Do Indoor Pools Really Need to Close for Lightning?

Across the country, pools close when lightning is in the area. For outdoor pools, the rationale is clear: About 10 to 15 people are killed by lightning in the United States each year, and the vast majority of fatalities and injuries occur outdoors, particularly around bodies of water.

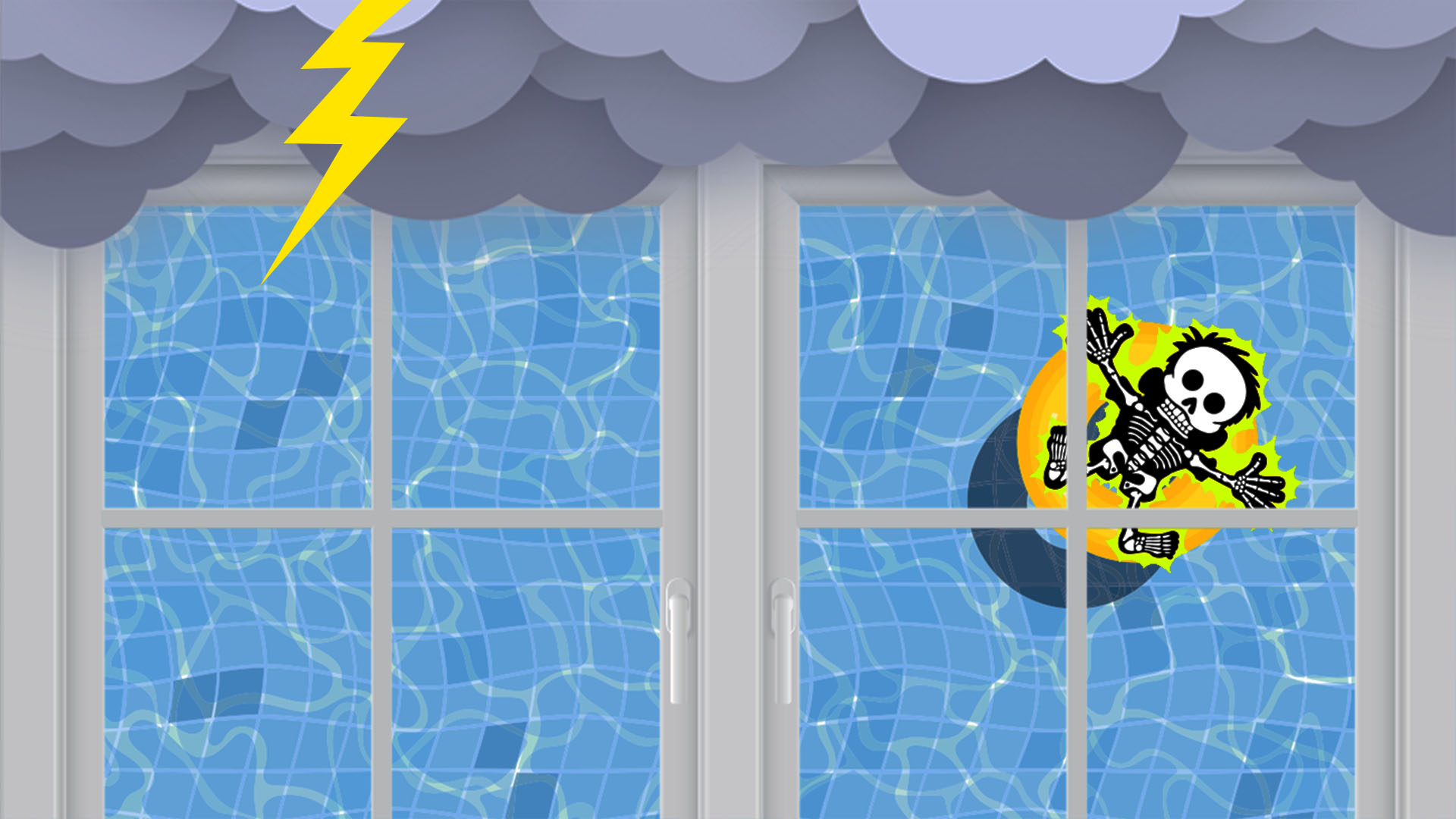

But should indoor pools close, too? Both the American Red Cross and the national YMCA organization say they should, over concerns that lightning’s electrical current could travel through a building and zap swimmers. Indoor pools across the U.S. are frequently shut down for weather, especially in summer, when lightning strikes increase.

Tom Griffiths, an expert in aquatic risk management, has spent years arguing that those pools — and organizations like the Red Cross — are getting things wrong. “We’ve created this monster, this fear of this risk that really doesn’t exist,” he said.

As far as Griffiths can tell, nobody has ever died or been hospitalized from lightning while swimming in an indoor pool. While it’s difficult to confirm this claim, other experts who spoke with Undark did not dispute it. “That’s probably true,” said Mitchell Guthrie, an electrical engineer who helps set global and national standards for lightning safety. Guthrie thinks it still makes sense to close indoor pools during storms: “I wouldn’t want to be the person that’s the first one on the list,” he said. In his view, exiting a pool is a minor inconvenience and a fair tradeoff for avoiding a major tragedy.

People are being asked to sacrifice worthwhile activities, said Griffiths, “because of a bogeyman that doesn’t exist.”

