Within the next week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is expected to make a decision about whether to approve the psychedelic MDMA (midomafetamine) for use in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder in conjunction with psychological intervention. In the last decade, psychedelics have moved from the fringes of medicine to the mainstream, drawing attention from the media, investors, and the general public. But in a June meeting, an FDA advisory committee declined to recommend MDMA’s approval. If the FDA heeds its advisers, as it usually does, the agency’s decision could slow down the timelines of getting psychedelics to market as other potential treatments, including psilocybin and ketamine, are likely to face similar regulatory challenges.

During the June meeting, FDA advisers raised a range of issues related to the quality of evidence. To move psychedelics forward, manufacturers may need to follow the advice the FDA has previously given, in addition to considerations provided in FDA draft guidance and advisory committee minutes, particularly on how to structure clinical trials that address FDA concerns about methodological biases and missing data.

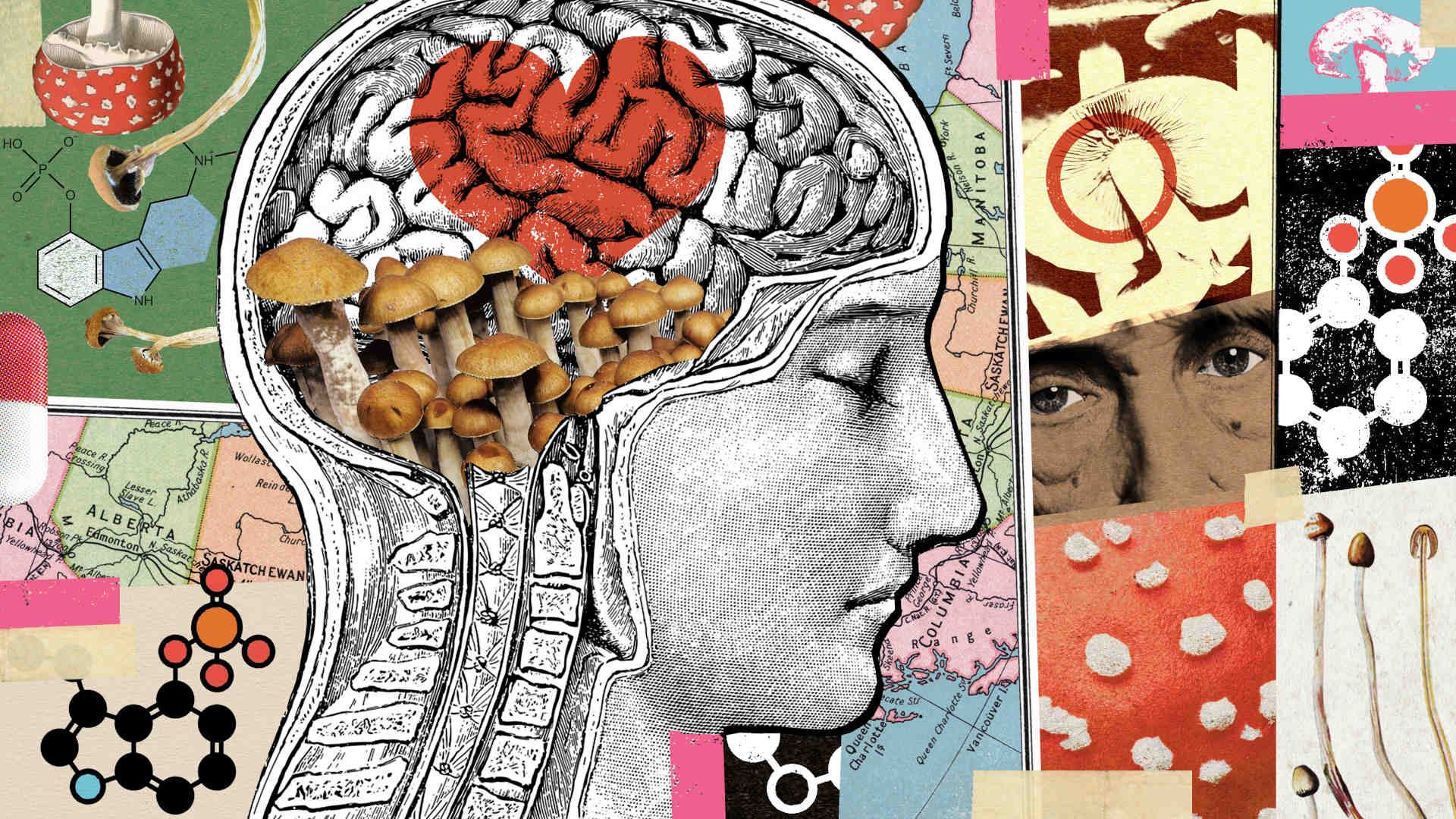

Psychedelic-assisted treatment involves the use of psychedelic substances alongside traditional talk therapy for a wide range of mental health issues, including PTSD, treatment-resistant depression, severe anxiety, and substance abuse. Most psychedelics are Schedule I substances with no currently accepted use in medicine. There appears to be a broad consensus, however, that psychedelics are worthy of research in disease areas with a significant amount of unmet need, in particular, PTSD and treatment-resistant depression.

PTSD is a complex psychiatric disorder which can be associated with substantial disability and poor quality of life that occurs in people who have experienced or witnessed one or more traumatic events. In the U.S., somewhere between 9 and 13 million people suffer from PTSD annually. Treatment-resistant depression affects approximately 30 percent of patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder. The National Institute of Mental Health estimates that 21 million adults had at least one episode of major depression in 2021.

There appears to be a broad consensus that psychedelics are worthy of research in disease areas with a significant amount of unmet need, in particular, PTSD and treatment-resistant depression.

