Are We Offloading Critical Thinking to Chatbots?

In January, researchers at Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University posted a study online on how artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT affect critical thinking. They wanted to know how knowledge workers — people who rely on their intellectual skills for their jobs — were interacting with the tools. And through detailed surveys, their findings suggest that the higher the confidence those workers felt in generative AI, the less they themselves relied on critical thinking.

As one of the test subjects noted in the study, “I use AI to save time and don’t have much room to ponder over the result.”

The Microsoft paper is part of a nascent but growing body of research: Over the past two years, as more people have experimented with generative AI tools like ChatGPT at work and at school, cognitive scientists and computer scientists — many of them employed by the very companies that make these AI tools, as well as independent academics — have tried to tease out the effects of these products on how humans think.

Research from major tech companies on their own products often involves promoting them in some way. And indeed, some of the new studies emphasize new opportunities and use cases for generative AI tools. But the research also points to significant potential drawbacks, including hindering developing skills and a general overreliance on the tools. Researchers also suggest that users are putting too much trust in AI chatbots, which often provide inaccurate information. With such findings coming from the tech industry itself, some experts say, it may signal that major Silicon Valley companies are seriously considering potential adverse effects of their own AI on human cognition, at a time when there’s little government regulation.

“I think across all the papers we’ve been looking at, it does show that there’s less effortful cognitive processes,” said Briana Vecchione, a technical researcher at Data & Society, a nonprofit research organization in New York. Vecchione has been studying people’s interactions with the chatbots like ChatGPT and Claude, the latter made by the company Anthropic, and has observed a range of concerns among her study’s participants, including dependence and overreliance. Vecchione notes that some people take chatbot output at face value, without critically considering the text the algorithms produce. In some fields, the error risks could have significant consequences, experts say — for instance if those chatbots are used in medicine or health contexts.

“I think across all the papers we’ve been looking at, it does show that there’s less effortful cognitive processes.”

Every technological development naturally comes with both benefits and risks, from word processors to rocket launchers to the internet. But experts like Vecchione and Viktor Kewenig, a cognitive neuroscientist at Microsoft Research Cambridge in the United Kingdom, say that the advent of the technology that girds today’s AI products — large language models, or LLMs — could become something different. Unlike other modern computer-based inventions, such as automation and robotics inside factories, internet search engines, and GPS-powered maps on devices in our pockets, AI chatbots often sound like a thinking person, even if they’re not.

As such, the tools could present new, unforeseen challenges. Compared to older technologies, AI chatbots “are different in that they are a thinking partner to a certain extent, where you’re not just offloading some memory, like memory about dates, to Google,” said Kewenig, who’s not involved in the Microsoft study but collaborates with some of its co-authors. “You are in fact offloading many other critical faculties as well, such as critical thinking.”

Large language models are powerful, or appear powerful, because of the vast information on which they’re based. Such models are trained on colossal amounts of digital data — which may have involved violating copyrights — and in response to a user’s prompt, they’re able to generate new material, unlike older AI products like Siri or Alexa, which simply regurgitate what’s already published online.

As a result, some people may be more likely to trust the chatbot’s output, Kewenig said: “Anthropomorphizing might sometimes be tricky, or dangerous even. You might think the model has a certain thinking process that it actually doesn’t.”

AI chatbots have been observed to occasionally produce flawed outputs, such as recommending to eat rocks and put glue on pizza. Such inaccurate and absurd AI outputs have become widely known as hallucinations, and they arise because the LLMs powering the chatbots are trained on a broad array of websites and digital content. Because of the models’ complexity and the reams of data fed into them, they have significant hallucination rates: 33 percent in the case of OpenAI’s o3 model and higher in its successor, according to a technical report the company released in April.

“Anthropomorphizing might sometimes be tricky, or dangerous even. You might think the model has a certain thinking process that it actually doesn’t.”

In the Microsoft study, which was published in proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in April, the authors characterized critical thinking with a widely used framework known as Bloom’s taxonomy, which distinguishes types of cognitive activities from simpler to more complex ones, including knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. In general, for these workers, the researchers found that using chatbots tends to change the nature of the effort people invest in critical thinking. It shifts from information gathering to information verification, from problem-solving to incorporating the AI’s output, and it shifts other types of higher-level thinking to merely stewarding the AI, steering the chatbot with their prompts and assessing whether the response is sufficient for their work.

