Humans have turned to nature for solace and revival for centuries, without knowing exactly why it makes us feel better. “It is not so much for its beauty that the forest makes a claim upon men’s hearts, as for that subtle something, that quality of the air, that emanation from the old trees, that so wonderfully changes and renews a weary spirit,” Robert Louis Stevenson wrote in the mid-1870s. But what is that subtle something, and why does it affect us so profoundly?

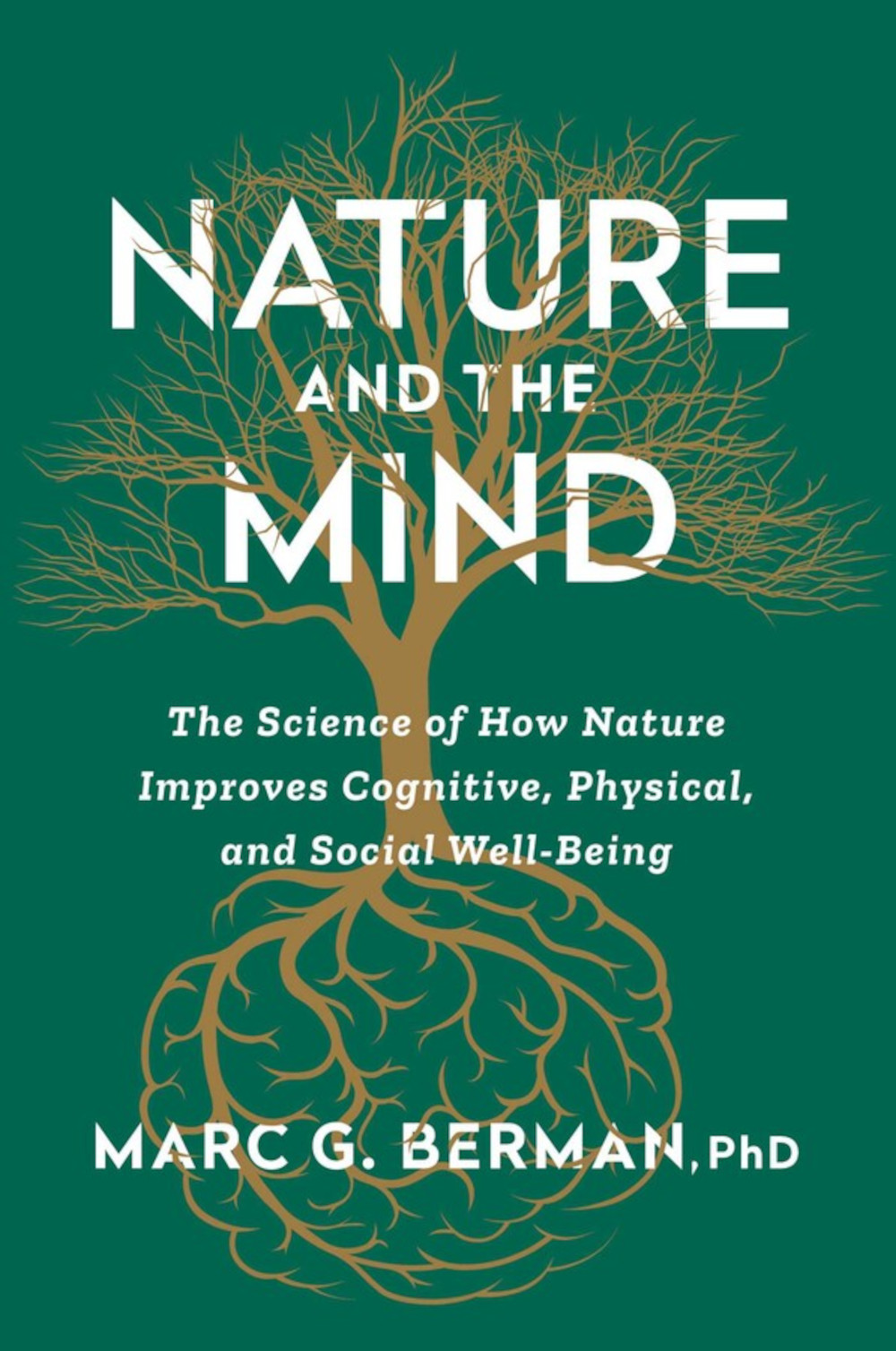

BOOK REVIEW — “Nature and the Mind: The Science of How Nature Improves Cognitive, Physical, and Social Well-Being,’’ by Marc Berman (S&S/Simon Element, 336 pages).

In “Nature and the Mind: The Science of How Nature Improves Cognitive, Physical, and Social Well-Being,” neuroscientist Marc Berman brings the data, drawing on his own research and work by other scientists into the psychological and physiological ways in which spending time in natural environments improves human well-being. He starts by recounting a 2008 study that he conducted as a graduate student with his advisers at the University of Michigan.

The researchers gave subjects challenging memory tests, including one called the backward digit span task, in which they would hear a list of up to nine digits and then try to repeat them in reverse order. After completing the tests, the subjects took a 2.8 mile walk either through downtown Ann Arbor or in the university’s leafy arboretum, and repeated the tests. The urban walk did not measurably affect participants’ scores, but walking in the arboretum improved their performance on memory- and attention-related tasks by 20 percent. Looking at pictures of either natural or urban scenes produced similar, although somewhat weaker, results.

“Other studies had asked people how they felt after time in nature, but none had ever quantified nature’s impact on our cognition using objective measures,” Berman writes.

In Berman’s view, attention is a central element of cognition. He sees directed attention — the ability to choose what to focus on and filter out what’s less important — as a critical human capability. “Instead of knee-jerk reactions we may regret, directed attention allows us to pause, consider our intentions, and respond to people and experiences with measure,” he explains. “It keeps our flashes of anger from becoming violent behavior” and “keeps us on task when that’s what we want.”