As it turns out, the question of how to handle such a remote but potentially dire threat has been the subject of longstanding debate within the world of U.S. aquatics. The conversation turns on questions of whether pools’ lightning protection systems are truly reliable, and whether the risk of swimming in an indoor pool exceeds the risk that a person might face upon exiting or being turned away.

This gives merit to the view that a well-maintained indoor pool can safely stay open in the presence of lightning, said Shawn DeRosa, director of the Bureau of Pool and Waterfront Safety for the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. Closure recommendations reflect the possibility of a catastrophic injury, but pool managers deal with such possibilities daily, he wrote in a 2019 article for Aquatics International magazine. Swimming pools, after all, carry an array of risks, including drowning, spinal cord injuries, and chemical leak exposures.

“A lot of things in life are possible,” said DeRosa, who also owns and operates an aquatic safety and risk management company. The question is, how probable are they, particularly when safety standards are in place?

By law, new and renovated buildings must be grounded, meaning they can dissipate electrical currents into the Earth. Lightning protection systems involve grounding, and more broadly the installation of lightning rods placed atop a building. If lightning strikes the rods, metal beams or wires direct the current down along the sides of the building and ultimately into the ground. This explains why a lightning-prone structure such as the Empire State Building can withstand dozens of strikes each year. It also helps explain why being inside during an electrical storm is so much safer than being outside.

Guthrie is wary of treating lightning protection as foolproof, however—and a direct strike isn’t the only possible route through which lightning can enter a building. The National Weather Service recommends avoiding all indoor plumbing, which would include swimming pools, when lightning is in the area, said Keith Sherburn, the NWS’s Severe Weather Program Coordinator. If lightning strikes a nearby tree or building, it could travel through the ground and potentially through a metal pipe that carries water into the building.

The number of documented fatalities inside a “substantial structure” is exceedingly low, noted Sherburn. Since 2006, there have been just two: One near a window, and the other involving a corded phone. But, he said, “we also don’t have official records of lightning injuries,” making it harder to know how often lightning injures people who are indoors.

The debate, perhaps, has less to do with the specifics of lightning science, and more with different approaches to risk. When it comes to water safety, Griffiths said, the goal is to balance risk while allowing people to enjoy their lives. One way to do this is to implement policies that consider both the frequency of an event and the severity of its outcome. Drowning deaths, for example, occur relatively rarely — about 4,000 times per year in the U.S. But because the outcome is severe, aquatics facilities implement extensive safeguards to reduce its likelihood.

Scenarios like lightning traveling through plumbing and into a pool may be possible in theory, but from a risk-management perspective, the low frequency matters, said Griffiths. And, in that broader risk-management view, kicking people out pools may bring its own set of risks.

“A lot of things in life are possible,” DeRosa told Undark. The question is, how probable are they, particularly when safety standards are in place?

In late 2018, DeRosa launched an online survey for aquatics professionals. He wanted to find out how indoor and outdoor facilities handled lightning storms. Representatives from nearly 250 facilities completed the survey, most from the U.S., Canada, and Australia. What they reported were a lot of inconsistencies.

Around 60 percent of the 174 indoor-pool operators indicated that they stay open. But of those that clear the water, more than 40 percent allowed patrons to use the showers and sinks, and only 13 percent advised staying indoors until the storm passes. For the sake of consistency, facilities that prohibit swimming during an electrical storm should also prohibit showering and handwashing, said DeRosa. They should also strongly encourage people to stay indoors. There are documented cases of people being struck by lightning in parking lots, he said, “so leaving the building may actually be more dangerous than staying inside the building.”

In general, there is just a lot of uncertainty around the risk of indoor swimming, said DeRosa. The presence of something like a glass wall, common in newly built pools, could shift the risk — not because of electrocution, but because lightning strikes can, in rare cases, shatter glass. In contrast, when he was head of aquatics for Penn State, the indoor pools at the school’s McCoy Natatorium lacked windows. On top of this, the state required regular electrical safety testing. Under those circumstances, he said, he felt comfortable allowing people to swim during storms.

Griffiths also stressed the importance of routine electrical inspections. Assuming a pool has gotten a nod from a licensed electrician, he said, it should stay open. “I feel horrible about this situation,” he said. He recalled a man in Texas who had once asked him to come and speak to the board of a hospital that operated a pool. The man used a wheelchair and depended on water exercise to keep him mobile. It took a lot of effort to get to the pool and navigate the ramps, and then as soon as he’d get wet, he’d have to get out because of lightning. People are being asked to sacrifice worthwhile activities, said Griffiths, “because of a boogeyman that doesn’t exist.”

Which isn’t to say it won’t ever exist.

“I am not aware of a single lightning researcher nor lightning safety organization who endorses staying in a pool in an electrical storm,” wrote Guthrie in a follow-up email. “(Those most aware of the potential threats suggest it is not a risk worth taking.)”

In Brooklyn MI 1977 my stepfather owned a house with a builtin indoor pool, that summer while in the pool a summer thunderstorm approached. My mother said that I ought to get out which I did, no sooner did I get out standing by the side dripping wet, when lightning struck in our backyard. The next thing I know is that I am picking myself up. My mother said a blue ball of lightning came in the pool room thru a screened window crossed the pool area and into the living room where she was sitting with my grandma. It then left thru another screened widow.