The researchers surveyed 319 knowledge workers in the U.K., U.S., Canada, and other countries in a range of occupations, from computer scientists and mathematicians to jobs related to design and business. The participants were first introduced to concepts and examples of critical thinking in the context of AI use, such as “checking the tone of generated emails, verifying the accuracy of code snippets, and assessing potential biases in data insights.” Then, the participants responded to a list of multiple-choice and free-response questions, providing 936 examples of work-related AI usage, mostly involving generating ideas and finding information, while assessing their own critical thinking.

According to the paper, the connections to critical thinking were nuanced. The paper noted, for instance, that higher confidence in generative AI is associated with less critical thinking, but that among respondents with more self-confidence in their own abilities, there was an increase in critical thinking.

Vecchione and other independent experts say that this study and others like it are an important step toward understanding potential impacts of using AI chatbots. Vecchione’s assessment is that the Microsoft paper does seem to show that generative AI use is associated with less effortful cognitive processes. “One thing that I think that is interesting about knowledge workers in particular is the fact that there are these corporate demands to produce,” she added. “And so sometimes, you could understand how people would forego more critical engagement just because they might have a deadline.”

Microsoft declined Undark’s interview requests, via the public relations firm it works with, but Lev Tankelevitch, a senior researcher with Microsoft Research and a study co-author, did respond with a statement, which noted in part that the research “found that when people view a task as low-stakes, they may not review AI outputs as critically.” He added that, “All the research underway to understand AI’s impact on cognition is essential to helping us design tools that promote critical thinking.”

Other new research outside Microsoft presents related concerns and risks. For example, in March, an IBM study, which has not yet been peer reviewed, initially surveyed 216 knowledge workers at a large international technology company in 2023, followed by a second survey the next year with 107 similarly recruited participants. These surveys revealed an increased AI job-related usage — 35 percent, compared to 25 percent in the first survey — as well as emerging concerns among some of them about trust, both in the chatbots themselves and in co-workers who use them. “I found a lot of people talking about using these generative AI systems as assistants, or interns,” said Michelle Brachman, a researcher of human-centered AI at IBM and lead author of the study. She gleaned other insights as well, while interacting with the respondents. “A lot of people did say they were worried about their ability to maintain their skills, because there’s a risk you end up relying on these systems.”

People need to critically evaluate how they interact with AI systems and put “appropriate trust” in them, she added, but they don’t always do that.

“Sometimes, you could understand how people would forego more critical engagement just because they might have a deadline.”

And some research suggests that chatbot users may misjudge the usefulness of AI tools. Researchers at the nonprofit Model Evaluation & Threat Research recently published a preprint in which they conducted a small randomized controlled trial of software developers who completed work tasks with and without AI tools. Before getting started, the coders predicted that AI use would speed up their work by 24 percent, on average. But those productivity gains were not realized; instead, their completion time increased by 19 percent. The researchers declined Undark’s interview requests. In their paper, they attributed that slowdown to multiple factors, including low AI reliability, the complexity of the tasks, and overoptimism about AI usefulness, even among people who had spent many hours using the tools.

Of the findings, Alex Hanna, a sociologist, research director at Distributed AI Research Institute, and co-author of “The AI Con,” said: “It’s very funny and a little sad.”

