In Tennessee, an Experiment to Manage Behavior with an App

On a chilly morning in January 2020, Principal Stephen Byrd leaned towards the 9th grader sitting across the table in his office. Byrd asked the student, an African American teenager with a sparkly stud in one ear, what had happened. He’d just been sent to the principal’s office for having his phone out during class.

The student answered: “I don’t know” and “Yes, sir.” Soon he agreed to apologize to his teacher and keep his phone in his pocket once he returned to class. Byrd, a then 48-year-old White man with neatly trimmed brown hair and a touch of grey in his beard, gave the boy a lanyard so he could properly display his ID and sent him off to class with a smile, saying in his Tennessee drawl, “Get back to work.”

Until recently, such an interaction between the Ripley High School principal and a student who had broken a rule might have ended much differently. Byrd would have locked up the phone until the boy’s parents could pick it up and sent the student to an in-school suspension for at least the next class period. The teen would have missed instruction, possibly fallen behind in learning, and received a mark on his permanent school record. This scenario was once so common at Ripley High and Ripley Middle that in 2019, the state of Tennessee cited both as schools that disproportionately punish African American students and those with disabilities. The rebuke upset Byrd, who had graduated from Ripley himself and returned years later to coach its football team and teach social studies. This school was his family. His sons attended Ripley. If he wanted to prove that he and his majority-White staff weren’t perpetuating racist practices, he’d need to do something radically different.

Lauderdale County, where Ripley is located, is struggling with a chronic problem familiar to school districts across the country. Decades after researchers first called out a dramatic increase in the suspension and subsequent incarceration of children of color and those with disabilities, U.S. public schools have largely failed to reduce disproportionate punishment — or to disrupt the bias that behavioral science research suggests is deeply embedded both in people and systems. Despite improvements, nor have schools closed the gap in academic performance and graduation rates between Black and White children, which many policymakers consider impossible to eliminate as long as disproportionate punishment continues.

To help close that gap, educators in the district, including Byrd, placed their bets on BehaviorFlip, a technology startup that aims to track and catalog children’s behavioral health and development through a web-based program or smartphone app. The move is part of a nationwide proliferation of apps, platforms, and software for managing behavior and tracking academics and learning. “It’s grown exponentially in the last decade,” said Liz Kolb, a clinical associate professor in the School of Education at University of Michigan. “At this point we’re probably up to hundreds of thousands of education apps and tools that are being created and marketed to schools.”

BehaviorFlip’s founders say the tool supports the sustainability of restorative practices. With roots in the criminal justice system, restorative practices have been hailed for improving student behavior — at least for schools that commit to the lengthy training and implementation. Byrd and other educational leaders in the county hope the tool will bring teachers and students together, offer an opportunity to restore relationships, and support those children with the greatest need.

The county is a fitting test case for a discipline overhaul. With significant populations of White and Black students, its schools are also a microcosm of the stresses that face at-risk children on a national level: poverty, neglect, and complex mental and behavioral health challenges. Ripley households earn a median income of $34,813 and the poverty rate is 28 percent, according to the U.S. Census. (By comparison, the median income nationwide is nearly double that of Ripley’s, while the poverty rate is nearly a third.) Many children in the county have experienced trauma, parental incarceration, and parental issues with drugs or alcohol, making them statistically more likely to fall into the school-to-prison pipeline.

It makes sense for educators to grasp at promises of transformative results from technology companies. But actually distilling human behavior into a digital tool is far from simple — and no scientific studies or rigorous evaluations have proven that it works.

“Parents and educators are hungry for solutions, because children’s challenging behaviors have increased, especially with our most vulnerable children. The financial markets for behavioral technologies are very powerful,” said Mona Delahooke, a clinical psychologist based in Los Angeles, who studies child behavior and warns that apps can be counterproductive. “In my practice,” she added, “a lot of students whose teachers track behavior experience higher levels of anxiety.”

Ripley is a rural community in western Tennessee, full of lush green fields and trees, about an hour’s drive north of Memphis and about a 20 minute drive to the Mississippi River, where the state borders Arkansas. The streams in Lauderdale County have people fishing along the banks. Local pickup trucks are often outfitted with gun racks and hunting rifles. It’s hard to spend more than $20 per person on dinner at a restaurant.

Local points of interest include the Chickasaw National Wildlife Refuge to the west and the Alex Haley Museum to the south. Ripley is about 54 percent African American, 41 percent White, and 5 percent multiracial, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The district built Ripley High School, which was completed in 1969, to facilitate integration, because neither the local Black nor the White school was big enough to hold the combined high school population. But Ripley’s educational disparities continued, echoing national gaps.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the tough-on-crime movement prompted districts to adopt zero tolerance discipline policies across the U.S., causing suspensions and expulsions to skyrocket. By the end of the 20th century, civil rights advocates sounded the alarm about the gap in educational opportunity for Black and Brown students, in part due to disproportionate discipline. An influential 2011 report from The Council of States Governments and The Public Policy Research Institute at Texas A&M University, based on Texas school records, documented how suspensions hold students back academically and increase interventions by the juvenile justice system, putting children on the path to prison. The report also showed the disproportionate impact on African American students and those with disabilities.