The FDA first granted breakthrough therapy status to MDMA and psilocybin, another psychedelic substance being studied for its potential mental health applications, in 2017 and 2018, respectively, which helped to expedite their development and review. The designation recognizes a drug’s therapeutic potential when that medication is intended to treat a serious condition and when early clinical evidence suggests the drug may be more effective than currently available treatments.

Excitement in the field gathered steam when Nature Medicine published findings in 2021 from a study on MDMA, which showed that the drug combined with psychological counseling yielded symptomatic relief to patients with severe PTSD. Around the same time, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found psilocybin, a psychoactive ingredient in certain mushrooms, performed similarly to an antidepressant at treating major depressive disorder. (However, the study noted that “the absence of a placebo group in the trial limits conclusions about the effect of either agent alone.”) These results came on the heels of another important study, published in JAMA Psychiatry, which suggested “substantial, rapid, and enduring” antidepressant effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy among patients with the condition.

The Nature Medicine study was funded by the U.S. nonprofit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. In 2022, the organization announced that its for-profit drug developer, Lykos Therapeutics (known as MAPS Public Benefit Corporation at the time), had completed a second Phase 3 trial on MDMA as a treatment for PTSD. MAPS said the findings from the second Phase 3 trial — which tested the safety and efficacy of MDMA against a placebo — echoed positive results from the Nature Medicine paper. Subsequently, Lykos filed a New Drug Application in late 2023.

FDA expert panelists reviewed data from these two phase 3 trials, in which PTSD patients received three doses of MDMA or a placebo over a period of three months combined with sessions of psychotherapy.

In the Phase 3 studies, researchers found greater improvements in symptoms in those who were given the combination of MDMA and psychotherapy compared to those who only received psychotherapy. But FDA advisers raised a number of concerns about how the trials were conducted.

Ideally, in a clinical trial, neither the patient nor the therapist knows which patients are receiving the drug and which are not. But because MDMA, like other psychedelics, produces perceptual disturbances, many patients in the Lykos trials knew whether they received MDMA or a placebo. This raises the possibility that the trial results were influenced by expectancy bias: Those who received MDMA might have improved because they expected, or hoped, that the drug would help them. Conversely, those who received the placebo may have experienced a nocebo effect, which means worsening symptoms because they were aware they did not get active treatment.

FDA officials had suggested in 2016 that Lykos use an active compound for the control group to help mask whether participants had received MDMA. But the company pushed back. Ultimately, the trial went ahead in 2017 with an inactive placebo and with FDA’s backing.

Ideally, in a clinical trial, neither the patient nor the therapist knows which patients are receiving the drug and which are not.

Lykos also asked that its recommended psychotherapy be included in the approval procedure. But this made the trial design problematic for the committee. Because MDMA and psychotherapy were administered together, it’s hard to tell how much of the effect was due to MDMA and how much owed to psychotherapy. Moreover, the FDA does not regulate psychotherapy.

An additional problem cited by the committee is that Lykos didn’t collect all MDMA abuse-related adverse events in its Phase 3 studies, even though the FDA advised as far back as March 2017 that it should. (At the advisory committee meeting, the FDA announced that it was investigating allegations of data suppression and sexual misconduct in the clinical trials.)

Psilocybin contends with similar challenges.

Some studies of psilocybin have also failed to account for expectancy bias and how to untangle the possible effects of other antidepressants, as well as psychotherapy, used by subjects in trials.

In 2022, Nature Medicine published a paper in which the authors suggested an “antidepressant mechanism for psilocybin therapy,” or what some experts call a rewiring of the brain in which there’s an increase in connectivity between areas of the brain.

A vigorous debate ensued over the quality of the study design. In a blog post, Eiko Fried, an associate professor of clinical psychology at Leiden University in the Netherlands, remarked that to show a treatment “outperforms” another — in this case, psilocybin compared to an antidepressant — researchers must test for an interaction effect, which he said the authors failed to do. In other words, the researchers would need to look at whether the difference in change between the two treatment groups was large enough to be significant.

Indeed, prior to the blog post, Fried published a checklist to assess the quality of psychedelic research, writing it’s imperative to test for issues such as interaction effects and expectancy bias. He also called for greater sample sizes and more consistent reporting of adverse events.

Several Phase 3 trials have commenced for psilocybin-assisted therapy, including a Phase 3 program consisting of two pivotal trials being conducted by Compass Pathways, a mental health biotechnology company, and a similarly designed Phase 3 trial being carried out by the Usona Institute, a nonprofit medical research organization. It’s unknown whether the issues cited by Fried and others are adequately accounted for in the trial design.

If the FDA denies approval of Lykos’ MDMA-assisted therapy, the company could conduct revised studies and reapply. FDA draft guidance posted in June 2023 provides a potential framework on how to overcome expectancy bias and the nocebo effect by employing an active placebo which could be a substance that also has mind-altering effects but no expected therapeutic benefit. This was reiterated during a virtual public meeting, “Advancing Psychedelic Clinical Study Design,” organized by the Reagan-Udall Foundation for the FDA in the winter of 2024.

If the FDA denies approval of Lykos’ MDMA-assisted therapy, the company could conduct revised studies and reapply.

In the case of MDMA specifically, Lykos and other psychedelics companies could consider, for example, as one psychedelic clinical trials organization suggested, a study design to separate the efficacy of the psychedelic substance from the psychotherapy component and run four arms of the trial: psychedelic with psychotherapy, psychedelic alone, placebo with psychotherapy, and placebo alone.

No one who has a stake in the development of psychedelic drugs — including researchers, developers, and patients — wants the process to be delayed by regulatory setbacks. Accordingly, researchers must design trial protocols that properly account for potential harm to subjects, bias, functional blinding, and use of other treatments such as antidepressants and psychotherapy.