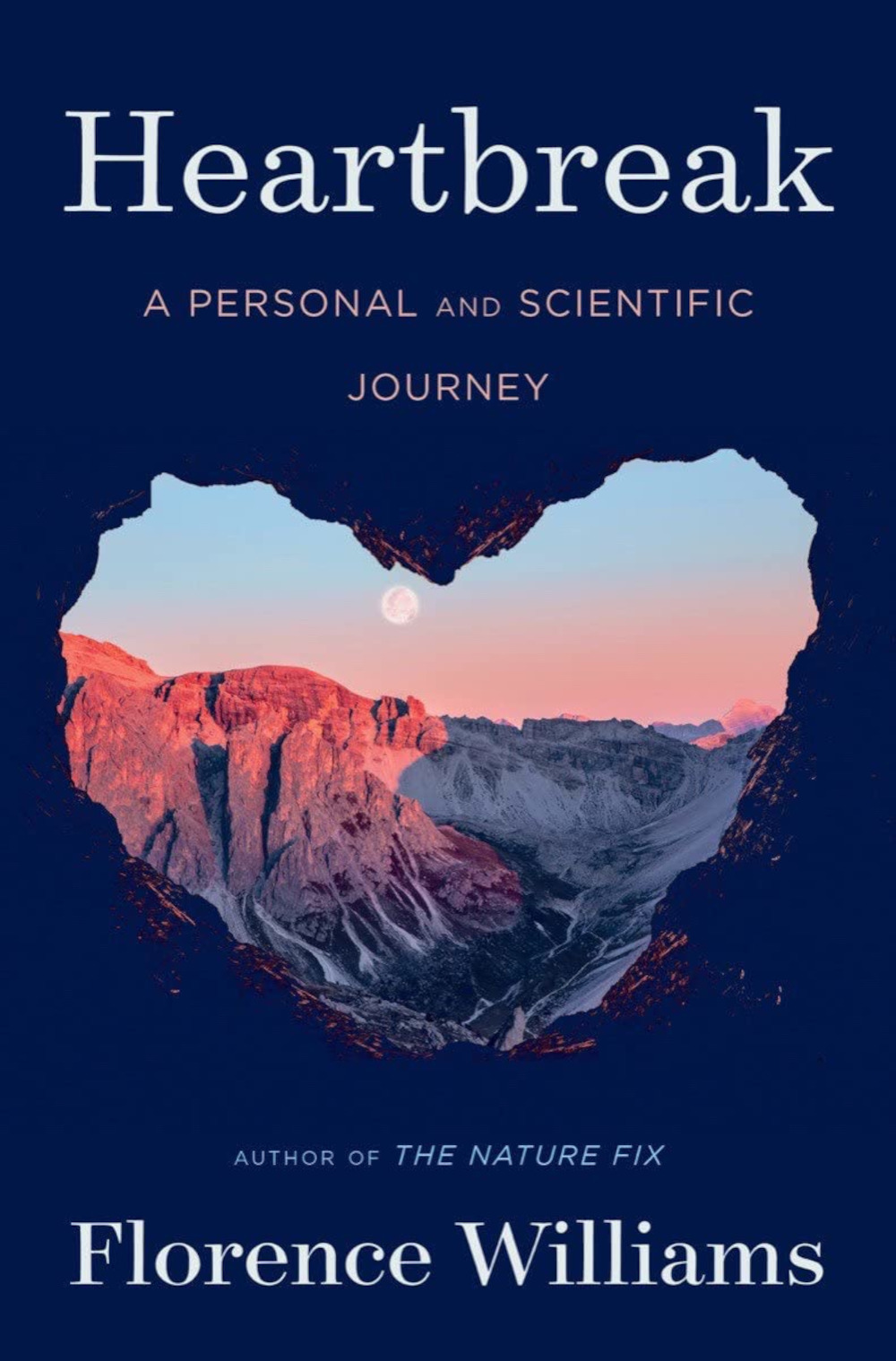

Early on in “Heartbreak: A Personal and Scientific Journey,” science journalist Florence Williams notes that “much has been written about the science of falling in love, but very little about what happens on the other side. Only in recent years has science begun to excavate some of the literal biological pathways of this brand of pain.”

For starters, there is an actual medical condition called “broken-heart syndrome,” clinically known as takotsubo cardiomyopathy, which is a weakening of the heart muscle following a sudden shock to the system.

BOOK REVIEW — “Heartbreak: A Personal and Scientific Journey,” by Florence Williams (W. W. Norton & Company, 304 pages).

