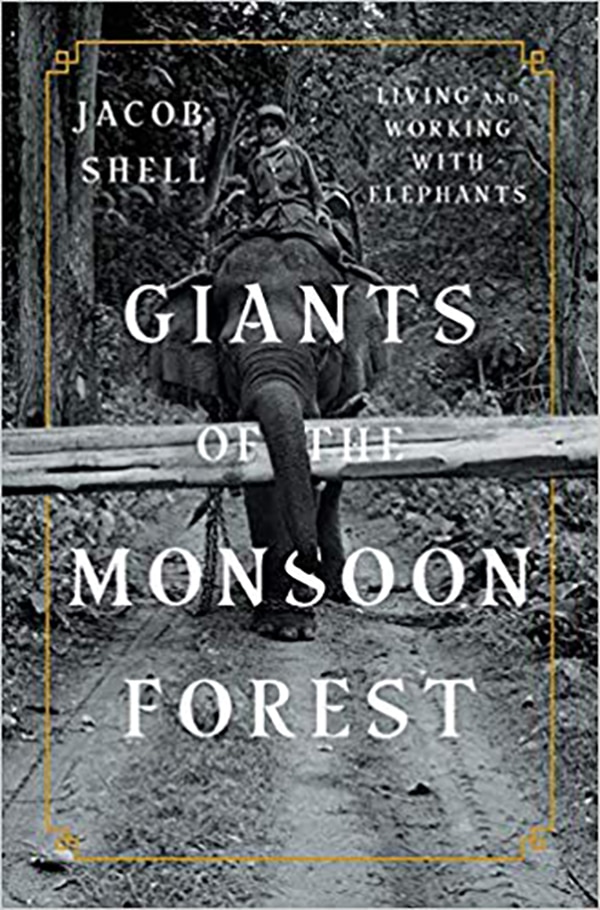

BOOK REVIEW — “Giants of the Monsoon Forest,” by Jacob Shell (W.W. Norton, 288 pages).

African elephants may hog the spotlight in the Western imagination, but Asian elephants are an equally fascinating — and far more imperiled — species. An estimated 400,000 to 500,000 elephants still roam Africa, while just 40,000 to 50,000 remain in Asia. Shockingly, up to a third of them live in captivity.

In “Giants of the Monsoon Forest,” Jacob Shell, a professor of geography and urban studies at Temple University, transports readers to the jungles of Myanmar, India, and Indonesia to encounter Asian elephants and the people who work with them. Taking a more anthropological than ecological approach, Shell delivers a deep dive into the surprisingly complex relationship between our species — from 3,000 years ago up until today. In the process, he shows how both Asian elephant populations and the millennia-old human cultures they have supported and enabled are coming under increasing stress from the forces of modernization.

In Asia’s remote monsoon forest communities, elephants are lifelines, providing a means for earning a living through logging and a method for transporting people and goods through difficult, frequently flooded terrain. Shell argues that this mutually beneficial alliance has allowed elephants to eke out survival in one of the most densely populated regions of the world. “By associating themselves with these humans and their forest-based economy, Asian elephants boost their own likelihood of inhabiting the sort of landscape in which they tend to be healthiest and happiest,” he writes. In other words, Shell argues, elephants seem to have figured out that they can either work with people — or else get displaced and killed by them.

Unlike livestock or domestic pets, however, elephants have never been selectively bred by humans. Instead, new elephants are recruited for work primarily through capture in the wild. Once broken in by their mahouts — the elephants’ (almost always male) handlers — the animals are usually allowed to roam in the forest at night, albeit with loose chains binding their front feet to prevent them from getting too far. This 9-to-5-like arrangement relieves the mahouts of responsibility for feeding their captives (Asian elephants eat up to 600 pounds of vegetation per day) and also gives the animals an opportunity to spread their genes through nocturnal trysts with wild individuals.

Shell doesn’t dwell for long on the unsavory side of the human-elephant partnership, and initially I found that difficult to accept, both from a conservation and animal-welfare point of view. He does touch, for example, on the cruelty that wild baby elephants are subject to after capture, including being tied up for months on end and starved into compliance. And just as Shell provides many touching and impressive examples of the strong bond that develops between elephant and mahout, he also notes that captive elephants can display aberrant behavior indicative of the psychological trauma they endure, including killing their human companions, mating with their relatives and — in one horrific example — digging up and eating bodies from a local cemetery.

In the end, though, Shell makes it clear that Western indignation is not enough to save Asian elephants or their habitats. Elephant handlers, he writes, “have a great deal to teach concerned outsiders about how human beings, as morally imperfect creatures, can act as guardians rather than destroyers of the forest’s last giants.”

But as indispensable as they are for life in Asia’s remaining monsoon forests, the elephants still face ample threats. Chief among them is deforestation, Shell rightfully points out. While Myanmar remains one of the most forested countries in Southeast Asia and the most elephant-rich, it has nevertheless lost 20 percent of its tree cover since 1990. Much of the elephant-aided logging taking place today by both the government and Myanmar’s ethnic armed groups is illegal and unsustainable, according to a recent report by the London-based Environment Investigation Agency. Shell argues that mahouts traditionally practice rotating forestry, leaving logged areas alone for decades to allow for regrowth, but history and statistical data show that profit can easily trump sustainability.

Meanwhile, the growing problem of poaching of Asian elephants for their skin, coveted for use in traditional Chinese medicine and fashioned into jewelry, is only mentioned in passing and could have been explored more deeply in this otherwise illuminating account.

As Southeast Asia’s forests continue to fall and communities continue to urbanize, the future of elephants and those who handle them grows increasingly uncertain. A recent study in the journal PLOS One, for example, found that Myanmar’s mahouts are younger and more inexperienced than they were in the past, and that they change elephants more frequently — threatening the transfer of traditional knowledge as more naïve players dominate the industry and negatively impact elephant welfare. Machines are also beginning to replace work elephants in various parts of the country, doing away with the need to keep or preserve the species.

Despite all the threats to their survival, though, Shell suggests that elephants could carve out new niches for themselves. In an increasingly flood-prone world, for example, they could be redeployed from logging to disaster relief — as they were following the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. As Shell writes, “Until now, the Asian elephants’ principal working alliance has been with those who ride them in the forest. But this alliance could grow to include many other human beings as well.”

Now more than ever, he maintains, Asian elephants will face a more viable future if they find fresh ways to preserve their delicate connection with our species.

Rachel Love Nuwer is a freelance science journalist whose writing has appeared in The New York Times, National Geographic, Scientific American, BBC Future, and elsewhere. She is the author of “Poached: Inside the Dark World of Wildlife Trafficking.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

It really seems like this book misses more than it hits. Even though it’s too easy for Westerners to sit in judgement on the cultural traditions of “developing” countries, the ways elephants have been and STILL ARE being treated is a pretty easy case. Glossing over everything humans do to them in favor of lauding them for simply not exterminating the species is an extremely low bar for praise.

What we have done and allowed to happen to the Asian and African Elephant is the surest sign of our moral bankruptcy as a virtually worthless species.

Agreed, of all the species roaming earth we are the specious one.