In response to the alarms sounded by advocates, some large school districts banned discretionary suspensions for young children over the next few years — with Los Angeles Unified doing so for all students. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, under then-President Barack Obama, launched investigations. Those efforts helped nudge down overall suspension rates from a high in 2010, but the racial gap remained large. Researchers including attorney Daniel Losen at the UCLA Civil Rights Project documented that, in K-12 schools, Black students were suspended at four times the rate of their White peers, a disparity that’s doubled since the 1970s. And according to Losen’s research, Black students with disabilities face more than double the risk of suspension compared to their White peers with disabilities.

“A lot of people assume that most of these kids are violent or something,” Losen said. “No. In the states that have the data, it’s mostly minor misconduct that causes kids to be kicked out of school. And even for the arrests, it’s usually disruption of an assembly. It’s not because of a weapon or drugs, or they did something violent to someone.”

These discrepancies in student outcomes result from systemic racism and implicit bias, which is bias that rests beneath a person’s conscious awareness. (Other research has found similar issues in policing, employment, and health care.) In education, critics point to both systemically unfair policies and biased practices that disproportionately punish students of color. The intersection of poverty and race can exacerbate this inequity for students who are multiply marginalized. For example, a policy such as a school punishment for being tardy or out of uniform may land on Black students more frequently than their White peers if they have less access to transportation or lack the resources to buy clothes that meet school dress codes. Meanwhile, suspensions for insubordination rely on a teacher’s subjective judgment about disrespectful behavior. Recent studies suggest that preschool teachers spend more time watching Black children and rate their behavior to be more disruptive, as compared with White children — even when children’s actions are rated identical by objective measures.

Psychologists first described and identified implicit bias in the mid-90s, documenting how stereotypes about race, gender, or another identity group can cause negative outcomes for people in that group. This results from people in a position of power making snap judgments or decisions about which they’re unaware. For instance, police officers are more likely to use force on unarmed Black people than on people of other races and hiring managers are often more likely to select men over women.

Social psychology researchers have since launched study after study seeking to reduce and eliminate implicit bias. But most of the results were inconclusive, weak, or temporary, resulting in changes in bias for just a few hours or a few weeks. For example, researchers led by University of Wisconsin psychologists Patricia Devine and Patrick Forscher developed an educational program to reduce bias in study participants by treating it as a habit to be broken. The team published a paper in 2012 trumpeting the intervention as showing “dramatic reductions in implicit race bias.” In 2017, they followed up with an additional study with a larger sample size, making a more modest claim that the intervention produced “increased sensitivity to the biases of others and an increased tendency to label biases as wrong.” But by 2019, they published a meta-analysis of 492 research studies aimed at reducing biases, concluding that even when interventions can change someone’s result on a bias test, they generally showed “trivial changes in behavior.” The initial promise of their method fell flat.

“I’m skeptical that even if you were changing implicit bias, that that would be a useful thing to do,” Forscher said in an interview with Undark, noting that only about 7 percent of the studies the team included in the meta-analysis even attempted to measure change over time. “That’s utterly abysmal. If you want to use this research to understand practical outcomes, we’re not even in the same ballpark.” He added that it’s “even a bit irresponsible to use this research to speak to practical outcomes.”

The BehaviorFlip implementation relies on that research anyway, by training teachers on bias and referencing it during debriefs on the company’s app. And BehaviorFlip is far from alone: Despite the inconclusive evidence, organizations spend $8 billion a year on diversity training, often including an implicit bias session. Compared with interventions carried out as part of the carefully controlled research studies that end up in peer-reviewed journals, these trainings are typically run by facilitators with a range of qualifications, expertise, and skill. Sometimes a teacher will return from a conference where they received a crash course on the topic, and then present the material to colleagues without a deep understanding of the concepts or methods for changing bias. There is rarely an attempt to measure the impact of training on participants’ attitudes, much less to follow up with observations of behavior and outcomes.

To Russell Skiba, a psychology professor emeritus at Indiana University, a haphazard or incomplete bias training can be worse than nothing. “It’s really dangerous,” Skiba said, warning of backlash. “If you do any training like this poorly, people will feel like you’re blaming them, and they’ll get resentful about it.”

Indeed, a 2006 systematic analysis of research on diversity and anti-bias programs found that organizations were 7 percent less likely to promote Black women into management following diversity training. More recent research suggests that bias trainings have divergent impacts depending on how motivated people initially feel to fight prejudice.

Signs of the disconnect between research and practice appeared in Ripley after a one-hour session on implicit bias in the 2019-2020 school year, delivered by BehaviorFlip trainers to a packed room of teachers and administrators. After mulling over the training, Ripley Middle School Principal Cindy Anderson and then-Assistant Principal Matt Spraker, both of whom are White, expressed skepticism about some of the research findings they heard. For instance, the BehaviorFlip trainers cited a study, originally published as a working paper in 2007, that found evidence of NBA referees calling more fouls against players who were of a different race than themselves. That bothered Spraker, who officiates in basketball games.

“I thought about that several nights on the floor and I’m like, no, that’s not happening,” Spraker, who is now the assistant principal at Dyersburg Middle School, about a 30-minute drive north of Ripley, told Undark.

“The game moves too fast,” he added. (Based on researchers’ understanding of implicit bias, the speed of a game might actually make it harder to curb implicit bias, which is part of the body’s fast-processing system, or gut reaction. However, in 2014, in a follow-up study published as a working paper, the authors found the racial bias in foul calls had disappeared.)