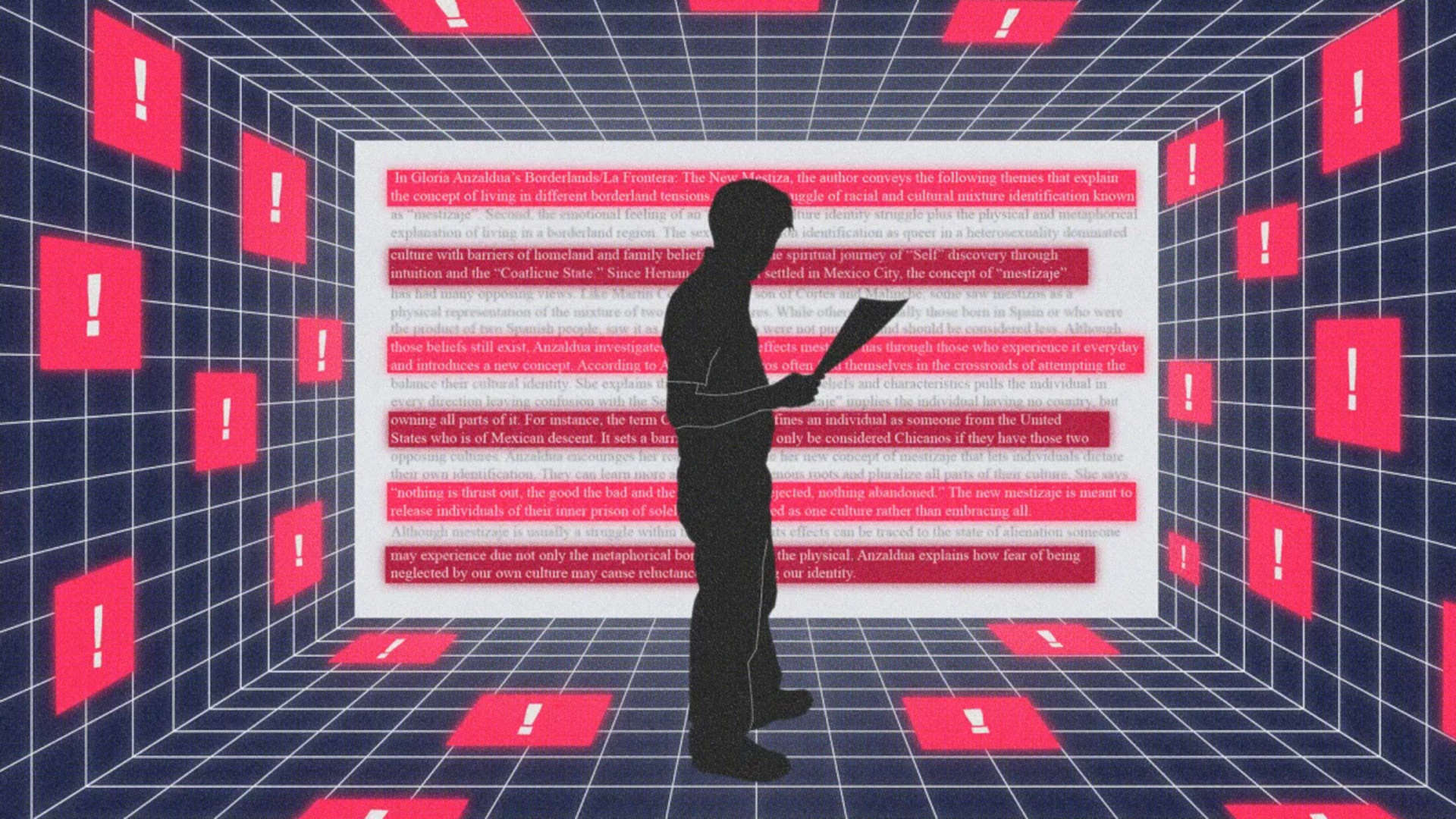

In addition to looking into knowledge workers, much of the current AI-related research focuses on students. And if the connections between AI use and critical thinking prove true, some of these studies appear to confirm early concerns regarding the effects of the technology on education. In a 2024 Pew survey, for instance, 35 percent of U.S. high school teachers suggested AI in education can do more harm than good.

In April, researchers at Anthropic released an education report, analyzing one million anonymized university student conversations with its chatbot Claude. Based on the researchers’ study of those conversations, they find that the chatbot was primarily used for higher-order cognitive tasks, like “creating” and “analyzing.” The report also briefly notes concerns about critical thinking, cheating, and academic integrity. (Anthropic declined Undark’s interview requests.)

Then in June, MIT research scientist Nataliya Kosmyna and her colleagues released a paper, which hasn’t yet gone through peer review, studying the brain patterns of 54 college students and other young adults in the greater Boston area as they wrote an essay.

The MIT team noticed significant differences in the brain patterns of the participants’ brains — in areas that are not associated as a measure of intelligence, Kosmyna emphasized. Participants who only used LLMs to help with their task had lower memory recall; their essays had more homogeneity within each topic; and more than 15 percent also reported feeling like they had no or partial ownership over the essays they produced, while 83 percent had trouble quoting from the essays they had written just minutes ago.

“It does paint a rather dire picture,” said Kosmyna, lead author of the study and a visiting research faculty at Google.

The MIT findings appear to be consistent with a paper published in December, which involved 117 university students whose second language was English, who performed writing and revising tasks and responded to questions. The researchers found signs of what they described as “metacognitive laziness” about thinking among learners in the group using ChatGPT 4. That means some appeared to be becoming dependent on that AI assistance and offloading some of their higher-level thinking, such as goal-setting and self-evaluation, to the AI tools, said Yizhou Fan, the lead author.

