Government’s Use of Algorithm Serves Up False Fraud Charges

I n 2014, Carmelita Colvin was living just north of Detroit and taking classes at a local college, when she received a letter from the Michigan Unemployment Insurance Agency. The letter stated that she’d committed unemployment fraud and that she owed over $13,000 in repayment of benefits and fines.

Colvin’s reaction, she recalled, was: “This has got to be impossible. I just don’t believe it.” She’d collected unemployment benefits in 2013 after the cleaning company she worked for let her go, but she’d been eligible. She couldn’t figure out why she was being charged with fraud.

What Colvin didn’t realize at the time was that thousands of others across the state were experiencing the same thing. The agency had introduced a new computer program — the Michigan Integrated Data Automated System, or MiDAS — to not only detect fraud, but to automatically charge people with misrepresentation and demand repayment. While the agency still hasn’t publicly released details about the algorithm, class actions lawsuits allege that the system searched unemployment datasets and used flawed assumptions to flag people for fraud, such as deferring to an employer who said an employee had quit — and was thus ineligible for benefits — when they were really laid off.

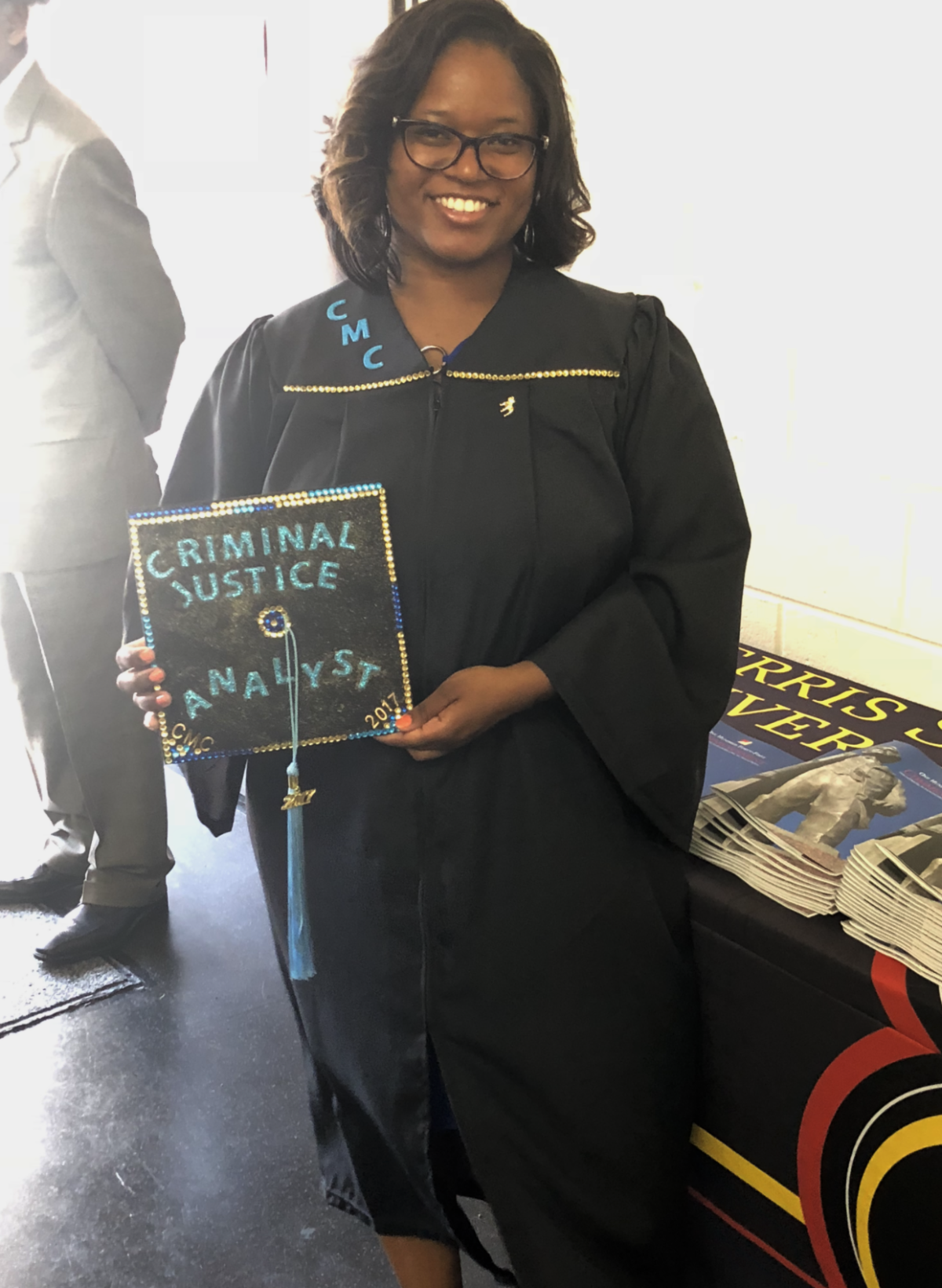

Carmelita Colvin, who obtained two degrees in criminal justice, only to be denied a job with a county sheriff’s office because of an erroneous fraud charge and her then outstanding debt to the state.

Visual: Courtesy of Carmelita Colvin

Over a two-year period, the agency charged more than 40,000 people, billing them about five times the original benefits, which included repayment and fines of 400 percent plus interest. Amid later outcry, the agency later ran a partial audit and admitted that 93 percent of the changes had been erroneous — yet the agency had already taken millions from people and failed to repay them for years. So far, the agency has made no public statements explaining what, exactly, went wrong. (Lynda Robinson, an agency representative, declined Undark’s interview request by email, writing: “We cannot comment due to pending litigation.”)

Government use of automated systems is on the rise in many domains, from criminal justice and health care to teacher evaluation to job recruitment. But the people who use the algorithms don’t always understand how they work, and the functions are even murkier to the public.

“These types of tools can be used to inform human judgment, but they should never be replacing human beings,” said Frank Pasquale, a professor of law at the University of Maryland who studies accountability in the use of these opaque algorithms. One of the big dangers, he said, is that the systems fail to give people due process rights. If an algorithm is “used by the government, there should be full transparency,” he added — both in how the software works and the data it uses — “to the people who are affected, at the very least.”