Anderson and Spraker are typical of educators in a rural area like Ripley, with deep connections to the school and students. Anderson coached track and basketball and taught health, physical education, and social studies for more than two decades before becoming an administrator. Current parents at Ripley often include her former players, many of whom are African American, which helps her connect with their children. When she was coaching, she’d sometimes spot players acting up at practice or a summer camp and drive them home. In an interview in 2020, she and Spraker said they worried that they might be overcompensating by imposing harsher punishments on White students because they’re trying to correct the disproportionality against Black children. “It bothers me to think that I might do more to a White student,” she said. “Am I making an example there that I am being fair?”

Conversations like these — as well as educators’ general confusion about how to move from awareness to action against bias — convinced at least one leading scientist to change direction. From his origins as a researcher documenting bias and trying to change it, Forscher said he now believes that the focus should be on systemic racism. “I no longer think implicit bias is a useful lens for understanding race,” he wrote in a follow-up email to Undark. “In addition, many people who want to understand race in America take an individualistic approach, and implicit bias is a part of that. In reality, I think behavior change can happen with or without changing implicit bias.”

Forscher said he’s “come to think that many organizations want to use implicit bias training as a PR move, a way to redirect blame on employees.”

BehaviorFlip came to Ripley in 2019 after then-Assistant Superintendent Sherrie Sweat read the book “Hacking School Discipline,” by two of the program’s founders, Nathan Maynard and Brad Weinstein, and sought their help in changing the district’s approach to discipline. The book grew out of a professional collaboration between Maynard and Weinstein, who met at Purdue Polytechnic High School, where Maynard was dean of culture and Weinstein was director of curriculum and learning. That working relationship led them to launch BehaviorFlip, along with a third colleague, Jason Lewicki, a software engineer. The program currently operates in 42 schools in 26 districts — totaling more than 15,000 students.

BehaviorFlip relies heavily on restorative practices, a framework rooted in criminal justice reform. Restorative practices mark a departure from the top-down system teachers are accustomed to, which prescribes clear punishments for student infractions. Rather than identifying who broke a rule and what punishment they deserved, educators would ask: What is the harm? And who was harmed? By including the opportunity to repair harm, BehaviorFlip aimed to facilitate a key tenet of restorative practices: restoring relationships after a fracture. Educators could assess what needs and obligations arose and how the harm could be repaired. The process of talking through this with students leads them to restore the relationship among all parties by finding a way to make amends to the person or people who were affected.

The BehaviorFlip program functions as a digital behavior log. From the home screen, administrators have several options: Reviewing behavior records for an individual student, an entire class, or specific educators. Everyone from the principal to a cafeteria aide could mark conflicts or problem behavior in the program, using a drop-down menu with optional comments, and also note whether educators had resolved the issue and strengthened the relationship with students. By looking for patterns in the data, administrators could identify struggling students and educators alike, for follow-up coaching and support. They could set alerts to be notified of interventions or early warning signs of problems.

But some experts are wary about the approach. Ross Greene, a psychologist and founding director of Lives in the Balance, a nonprofit that provides resources, training, and advocacy to support children’s behavioral health, said a program that tracks behavior focuses attention on the wrong area. Instead, he argues, educators should try to identify the problems that are causing inappropriate behavior and solve those issues. For example, if a student often struggles with math and runs out of the room or has an outburst during that class, simply asking them to restore the relationship won’t solve the math problem.

“The problem that’s causing that behavior is difficulty completing that particular task in math, and that’s what we should be focused on,” Greene said, while noting he hadn’t evaluated BehaviorFlip.

“I wouldn’t be that enthusiastic if the primary focal point of the app is to just give us another way to more efficiently count behaviors,” he added.

(To move away from connotations around discipline and misbehavior, Maynard recently told Undark, BehaviorFlip is undergoing a rebrand. The program will soon be renamed HiveFive, he said, representing “our five pillars and focusing on our proactive support.”)

Like many apps used in schools across the country, BehaviorFlip’s efficacy has not been evaluated in any controlled or systematic studies. (Given the expense and time of conducting such evaluations, it’s common for educators to adopt apps or educational practices without rigorous study.) Instead, according to Maynard, BehaviorFlip relies on research about restorative justice and trauma-informed educational practices: case studies of restorative justice in education, which describe self-reported success, as well as a randomized controlled evaluation of a widely adopted model that has found improved school climate, an overall drop in suspensions, and reduced disparities in suspension for Black and low-income students.

The Ripley schools provided a road test of the effectiveness of BehaviorFlip in practice. At a meeting in January 2020 to review the app’s rollout, binders formed piles in the center of a conference table. Administrators pored over discipline data. BehaviorFlip co-founders Maynard and Weinstein sat alongside principals Anderson, Byrd, and members of their leadership team. Their primary goal: to assess whether the district was making progress in reducing the disparity between suspensions and expulsions of African American and disabled students.

Assistant Superintendent Sweat, who has since retired, urged the administrators to rely more heavily on a new process Maynard and Weinstein suggested for discipline, termed the Zone. In the Zone, an assigned staff member works with children on their anger management and other social and emotional skills. The educator might assign a reflection, such as what makes someone angry, as opposed to old-school practices like standing students against the wall in shame or sending them home early. Most important for the administrators in the room, the Zone represented an interim step that stopped short of a permanent data point against either the child or the school: It wouldn’t automatically count as an in-school suspension, a mark that would follow the child throughout their educational career.