“Other studies had asked people how they felt after time in nature, but none had ever quantified nature’s impact on our cognition using objective measures.”

And modern society, with its plethora of distractions — especially the digital economy and social media — has made attention “the World’s Most Endangered Resource,” in the words of political commentator Chris Hayes, author of the recent book “The Siren’s Call.” Businesses that want our attention — and the user data that comes with it — are churning out web-based products and services designed to keep us online and engaged, and, in some cases, away from their competitors.

For Berman, the founder and director of the Environmental Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Chicago, this trend is worrisome because directed attention isn’t just a vital ability. It’s also a limited one, and can easily become depleted as we multitask, juggle work and family needs, and try to tune out tech-based noise. “Today, we’re pushing our directed attention to a breaking point,” he warns. “We’re getting distracted when it’s not necessary or adaptive, and our very ability to maintain our important relationships and live meaningful lives is at risk.”

Berman sees hope in a concept called Attention Restoration Theory, developed by University of Michigan psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan, that posits nature as an answer to directed attention depletion. The Kaplans saw natural stimuli — think of leaves rustling on tree branches, or clouds drifting across the sky — as fundamentally different from manmade signals, like cell phone alerts or billboards. Nature’s sights and sounds engage a kind of thinking the Kaplans called “soft fascination” that doesn’t take up all of an observer’s attention. When you sit next to a flowing stream, you can listen to the water splashing and also let your mind wander more widely. That experience, the Kaplans hypothesized, offered an opportunity to replenish our directed attention.

The 2008 “Walk in the Park” study was an early empirical test of attention restoration theory. Its results were encouraging, but raised more questions for Berman: How much restorative power did time in nature have? How did it work, and how could it be applied?

In Berman’s view, attention is a central element of cognition. He sees directed attention — the ability to choose what to focus on and filter out what’s less important — as a critical human capability.

In a follow-up study, Berman and colleagues recruited participants who were experiencing clinical depression and had them carry out the same memory tasks, followed by the same walks. Before the walks, the researchers prompted their subjects to think about something negative that was bothering them, to put them into the mode of repetitive negative rumination that characterizes depression and saps directed attention. Participants who took walks in nature showed even greater cognitive gains than those in the original study.

“It felt like discovering a fifty-minute miracle — a therapy with no known side effects that’s readily available and can improve our cognitive functioning at zero cost,” Berman writes. The results echoed findings by scientists at the University of Illinois who discovered that when children with ADHD spent time in green outdoor settings, they showed fewer attention-related symptoms afterward compared to others who spent time in human-made spaces. In one study, children with ADHD showed attention performance improvements after a walk in a park that were comparable to the effects from a dose of Ritalin.

Another notable aspect of Berman’s findings was that people didn’t have to like nature to benefit from it. Participants in the walking studies didn’t always experience mood benefits, but they showed clear attention-related improvements. “Good medicine doesn’t always taste sweet,” Berman observes.

Another area of Berman’s research examined which features of nature provided these benefits. Through several studies that asked subjects to rate photos of natural and built settings, he and his colleagues found four key qualities that people considered “natural”: abundant curved edges, such as the bends of rivers; an absence of straight lines, such as highways; green and blue hues; and fractals — branching patterns that repeat at multiple scales. Fractals can be generated mathematically, but they also occur throughout nature, from tree branches to many snowflake designs.

“Natural curves and natural fractals are all softly fascinating because they can balance complexity and predictability,” Berman writes. “They’re not so complex that they’re overwhelming, but not so predictable that they’re boring. Instead, they live in a kind of active equilibrium, like a churning waterfall or a burning campfire — things humans tend to find particularly softly fascinating.”

Using artificial neural networks — machine learning programs that may make decisions in ways similar to human brains — Berman and a doctoral student found that scenes with more natural elements were likely to be less memorable to humans than urban scenes. This suggests that it takes less directed attention to process natural stimuli. When we look at something like a tree with a huge mass of leaves, we don’t zero in on each individual leaf and analyze its features. Instead, we throw away a lot of the repeated elements and focus on the key features, such as the tree’s overall shape, mass and colors. This leaves us with more brainpower for other tasks.

Participants in the walking studies didn’t always experience mood benefits, but they showed clear attention-related improvements. “Good medicine doesn’t always taste sweet,” Berman observes.

These observations have implications for design — not just for those of us who can easily add plants and natural materials to our homes, but on a larger scale. One ongoing focus in Berman’s environmental neuroscience lab is combining brain science with urban planning to improve the designs of cities and towns. He argues that access to nature should be seen as a human right, rather than a nice perk, and that it’s especially important to provide more green space in cities, where the majority of the world’s population lives.

“If we don’t investigate the increases in individual and societal health that nature can offer us — if we just go on a gut sense that nature is good — then only the wealthiest among us will continue to have consistent access to the ways nature can keep us healthy and safe,” he asserts. “Meanwhile, poor and marginalized populations will continue to lack access, and worse, be told (or shown) that nature is not for them.”

While Berman is clearly frustrated by our tendency to underestimate how much we need nature, there is a strongly optimistic thread running through his highly readable and jargon-free account. Humans, he reminds us, “are not who we are by individual factors alone — we are who we are because of our environment and how individual factors interact with environmental factors (such as nature) to shape us.”

“And science,” he concludes, “shows that cultivating access to green space changes minds in ways beyond our wildest expectations.”

Jennifer Weeks (@jenniferweeks83.bsky.social) is a Boston-based journalist and former senior editor at The Conversation U.S. Her articles have appeared in Audubon, Slate, The Boston Globe Magazine and many other outlets.