In cases like Michigan’s, flawed automated systems punish people whom the agencies are supposed to help, said Michele Gilman, a University of Baltimore law professor who directs a legal clinic that represents clients with public benefits cases. She pointed to other examples, including algorithms adopted in states like Arkansas and Idaho that agencies used to cut Medicaid benefits, sometimes erroneously. And the issues extend beyond the United States: In 2019, a Dutch court found that an algorithm used to detect welfare fraud violated human rights and ordered the government to stop using it.

In Michigan, while the agency says it repaid $21 million, attorneys in the class-action lawsuits argue that this doesn’t account for all of the damages. People like Colvin suffered long-term harm — many came out with damaged credit and lost job opportunities and homes. More than a thousand filed for bankruptcy.

Nearly half the states in the U.S. have modernized the software and information technology infrastructure for their unemployment insurance systems. In many cases, these updates are crucial to keep the systems running smoothly and many actually help claimants more easily file for benefits. But this is not always the case — in Florida, for example, the new system adopted about five years ago made it much harder for people to apply. Gilman and other researchers that Undark spoke with are also concerned that in the coming years, states may adopt algorithms that lead to similar problems as in Michigan — particularly if they cut human review of fraud charges, in violation of federal due process requirements. With an unprecedented surge in unemployment claims during the Covid-19 pandemic — more than 40 million Americans have filed since mid-March — the problems could be amplified.

The automated system in Michigan is “a case study in all the ways an algorithm can go wrong,” Gilman added. “The citizens shouldn’t be the guinea pigs in testing whether the systems work.”

Michigan’s automated system popped up just after the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, when the auto and other manufacturing industries were hit hard and workers applied for unemployment benefits at high rates. Such benefits are intended to help those who have lost a job through no fault of their own, and are funded by federal and state payroll taxes. Benefits typically last 26 weeks, though the federal government covers extended benefits during economic downturns, including today’s Covid-19 crisis.

In March 2011, Rick Snyder, the newly elected Republican governor of Michigan, signed a bill shortening state unemployment benefits from 26 to 20 weeks. The bill also allocated funding for software to detect unemployment fraud.