Next, Sweat told the administrators to go through the first semester’s data line by line, to see whether they had given both in-school and out-of-school suspensions to the same child for the same offense, or recorded multiple suspensions for the same incident, effectively double or triple counting.

“It could be that we’re going in there recording three different offenses for basically the same action, and we’ve talked about that,” she said, gazing through clear-rimmed glasses at the assembled educators. “So I want you all to do that and see — you’re going to be shocked at how much you can bring these numbers down.”

Cleaning the data this way may not have been what Tennessee had in mind when the state censured the Ripley schools, but Sweat said that for her team, it was an important part of the solution. U.S. public schools are awash in data, from attendance, assessments, reading levels, math mastery, grades, and test scores to discipline referrals and tardy marks. Ripley teachers would be recording even more data under the BehaviorFlip system as they tracked students’ behavior and noted teachers’ responses — or lack thereof.

To Delahooke, the clinical psychologist in Los Angeles, tracking and rewarding behavior, no matter the good intentions, can actually amp up anxiety for some children, rather than helping them learn to self-regulate. “When students see themselves being tracked like that, they’re going to feel worse about themselves, not better,” she said. “Using a tracking system is the new language placed on top of the old model.”

Weinstein and Maynard acknowledge that technologies like BehaviorFlip could potentially be weaponized against students in a punitive way. The training that goes along with the program and the focus on restoring relationship serve as counterbalances, Maynard said. Schools rely on data to understand how students are doing and which teachers need to be coached, he told Undark.

In order to keep the focus on relationships in the January meeting, Weinstein encouraged the Ripley educators to log positive notes whenever possible, under the app’s category of resiliency, based on research showing that the higher the ratio of positive to negative interactions with a student, the stronger the relationship and also the student’s academic success. Aside from instruction, about 80 percent of teacher time should be spent developing relationships and building community, such as through classroom meetings and individual conversations with students, Weinstein said, versus 20 percent managing conflict, repairing harm, and restoring relationships. He cited an idea from parent educator Pam Leo in stating that teachers can either meet students’ emotional needs upfront, or spend even more time dealing with negative behaviors caused by those unmet needs.

“It cannot be punitive in its purpose,” Sweat reminded her colleagues. Rather, she said, Behavior Flip needed to be restorative.

“And let’s just be honest,” she later added, “when you look at the data from last semester, teachers did very little restoring.”

The new restorative practices framework required more creativity, judgment, and digging into the messiness of students’ emotions to understand the root causes of misbehavior. It also, above all, required a focus on establishing, feeding, and repairing relationships.

“That’s where they’re having trouble. Y’all, I could see it written all over their faces today. They’re having trouble knowing how to restore, repair the harm, right there on the spot as it’s happening,” Sweat said, acknowledging the challenge in adopting the new approach. What “I know because I’ve done it from experience and I’ve had to change my ways a lot,” she continued, “is that it’s not a battle of wills and it’s not who’s going to win. It’s a whole culture shift. It’s a whole mindset in how you perceive that child.”

Later that week, on the first day back after winter break, teachers across Ripley Middle School were trying to model the new approach by helping students adjust from whatever experience they’d had over the holidays. In her classroom, English teacher Alisha Milam stood at the front of the room, explaining that the class would be sharing experiences from the break. She asked about the number of days in a row they had worn the same outfit, turning from child to child to get their answers. Students shifted their bodies to look at the person who was speaking. The conversation prompt was the same Milam and her colleagues had experienced in BehaviorFlip teacher training just a couple of days earlier. The exercise was a restorative circle — a central tool of restorative practices aimed at building community, relationships, and trust.