This is just one of the many effects heartbreak and trauma can have on the body, Williams writes. Heartache also weakens the immune system, we learn, and brains light up in a scanner in a manner similar to when we experience intense physical pain. It can also lead to physical illnesses, and language and cognition can be affected. “Heartbreak is one of the hidden land mines of human existence,” one genomics researcher tells her.

Williams, the author of “Breasts: A Natural and Unnatural History” and “The Nature Fix,” had a deeply personal motivation for exploring this terrain. After her husband told her he needed to leave their 25-year marriage, she couldn’t sleep, she lost 20 pounds, couldn’t think straight, and eventually became at risk for diabetes. She also became fascinated with how loneliness and heartbreak transform the body, who is at risk for the most detrimental changes, and how this damage might be ameliorated.

So she set out to interview researchers and therapists in a wide range of fields, essentially using herself as an experiment: She wanted to see what was going on with her cells, her neurons, and her sense of self. She traveled to labs around the world to explore the latest biological findings about the mind-body connection and the psychological impact of rejection, monitored her own blood work, and participated in neurological experiments to measure the beneficial effects of social support.

She also attended an EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) workshop for divorced people and had a session with a therapist who works with MDMA (ecstasy). She took the MDMA because she had read about the potential clinical benefits of microdosing with another psychedelic compound, ketamine, and about how some trauma therapists and couples counselors were using MDMA to help make painful events more bearable.

The therapist (whose credentials are never given) gives her not only MDMA but also psilocybin. At one point, the therapist notes that she probably should have given Williams two smaller doses of MDMA instead of one large dose. “My ecstasy hangover lasted for days,” Williams writes. “I looked up my symptoms, and was not pleased to learn that at least one scientist believes that even one hit of MDMA can permanently damage serotonin pathways in the brain.” (Her surprise at this is notable, given her extensive research into the other medical treatments she pursued.)

Throughout her journey, Williams manages to retain her sense of humor, and her writing is honest, even when ruminating in detail about her divorce. At times her self-awareness borders on self-absorption, but her storytelling opens up when she interacts with researchers and therapists, and when describing her experiences in nature and with therapeutic groups and organizations designed for trauma survivors.

She seems particularly comfortable when exploring the healing benefits of being in the wilderness. In fact, the overarching theme seems to be that the more you feel a part of something larger than yourself, the more likely you are to heal. Researchers have found that the sense of wonder one feels when looking at a painting or coming across something in nature stimulates the connection between areas of the frontal cortex associated with self-concept and areas of the brain that have to do with processing sensory and motor information. Brains that have multiple connections like this, Williams writes, are better able to make sense of upsetting or confusing events.

“If you’re connected to art, nature, and beauty, you are periodically being forced out of yourself to think about connectedness to something bigger than you,” a psychology professor tells her. “And if you can do that, then learning is better and understanding is better.” In other words, Williams writes, a sense of awe can help the heartbroken feel less alone and more purposeful.

To investigate the benefits of nature and physical activity on trauma victims, Williams joins a backpacking trip with sex-trafficking survivors in Colorado. “Heartbreak is trauma,” Chelsea Van Essen, a trauma therapist who was the guide on that trip, tells her. “Absolutely. It’s trauma because it affects you on so many levels. It dismantles your identity.”

Traumatized brains are different: The amygdala has heightened reactivity, which changes how threats are read, and less activation in the insula, which sends signals to and from our organs and muscles. Physical activity, especially in nature, can help to rewire traumatized brains, Williams writes, potentially jumpstarting the circuits between bodily sensations and the brain: “If you’re busy feeling what is happening right now, it’s harder to continue feeling the traumatic events of the past.”

Neuroscientist Shane O’Mara at Trinity College Dublin later echoed this intuitive idea, noting that movement can help prevent depression and various physical ailments. “As blood pumps and new neuronal growth factors flow, we become more creative, more self-aware, more ourselves,” Williams summarizes from O’Mara’s book, “In Praise of Walking.”

In the end, of course, no scientist or treatment can offer a single cure for the pain of heartbreak. As Williams discovers at the end of her long post-divorce odyssey, “the best heartbreak cure of all” is simply time.

“The literature predicts it takes three to four years for one’s emotional and physical health to return to baseline, at least after a long marriage,” she concludes. “I didn’t have pre-breakup blood to compare, but at two years out from our split, my biomarkers were getting sparkly and at three years out, I know I am feeling like a fuller, keener, softer, wiser version of myself than ever before.”

Jaime Herndon is a medical and parenting writer who also writes about popular culture in her spare time. Her work has appeared in New York Family, Book Riot, Fiction Advocate, Today’s Parent, Motherly, Healthline, and Health Union, among other publications.