The state’s unemployment agency hired three private companies to develop MiDAS, as well as additional software. The new system was intended to replace one that was 30 years old and to consolidate data and functions that were previously spread over several platforms, according to the agency’s 2013 self-nomination for an award with the National Association of State Chief Information Officers. The contract to build the system was for more than $47 million.

At the same time as the update, the agency also laid off hundreds of employees who had previously investigated fraud claims.

While MiDAS’s exact process isn’t public, interviews with attorneys and court documents from class action lawsuits provide some context. Part of the system searched records of employers and claimants in its database, then flagged people for potential unemployment fraud. Next, MiDAS sent questionnaires to an electronic mailbox on the benefits website that recipients may not have had reason to monitor, gave them 10 days to respond, and then sent a letter informing them they had been charged with fraud. After a 30-day appeal period, the system began garnishing wages and tax refunds. The agency later acknowledged that in the majority of the cases between 2013 and 2015, the system ran from start to finish without any human review.

Using automated decision-making systems to detect fraud is a problem because the stakes are so high, said Julia Simon-Mishel, an attorney at Philadelphia Legal Assistance who has served on the advisory committee for Pennsylvania’s unemployment compensation benefit modernization for the past two years. The automated systems don’t always gather key information or allow for “a back and forth that is required by federal guidelines, in terms of the conversations that states need to have with an employer and a worker,” she said.

“If you’re just using analytics to automatically flag fraud without anything else, you have a garbage in, garbage out problem,” she added. “Who knows whether the data you’re using to build your predictive analytics is correct?”

Some of the bad data comes from simple, unintentional application errors. Public benefit applications are often complicated, said Gilman, who called them “the tax code for poor people.” Because of this complexity, the majority of overpayments are due to either the employee or employer making a mistake on a form, Gilman said. But, she added, “a mistake is not intentional fraud.”

In October of 2013, MiDAS began to flag people for fraud. Soon after, lawyers across the state were deluged with calls from people who were bewildered over their alleged fraud charges. Those who couldn’t afford a lawyer faced another hurdle: At the time, Michigan did not extend the right to free legal representation to those charged unemployment fraud. (The state extended this right through legislation in 2017.) Some turned to nonprofits, including the Unemployment Insurance Clinic at the University of Michigan Law School (re-named the Workers’ Rights Clinic in 2019) and the Maurice and Jane Sugar Law Center for Economic and Social Justice, a nonprofit legal advocacy organization in Detroit.

Anthony Paris, an attorney at the Sugar Law Center, told Undark that he and his colleagues assisted hundreds of clients who were accused of fraud between 2013 and 2015 — including Colvin. Over time, the legal team pieced together an understanding of the source of the surge of fraud charges: The new computer system had searched the unemployment database going back six years and flagged people for fraud based on error-prone rules.

One rule led to the agency to incorrectly accuse people of working while claiming unemployment benefits. Here, the system assumed, as described in a federal class action lawsuit filed in 2015 by Sugar Law Center and others, that the reported income from a part of the year was actually earned over a longer period. For example, a plaintiff named Kevin Grifka had reported $9,407.13 in earnings in 2015 before he was laid off in early February of that year and claimed unemployment benefits. The agency later claimed that he had made $723.62 each week throughout the full first quarter of the year — including the period when he said he was unemployed. As the lawsuit describes, this was based on dividing his income before being laid off by the 13 weeks of the whole quarter, and the same erroneous calculation was used to charge other plaintiffs.

The system also automatically accused people of intentional fraud when their story didn’t match that of their employer. Rather than assign a staff member to investigate discrepancies between what the employer and employee reported, Paris said, the system was programmed “to automatically assume that the employer was right.”

This is what led to Colvin’s fraud charge, according to court documents reviewed by Undark. Colvin’s employer reported that she had quit. Colvin said that her employer had told her she was suspended from work due to an issue reported at a house that was cleaned by her and another employee. Colvin never heard back and assumed she was laid off. Late in 2019, when Paris represented Colvin at a court hearing, her employer was called in to testify. The employer acknowledged she’d based her assumption that Colvin had quit on second-hand accounts from two other workers.