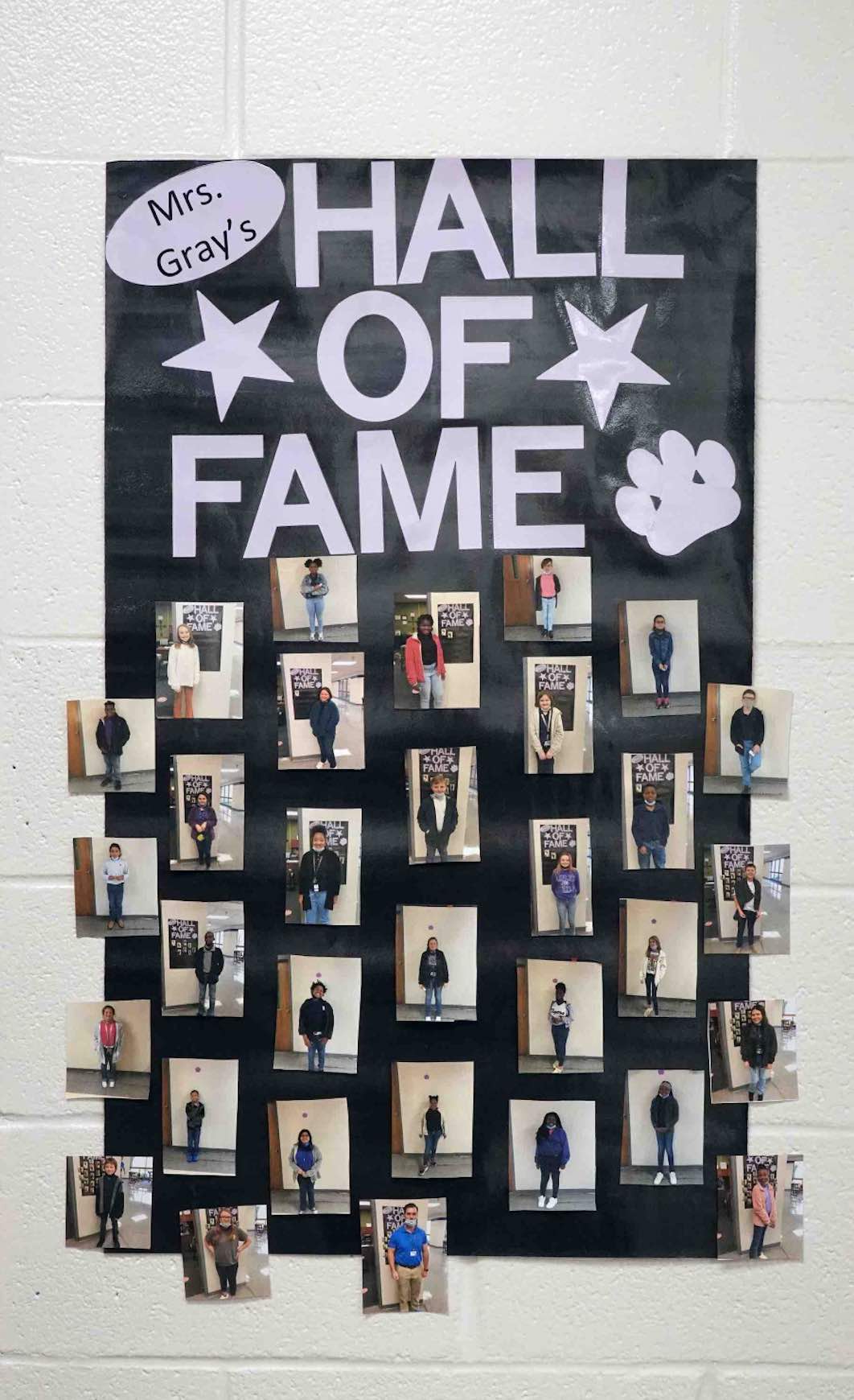

One teacher uses a hall of fame to draw attention to students with good behavior at Ripley Middle School.

“I had a kid in my first class that said he wore an outfit for 12 days,” Milam, who is White, told her students with a chuckle, while noting the child did shower. “He didn’t go outside and he never did anything but watch TV and play video games. So he just wore the same pajamas.”

Students volunteered their answers: Two days. Three days. Four days. One day. Finally, a girl topped the classroom by saying she wore the same clothes for a whole week straight. During the circle, other personal tidbits came out. One student was at his family’s lake house. A girl visited cousins and aunts. Another student announced that their uncle drew their name in a gift exchange but forgot to buy a gift. This sort of classroom sharing may seem trivial, but it can form the basis for trusting relationships and helps kids feel safe in the class community — especially those with trauma histories and a lower threshold for being reactive or defiant. “Those classroom meetings can be really a powerful way to regulate nervous systems, which is the groundwork for eliminating those big challenging behaviors,” said Delahooke. “The teacher is actually embodying the social engagement system, embodying responsive care and attunement with the classroom and is generally connecting.”

Next, Milam started a slideshow about classroom expectations. “All right, guys, what are the first three words in my very first expectation?” she asked, calling on a student who raised his hand.

“Respect, respect, respect,” he responded.

“You know from the time I showed you this in August. I’ve been faithful to this all year,” said Milam, who was in her second year at Ripley Middle. (She has since left the school and now works as an assistant clinical professor at Mississippi State University – Meridian.) “This is the foundation of our classroom, is a mutual respect from you to me as your teacher and facilitator, and from me to you as an individual.”

Milam shared a slide of rewards for desired behavior and apologized for not following through and giving the rewards in the fall. “We go through that PowerPoint to hold us all accountable. It reminds you of how you’re expected to act in the classroom and our procedures for turning in papers and late work and all those things,” she said. “But it also helps you hold me accountable for our reward system because good behavior deserves to be rewarded.”

Later that day, in a classroom down the hall, eighth grade math teacher Tonia Estes, an African American woman, introduced BehaviorFlip and the concept of repairing harm. She gave the example of a girl who forgot to bring in her school ID. “Then I would write her up in BehaviorFlip because she doesn’t have her ID,” Estes said. However, every student has the chance to remove the negative points. “This will take one to two to three minutes for the student and teacher to talk about what happened, what effect it had, and the student is going to determine how to repair the harm,” she said, reassuring them that the new year meant a clean slate.

But in other classrooms at Ripley High and Middle Schools, teachers displayed uneven approaches to adopting BehaviorFlip and restorative practices. Some teachers lectured students at length, despite Sweat’s admonition not to preach at them. Others used BehaviorFlip as a light threat to keep kids in line, saying things like: “If you do that tomorrow, I’m going to have to put you in BehaviorFlip.”

Byrd estimated about half of the teachers were skilled in relationship building and the rest needed coaching. The school system seemed on the right track, with administrators committed to change. They’d invested in two full days of training that explained the school-to-prison pipeline and urged educators to view the goal of discipline as teaching skills, not enforcing order or rules. Some teachers already had begun adopting the recommendations.