People need to critically evaluate how they interact with AI systems and put “appropriate trust” in them.

The problem is that some learners, and some educators as well, don’t really distinguish between learning and performance, as it’s usually the latter that is judged for high or low marks, said Dragan Gašević, a computer scientist and professor at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia and a colleague of Fan’s. “Generative AI helps us enhance our performance,” in a way like doping, he said. “While learning itself requires much deeper engagement and experiencing hurdles.”

All this research literature comes with limitations. Many of the studies have fairly small sample sizes, focus on very specific tasks, and the participants might not be representative of the broader population, as they’re typically selected by age, education level, or within a narrow geographic area, in the case of Kosmyna’s research. Another limitation is the short time span of the studies. Expanding the scope could fill in some gaps, Vecchione said: “I’d be curious to see across different demographics over longer periods of time.”

Furthermore, critical thinking and cognitive processes are notoriously complex, and research methods like EEGs and self-reported surveys can’t necessarily capture all of the relevant nuances.

Some of these studies have other caveats as well. The potential cognitive impacts aren’t observed so much among people with more experience with generative AI and with more prior experience in the task for which they want assistance. The Microsoft study spotted such a trend, for example, but with weaker statistical significance than the negative effects on critical thinking.

Despite the limitations, the studies are still cause for concern, Vecchione said. “It’s so preliminary, but I’m not surprised by these findings,” she added. “They’re reflective of what we’ve been seeing empirically.”

Companies often hype their products while trying to sell them, and critics say the AI industry is no different. The Microsoft research, for instance has a particular spin: The authors suggest that it’s helpful that generative AI tools could “decrease knowledge workers’ cognitive load by automating a significant portion of their tasks,” because it could free them up to do other types of tasks at work.

Critics have noted that AI companies have excessively promoted their technology since its inception, and that continues: A new study published by design scholars documents how companies including Google, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, and Adobe “impose AI use in both personal and professional contexts.”

Some researchers, including Kosmyna at MIT, argue that AI companies have also aggressively pushed the use of LLMs in educational contexts. Indeed, at an event in March, Leah Belsky, OpenAI’s VP of education, said the company wants to “enable every student and teacher globally to access AI” and advocates for “AI-native universities.” The California State University system, the University of Maryland, and other schools have already begun incorporating generative AI into students’ school experiences, such as by making ChatGPT easily accessible, and Duke University recently introduced a DukeGPT platform. Google and xAI have begun promoting their AI services to students as well.

The potential cognitive impacts aren’t observed so much among people with more experience with generative AI and with more prior experience in the task for which they want assistance.

All this hype and promotion likely stems from the desire for larger-scale adoption of AI, while OpenAI and many other entities investing in AI remain unprofitable, said Hanna. AI investors and analysts have begun speculating that the industry could be in the midst of a bubble. At the same time, Hanna argues, the hype is useful for business managers who want to engage in massive layoffs, but not because the LLMs are actually replacing workers somehow.

Hanna believes the preliminary research about generative AI and critical thinking, such as the work from Microsoft, is worth taking seriously. “Many people, despite knowing how it all works, still get very taken with the technology and attribute to it a lot more than what it actually is, either imputing some notion of intelligence or understanding,” she said. Some people might benefit if they have in-depth AI literacy and really know what’s inside the black box, she suggests. However, she added, “that’s not most people, and that’s not what’s being advertised by companies. They benefit from having this veneer of magicalness.”

I would also say that one of the limitations of these studies is no benchmarking with student homogeneity and recall on essays they write last-minute until 4am, or in other situations not conducive to actual learning.

Key typo seems to be present when you cite 19% change in completion time vs expected 24% change. (https://metr.org/blog/2025-07-10-early-2025-ai-experienced-os-dev-study/) You use word “increase” when study you are citing says “decrease.” Completion time fell instead of rose less than expected.

Hi Matthew,

The pre-print says: “Surprisingly, we find that allowing AI actually increases completion time by 19%— developers are slower when using AI tooling.”

Best,

Jane

This insightful piece highlights a crucial blind spot in AI adoption—our tendency to anthropomorphize chatbots, potentially compromising critical thinking. The blend of expert analysis and relatable examples effectively underscores the need for caution.