Colvin’s case highlighted another problem with MiDAS: It was designed with little attention to the right to due process. It’s a common problem in automated systems, said Jason Schultz, a law professor at New York University and a legal and policy researcher for the school’s AI Now Institute. “Even though the systems claim to notify people, they typically only notify them of the end result,” he added. “They don’t usually give them any information about how to actually understand what happened, why a decision was made, what the evidence is against them, what the rationale was, what the criteria were, and how to fix things if they’re wrong.”

Although MiDAS had several steps for notification, the forms were confusing, leading some innocent people to self-incriminate, according to Steve Gray — then director of the University of Michigan’s clinic — who described the problem in a co-authored letter to the Department of Labor. Moreover, many people never received the messages. The first one, the questionnaire, appeared in an online account that most people only checked when they were receiving benefits. And by the time the second notification by letter came around, many people had moved to a new address, according to a 2016 report from Michigan’s auditor general.

Brian Russell, an electrician from Zealand, Michigan, only learned about his alleged fraud after the state took $11,000 from his 2015 tax refund. He visited a state unemployment agency office and was astounded to learn that they would take even more: “They were charging me $22,000, and I had no idea what was going on.”

Russell said he tried everything he could think of to figure out why he was being charged — he visited the nearest unemployment office and called the agency “probably hundreds of times,” but the phone system was overloaded. He’d wait for hours on hold. (The state auditor’s report found that of the over 260,000 calls made to the line during business hours in a one month period in 2014, about 90 percent went unanswered.) Once Russell finally got a person on the line, he said he was told he’d missed the 30-day window to appeal.

Russell finally got representation from the University of Michigan’s law clinic, which appealed his case to an administrative law judge. A judge dismissed Russell’s charge and the agency refunded most of the money. (Russell said he is still owed about $1,500.) But in the meantime, he said he had to declare bankruptcy, which hit his credit score. And because he didn’t have the money for basic needs, he had to forgo some of his diabetes treatments and move into a friend’s basement.

While Michigan is a striking case of an automated system going wrong, it’s not the only area in which governments are using artificial intelligence systems for decision-making. Such systems are used in criminal justice, policing, child protective services, the allocation health care benefits, teacher evaluations, and more. In many cases, governments are hiring private companies to build these systems, said Pasquale, and since the companies want to protect their intellectual property, they sometimes hide details of how the products work. “The trade secret protection is a real problem, because you can’t even understand what the problems are,” he said.

Over the past few years, policymakers, academics, and advocates — including at organizations such as the AI Now Institute at NYU and Georgetown Law’s Center on Privacy and Technology — have explored different ways that governments could build better, more accountable automated systems.

Agencies also need to understand the limitations of a particular system before they implement it, said Julia Stoyanovich, an assistant professor of computer science at NYU. “My belief is that folks in government just think that AI is magic somehow,” she said, which can lead to big problems when the automated systems don’t run as smoothly in reality. Schultz agreed, adding that when government employees don’t have the background or resources to evaluate claims made by private companies “they’ll just get sold snake oil.”

Advocates and researchers are also pushing for governments to solicit guidance before implementing a new system, both from experts and from people who will be targeted by the new tools. In 2018, the AI Now Institute published a framework for this process, which Schultz co-authored. The idea is that governments need to think through steps for algorithms before they deploy them, Schultz said, asking questions like: “Does this system actually do what it says it’s going to do? Is it going to impact society in a way that actually helps and doesn’t hurt?” The authors also suggested that the assessment should be published and open for public comment.

Another model for accountability is designating an oversight body to audit algorithms. In early 2020, attorneys in the Michigan class action lawsuits called for the creation of a task force to oversee all algorithms and automated systems implemented by the state government. Other states and cities have formed similar task forces. Stoyanovich, who served on one formed in New York City, said she thought it was an important step. But it was also widely criticized — researchers from the AI Now Institute and other organizations, for instance, critiqued the effort for failing to adequately involve the wider community. And while oversight bodies could be important, Pasquale said, they need to have “real teeth” in order to yield meaningful enforcement.