Students seemed comfortable in the building and displayed strong relationships with educators. Middle school students, unprompted, refastened a sign that had come down from the wall. In one classroom, the teacher had adopted unconventional seating, including lawn chairs, Adirondack chairs, and stools with high tops, almost like a coffee shop.

The stage seemed to be set to complete the transformation of the schools in both teaching practices and the underlying technology.

Then, Covid-19 came.

Just as it happened for students across the world, the pandemic drastically changed school in Lauderdale County. To guard against Covid spread, the district assigned half the students to attend on odd days and half on even days in the 2020-21 school year. Instead of 800 teenagers crowding the halls and classrooms of Ripley High School, only about 300 showed up each school day. About 100 initially chose virtual school, but some of them failed to return when in-person school became the only choice. The middle school saw about a third of students start out virtually, Anderson said. Fewer students in classrooms and halls meant fewer chances for unwanted behavior, and so administrators and teachers had to change their approach with BehaviorFlip.

The results were patchy. At Ripley High School, Byrd said the administration and teachers primarily used BehaviorFlip for tardies. Behavior problems dropped dramatically because there just weren’t as many students in the building. Teachers could connect more effectively when they had only 10 or 12 students in a class, instead of 25. One teacher named Danita Esdale — who’d sent the young man to Byrd’s office in 2020 for having his phone out — said she’d had so few problems with discipline that she didn’t even find it necessary to track issues with the app. The prior year, the program had helped identify patterns, such as one group of students who behaved fine in their first class but acted out in their fifth class. But in the 2020-21 school year, the educators were focused on following pandemic protocols and ensuring that all students received Chromebooks for remote instruction. The school started an advisory program to encourage relationship building and make sure one adult knew every child on a personal level — their interests, concerns, and pressure points. Notably, the political climate had changed, with the Tennessee legislature banning the teaching of critical race theory in public school in spring 2021, which would take effect that fall. That wouldn’t impact BehaviorFlip, but it signaled a shift in attention. Local educators could be forgiven for receiving a muddy message about racial justice as a priority, where previously the signal was clear.

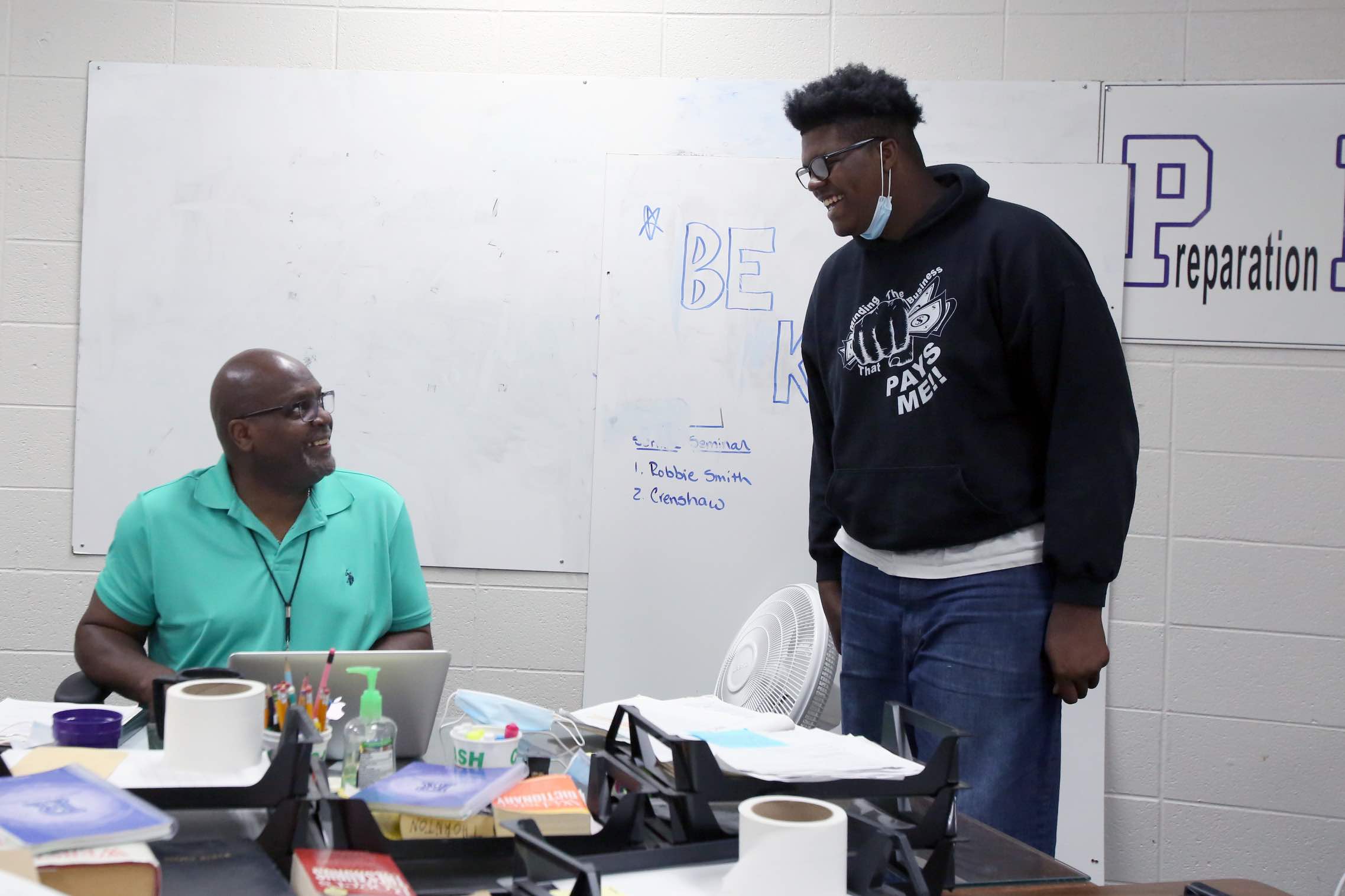

Byrd effectively turned the in-school suspension room into a technology and extra support resource. He reassigned the educational assistant in charge of in-school suspension, Wilton Jones, to manage Chromebooks and motivate lagging students to catch up on their work.

Educators dropped plans for using BehaviorFlip to track restorative circles and give positive reinforcement. Instead, Jones, an African American man, relied on decades of experience building relationships through volunteer work at the Boys and Girls Club and the schools his children and stepchildren attended in Milwaukee. “I listen a lot,” he said. “I do the two L’s. I listen; then I lecture.”

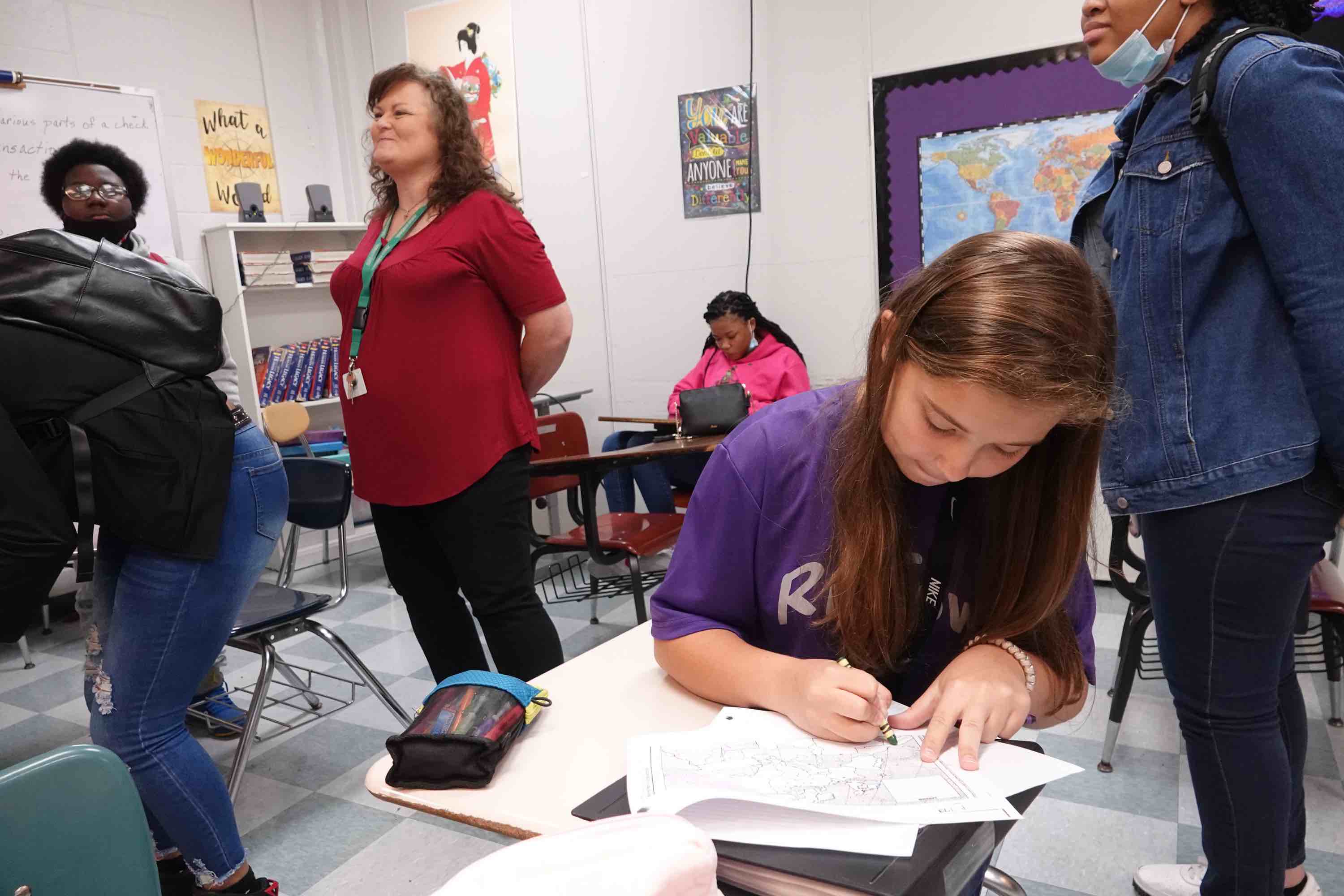

In one ninth-grade history class, teacher Robbie Smith, a White woman, was preparing the students for an upcoming test by reviewing the causes of World War I, the allegiances of various countries, and the key figures. She assigned an extra credit map project with about eight minutes before the bell. Some students began working on the map while others packed up their belongings. A few clustered around Smith, who asked what they thought about BehaviorFlip.