But one of the biggest questions is whether and when to use algorithms to begin with — particularly for tools that could quickly erode privacy and civil liberties such as facial recognition. “I don’t think any government has to adopt any of these systems,” Schultz said. “I think spending millions of dollars on an unproven system that has no accountability and no way of ensuring it works is a really, really bad idea when it’s not required.”

In 2016 — in the midst of a flood of negative media attention — Michigan congressman Sander Levin pushed the agency to conduct an internal audit of the approximately 60,000 fraud charges in the prior two years. The agency responded with a partial audit, reviewing 22,000 of the MiDAS fraud charges and determining that nearly all were wrong. (The agency also reviewed another set of fraud charges made with some level of human review; while the error rate was still high at 44 percent, the automated system had more than twice that rate.)

By 2017, as part of a settlement of a class action lawsuit, the agency agreed it wouldn’t use the automated system without human review (and clarified that it actually stopped the practice in late 2015). The agency also agreed to review and overturn the remaining erroneous charges that it had issued between 2013 and 2015, later reporting that it had reversed about two-thirds of the fraud determinations and had repaid $21 million.

Also in 2017, state legislators passed a law to prevent such a disaster from happening again through improvements in fraud charge notifications and reduced fines. And in 2019, in a move that several attorneys described to Undark as a step in a positive direction, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer appointed Gray, formerly the head of the unemployment insurance law clinic at the University of Michigan Law School, as director of the agency.

In available court documents, which include depositions of agency staff and the three companies, none of the people involved in making or approving the automated system admit responsibility (as plaintiffs’ lawyers confirmed). While the ongoing cases should eventually reveal more details — including discovery involving more than a million documents such as internal agency emails — the suit will take a long time to work its way through the courts, Paris said.