“It doesn’t do anything really,” said Sydney Parmenter, a White girl. “You get like 8,000 warnings and they don’t ever do nothing.”

When asked what makes the difference in motivating students to behave as they should, Sydney said it depends on the teacher.

“On the teacher,” a White boy agreed, before adding another thought: “On me.”

“It depends on the student,” said Damya Taylor, an African American girl. “Some of the students want to cause fights and some don’t. Some don’t like each other.”

No mention of positive marks in BehaviorFlip, restorative circles, or repairing the harm. Those phrases drew blank looks. The technology seemed to have replaced the prior, punitive system without much difference in impact, from the students’ perspective.

But at Ripley Middle School, Anderson and Spraker continued the BehaviorFlip implementation despite the pandemic. They and the teachers had ramped up use of resiliency, the BehaviorFlip term for desired behavior, letting kids earn rewards such as a dress code pass, snacks, or being featured on the school Facebook page. To stay connected to all students during the pandemic, Anderson and then-Assistant Principal James Barbee drove to the homes of remote students who hadn’t picked up progress reports. One house had such a rotted-out front porch that Anderson told Barbee to stand on different boards than her, so they didn’t break through. “Our teachers need desperately to do this,” Anderson said, “so they can see exactly where the students are coming from.”

Like the high school, Ripley Middle School saw discipline referrals drop dramatically. The school had 600-plus annual office referrals before they started the push to reform discipline, Spraker said. During the 2019-2020 school year, when BehaviorFlip was first implemented, referrals were down in the low 100s, before Covid shut everything down. In the first full pandemic year, referrals were at 89 in late May. But of those 89, 70 were for African American students, so the gap was still highly disproportionate, Anderson said, although some of the data still reflected counting the same student multiple times for the same incident.

Lauderdale administrators, as with dozens of U.S. school district leaders interviewed during the pandemic, expected to draw few useful conclusions from the discipline data gathered in recent school years. In spring 2020, the quick pivot to virtual learning left educators scrambling just to get students online, much less assess their learning, administer standardized tests, survey them on school culture, or keep up on behavior data. Even before the pandemic, record-keeping and reporting varied widely by district. By law, school districts are supposed to report all discipline and arrest data to the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights. But UCLA’s Center for Civil Rights Remedies found that more than 60 percent of districts reported zero arrests related to school — an implausible number given the known annual arrests at high schools in large districts such as Los Angeles or New York City. “We know that that’s not accurate,” UCLA’s Losen said.

|

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

In the Ripley schools, the pandemic causing a gap in comparable behavior data sent to the state and federal government could be the breathing room educators seek to give restorative practices a chance to take hold. BehaviorFlip offered educators a middle option to track inappropriate behavior without having to put a demerit on students’ official record. BehaviorFlip points could be wiped clean if the child repaired the harm. Both the student and the school leadership benefitted from that buffer. Administrators pushed teachers to have conversations with students and investigate the cause of bad behavior, rather than immediately jumping to an office referral.

BehaviorFlip served a purpose for Estes, the eighth-grade math teacher. It reflected an upgrade from the prior paper system, but ultimately merely reinforced the importance of relationship building. “Just like a stove can cook your food for you, but it can’t make it good,” she said. “You have a stove, it’s got the bells and the buttons and the conveniences and all the right parts and tools, but unless you know how to love and prepare a good meal, it won’t matter anyway.”

Byrd and other educators across Lauderdale County seemed to have to learned that the messy problem of student behavior and racial bias could not be solved with data and technology alone. But they’re determined to keep trying, many told Undark, and have committed to keep using BehaviorFlip alongside relationship building and other strategies.

The BehaviorFlip founders emphasized in their training that the real work lay in educator mindsets and practices, rather than the app interface or the points being racked up. The technology is just a tool, which can be used as part of a faithful implementation of restorative practices — or turned into another means of punishment, like the old ways, they said. Educators would need to continually tune into students, investigate the causes of their behaviors, and support them in repairing harms.

Used as directed, Maynard said, apps like BehaviorFlip can help by nudging educators to stop and listen to the student’s perspective on an issue. Like Estes, Milam used the program faithfully, and appreciated the alerts that reminded her to work with a student to repair the harm. Just that week in May of last year, a student coming in late had mouthed off; it was unlike him, as he had never been disrespectful previously. She was too busy to address it in the moment, but later she sat down to talk with him. It turned out that his mother’s car had broken down — and had been breaking down recently — and he was worried. “Time and again, there’s always something foundational, when kids are reacting that way,” she said. “So that’s exactly what it was. And I was like, wow, you know, I’m so glad that this didn’t escalate. Because in the past, I’ve seen that happen.”

Ultimately, psychologists and school administrators emphasized, the way the technology is used comes down to the teachers and their skill in relating to children. In the high school cafeteria, an African American girl with long, purple-streaked hair, agreed with the other students that the marks in BehaviorFlip didn’t stop disruptive behavior.

“From what I’ve seen, when kids are acting out, most of the time it’s something personal or something happening at home,” she said. “Just talk to them, ask them. Because nine times out of 10, they’ll tell you.”

This article was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University.

Katherine Reynolds Lewis is an award-winning journalist covering children, race, gender, disability, mental health, social justice, and science.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

You guys really do an excellent job on these in-depth investigations.