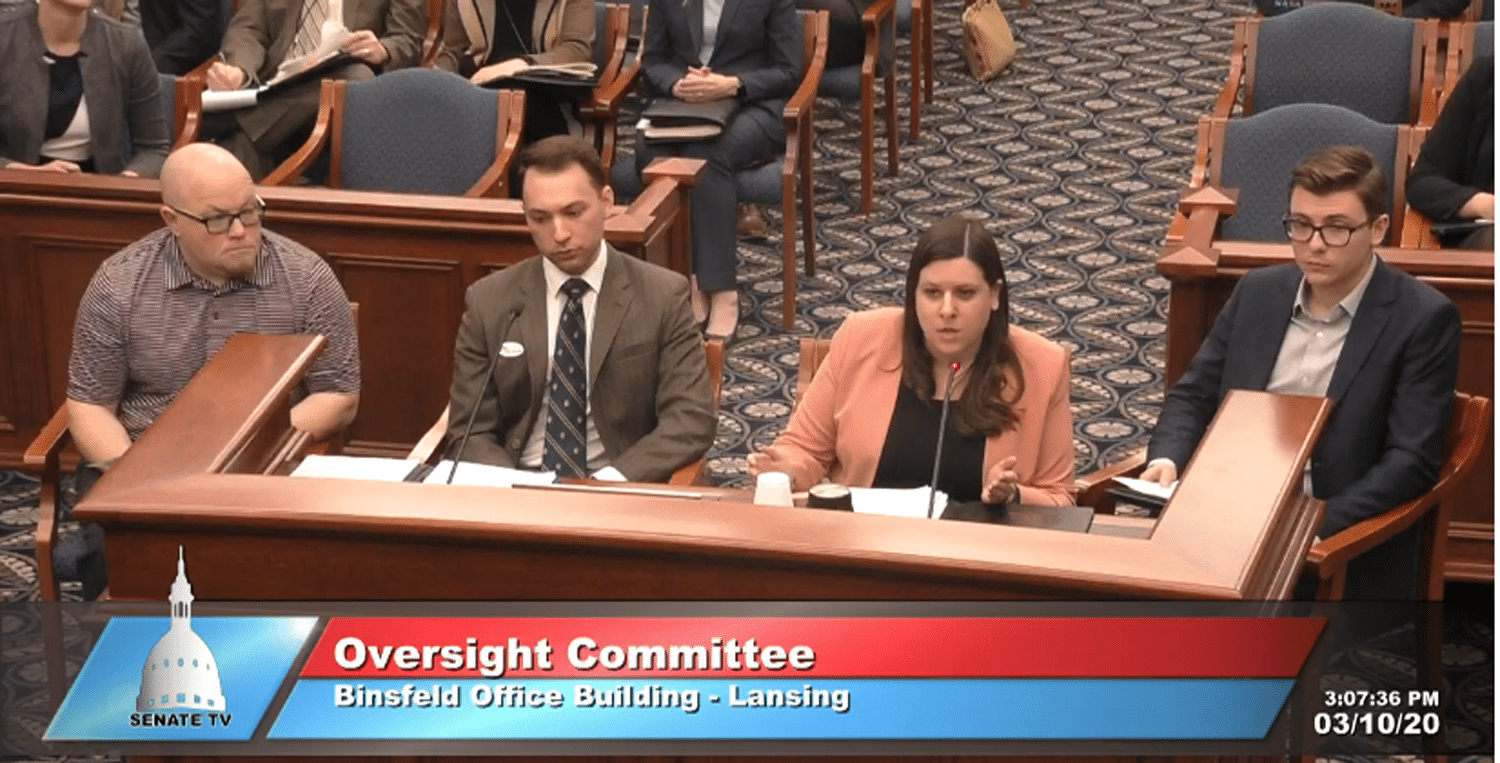

Meanwhile, for some people who were falsely accused of fraud, the struggle continues. In addition to the class action lawsuits, in March 2020, the current director of the University of Michigan Law School’s Workers’ Rights Clinic testified to the state Senate Oversight Committee that they believe close to 20,000 of those charged by MiDAS are still being actively pursued and having their wages garnished.

For Colvin, it wasn’t until early 2020, nearly six years after she had been charged, that an administrative judge finally dismissed her case. In the middle of that stretch, in 2017, Colvin completed her bachelor’s degree in criminal justice, adding to a previous associate’s degree in forensic photography, and applied for a job with a county sheriff’s office. She soon got a call letting her know that she wouldn’t be hired because of the fraud charge and her outstanding debt to the state.

Today, Colvin said she is working as a security guard to support herself and her daughter. She is 32, and wonders if it was a waste of time to get two degrees in criminal justice.

“I can’t get the job I wanted,” she said, “because they suggested that I was a criminal.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

It’s not ALL truth. How did frauds get their money but other millions of honest people didn’t receive money. Government is pushing you to find work until your job recalls because it’s their righteous workers’ way. Humanity?!. Use a different computer or phone because they’ve blocked/ hacked your original honest device to prohibit your call. Lump sum Money should be given to the people who suffer. In addition to the fraudulent halted unemployment payments. Everything and everyone has a judgement. This is only the beginning.😜😂🙄

The Michigan UIA system is so inferior. Or, is it the fault of the people who are employed at UIA that are flawed?? I have had to verify my identification (submitted certified docs) now FOUR TIMES since filing back in March. My unemployment benefits payments have been stopped once again, because I received yet another letter/email stating that the system is identifying my account as possibly fraudulent. This is inexcusable, and I have no doubt that this is happening to others who are in need of unemployment compensation. Someone needs to get into the programming for this system and fix this! People like me are suffering financially due to this problem. I am running out of funds fast!

So, wheres the proof that fraud is happening?? Just that our benefits are frozen, that the unemployment office just hangs up on us, the live chat ends before 2 words are typed or because they say so???!! Wtf!!! Eviction notice, utility shut offs, vehicle repo, wtf is next!!

The U.S. IRS has a similar algorithm which banks, etc., must use for tracking “structuring” (a.k.a. “smurfing”) international cash transfers. We were our own general contractor, building our house in Costa Rica. A couple of times a month, we’d have to pay for materials and worker’s salaries and it worked out to many tranasfers of $7000 to $9500. About the 4th transfer over $9000 and our U.S. financial company blocked our account. The computer said we were “smurfing” and probably money launderers. Receipts? Photos? Detailed accountant’s spreadsheets? Nope. Not interested. We had to be bad guys because the computer said so. We had to change from the investment bank to a plain consumer bank, but by that time we were so near to completion we apparently weren’t triggering the consumer bank’s software.